Shakespeare's Tremor the Real Mystery Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iago and His Motives Under Modern Eyes Amany Abdelrazik

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS) Vol-3, Issue-4, Jul - Aug, 2018 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.3.4.28 ISSN: 2456-7620 Iago and His Motives under Modern Eyes Amany Abdelrazik PHD Researcher - Freie Universität Berlin, Germany Abstract—Shakespeare's plays depict the turn from the to the issues which appear in Othello have greatly pre-modern era with its traditional values and mores into changed between Shakespeare’s time and our the modern approach towards life and individuals. These own...” (Holloway, 1961, p. 155), I am encouraged plays deal with specific questions that were significant in to re-read Iago´s behaviour in light of modern Shakespeare's time and his cultural contexts, such as the thought that could satisfy the modern individual mores and meanings of Christian values in the society, understanding without taking the text out of its the rise of humanism, monarchy and questions related to original context. the economy. Nonetheless, Shakespeare´s questions on Rereading Iago´s behaviour through the religious values and the modern individual seem to be modern lens, I am going to contradict relevant today, in particular, with the recent post-modern Coleridge´s claim of Iago´s “motiveless discussions on the limits of secular rational modernity malignity” through trying out two and a return to a new condition of believing in arguments. Firstly, I argue that Iago´s contemporary societies. Taking the character of Iago as motives lurked inside his own narcissist my reference point, I shall attempt to reread Iago´s character that believed deeply in the actions and psyche in light of a critique of the narcissist individual’s willpower. -

The Elusive Ensign: Towards a “ Grammar” of Iago's Motives

The elusive ensign: towards a “grammar” of Iago’s motives Keith Gregor UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA Of all Iago’s gestures few are more unsettling than his defiant final words to his captors: “De- mand me nothing; what you know, you know: /From this time forth I never will speak word” (5. 2. 300-1)1. And so his part in Othello concludes, the real reasons for his “fault” being left for his torturers’ ears —and to the audience’s imagination. No one would “demand” him anything, were it not for that endless dialogue between work and interpreter which has been the hallmark of post- early modern critical practice. Just as art is seen to begin at the edges of the author’s “existential reality”, so the disappearance of the player is regarded as the condition of his re-birth as a character. In the case of Iago, this re-birth tends to hinge on the recovery of that most elusive element: the ensign’s motives. The concept of character would then seem inseparable from an account of motivation. After all, both concepts emerge at the same historical moment. Elizabethans, it seems, explained action in terms of a taxonomy of humours or the equally venerable dichotomy of virtue and vice (Scragg 1968). The “motiveless malignity” which Coleridge found lurking in Iago would mean little to an audience which, as Bradbrook noted, “did not expect every character to produce one rational explanation for every given action” (1983, 59-60). Iago’s silence would thus be an adequate response for an audience which failed, or simply refused, to see beyond the deed. -

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE The Maltese Falcon introduced a new detective – Sam Spade – whose physical aspects (shades of his conversation with Stein) now approximated Hammett’s. The novel also originated a fresh narrative direction. The Op related his own stories and investigations, lodging his idiosyncrasies, omissions and intuitions at the core of Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. For The Maltese Falcon Hammett shifted to a neutral, but chilling third-person narration that consistently monitors Spade from the outside – often insouciantly as a ‘blond satan’ or a smiling ‘wolfish’ cur – but never ventures anywhere Spade does not go or witnesses anything Spade doesn’t see. This cold-eyed yet restricted angle prolongs the suspense; when Spade learns of Archer’s murder we hear only his end of the phone call – ‘Hello . Yes, speaking . Dead? . Yes . Fifteen minutes. Thanks.’ The name of the deceased stays concealed with the detective until he enters the crime scene and views his partner’s corpse. Never disclosing what Spade is feeling and thinking, Hammett positions indeterminacy as an implicit moral stance. By screening the reader from his gumshoe’s inner life, he pulls us into Spade’s ambiguous world. As Spade consoles Brigid O’Shaughnessy, ‘It’s not always easy to know what to do.’ The worldly cynicism (Brigid and Spade ‘maybe’ love each other, Spade says), the coruscating images of compulsive materialism (Spade no less than the iconic Falcon), the strings of point-blank maxims (Spade’s elegant ‘I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble’): Sam Spade was Dashiell Hammett’s most appealing and enduring creation, even before Bogart indelibly limned him for the 1941 film. -

