Novels of Alejandro Sawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Émile Zola: El Olor De La Tierra

Émile Zola: el olor de la tierra A poco más de cien años de la muerte de Émile Zola, su obra es más citada que leída. Los “Rougon Macquart”, sin embargo, merecen una buena inmersión, y en su compleja arquitectura figuran bloques como “Germinal” o “La bestia humana”, que están entre las mejores novelas francesas de todos los tiempos. Texto: Carles Barba De los cinco colosos que sustentan el edificio de la gran novela realista francesa (Stendhal, Balzac, Flaubert, Zola y Proust), el penúltimo ha sido durante el siglo XX el menos leído y el más cuestionado. Ya Gide se dolía del hecho en una anotación de su Diario: “Considero el descrédito actual de Zola como una monstruosa injusticia que no honra a los críticos de hoy en día. No ha habido novelista más personal ni más representativo”. Tal negligencia contrastaría con el papel central que jugó Zola en su propia época como chef d’école del movimiento naturalista (aglutinando a su alrededor a colegas como Maupassant, Huysmans o Céard) y con la enorme influencia que sus ideas y su obra tuvieron en otras literaturas coetáneas; en particular, sobre la española y catalana. En efecto, narradores del fuste de Pardo Bazán, Clarín, Galdós y Blasco Ibáñez absorbieron a su modo las teorías deterministas defendidas por el francés en su manifiesto La novela experimental (1880) y, en Catalunya, Narcís Oller recabó de él un prólogo militante para su relato La papallona . El naturalismo zolesco irradiará también hacia Estados Unidos y Rusia, y la complacencia en la descripción de lo bajo y ruin se reflejará lo mismo en los novelones de un Thomas Wolfe o un Frank Norris que en los amplios frescos sociales surgidos al calor de la Revolución de 1917. -

LA RECEPCIÓN DE LAS NOVELAS DE ZOLA Y DE PARDO BAZÁN EN LA PRENSA ESPAÑOLA DE LA ÉPOCA František Dratva

LA RECEPCIÓN DE LAS NOVELAS DE ZOLA Y DE PARDO BAZÁN EN LA PRENSA ESPAÑOLA DE LA ÉPOCA František Dratva Abstract: The article deals with the reception of Émile Zola's novels and Emilia Pardo Bazán's Los pazos de Ulloa in Spanish press in the late nineteenth century. In each case, five articles were taken as a source and the intention was to reflect the most important opinions and their developments. Keywords: Émile Zola; Emilia Pardo Bazán; Naturalism; Reception; Press. Resumen: El artículo analiza la recepción que tuvieron en los periódicos españoles de finales del siglo XIX las novelas de Émile Zola y Los pazos de Ulloa de Emilia Pardo Bazán. En cada caso se han tomado como fuente cinco artículos y se ha pretendido reflejar las opiniones más relevantes y la evolución de las mismas. Palabras clave: Émile Zola; Emilia Pardo Bazán; Naturalismo; Recepción; Prensa. 1. Nota introductoria En el presente trabajo se analizará cómo fueron recibidas en España las novelas de Émile Zola durante el periodo comprendido entre 1882 y 1890, y cómo fue acogida la novela Los pazos de Ulloa en los años 1886 y 1887. En el primer caso se tomarán como base los artículos publicados en el periódico El Imparcial —para mostrar la evolución y divergen- cia de las opiniones en la misma publicación—; en el segundo se recurrirá a los artículos aparecidos en El Liberal, La Dinastía, La Ilustración Ibérica y Galicia. Todas las reseñas han sido consultadas en la página web de la Hemeroteca Virtual, que forma parte de la Bi- blioteca Nacional de España. -

