Performance As a Site for Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Inside: Getting Down to Business

the WEB EXCLUSIVE: Check thebreeze. org this weekend for Justin Thurmond's next movie review BreezeJames Madison University's Student Newspaper Volume 84, Issue 54 1 Thursday. April 24, 2008 From the Inside: Getting Down to Business BY AMY PASSAKEni Ihtitmt After whal fell like the most dit ticult semester of their lives, th- 1 BY TIM CHAPMAN members of Key Free Security ean Iht tmit walk away with a sense of ■ccoru plishment. a prestigious a Ward and most notably. $6,ooo. At about ±:'SO in the morning last Friday, an unlikely fig- This team ofsh business mtjoi ure toted a ratty old broom and dustpan through the V.I.P. won the sixth annual ('()B {on Bud lounge of the Rorktnwn Bar and Grill. ness Plan Competition. Sponsored With his hulking 6-foot-2, 240-pound-frame, Lov^H by JMU's College of Business and pears a bit out of place with the cleaning materials. I*t ir» the Executive Ad\isor> Council, tin just another "perk" to being the head of security ,it Harri- competition provides an opportu sonburg's hottest spot on Thursday nights. nit\ to win more than $25,000 in "It's peaceful now at least," JMU senior Drew I.oy says scholarships between each of th after releasing a long sigh. "Cleanup takes awhile, hut it feels top live teams. Nearly 150 poesfl>l like nothing compared to dealing with the people." teams, from over three Mm can be nominated or submit their The people, JMU students, age 21 or older, have left what own proposals for review. -

Seniors Say Goodbye to KDS

The Sun Devils’ Advocate Volume XLI, Number 6 Kent Denver School, 4000 East Quincy Avenue, Englewood, CO 80113 June 4, 2019 Seniors Say Goodbye To KDS Soul band SOUL’D OUT plays “I Want You Back” at Coffee House. Photo by Mika Fisher Student Run Continuation & Crisis in Service Commencement Venezuela Organization Awards See Page 5 See Page 11 See Page 13 Arts & Entertainment Winter. Is. Here. enemy to Winterfell after bending the knee to Bran out of a tower window many seasons ago. by Rachel Wagner warrior Christina Aguilera (thank you, Jona- Slightly awkward. than Van Ness). The northerners are quite con- *Spoilers ahead! You’ve been warned.* Tormund and his Wilding friends take a servative because they want their borders shut quick jaunt to the Least Hearth and find the Alright, “Game of Thrones” fans. Season and sealed. Even after Bran informs everyone White Walkers have beat them there. There is a seven left us with several cliff hangers. Jon that the Night King is about to stroll in with his big Fibonacci-like display of dismembered hu- and Dany were in some kind of relationship, undead army, the Winterfellians are still wary man arms surrounding an undead boy. Cheer- but we found out some disturbing information of their “guests.” A few reunions that are rather ing, right? about their familial relationship. All of the ma- sweet are that of Sansa and Tyrion and Jon and jor camps of people came together in King’s Arya. Some people have complained that this Landing in an attempt to get everyone to fight first episode was disappointing. -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

M Usic , M Oviesand M

Nov.Nov. 3,3, 20052005 Music,M u s i c , MMovieso v i e s anda n d MoreM o r e ‘Saw II’ rips through theaters MUSIC: Neil YYoungoung, GZA and AAshleeshlee Simpson brbringing new music ttoo fanfanss MOVIE: ‘L‘Legendegend of ZZorro’orro’ makes marmark,k, ‘Nor‘Northth CCountry’ountry’ ttouchesouches audiencaudienceses MORE: RReadead fforor yyourour ststomach,omach, plus the lalatesttest enentertainmenttertainment newnewss 2 THE BUZZ the cover of the December-Janu- ary 2006 … Barbara Walters will Contents ary issue of Teen People. Jessica be presenting her “10 Most Fasci- Simpson, 25, a self-proclaimed nating People of 2005.” Some of THE ditz, tells the magazine she went to the infl uential people who made The Inside Buzz therapy during her publicity over- the cut include Kanye West, Sec- 02 I N S I D E load; sister Ashlee opens up about retary of State Condoleezza Rice her recent singing fl ops, like the and even Tom Mesereau, Michael 03 Girls That Rock Series - Part 3 infamous “Saturday Night Live” Jackson’s lawyer. The show will BUZZ lip-synching debacle and the Or- air on Nov. 29 on ABC at 10 p.m. ange Bowl fi asco … 33-year-old … Notable CD releases out Tues- 04 New Movie Reviews actress Gabrielle Union has sepa- day were Santana All That I Am rated from husband, Chris How- … Rammstein Rosenrot [Import] 05 New Movie Reviews ard, a former Jacksonville Jaguar … John Fogerty The Long Road running back. … Mary J. Blige Home: Ultimate John Fogerty 06 Flashback Favorite will receive the VLegend Award Creedence Collection … new By MAHSA KHALILIFAR from Vibe at the 3rd annual awards DVD releases this week include Daily Titan Asst. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ SCRAPBOOK A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2001 by C. Lynn Shaffer B.A., Morehead State University, 1993 M.A., Morehead State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Don Bogen C. Lynn Shaffer Dissertation Abstract This dissertation, a collection of original poetry by C. Lynn Shaffer, consists of three sections, predominantly persona poems in narrative free verse form. One section presents the points of view of different individuals; the other sections are sequences that develop two central characters: a veteran living in modern-day America and the historical figure Secondo Pia, a nineteenth-century Italian lawyer and photographer whose name is not as well known as the image he captured -

