Naturalization of Almond Trees (Prunus Dulcis) in Semi-Arid Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA Spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION for COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE By Ana Maria Metaxas Approved: James Hill Craddock Jennifer Boyd Professor of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) Gregory Reighard Jeffery Elwell Professor of Horticulture Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE by Ana Maria Metaxas A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Chestnut cultivars were evaluated for their commercial applicability under the environmental conditions in Hamilton County, TN at 35°13ꞌ 45ꞌꞌ N 85° 00ꞌ 03.97ꞌꞌ W elevation 230 meters. In 2003 and 2004, 534 trees were planted, representing 64 different cultivars, varieties, and species. Twenty trees from each of 20 different cultivars were planted as five-tree plots in a randomized complete block design in four blocks of 100 trees each, amounting to 400 trees. The remaining 44 chestnut cultivars, varieties, and species served as a germplasm collection. These were planted in guard rows surrounding the four blocks in completely randomized, single-tree plots. In the analysis, we investigated our collection predominantly with the aim to: 1) discover the degree of acclimation of grower- recommended cultivars to southeastern Tennessee climatic conditions and 2) ascertain the cultivars’ ability to survive in the area with Cryphonectria parasitica and other chestnut diseases and pests present. -

Essential Wholesale & Labs Carrier Oils Chart

Essential Wholesale & Labs Carrier Oils Chart This chart is based off of the virgin, unrefined versions of each carrier where applicable, depending on our website catalog. The information provided may vary depending on the carrier's source and processing and is meant for educational purposes only. Viscosity Absorbtion Comparible Subsitutions Carrier Oil/Butter Color (at room Odor Details/Attributes Rate (Based on Viscosity & Absorbotion Rate) temperature) Description: Stable vegetable butter with a neutral odor. High content of monounsaturated oleic acid and relatively high content of natural antioxidants. Offers good oxidative stability, excellent Almond Butter White to pale yellow Soft Solid Fat Neutral Odor Average cold weather stability, contains occlusive properties, and can act as a moistening agent. Aloe Butter, Illipe Butter Fatty Acid Compositon: Palmitic, Stearic, Oleic, and Linoleic Description: Made from Aloe Vera and Coconut Oil. Can be used as an emollient and contains antioxidant properties. It's high fluidiy gives it good spreadability, and it can quickly hydrate while Aloe Butter White Soft Semi-Solid Fat Neutral Odor Average being both cooling and soothing. Fatty Acid Almond Butter, Illipe Butter Compostion: Linoleic, Oleic, Palmitic, Stearic Description: Made from by combinging Aloe Vera Powder with quality soybean oil to create a Apricot Kernel Oil, Broccoli Seed Oil, Camellia Seed Oil, Evening Aloe Vera Oil Clear, off-white to yellow Free Flowing Liquid Oil Mild musky odor Fast soothing and nourishing carrier oil. Fatty Acid Primrose Oil, Grapeseed Oil, Meadowfoam Seed Oil, Safflower Compostion: Linoleic, Oleic, Palmitic, Stearic Oil, Strawberry Seed Oil Description: This oil is similar in weight to human sebum, making it extremely nouirshing to the skin. -

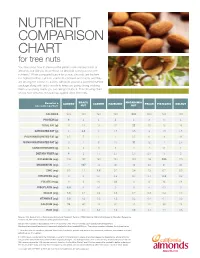

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Is Peanut Butter Keto-Friendly?

Is Peanut Butter Keto-Friendly? Yes! Peanut butter contains carbohydrates, fat, and protein; the ratios of those macronutrients are what makes it acceptable for a keto diet. Our Once Again peanut butters that are made with one simple ingredient: peanuts, are a healthy addition to your keto diet. Peanuts are in the legume family, which includes a variety of beans. Generally speaking, legumes are not included in keto diets; however, peanuts have a higher fat content than other beans which makes them keto-friendly. Moreover, peanuts have a similar macronutrient distribution when compared to nuts such as almonds. They are high in fat and lower in carbs, and thus make a perfect food for the keto lifestyle. Peanut butter fits nicely into your keto diet as a dip for celery, or add it to smoothies, or experiment with it as an ingredient in salad dressings. Is Almond Butter Keto- Friendly? Yes! Almond butter is a staple for most following a keto lifestyle. Used often as a versatile ingredient in salad dressings, dips, and sauces, and in many other culinary innovations, nut butters in general have the desired macronutrient ration for a keto diet, and almond butter is a particularly good choice because of its fiber and vitamin E content. Most of our almond butters contain one simple ingredient: almonds. The newest addition to our product line is our Blanched Almond Butter, available in both in Extra Creamy and Crunchy varieties. Once Again Blanched Almond Butters contain only one gram of carbohydrate per serving! Blanching almonds involves removing the exterior of the almond, leaving behind a surprisingly nutty-sweet interior, with its lighter texture and color. -