From the Inside: Getting Down to Business

the WEB EXCLUSIVE: Check thebreeze. org this weekend for Justin Thurmond's next movie review BreezeJames Madison University's Student Newspaper Volume 84, Issue 54 1 Thursday. April 24, 2008 From the Inside: Getting Down to Business BY AMY PASSAKEni Ihtitmt After whal fell like the most dit ticult semester of their lives, th- 1 BY TIM CHAPMAN members of Key Free Security ean Iht tmit walk away with a sense of ■ccoru plishment. a prestigious a Ward and most notably. $6,ooo. At about ±:'SO in the morning last Friday, an unlikely fig- This team ofsh business mtjoi ure toted a ratty old broom and dustpan through the V.I.P. won the sixth annual ('()B {on Bud lounge of the Rorktnwn Bar and Grill. ness Plan Competition. Sponsored With his hulking 6-foot-2, 240-pound-frame, Lov^H by JMU's College of Business and pears a bit out of place with the cleaning materials. I*t ir» the Executive Ad\isor> Council, tin just another "perk" to being the head of security ,it Harri- competition provides an opportu sonburg's hottest spot on Thursday nights. nit\ to win more than $25,000 in "It's peaceful now at least," JMU senior Drew I.oy says scholarships between each of th after releasing a long sigh. "Cleanup takes awhile, hut it feels top live teams. Nearly 150 poesfl>l like nothing compared to dealing with the people." teams, from over three Mm can be nominated or submit their The people, JMU students, age 21 or older, have left what own proposals for review. -

Seniors Say Goodbye to KDS

The Sun Devils’ Advocate Volume XLI, Number 6 Kent Denver School, 4000 East Quincy Avenue, Englewood, CO 80113 June 4, 2019 Seniors Say Goodbye To KDS Soul band SOUL’D OUT plays “I Want You Back” at Coffee House. Photo by Mika Fisher Student Run Continuation & Crisis in Service Commencement Venezuela Organization Awards See Page 5 See Page 11 See Page 13 Arts & Entertainment Winter. Is. Here. enemy to Winterfell after bending the knee to Bran out of a tower window many seasons ago. by Rachel Wagner warrior Christina Aguilera (thank you, Jona- Slightly awkward. than Van Ness). The northerners are quite con- *Spoilers ahead! You’ve been warned.* Tormund and his Wilding friends take a servative because they want their borders shut quick jaunt to the Least Hearth and find the Alright, “Game of Thrones” fans. Season and sealed. Even after Bran informs everyone White Walkers have beat them there. There is a seven left us with several cliff hangers. Jon that the Night King is about to stroll in with his big Fibonacci-like display of dismembered hu- and Dany were in some kind of relationship, undead army, the Winterfellians are still wary man arms surrounding an undead boy. Cheer- but we found out some disturbing information of their “guests.” A few reunions that are rather ing, right? about their familial relationship. All of the ma- sweet are that of Sansa and Tyrion and Jon and jor camps of people came together in King’s Arya. Some people have complained that this Landing in an attempt to get everyone to fight first episode was disappointing. -

José Antonio Vila Sánchez

El estilo sin sosiego. La génesis de la poética integradora de Javier Marías: 1970-1986 José Antonio Vila Sánchez TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2015 DIRECTOR DE LA TESI Dr. Domingo Ródenas de Moya DEPARTAMENT D’HUMANITATS A mis padres AGRADECIMIENTOS Esta tesis doctoral debe inmesamente a Domingo Ródenas de Moya, sin cuyo apoyo, ánimos, paciencia, meticulosidad, riguroso sentido crítico y sugerencias, no hubiera sido posible llevar a cabo el proyecto. Gracias también a Javier Marías que tuvo la amabilidad de recibirme y atender a mis preguntas. 5 RESUMEN Español La tesis analiza el contexto histórico y estético desde el cual situar la complejidad de la escritura literaria de Javier Marías. Se centra en los años formativos del novelista y propone una reconstrucción de los elementos genéticos de su poética literaria. La tesis consta de dos partes diferenciadas. En la primera de ellas se abarca el periodo 1970- 1975. Se estudia ahí el campo literario español de los años finales del franquismo y se muestra cómo las publicaciones del autor en ese tiempo son una consecuencia y a la vez una reacción a las transformaciones que se vivieron en España. En la segunda parte, se analizan las tres novelas publicadas por Marías entre 1975 y 1986, constatando cómo en su obra se armonizan elementos eminentemente narrativos con el rigor estilístico propio de la alta literatura, dando lugar a la «poética integradora» que ha definido su obra de madurez. English This thesis analyzes the historical and esthetical context in which to pinpoint the complexity of Javier Marías’ literary writing. It focuses on the novelist’s formative years and proposes a reconstruction of the genetical elements of his literary poetics. -

