Carya Eral Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree Mycorrhizal Type Predicts Within‐Site Variability in the Storage And

Received: 6 December 2017 | Accepted: 8 February 2018 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14132 PRIMARY RESEARCH ARTICLE Tree mycorrhizal type predicts within-site variability in the storage and distribution of soil organic matter Matthew E. Craig1 | Benjamin L. Turner2 | Chao Liang3 | Keith Clay1 | Daniel J. Johnson4 | Richard P. Phillips1 1Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA Abstract 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Forest soils store large amounts of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), yet how predicted Balboa, Ancon, Panama shifts in forest composition will impact long-term C and N persistence remains 3Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Management, Institute of Applied Ecology, poorly understood. A recent hypothesis predicts that soils under trees associated Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang, with arbuscular mycorrhizas (AM) store less C than soils dominated by trees associ- China ated with ectomycorrhizas (ECM), due to slower decomposition in ECM-dominated 4Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, USA forests. However, an incipient hypothesis predicts that systems with rapid decom- position—e.g. most AM-dominated forests—enhance soil organic matter (SOM) sta- Correspondence Matthew E. Craig, Department of Biology, bilization by accelerating the production of microbial residues. To address these Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. contrasting predictions, we quantified soil C and N to 1 m depth across gradients of Email: [email protected] ECM-dominance in three temperate forests. By focusing on sites where AM- and Funding information ECM-plants co-occur, our analysis controls for climatic factors that covary with myc- Biological and Environmental Research, Grant/Award Number: DE-SC0016188; orrhizal dominance across broad scales. -

Erigenia : Journal of the Southern Illinois Native Plant Society

ERIGENIA THE LIBRARY OF THE DEC IS ba* Number 13 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 1994 ^:^;-:A-i.,-CS..;.iF/uGN SURVEY Conference Proceedings 26-27 September 1992 Journal of the Eastern Illinois University Illinois Native Plant Society Charleston Erigenia Number 13, June 1994 Editor: Elizabeth L. Shimp, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial St., Harrisburg, IL 62946 Copy Editor: Floyd A. Swink, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Publications Committee: John E. Ebinger, Botany Department, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920 Ken Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. 1 Box 495 A, Westville, IL 61883 Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 Lawrence R. Stritch, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial Su, Harrisburg, IL 62946 Cover Design: Christopher J. Whelan, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Cover Illustration: Jean Eglinton, 2202 Hazel Dell Rd., Springfield, IL 62703 Erigenia Artist: Nancy Hart-Stieber, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Executive Committee of the Society - April 1992 to May 1993 President: Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 President-Elect: J. William Hammel, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, Springfield, IL 62701 Past President: Jon J. Duerr, Kane County Forest Preserve District, 719 Batavia Ave., Geneva, IL 60134 Treasurer: Mary Susan Moulder, 918 W. Woodlawn, Danville, IL 61832 Recording Secretary: Russell R. Kirt, College of DuPage, Glen EUyn, IL 60137 Corresponding Secretary: John E. Schwegman, Illinois Department of Conservation, Springfield, IL 62701 Membership: Lorna J. Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. -

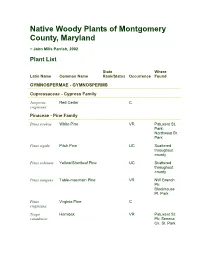

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Scientific Name Common Name NATURAL ASSOCIATIONS of TREES and SHRUBS for the PIEDMONT a List

