Pignut Hickory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree Mycorrhizal Type Predicts Within‐Site Variability in the Storage And

Received: 6 December 2017 | Accepted: 8 February 2018 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14132 PRIMARY RESEARCH ARTICLE Tree mycorrhizal type predicts within-site variability in the storage and distribution of soil organic matter Matthew E. Craig1 | Benjamin L. Turner2 | Chao Liang3 | Keith Clay1 | Daniel J. Johnson4 | Richard P. Phillips1 1Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA Abstract 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Forest soils store large amounts of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), yet how predicted Balboa, Ancon, Panama shifts in forest composition will impact long-term C and N persistence remains 3Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Management, Institute of Applied Ecology, poorly understood. A recent hypothesis predicts that soils under trees associated Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang, with arbuscular mycorrhizas (AM) store less C than soils dominated by trees associ- China ated with ectomycorrhizas (ECM), due to slower decomposition in ECM-dominated 4Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, USA forests. However, an incipient hypothesis predicts that systems with rapid decom- position—e.g. most AM-dominated forests—enhance soil organic matter (SOM) sta- Correspondence Matthew E. Craig, Department of Biology, bilization by accelerating the production of microbial residues. To address these Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. contrasting predictions, we quantified soil C and N to 1 m depth across gradients of Email: [email protected] ECM-dominance in three temperate forests. By focusing on sites where AM- and Funding information ECM-plants co-occur, our analysis controls for climatic factors that covary with myc- Biological and Environmental Research, Grant/Award Number: DE-SC0016188; orrhizal dominance across broad scales. -

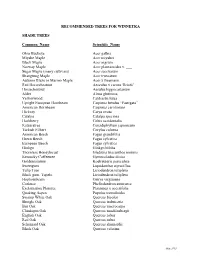

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Erigenia : Journal of the Southern Illinois Native Plant Society

ERIGENIA THE LIBRARY OF THE DEC IS ba* Number 13 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 1994 ^:^;-:A-i.,-CS..;.iF/uGN SURVEY Conference Proceedings 26-27 September 1992 Journal of the Eastern Illinois University Illinois Native Plant Society Charleston Erigenia Number 13, June 1994 Editor: Elizabeth L. Shimp, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial St., Harrisburg, IL 62946 Copy Editor: Floyd A. Swink, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Publications Committee: John E. Ebinger, Botany Department, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920 Ken Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. 1 Box 495 A, Westville, IL 61883 Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 Lawrence R. Stritch, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial Su, Harrisburg, IL 62946 Cover Design: Christopher J. Whelan, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Cover Illustration: Jean Eglinton, 2202 Hazel Dell Rd., Springfield, IL 62703 Erigenia Artist: Nancy Hart-Stieber, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Executive Committee of the Society - April 1992 to May 1993 President: Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 President-Elect: J. William Hammel, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, Springfield, IL 62701 Past President: Jon J. Duerr, Kane County Forest Preserve District, 719 Batavia Ave., Geneva, IL 60134 Treasurer: Mary Susan Moulder, 918 W. Woodlawn, Danville, IL 61832 Recording Secretary: Russell R. Kirt, College of DuPage, Glen EUyn, IL 60137 Corresponding Secretary: John E. Schwegman, Illinois Department of Conservation, Springfield, IL 62701 Membership: Lorna J. Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. -

Beyond the Fringe

Beyond the Fringe By Margaret Klein Wilson, Fairfax Master Gardener Intern The final flourish of native spring flowering trees belongs to fringe trees (Chionanthus virginicus). The measured parade of seasonal color — dogwoods and redbuds, flowering cherry and plum — is neatly capped by the fluttering grace of abundant white blossoms that engulf this small, often edge habitat tree beginning in mid-May. Encountering a fringe tree on a breezy spring day is to see masses of white corollas of petals casting their light perfume across the landscape. Is it any wonder Linnaeus named Yale ©2021 Copyright and noted this genus Chionanthus (chion = University snow; anthos = flower) as he compiled the photo: Genera Plantarum (1753)? Less poetically, fringe tree’s common names include Old Man’s Beard, Grancy graybeard, flowering ash and white fringe tree. Genus Chionanthus is a member of the Olive Family, the Olaceae, which includes 29 genera and over 600 species of trees and shrubs common in southeastern Asia and Australasia. Trees in this genus have uses both practical and ornamental: olive for food, ash for its lumber, and forsythia, gardenia and privets for sheer domestic beauty. In North America, ash trees in the genus Fraxinus, devilwood (Osmantus americanus) and Forestiera (swampprivet) are fringe tree’s near relatives. Only two species of fringe tree exist: C. virginicus in eastern North America and C. retusus, native to China. In his citation naming fringe tree the Virginia Native Plant Society 1997 Wildflower of the Year, C. F. Saachi explains this geographic disconnect: “This unusual biogeographic pattern, with different species within a genus … separated by several thousand miles, is a product of major geologic events including mountain building and the effects of glaciation. -