A Short History of Occupational Disease: 2. Asbestos, Chemicals

Ulster Med J 2021;90(1):32-34 Medical History A SHORT HISTORY OF OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE: 2. ASBESTOS, CHEMICALS, RADIUM AND BEYOND Petts D, Wren MWD, Nation BR, Guthrie G, Kyle B, Peters L, Mortlock S, Clarke S, Burt C. ABSTRACT OCCUPATIONAL CANCER Historically, the weighing out and manipulation of dangerous Towards the end of the 18th century, a possible causal link chemicals frequently occurred without adequate protection between chemicals and cancer was reported by two London from inhalation or accidental ingestion. The use of gloves, surgeons. In 1761, John Hill reported an association between eye protection using goggles, masks or visors was scant. snuff, a tobacco product, and nasopharyngeal cancer, From Canary Girls and chimney sweeps to miners, stone and, in 1775, Percival Pott described a high incidence of cutters and silo fillers, these are classic exemplars of the subtle scrotal cancer in chimney sweeps. Pott, a surgeon at St (and in some cases not so subtle) effects that substances, Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, published his findings,6 environments and practices can have on individual health. which he attributed to contamination with soot. This excellent INTRODUCTION epidemiological study is considered to be the first report of a potential carcinogen. Pott’s work led to the foundation of It has been known for many centuries that certain diseases occupational medicine and to the Chimney Sweep Act of were associated with particular occupations (i.e. wool- 1788. In 1895, Ludwig Reyn reported that aromatic amines sorters disease in the textile industry, cowpox in milk maids used in certain dye industries in Germany were linked and respiratory problems in miners and stone workers). -

Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, a Case Study

Katie Walsh Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, A Case Study Abstract William Powell became a star in the 1930s due to his unique brand of suave charm and witty humor—a quality that could only be expressed with the advent of sound film, and one that took him from mid-level player typecast as a villain, to one of the most popular romantic comedy leads of the era. His charm lay in the nonchalant sophistication that came naturally to Powell and that he displayed with ease both on screen and off. He was exemplary of the success of the new kind of star that came into their own during the transition to sound: sharp- or silver-tongued actors who were charming because of their way with words and not because of their silver screen faces. Powell also exercised a great deal of control over his publicity and star image, which is best examined during his short and failed tenure as a Warner Bros. during the advent of his rise to stardom. Despite holding a great amount of power in his billing and creative control, Powell was given a parade of cookie-cutter dangerous playboy roles, and the terms of his contract and salary were constantly in flux over the three years he spent there. With the help of his agent Myron Selznick, Powell was able to navigate between three studios in only a matter of a few years, in search of the perfect fit for his natural abilities as an actor. This experimentation with star image and publicity marked the period of the early 1930s in Hollywood, as studios dealt with the quickly evolving art and technological form, industrial and business practices, and a shifting cultural and moral landscape. -

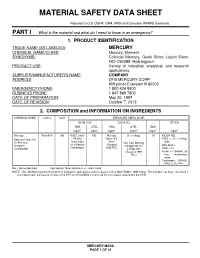

Material Safety Data Sheet

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Prepared to U.S. OSHA, CMA, ANSI and Canadian WHMIS Standards PART I What is the material and what do I need to know in an emergency? 1. PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION TRADE NAME (AS LABELED) : MERCURY CHEMICAL NAME/CLASS : Mercury; Element SYNONYMS: Colloidal Mercury, Quick Silver; Liquid Silver; NCI-C60399; Hydrargyrum PRODUCT USE : Variety of industrial, analytical, and research applications. SUPPLIER/MANUFACTURER'S NAME : COMPANY ADDRESS : DFG MERCURY CORP 909 pitner Evanston Ill 60202 EMERGENCY PHONE : 1 800 424 9300 BUSINESS PHONE : 1 847 869 7800 DATE OF PREPARATION : May 20, 1997 DATE OF REVISION : October 7, 2013 2. COMPOSITION and INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS CHEMICAL NAME CAS # %w/w EXPOSURE LIMITS IN AIR ACGIH-TLV OSHA-PEL OTHER TWA STEL TWA STEL IDLH mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 Mercury 7439-97-6 100 0.025, (skin) NE Mercury 0.1 (ceiling) 10 NIOSH REL: Exposure limits are A4 (Not Vapor: 0.5, STEL = 0.1 (ceiling, for Mercury, Classifiable Skin; Non-alkyl Mercury skin) Inorganic as a Human (Vacated Compounds: 0.1 DFG MAKs: Compounds Carcinogen) 1989 PEL) Ceiling, skin TWA = 0.1 (Vacated 1989 PEAK = 10 •MAK 30 PEL) min., momentary value Carcinogen: EPA-D; IARC-3, TLV-A4 NE = Not Established. See Section 16 for Definitions of Terms Used. NOTE: ALL WHMIS required information is included in appropriate sections based on the ANSI Z400.1-1998 format. This product has been classified in accordance with the hazard criteria of the CPR and the MSDS contains all the information required by the CPR. -

Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <Em>Othello</Em>

Marquette University From the SelectedWorks of Sarah E. Thompson 2012 "I Am No Strumpet": Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <em>Othello</em> Sarah E. Thompson, Marquette University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/sarah_thompson/1/ 1 Sarah Thompson English 6220 December 12, 2012 “I Am No Strumpet”: Bianca and Cassio’s Relationship in Othello Throughout the critical history of Shakespeare’s Othello, audiences and critics alike have identified love and sexuality as major themes of the play. Indeed, there are many who would argue that the play as a whole is an examination of heterosexual relationships, with all the concerns, such as sexual anxieties, gender inequalities, and emotional struggles that accompany this subject. Discussions of Othello’s portrayal of the relationships between men and women integrate any number of other facets of literary study, such as the psychological factors that shape the relationships of Othello and Desdemona or Iago and Emilia, or the cultural expectations for gender and marriage during the Renaissance, and how these expectations are both upheld and critiqued in Othello, or how the genre elements of sex, or love, tragedies influence the play’s action and the audience’s expectations for the play. Many critics who examine the married relationships focus on the feminine roles that Desdemona and Emilia fill or challenge, while others study the masculine perspectives of these relationships, and seek to explore what prompts Iago’s seeming “hatred of his wife and all women,”1 or Othello’s obsession with Desdemona’s sexuality, and his self-doubts, frequently linked to his age and racial status, about his ability to satisfy her in their relationship. -

Complete Issue (PDF)

Abstracts Eliminating Occupational Disease: areas in the country. The study studied 40 small scale industries, and collected 40 water samples (potable) for cyanide and mer- Translating Research into Action cury which are used in mining. Questionnaire-guided interviews EPICOH 2017 and work analysis covering mining practices and risk exposures were conducted, as well as chemical analysis through gas chro- 28–31 August 2017, Edinburgh, UK matography. Results of the study showed unsafe conditions in the industries such as risk of fall during erection and dismantling of scaffolds, guard rails were not provided in scaffoldings, man- Poster Presentation ual extraction of underground ores, use of explosives, poor visi- bility in looking for ores to take out to surface, exposure to Pesticides noise from explosives, and to dust from the demolished struc- tures. Mine waste was drained into soil or ground and/or rivers and streams. The most common health problems among miners 0007 ASSESSMENT OF PESTICIDE EXPOSURE AND were hypertension (62%), followed by hypertensive cardiovascu- OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH OF FARMERS IN lar disease due to left wall ischemia (14%). Health symptoms THE PHILIPPINES such as dermatitis, and peripheral neuropathy were noted and Jinky Leilanie Lu. National Institutes of Health, Institute of Health Policy and Development these can be considered as manifestations of chronic cyanide poi- Studies, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, The Philippines soning, further, aggravated by improper use of protective equip- ment. For the environmental samples of potable water, 88% and 10.1136/oemed-2017-104636.1 98% were positive with mercury and cyanide respectively. About 52% of drinking water samples exceeded the TLV for mercury Aims This is a study conducted among 534 farmers in an while 2% exceeded the TLV for cyanide. -

At Work in the World

Perspectives in Medical Humanities At Work in the World Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health Edited by Paul D. Blanc, MD and Brian Dolan, PhD Page Intentionally Left Blank At Work in the World Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the History of Occupational and Environmental Health Perspectives in Medical Humanities Perspectives in Medical Humanities publishes scholarship produced or reviewed under the auspices of the University of California Medical Humanities Consortium, a multi-campus collaborative of faculty, students and trainees in the humanities, medi- cine, and health sciences. Our series invites scholars from the humanities and health care professions to share narratives and analysis on health, healing, and the contexts of our beliefs and practices that impact biomedical inquiry. General Editor Brian Dolan, PhD, Professor of Social Medicine and Medical Humanities, University of California, San Francisco (ucsf) Recent Monograph Titles Health Citizenship: Essays in Social Medicine and Biomedical Politics By Dorothy Porter (Fall 2011) Paths to Innovation: Discovering Recombinant DNA, Oncogenes and Prions, In One Medical School, Over One Decade By Henry Bourne (Fall 2011) The Remarkables: Endocrine Abnormalities in Art By Carol Clark and Orlo Clark (Winter 2011) Clowns and Jokers Can Heal Us: Comedy and Medicine By Albert Howard Carter iii (Winter 2011) www.medicalhumanities.ucsf.edu [email protected] This series is made possible by the generous support of the Dean of the School of Medicine at ucsf, the Center for Humanities and Health Sciences at ucsf, and a Multi-Campus Research Program grant from the University of California Office of the President. -