www.rainscapes.org NATURAL ASSOCIATIONS OF TREES AND SHRUBS FOR THE PIEDMONT A list of plants which are naturally found growing with each other and which adapted to the similar growing conditions to each other Scientific Name Common Name Acer buergeranum Trident maple Acer saccarum Sugar maple Acer rubrum Red Maple Betula nigra River birch Trees Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Fagus grandifolia American beech Maple Woods Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-tree, yellow poplar Liquidamber styraciflua Sweetgum Magnolia grandiflora Southern magnolia Amelanchier arborea Juneberry, Shadbush, Servicetree Hamamelis virginiana Autumn Witchhazel Shrubs Ilex opaca American holly Ilex vomitoria*** Yaupon Holly Viburnum acerifolium Maple leaf viburnum Aesulus parvilflora Bottlebrush buckeye Aesulus pavia Red buckeye Carya ovata Shadbark hickory Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Halesia carolina Crolina silverbell Ilex cassine Cassina, Dahoon Ilex opaca American Holly Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-tree, yellow poplar Trees Ostrya virginiana Ironwood Prunus serotina Wild black cherry Quercus alba While oak Quercus coccinea Scarlet oak Oak Woods Quercus falcata Spanish red oak Quercus palustris Pin oak Quercus rubra Red oak Quercus velutina Black oak Sassafras albidum Sassafras Azalea nudiflorum Pinxterbloom azalea Azalea canescens Piedmont azalea Ilex verticillata Winterberry Kalmia latifolia Mountain laurel Shrubs Rhododenron calendulaceum Flame azalea Rhus copallina Staghorn sumac Rhus typhina Shining sumac Vaccinium pensylvanicum Low-bush blueberry Magnolia -

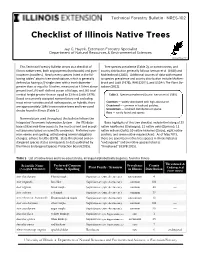

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Conservation Assessment for Butternut Or White Walnut (Juglans Cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region

Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2003 Jan Schultz Hiawatha National Forest Forest Plant Ecologist (906) 228-8491 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Juglans cinerea L. (butternut). This is an administrative review of existing information only and does not represent a management decision or direction by the U. S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was gathered and reported in preparation of this document, then subsequently reviewed by subject experts, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if the reader has information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. 2 Table Of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION / OBJECTIVES.......................................................................7 BIOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION..............................8 Species Description and Life History..........................................................................................8 SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS...........................................................................9 -

Ocean Drilling Program Initial Reports Volume

Ingle, J. C, Jr., Suyehiro, K., von Breymann, M. T., et al., 1990 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Initial Reports, Vol. 128 1. INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND, AND PRINCIPAL RESULTS OF LEG 128 OF THE OCEAN DRILLING PROGRAM, JAPAN SEA1 Shipboard Scientific Party2 INTRODUCTION in the northern Yamato Basin, first drilled during Leg 127, to conduct two major geophysical experiments aimed at detailing The Japan Sea has been widely viewed as a prime example the structure of the deep crust and upper mantle beneath the of a back-arc basin ever since the emergence of plate tectonic Japan Sea (Fig. 2). We successfully accomplished all of these concepts of convergent margin evolution (Karig, 1971). Abys- tasks. In addition, we cored 190 m into the Miocene volcanic sal water depths exceeding 3000 m point to oceanic crust basement sequence beneath Site 794, initially penetrated beneath the western portions of the sea (Figs. 1 and 2). In during Leg 127, and conducted a pioneering microbiological contrast, tectonically emplaced shallow sills (<150 m) sepa- sampling program at Site 798 to establish the distribution and rate the sea from the adjacent Pacific Ocean and dictate its role of bacteria in the diagenesis of deep marine sediments. unusual oceanographic behavior (Fig. 1). The geology and The new data amassed through Legs 127 and 128 drilling geophysical structure of the Japanese Islands leave no doubt and through geophysical experiments provide heretofore un- regarding the presence of continental crust beneath the Japan available constraints on the timing, rates, and style of forma- Arc, and multiple evidence demonstrates that structurally tion of the deep basins, ridges, and rises of the eastern and isolated continental fragments are present in the Japan Sea central Japan Sea. -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

Brewing Beer with Native Plants (Seasonality)

BREWING BEER WITH INDIANA NATIVE PLANTS Proper plant identification is important. Many edible native plants have poisonous look-alikes! Availability/When to Harvest Spring. Summer. Fall Winter . Year-round . (note: some plants have more than one part that is edible, and depending on what is being harvested may determine when that harvesting period is) TREES The wood of many native trees (especially oak) can be used to age beer on, whether it be barrels or cuttings. Woods can also be used to smoke the beers/malts as well. Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis): Needles and young twigs can be brewed into a tea or added as ingredients in cooking, similar flavoring to spruce. Tamarack (Larix laricina): Bark and twigs can be brewed into a tea with a green, earthy flavor. Pine species (Pinus strobus, Pinus banksiana, Pinus virginiana): all pine species have needles that can be made into tea, all similar flavor. Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana): mature, dark blue berries and young twigs may be made into tea or cooked with, similar in flavor to most other evergreen species. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba): edible fruit, often described as a mango/banana flavor hybrid. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum): root used to make tea, formerly used to make rootbeer. Similarly flavored, but much more earthy and bitter. Leaves have a spicier, lemony taste and young leaves are sometimes used in salads. Leaves are also dried and included in file powder, common in Cajun and Creole cooking. Northern Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Ripe, purple-brown fruits are edible and sweet. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra): mature red-purple-black fruit is sweet and juicy. -