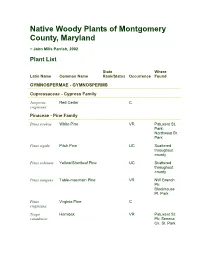

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

Effects of Root Pruning on Germinated Pecan Seedlings

PROPAGATION AND TISSUE CULTURE HORTSCIENCE 50(10):1549–1552. 2015. if pruning the roots shortly after germination stimulates lateral root formation. Similarly, little work has been attempted to consider Effects of Root Pruning on Germinated the effects of taproot pruning in young pecan seedlings back to different lengths on root Pecan Seedlings regeneration. The objective of this study 1 was to determine if root pruning at different Rui Zhang, Fang-Ren Peng , Pan Yan, Fan Cao, periods after seed germination affects pecan and Zhuang-Zhuang Liu seedling root and shoot growth and to evaluate College of Forestry, Nanjing Forestry University, 159 Longpan Road, different degrees of taproot pruning on root Nanjing 210037, China initiation. Dong-Liang Le Materials and Methods College of Forestry, Nanjing Forestry University, 159 Longpan Road, Nanjing 210037, China; and Nanjing Green Universe Pecan Science and The test was established at Lvzhou Pecan Research Station, Nanjing, China (lat. Technology Co. Ltd., 38 Muxuyuan Street, Nanjing 210007, China 32.05°N, long. 118.77°E). Open-pollinated Peng-Peng Tan seeds of the Chinese selection ‘Shaoxing’ were used as seed stock to produce seedlings. College of Forestry, Nanjing Forestry University, 159 Longpan Road, ‘Shaoxing’ had a small nut of very good Nanjing 210037, China quality with 50% percentage fill. The seeds averaged 30.4 mm in length, 20.9 mm in Additional index words. Carya illinoinensis, taproot, lateral root, shoot growth width, and 5.4 g in weight. Seeds were Abstract. Root systems of pecan trees are usually dominated by a single taproot with few collected on 7 Nov. -

Juniperus Occidentalis

Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) FEIS Home Page Table of Contents • SUMMARY INTRODUCTORY DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS FIRE EFFECTS AND MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS APPENDICES REFERENCES Figure 1—Western juniper. Photo by Joseph M. DiTomaso, University of California-Davis, Bugwood.org. Citation: Fryer, Janet L.; Tirmenstein, D. 2019 (revised from 1999). Juniperus occidentalis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/junocc/all.html [2019, June 26]. Revisions: The Taxonomy, Botanical and Ecological Characteristics, and Fire Effects and Management sections of this Species Review were revised in March 2019. New primary literature and a review by Miller et al. [145] were incorporated and are cited throughout this review. SUMMARY Western juniper occurs in the Pacific Northwest, California, and Nevada. Old-growth western juniper stands that established in presettlement times (before the 1870s) occur primarily on sites of low productivity such as claypan soils, rimrock, outcrops, the edges of mesas, and upper slopes. They are generally very open and often had sparse understories. Western juniper has established and spread onto low slopes and valleys in many areas, especially areas formerly dominated by mountain big sagebrush. These postsettlement stands (woodland transitional communities) are denser than most presettlement and old-growth woodlands. They have substantial shrub understories in early to midsuccession. Western juniper establishes from seed. Seed cones are first produced around 20 years of age, but few are produced until at least 50 years of age. Mature western junipers produce seeds nearly every year, although seed production is highly variable across sites and years. -

Brewing Beer with Native Plants (Seasonality)

BREWING BEER WITH INDIANA NATIVE PLANTS Proper plant identification is important. Many edible native plants have poisonous look-alikes! Availability/When to Harvest Spring. Summer. Fall Winter . Year-round . (note: some plants have more than one part that is edible, and depending on what is being harvested may determine when that harvesting period is) TREES The wood of many native trees (especially oak) can be used to age beer on, whether it be barrels or cuttings. Woods can also be used to smoke the beers/malts as well. Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis): Needles and young twigs can be brewed into a tea or added as ingredients in cooking, similar flavoring to spruce. Tamarack (Larix laricina): Bark and twigs can be brewed into a tea with a green, earthy flavor. Pine species (Pinus strobus, Pinus banksiana, Pinus virginiana): all pine species have needles that can be made into tea, all similar flavor. Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana): mature, dark blue berries and young twigs may be made into tea or cooked with, similar in flavor to most other evergreen species. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba): edible fruit, often described as a mango/banana flavor hybrid. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum): root used to make tea, formerly used to make rootbeer. Similarly flavored, but much more earthy and bitter. Leaves have a spicier, lemony taste and young leaves are sometimes used in salads. Leaves are also dried and included in file powder, common in Cajun and Creole cooking. Northern Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Ripe, purple-brown fruits are edible and sweet. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra): mature red-purple-black fruit is sweet and juicy. -

25Th U.S. Department of Agriculture Interagency Research Forum On

US Department of Agriculture Forest FHTET- 2014-01 Service December 2014 On the cover Vincent D’Amico for providing the cover artwork, “…and uphill both ways” CAUTION: PESTICIDES Pesticide Precautionary Statement This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife--if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides and pesticide containers. Product Disclaimer Reference herein to any specific commercial products, processes, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recom- mendation, or favoring by the United States government. The views and opinions of wuthors expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the United States government, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C.