Tea Seed Oil and Health Properties Fatih Seyis1, Emine

Tea Seed Oil and Health Properties Fatih Seyis1, Emine Yurteri1, Aysel Özcan1 1Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University: Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Science, Field Crops Department, Rize/Turkey, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Tea Oil has a mild fragrant flavor that goes with anything. It’s not a heavy oil like Olive Oil, but thinner – more like almond oil. If the taste or “oiliness” of olive oil overpowers your food. Along with its mild taste and pleasant tea-like aroma, this oil touts impressive health benefits. Tea seed oil has a high smoke point, contains more monounsaturated fatty acids than olive oil, contains fewer saturated fatty acids than olive oil, contains high levels of Vitamin E, polyphenol antioxidants and both Omegas 3 and 6, but has less Omega 6 and Polyunsaturated Fats than olive oil. Health Benefits of tea seed oil are: it can be applied topically and consumed internally to obtain its health benefits, camellia oil can be used for skin, hair, has anti-cancer effects, effects boost immunity and reduces oxidative stress. Camellia oil is used for a variety of other purposes, for example for cooking, as machinery lubricant, as ingredient in beauty products like night creams, salves, in hair care products and perfumes and is used to coat iron products to prevent rusting. Key words: Tea, seed oil, health 1. Introduction Like other genera of Camellia (from Theaceae family), the tea plant (C.sinensis) produces large oily seeds. In some countries where tea seed oil is abundantly available, it has been accepted as edible oil (Sahari et al., 2004). -

Bioactive Compounds in Nuts and Edible Seeds: Focusing on Brazil Nuts and Baru Almond of the Amazon and Cerrado Brazilian Biomes

Review Article SM Journal of Bioactive Compounds in Nuts and Nutrition and Edible Seeds: Focusing on Brazil Nuts Metabolism and Baru Almond of the Amazon and Cerrado Brazilian Biomes Egea MB1*, Lima DS1, Lodete AR1 and Takeuchi K1,2* 1Science and Technology, Goiano Institute of Education, Brazil 2Faculty of Nutrition, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil Article Information Abstract Received date: Oct 09, 2017 The biodiversity of the Amazon and Cerrado biomes is extremely important for the populations that inhabit Accepted date: Nov 14, 2017 these areas, through the extractive collection of non-timber forest products such as fruits, nuts and edible seeds, which generate income and employment. Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is native from South America being Published date: Nov 20, 2017 found in the Amazon biome and baru almond (Dipteryx alata Vog.) is native from the Cerrado biome; these are part of the group of oleaginous that can be classified as true nuts and edible seeds, respectively. Both *Corresponding author are important sources of micronutrients that have been associated with several benefits to human health due to the presence of high levels of biologically active compounds such as minerals and vitamins. Minerals act Egea MB, Science and Technology, mostly as cofactors in various reactions, selenium has high availability in Brazil nuts and from selenocysteine Goiano Institute of Education, Brazil, and its enzymes, it exerts functions in the human body as an antioxidant, regulator of thyroid hormones and Tel: +55 64 36205636; protection of cardiovascular diseases. Among vitamins, tocopherol is a precursor to vitamin E, present in both Brazil nut and baru almond, being found in the form of α-tocopherol and having a role in the prevention of various Email: [email protected] diseases, including: cancer, diabetes, cataracts and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. -