Tres-Cuadros.Pdf

EN LA ILUSTRACIÓN ESPAÑOLA Y AMERICANA, EL ECIJANO BENITO MAS Y PRAT, BAJO EL TITULO DE TRES CUADROS NATURALISTAS, EN DOS PARTES, LOS PUBLICÓ CON FECHA 30 DE AGOSTO Y 8 SEPTIEMBRE 1885. Agosto 2019 Ramón Freire Gálvez. Ya hemos dicho en más de una ocasión, que este ilustre ecijano escribió sobre diversos temas. Costumbrista al máximo, fueron muchos sus artículos que se publicaron en el siglo XIX, sobre todo en La Ilustración Española y Americana, que yo he me propuesto rescatar. En esta ocasión, en dos partes, escribe sobre el naturalismo, razonando sus teorías y con la calidad a que nos tiene acostumbrados y que decía así: TRES CUADROS NATURALISTAS. I. El deseo de erigirse en pontífices de escuelas literarias, de elevarse sobre los demás, de dictar leyes y de imponer guetos, ha llevado a muchas eminencias a tan enrarecidas atmósferas, que ellos han respirado con dificultad, y sus seguidores se han asfixiado, sin ganar el difícil Tabor de sus maestros. Racine y sus discípulos fatigaron al cabo a los espectadores, extremando los moldes clásicos; Góngora y los suyos involucraron la rica habla castellana, hasta el punto de hacer nacer la cultalatiniparla, y Goethe y Byron hicieron una colonia de plañideras desesperadas de los poetas y noveladores de su tiempo. Algo semejante acontece hoy en lo que a la literatura naturalista se refiere, y es preciso no entregarse a lamentables entremos. La tendencia naturalista, como la clásica y la romántica, puede traer, erigida en intransigente sistema, una decadencia tanto más sensible cuanto que habrá de estar en razón directa de los fines fatalistas y sensuales que forman su carácter distintivo en la actual etapa, notándose ya su huella, grafica, sí, pero dura y grosera a la vez, hasta en los dominios de las musas. -

M Usic , M Oviesand M

Nov.Nov. 3,3, 20052005 Music,M u s i c , MMovieso v i e s anda n d MoreM o r e ‘Saw II’ rips through theaters MUSIC: Neil YYoungoung, GZA and AAshleeshlee Simpson brbringing new music ttoo fanfanss MOVIE: ‘L‘Legendegend of ZZorro’orro’ makes marmark,k, ‘Nor‘Northth CCountry’ountry’ ttouchesouches audiencaudienceses MORE: RReadead fforor yyourour ststomach,omach, plus the lalatesttest enentertainmenttertainment newnewss 2 THE BUZZ the cover of the December-Janu- ary 2006 … Barbara Walters will Contents ary issue of Teen People. Jessica be presenting her “10 Most Fasci- Simpson, 25, a self-proclaimed nating People of 2005.” Some of THE ditz, tells the magazine she went to the infl uential people who made The Inside Buzz therapy during her publicity over- the cut include Kanye West, Sec- 02 I N S I D E load; sister Ashlee opens up about retary of State Condoleezza Rice her recent singing fl ops, like the and even Tom Mesereau, Michael 03 Girls That Rock Series - Part 3 infamous “Saturday Night Live” Jackson’s lawyer. The show will BUZZ lip-synching debacle and the Or- air on Nov. 29 on ABC at 10 p.m. ange Bowl fi asco … 33-year-old … Notable CD releases out Tues- 04 New Movie Reviews actress Gabrielle Union has sepa- day were Santana All That I Am rated from husband, Chris How- … Rammstein Rosenrot [Import] 05 New Movie Reviews ard, a former Jacksonville Jaguar … John Fogerty The Long Road running back. … Mary J. Blige Home: Ultimate John Fogerty 06 Flashback Favorite will receive the VLegend Award Creedence Collection … new By MAHSA KHALILIFAR from Vibe at the 3rd annual awards DVD releases this week include Daily Titan Asst. -