Free Monologues for Kids and Teens Pg

© Drama Notebook www.dramanotebook.com Free Monologues for Kids and Teens pg. 1 Copyright 2020 Published in the United States by Drama Notebook www.dramanotebook.com a division of Rumpelstiltskin Press, Portland Oregon USA All rights reserved. While this collection is free for teachers and students to use, it is copyright protected. Any commercial use is strictly prohibited without written permission from the publisher of this work. The monologues may be used in classrooms, performed in competitions, used in auditions, and performed as part of school/educational plays completely royalty- free. Please credit ‘Drama Notebook’ in all forms of performance. For commercial rights or other inquiries, please contact Janea Dahl at [email protected] Quick Copyright FAQ’s You may use these monologues freely with your students. You MAY share this PDF with your students via Google drive, email, or through your password protected teacher web page. You MAY print as many copies as you need for classroom use with your students. Your students MAY perform the monologues for class work, performances and competitions WITHOUT requesting permission, but students must cite the author and “published on Drama Notebook” in their recitation. Neither you nor your students may edit the monologues. You may NOT post the PDF on a web page that is searchable/view-able by the public. You may NOT email the collection to other teachers or educators. Rather, please refer them to Drama Notebook to obtain their own download. ENJOY! © Drama Notebook www.dramanotebook.com Free Monologues for Kids and Teens pg. 2 Free Monologues for Kids and Teens Written by kids and teens! Drama Notebook has created the world’s largest collection of original monologues written by children and teenagers. -

The Echo: February 15, 2013

TAYLOR UNIVERSITY Weekly Edition Women’s basketball gets stuffed at the 3-point line page 12 Celebrating 100 years as Taylor’s News Source Since 1913 1 Volume 100, Issue 15 Friday/Thursday, February 15-February 21, 2013 TheEchoNews.com HEADLINES Million Dollar Marion Café Valley Inc., a baked goods supplier based in Phoenix, Ariz., will be undertaking a multi-million dollar construction project that will lead to hundreds of job opportunities in Marion. Page 3 Roe V. Wade Continued Continue reading from last week about 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, covering the physical, emotional and spiritual complications of abortion. Page 4 Google augments reality Although Google Glass remains shrouded in secrecy, the first developers are now getting their hands on the new device. How long will it be before we’re all wearing phones on our faces? Page 5 Volleyball in Israel Photography by Timothy P. Riethmiller Last month Coach Brittany Smith traveled to Israel to work with Palestinian volleyball teams and coaches. Page 9 Dorm culture forms from ground up Baseball Preview Students will form identity The Trojans will look to improve on last leadership positions for the fall, according pioneer and contribute to the new resi- be a hall retreat at the beginning of the year, season by mixing the new freshmen for new dorm this fall to Dean of Residence Life and Discipleship dence hall’s culture. giving students a common experience and with the experienced upperclassmen. They kicked off their season yesterday Steve Morley. This dorm, like the other residence halls, pride in the place they live. -

Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’;

! ! The ‘Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines’ Tactical Construction of Space by Addie Shrodes A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2012 ! ! ! ! © March 19, 2012 Addie Cherice Shrodes ! ! Acknowledgements I wrote this thesis because of the help of many insightful and inspiring people and professors I have had the pleasure of working with during the past three years. To begin, I am immensely indebted to my thesis adviser, Prof. Gillian White, firstly for her belief in my somewhat-strange project and her continuous encouragement throughout the process of research and writing. My thesis has benefitted enormously from her insightful ideas and analysis of language, poetry and gender, among countless other topics. I also thank Prof. White for her patient and persistent work in reading every page I produced. I am very grateful to Prof. Sara Blair for inspiring and encouraging my interest in literature from my first Introduction to Literature class through my exploration of countercultural productions and theories of space. As my first English professor at Michigan and continual consultant, Prof. Blair suggested that I apply to the Honors program three years ago, and I began English Honors and wrote this particular thesis in a large part because of her. I owe a great deal to Prof. Jennifer Wenzel’s careful and helpful critique of my thesis drafts. I also thank her for her encouragement and humor when the thesis cohort weathered its most chilling deadlines. I am thankful to Prof. Lucy Hartley, Prof. -