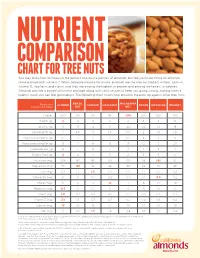

Chart for Tree Nuts

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART FOR TREE NUTS You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the highest in protein and among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a healthy snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT Calories 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 Protein (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 Total Fat (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 18 Saturated Fat (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 Polyunsaturated Fat (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 Monounsaturated Fat (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 Carbohydrates (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 Dietary Fiber (g) 4 2 1 3 2 3 3 2 Potassium (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 Magnesium (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 Zinc (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 Vitamin B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 Folate (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 Riboflavin (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 Niacin (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 Vitamin E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 Calcium (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 Iron (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Almond Cashew Barfi Recipe

150 Jackson St, Petone T: 568 4149 E: [email protected] ALMOND CASHEW BARFI RECIPE Almond Walnut Cashew Barfi is a healthy, quality substitute for candy that your entire family will enjoy Ingredients Makes 24 pcs 1/2 c almonds 1/2 c water 1/2 c walnuts 1/2 tsp cardamom powder 1/2 c cashew nuts 1 Tbsp sliced almonds to garnish 1 1/4 c sugar Method 1. Dry grind the walnuts, cashews and almonds in a food processor. 2. Dry roast the grounded nuts in a frying pan on low medium heat. 3. Roast them just enough so that the nuts start to give off an aroma. It will take about 4 to 5 minutes. Remove from heat and set aside. 4. Put the sugar and water together in a saucepan on medium heat. Bring to a boil to make the 1 thread syrup or on the candy thermometer it should reach 230 degrees F. 5. Turn off the heat and stir in the cardamom powder. 6. Add the nuts to the syrup and mix, and then spread over a greased 8-inch plate. Note: don’t let the syrup cool off. It must be spread while still hot. 7. Wait a few minutes until barfi is set but still soft. 8. Then cut the barfi into any shape you like (such as square, diamond, triangle). 9. Garnish each piece of barfi with sliced almonds while the barfi is still soft. 10. Allow the barfi to cool for about an hour to dry and hold its shape. -

Castanea Sativa Mill

Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group Tree factsheet images at pages 3, 4, 5, 6 Castanea sativa Mill. taxonomy author, year Miller, … synonym C. vesca Gaertn. Family Fagaceae Eng. Name Sweet Chestnut tree, Spanish Chestnut, European Chestnut Dutch name Tamme kastanje subspecies - varieties - hybrids - cultivars, frequently used references Weeda 2003, Nederlandse oecologische flora, vol.1 (Dutch) PFAF database http://www.pfaf.org/index.html morphology crown habit tree, round max. height (m) 30 max. dbh (cm) 300 actual size Europe 2000? years old, d(..) 197, Etna, Sicily , Italy actual size The Netherlands year 1600-1700, d (130) 270, h 25, Kabouterboom, Beek-Ubbergen year 1810-1820, d(130) 149, h 30 leaf length (cm) 10-27 leaf petiole (cm) 2-3 leaf colour upper surface green leaf colour under surface green leaves arrangement alternate flowering June flowering plant monoecious flower monosexual flower diameter (cm) 1 flower male catkins length (cm) 8-12 pollination wind fruit; length burr (Dutch: bolster) containing 2-3 nuts; 6-8 cm fruit petiole (cm) 1 seed; length nut; 5-6 cm seed-wing length (cm) - weight 1000 seeds (g) 300-1000 seeds ripen September seed dispersal rodents: Apodemus -species – Wood mice - bosmuizen rodents: Sciurus vulgaris - Squirrel - Eekhoorn birds: Garulus glandarius – Jay –Gaai habitat natural distribution Europe, West Asia in N.W. Europe since 9000 B.C. natural areas The Netherlands forests geological landscape types The Netherlands loss-covered terraces, ice pushed ridges (Hoek 1997) forested areas The Netherlands loamy and sandy soils. area Netherlands < 1700 (2002, Probos) % of forest trees in the Netherlands < 0,7 (2002, Probos) soil type pH-KCl indifferent soil fertility nutrient medium to rich light highly shade tolerant as a sapling, shade tolerant when mature shade tolerance 3.2 (0=no tolerance to 5=max. -