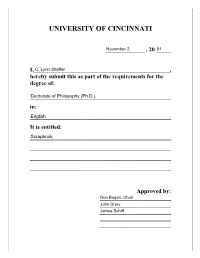

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ SCRAPBOOK A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by C. Lynn Shaffer B.A., Morehead State University, 1993 M.A., Morehead State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Don Bogen C. Lynn Shaffer Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, a collection of original poetry by C. Lynn Shaffer, consists of three sections, predominantly persona poems in narrative free verse form. One section presents the points of view of different individuals; the other sections are sequences that develop two central characters: a veteran living in modern-day America and the historical figure Secondo Pia, a nineteenth-century Italian lawyer and photographer whose name is not as well known as the image he captured -

Peña Y Goñi Et Zola: Une Preuve De Gratitude Intellectuelle

PENAYGONI ET ZOLA: UNE PREUVE DE GRATITUDE INTELLECTUELLE ENCARNACIÓN MEDINA ARJONA Universidad de Cádiz RESUMEN Antonio Peña y Goñi ha sido siempre reconocido como discípulo de la escuela naturalista. Sus crí- ticas musicales y sus obras literarias están marcadas por continuas referencias a Emile Zola. Recorriendo su trabajo de una y otra índole, reunimos en él las pruebas de una devoción inquebrantable al maestro fran- cés. A este propósito presentamos una carta inédita dirigida a Zola en 1892, en la que el musicólogo vasco le manifiesta su admiración y aprovecha para mostrarle su gratitud intelectual. Palabras clave: Peña y Goñi, Zola, naturalismo, recepción, correspondencia. RÉSUMÉ Antonio Peña y Goñi fut toujours reconnu comme disciple de l'école naturaliste. Ses critiques de musique et ses oeuvres littéraires sont parsemées de références à Emile Zola. Tout en parcourant son tra- vail sous ces deux facettes, nous y rassemblons les preuves d'un dévouement inébranlable envers le maî- tre français. A cette occasion nous proposons la lecture d'une lettre inédite, adressée à Zola en 1892, où le musicologue basque lui manifeste son admiration et en profite pour lui prouver sa gratitude intellectuelle. Mots-clés: Peña y Goñi, Zola, naturalisme, réception, correspondance. ABSTRACT Antonio Peña y Goñi has always been recognised as a disciple of the Naturalist school. His music critiques and literary works are marked by the continual references to Emile Zola. Looking through any of his works, we find they all possess evidence of his unshakeable devotion to the French master. With this in mind, we present a previously unpublished letter to Zola in 1892, in which the Basque musicologist shows Keywordshis admiratio: Peñn ana yd Goñitakes, thZolae opportunit, Naturalismy t,o Receptiondemonstrat, e Correspondenceto him his intellectua. -