Mercury Study Report to Congress

United States EPA-452/R-97-007 Environmental Protection December 1997 Agency Air Mercury Study Report to Congress Volume V: Health Effects of Mercury and Mercury Compounds Office of Air Quality Planning & Standards and Office of Research and Development c7o032-1-1 MERCURY STUDY REPORT TO CONGRESS VOLUME V: HEALTH EFFECTS OF MERCURY AND MERCURY COMPOUNDS December 1997 Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards and Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency TABLE OF CONTENTS Page U.S. EPA AUTHORS ............................................................... iv SCIENTIFIC PEER REVIEWERS ...................................................... v WORK GROUP AND U.S. EPA/ORD REVIEWERS ......................................viii LIST OF TABLES...................................................................ix LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................. xii LIST OF SYMBOLS, UNITS AND ACRONYMS ........................................xiii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................... ES-1 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................1-1 2. TOXICOKINETICS ..........................................................2-1 2.1 Absorption ...........................................................2-1 2.1.1 Elemental Mercury ..............................................2-1 2.1.2 Inorganic Mercury ..............................................2-2 2.1.3 Methylmercury .................................................2-3 2.2 Distribution -

3.5 3.6 Rangan Metals Metalloids New Orleans

Metals/Metalloids Metals and Metalloids Cyrus Rangan MD, FAAP, ACMT Los Angeles County Department of Public Health California Poison Control System Childrens Hospital Los Angeles 1 Treatment of Metal Poisoning Old School Approaches “The treatment of acute [insert metal here]-poisoning consists in the evacuation of the stomach, if necessary, the exhibition of the sulphate of sodium or of magnesium, and the meeting of the indications as they arise. The Epsom and Glauber’s salts act as chemical antidotes, by precipitating the insoluble sulphate of [insert metal here], and also, if in excess, empty the bowel of the compound formed. To allay gastrointestinal irritation, albuminous drinks should be given and opium freely exhibited…” Wood, HC: Therapeutics Materia Medica and Toxicology, 1879 2 Treatment of Metal Poisoning Old School Approaches “If possible, the rapid administration of 2 oz. (6-7 heaping teaspoonfuls) of Magnesium sulfate (Epsom Salts) or Sodium sulfate (Glauber’s Salt) in plenty of water. Alum (aluminum potassium sulfate) will also be useful in 4 gm (60 gr.) doses (dissolved) repeated. Very dilute Sulfuric acid may be employed (30 cc of a 10 % solution diluted to 1 quart). All soluble sulfates precipitate [metal] as an insoluble sulfate…” Lucas, GW: The Symptoms and Treatment of Acute Poisoning; 1953 3 1 Metals/Metalloids Overview of Metals • Iron • Lead • Arsenic • Mercury • … a whole bunch of other ones 4 What’s a Metal? What’s a Metalloid? 5 Iron Poisoning Introduction • Essential for normal tissue and organ function • In toxic doses, iron salts (ferrous sulfate, fumarate or gluconate) cause corrosive gastrointestinal effects followed by hypotension, metabolic acidosis, and multisystem failure. -

Othello As an Enigma to Himself: a Jungian Approach to Character Analysis Eric Iliff Eastern Washington University

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2013 Othello as an enigma to himself: a Jungian approach to character analysis Eric Iliff Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Iliff, Eric, "Othello as an enigma to himself: a Jungian approach to character analysis" (2013). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 138. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/138 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Othello as an Enigma to Himself: A Jungian Approach to Character Analysis A Thesis Presented to Eastern Washington University Cheney, Wa In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts (Literary Studies) By Eric Iliff Spring 2013 I l i f f ii THESIS OF ERIC ILIFF APPROVED BY Dr. Grant Smith, Chair, Graduate Study Committee Date Dr. Philip Weller, Graduate Study Committee Date Dr. Martha Raske, Graduate Study Committee Date I l i f f iii Table of Contents Introductio n .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Procedure .....................................................................................................................................................