Production, Pomological and Nutraceutical Properties of Apricot

1 Production, pomological and nutraceutical properties of apricot Khaled Moustafa1* and Joanna Cross2 1Editor of ArabiXiv (arabixiv.org), Paris, France 2Nigde Omer Halisdemir University, Nigde, Turkey Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Apricot (Prunus sp.) is an important fruit crop worldwide. Despite recent advances in apricot research, much is still to be done to improve its productivity and environmental adaptability. The availability of wild apricot germplasms with economically interesting traits is a strong incentive to increase research panels toward improving its economic, environmental and nutritional characteristics. New technologies and genomic studies have generated a large amount of raw data that the mining and exploitation can help decrypt the biology of apricot and enhance its agronomic values. Here, we outline recent findings in relation to apricot production, pomological and nutraceutical properties. In particular, we retrace its origin from central Asia and the path it took to attain Europe and other production areas around the Mediterranean basin while locating it in the rosaceae family and referring to its genetic diversities and new attempts of classification. The production, nutritional, and nutraceutical importance of apricot are recapped in an easy readable and comparable way. We also highlight and discuss the effects of late frost damages on apricot production over different growth stages, from swollen buds to green fruits formation. Issues related to the length of production season and biotic and abiotic environmental challenges are also discussed with future perspective on how to lengthen the production season without compromising the fruit quality and productivity. Keywords Apricot kernel oil, plum pox virus, prunus armeniaca, spring frost, stone fruit, sharka. -

Nutritive Value and Degradability of Leaves from Temperate Woody Resources for Feeding Ruminants in Summer

3rd European Agroforestry Conference Montpellier, 23-25 May 2016 Silvopastoralism (poster) NUTRITIVE VALUE AND DEGRADABILITY OF LEAVES FROM TEMPERATE WOODY RESOURCES FOR FEEDING RUMINANTS IN SUMMER Emile JC 1*, Delagarde R 2, Barre P 3, Novak S 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] mailto:(1) INRA, UE 1373 FERLUS, 86600 Lusignan, France (2) INRA, UMR 1348 INRA-Agrocampus Ouest, 35590 Saint-Gilles, France (3) INRA, UR 4 URP3F, 86600 Lusignan, France 1/ Introduction Integrating agroforestry in livestock farming systems may be a real opportunity in the current climatic, social and economic conditions. Trees can contribute to improve welfare of grazing ruminants. The production of leaves from woody plants may also constitute a forage resource for livestock (Papanastasis et al. 2008) during periods of low grasslands production (summer and autumn). To know the potential of leaves from woody plants to be fed by ruminants, including dairy females, the nutritive value of these new forages has to be evaluated. References on nutritive values that already exist for woody plants come mainly from tropical or Mediterranean climatic conditions (http://www.feedipedia.org/) and very few data are currently available for the temperate regions. In the frame of a long term mixed crop-dairy system experiment integrating agroforestry (Novak et al. 2016), a large evaluation of leaves from woody resources has been initiated. The objective of this evaluation is to characterise leaves of woody forage resources potentially available for ruminants (hedgerows, coppices, shrubs, pollarded trees), either directly by browsing or fed after cutting. This paper presents the evaluation of a first set of 12 woody resources for which the feeding value is evaluated through their protein and fibre concentrations, in vitro digestibility (enzymatic method) and effective ruminal degradability. -

The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity

Article The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity Mauro De Feudis 1,* , Gloria Falsone 1, Gilmo Vianello 2 and Livia Vittori Antisari 1 1 Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, Via Fanin, 40, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (L.V.A.) 2 Centro Sperimentale per lo Studio e l’Analisi del Suolo (CSSAS), Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 June 2020; Accepted: 19 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Recently, several hectares of abandoned chestnut forests (ACF) were recovered into chestnut stands for nut or timber production; however, the effects of such practice on soil mineral horizon properties are unknown. This work aimed to (1) identify the better chestnut forest management to maintain or to improve the soil properties during the ACF recovery, and (2) give an insight into the effect of unmanaged to managed forest conversion on soil properties, taking in consideration sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest ecosystems. The investigation was conducted in an experimental chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest located in the northern part of the Apennine chain (Italy). We identified an ACF, a chestnut forest for wood production (WCF), and chestnut forests 1 for nut production with a tree density of 98 and 120 plants ha− (NCFL and NCFH, respectively). WCF, NCFL and NCFH stands are the result of the ACF recovery carried out in 2004.