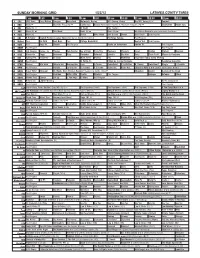

Sunday Morning Grid 1/22/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/22/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Rangers Horseland Motorcycle Racing NFL Champ. Chase The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Hockey Washington Capitals at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Å Countdown Action Spo. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å We Have a Dream Inspirational black Americans. 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX R Schuller English Premier League Soccer Arsenal vs. Manchester United. Fox News Sunday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Tm Wrld Best Buys Paid College Basketball Best of L.A. Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Hey Kids Taste Chefs Field Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid McMahon Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Am Me LGBTQ+ Resource Guide V.1 2 This LGBTQ+ Resource Guide

“I Am Me: Understanding the Intersections of Gender, Sexuality, and Identity” is an educational training video that explores the challenges our lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, etc. (LGBTQ+) young people face and how adults can be supportive allies. The video begins with the concepts of gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation and then explores the challenges that LGBTQ+ youth face through personal stories from young people and adult advocates. The video ends with youth sharing how they need to be supported and a checklist on how to participate in acts of allyship for LGBTQ+ youth. To watch the full I Am Me video, go here: http://www.nmsoc.org/cocvideos.html This LGBTQ+ training video and resource guide were created in 2016 by the New Mexico Communities of Care in partnership with 12FPS (12fps.com) and Prevention at Play (www.preventionatplay.com). New Mexico Communities of Care’s primary objective is to keep youth, who have a serious mental health diagnosis, with their family and in their community getting the care that they need. This video is one of many efforts to ensure that adults, working with youth, have the knowledge and skills they need to support youth in all areas of service. Our hope is that this video will positively impact adults and improve outcomes for youth in any arena (schools, community organizations, communities of faith, families, etc.) working with or connected to LGBTQ+ young people. To learn more about Communities of Care, visit www.nmsoc.org/. I Am Me LGBTQ+ Resource Guide v.1 2 This LGBTQ+ Resource Guide This resource guide is a companion to the I Am Me video. -

Writing As an Expression of Self & in Relation to Others Meg Stentz D

WRITING AS AN EXPRESSION OF SELF & IN RELATION TO OTHERS 1 “I Am Who I Want To Be Not Who You Want Me To Be”: Writing as an Expression of Self & In Relation to Others Meg Stentz Dr. Beverly Moss The Ohio State University WRITING AS AN EXPRESSION OF SELF & IN RELATION TO OTHERS 2 Abstract By adding a writing component to an existing model of structured support group, Stentz examines the way four ninth grade girls use writing to define their own identities and their relationships with one another. Her research centers around questions about how writing is received in the group: how does writing further the goals of an organization which seeks to promote connection between girls? And, how do the girls use writing, as opposed to speaking, to articulate their identities? Stentz found that girls’ use of writing provides an opportunity to put forward a vision of the self that the girls do not access in speech. Furthermore, the girls use writing—both the words and the act itself—to demonstrate and strengthen their friendships and allegiances within the group. Stentz analyzed the girls’ writings and speaking in the support group to reach these conclusions, as well as interviewing each girl at the end of the project. Stentz’s project indicates the usefulness of writing in a group that seeks to promote connection between its members and may be of interest to individuals who work with groups, particularly groups of teenaged girls. WRITING AS AN EXPRESSION OF SELF & IN RELATION TO OTHERS 3 Chapter One: A Study With not For Girls Introduction At the age of 19, in a fervor of academic inferiority I signed up for History of Critical Theory, one of the densest courses my English department offers. -

Lyrics: Rise Shine #Woke

LYRIC BOOK alphabetrockers.com Welcome Rockstars! We made this album for YOU. We made it for you to feel proud of who you are. We made Contents it so you could learn to be a super friend for someone else. We made it to remind us ALL of 1 The Nitro how this world is ours to change. We get to take 2 Turn On The Lights good care of each other. We can notice when 3 Rise things are not fair and say, “Wait. Stop! We can 4 Questions (Interlude) do better.” Let’s all do better. 5 I'm Proud This album reminds us to RISE, like the 6 My Light sun each morning. It reminds us to SHINE our 7 Shine light and lift each other up. It reminds us to 8 On the Corner (Interlude) be WOKE by waking up to injustice and doing 9 What Are You? everything we can to stop it. This music helps 10 Walls us to imagine a world where EVERYONE feels 11 Stand Up for You safe and loved. 12y Swa Imagine that you have the power to make 13 ACTIVITY GUIDE people around you feel welcome and know 14 ABOUT US they belong. You do! Imagine that you have the courage to speak out and stand up for justice. 15 ALBUM CREDITS You do! Imagine a world where we all feel free to be our true selves. This is the world we are making, rockstars! With love and hip hop, The Alphabet Rockers Crew ©π2017 School Time Music LLC | alphabetrockers.com | @alphabetrockers | [email protected] T he Nitro © School TIme Music LLC Written by Kaitlin McGaw, Tommy Shepherd, Jerry Lordan [sample of Sugarhill Gang “Apache (Jump on It)”] Whatcha gonna do when the rockers come through? Just wave 'em, wave 'em, wave 'em in the air I’m gonna have some fun! Wave 'em, wave 'em - like you just don’t care What do you consider fun? Bring it down to the floor, Fun, natural fun! Stomp it out you want some more.