Edible Perennial Gardening and Landscaping”

“Edible Perennial Gardening and Landscaping” PLANTS NUTS: Chinese Chestnut (Castanea mollissima), Black Walnut (Juglans nigra), Heartnut (Juglans cordifolia), Buartnut (Juglans x bisbyi), Northern Pecan (Carya illinoiensis), Shellbark Hickory (Carya laciniosa), Hican (Carya illinoensis x ovata), Hardy Almond (Prunus amygdalus), Korean Nut Pine (Pinus koraiensis), Hazelnut (Corylus spp.) FRUITS: Mulberry (Morus nigra, M. rubra, M. alba), Chinese Mulberry (Cudrania tricuspidata), Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium), Sour Cherry (Prunus cerasus), Nanking Cherry (Prunus tomentosa), Bush Cherry (Prunus japonica x P. jacquemontii), Quince (Cydonia oblonga), Apple Malus spp.), European Pear (Pyrus communis), Asian Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia), Shipova (Sorbus x Pyrus), Peach (Prunus persica), American Plum (Prunus americana), Beach Plum (Prunus maratima), Juneberry (Amelanchier spp.), Pawpaw (Asimina triloba), Hardy Orange (Poncirus trifoliata), Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas), Goumi (Elaeagnus multiflora), Goji (Lycium barbarum), Seaberry (Hippophae rhamnoides), Honeyberry (Lonicera kamchatika), Currants and Gooseberries (Ribes spp.), Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa), American Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon), Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), Raspberry (Rubus idaeus), Thornless Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus), Strawberries (Fragaria spp.), Hardy Kiwi (Actinidia arguta, A. kolomikta), Grape (Vitis spp.), Sandra Berry (Shisandra chinensis), Rugosa Rose (Rosa -

Steinbauer, MJ, Field, R., Grytnes, J

This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Steinbauer, M. J., Field, R., Grytnes, J.-A., Trigas, P., Ah-Peng, C., Attorre, F., Birks, H. J. B., Borges, P. A. V., Cardoso, P., Chou, C.-H., De Sanctis, M., de Sequeira, M. M., Duarte, M. C., Elias, R. B., Fernández-Palacios, J. M., Gabriel, R., Gereau, R. E., Gillespie, R. G., Greimler, J., Harter, D. E. V., Huang, T.-J., Irl, S. D. H., Jeanmonod, D., Jentsch, A., Jump, A. S., Kueffer, C., Nogué, S., Otto, R., Price, J., Romeiras, M. M., Strasberg, D., Stuessy, T., Svenning, J.-C., Vetaas, O. R. and Beierkuhnlein, C. (2016), Topography-driven isolation, speciation and a global increase of endemism with elevation. Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 25: 1097– 1107, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12469. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Manuscript in press in Global Ecology and Biogeography Topography-driven isolation, speciation and a global increase of endemism with elevation Manuel J. Steinbauer1,2, Richard Field3, John-Arvid Grytnes4, Panayiotis Trigas5, Claudine Ah-Peng6, Fabio Attorre7, H. John B. Birks4,8 Paulo A.V. Borges9, Pedro Cardoso9,10, Chang-Hung Chou11, Michele De Sanctis7, Miguel M. de Sequeira12, Maria C. Duarte13,14, Rui B. Elias9, José María Fernández-Palacios15, Rosalina Gabriel9, Roy E. Gereau16, Rosemary G. Gillespie17, Josef Greimler18, David E.V. Harter1, Tsurng-Juhn Huang11, Severin D.H. Irl1 , Daniel Jeanmonod19, Anke Jentsch20, Alistair S. Jump21, Christoph Kueffer22, Sandra Nogué23,4, Rüdiger Otto15, Jonathan Price24, Maria M.