Performance As a Site for Learning

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Visual Arts QUEERING OURSELVES: PERFORMANCE AS A SITE FOR LEARNING A Thesis in Art Education by Garnell E. Washington Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2005 ii Committee Page The thesis of Garnell E. Washington has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Yvonne M. Gaudelius Professor of Art Education & Women’s Studies Associate Dean, College of Arts & Architecture Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Marjorie Wilson Associate Professor of Art Education Christine Marme Thompson Professor of Art Education Professor In-Charge of Graduate Programs In Art Education Ian E. Baptiste Associate Professor of Education Mary Ann Stankiewicz Professor of Art Education Professor In-Charge of Art Education Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii Abstract The following study examines learning communities that are involved with art. It is an investigation of culture in action and community as interactivity. Here learning and culture are both examined “as” performance, as a happening only understood in hindsight, as an event that becomes known through experience. By employing queer criticism, I engage in a process of re-considering, re-investigating, and re-examining what I thought was familiar about the cultures that are near me. In this study I ask how various performances of my art classroom are and are not related to one another. In this report queer theory is combined with performance theory to articulate alternative notions of subjectivity. The combination of queer and performance theory is useful because it forces knowledge to be understood as activity. -

Free Monologues for Kids and Teens Pg

© Drama Notebook www.dramanotebook.com Free Monologues for Kids and Teens pg. 1 Copyright 2020 Published in the United States by Drama Notebook www.dramanotebook.com a division of Rumpelstiltskin Press, Portland Oregon USA All rights reserved. While this collection is free for teachers and students to use, it is copyright protected. Any commercial use is strictly prohibited without written permission from the publisher of this work. The monologues may be used in classrooms, performed in competitions, used in auditions, and performed as part of school/educational plays completely royalty- free. Please credit ‘Drama Notebook’ in all forms of performance. For commercial rights or other inquiries, please contact Janea Dahl at [email protected] Quick Copyright FAQ’s You may use these monologues freely with your students. You MAY share this PDF with your students via Google drive, email, or through your password protected teacher web page. You MAY print as many copies as you need for classroom use with your students. Your students MAY perform the monologues for class work, performances and competitions WITHOUT requesting permission, but students must cite the author and “published on Drama Notebook” in their recitation. Neither you nor your students may edit the monologues. You may NOT post the PDF on a web page that is searchable/view-able by the public. You may NOT email the collection to other teachers or educators. Rather, please refer them to Drama Notebook to obtain their own download. ENJOY! © Drama Notebook www.dramanotebook.com Free Monologues for Kids and Teens pg. 2 Free Monologues for Kids and Teens Written by kids and teens! Drama Notebook has created the world’s largest collection of original monologues written by children and teenagers. -

Il Giornalismo Vitalista Di Alejandro Sawa Luigi Motta

Il giornalismo vitalista di Alejandro Sawa Luigi Motta “Y como Alejandro Sawa, ciego, no inspira temor como antes, los que eran sus amigos le olvidan, y sus enemigos, ya que no pueden negarle, pretenden cobardemente borrar su nombre de la historia de la literatura española contemporánea.” Prudencio Iglesias Hermida Ormai dimenticato da molti anni, Alejandro Sawa ritornò in auge nella Spagna letteraria del primo quarto del secolo scorso grazie a Ramón del Valle-Inclán che dalle sue gesta e virtù trasse spunto per il protagonista di Luces de Bohemia con cui lo scrittore galiziano inaugurava i famosi esperpentos. Se nel periodo nel quale l’opera di Valle fu data alle stampe non fu immediato collegare il bohemio Max Estrella col sivigliano dall’eloquenza forbita, la formidabile memoria e un disdegno per tutto quanto avesse a che fare col filisteismo borghese, oggi grazie soprattutto agli studi di Zamora Vicente [1968-9] e Phillips [1976] e alle riedizioni di alcuni testi non rimangono più dubbi nel collegare il personaggio principale della pièce valleinclaniana con lo scrittore che trascorse parte della propria esistenza a Parigi e si distinse negli anni a cavallo tra XIX e XX secolo per un ruolo da primo attore nelle tertulias madrilene. Non sono sufficienti i numerosi attestati di stima che Don Ramón non lesinò durante il tratto di vita trascorso congiuntamente, né i ripetuti tentativi di sollecitare aiuti economici per l’amico ormai cieco e povero da molti anni e nemmeno i concreti interventi per pubblicare postumo l’ultimo scritto dell’andaluso