At Work in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altria.Com/Proxy

6601 West Broad Street Richmond, Virginia 23230 Dear Fellow Shareholder: It is my pleasure to invite you to join us at the 2016 Annual Meeting of Shareholders of Altria Group, Inc. to be held on Thursday, May 19, 2016 at 9:00 a.m., Eastern Time, at the Greater Richmond Convention Center, 403 North 3rd Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219. At this year’s meeting, we will vote on the election of 11 directors, the ratification of the selection of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP as the Company’s independent registered public accounting firm and, if properly presented, two shareholder proposals. We will also conduct a non-binding advisory vote to approve the compensation of the Company’s named executive officers. There also will be a report on the Company’s business, and shareholders will have an opportunity to ask questions. To attend the meeting, an admission ticket and government-issued photo identification are required. To request an admission ticket, please follow the instructions on page 9 in response to Question 16. One immediate family member who is 21 years of age or older may accompany a shareholder as a guest. We use the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule that allows companies to furnish proxy materials to their shareholders over the Internet. We believe this expedites shareholders receiving proxy materials, lowers costs and conserves natural resources. We thus are mailing to many shareholders a Notice of Internet Availability of Proxy Materials, rather than a paper copy of the Proxy Statement and our Annual Report on Form 10-K for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2015. -

Sept. 9–15, 2019 Guernsey County FAIR Guernseycountyfair.Org Darryl Watson, Owner/Manager P.O

172ND Sept. 9–15, 2019 Guernsey County FAIR guernseycountyfair.org Darryl Watson, Owner/Manager P.O. Box 166, New Concord, OH 43762 Office: (740) 425-3611 Fax: (740) 425-3612 Cell: (740) 624-9335 Find us on e-mail: [email protected] Facebook for an Updated 315 South Gardner St Market Report Barnesville, OH 43713 Sale Every Saturday at 12:30 p.m. Consignments are welcome! Good Luck to All 4-H & FFA Exhibitors SPECIAL SALES IN ADDITION TO OUR REGULAR SALES SEPT 15TH & OCT. 13TH 10 AM Graded Feeder Calf Sales sponsored by The Barnesville Feeder Calf Association Successful Year!!! NOV. 6TH • 7 PM Cow Sale sponsored by Ohio Valley Cattleman’s Association Sale 4 068507 CJ-1 GUERNSEYGUERNSEYGuern Co1 Fair3 FaiR1 Fair1 Welcome to the Fair! It’s time again already for the Guernsey County your schedule� Fair, the 172nd edition� Again this year we have some As always the heart and soul of the fair lies with the exciting new things to offer as well as tried and true Junior Fair exhibits and exhibitors� This is the place entertainment� where generations of hard working families come Many of you asked for “Big” entertainment and we together for the week they look forward to most� listened, even to the extent of offering a poll which was 2018 was a bit of a challenge with the weather we a huge success� battled through, but that is behind us and we look So on Wednesday September 11 we welcome Craig forward to an entertaining week� Morgan to the county fair stage� From Tractor and Truck pulls, Demo Derby, Rodeo Opening for Morgan will be another Nashville -

Altria Group, Inc. Annual Report

ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company | Inc. Altria Group, Report 2020 Annual an Altria Company From tobacco company To tobacco harm reduction company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company ananan Altria Altria Altria Company Company Company an Altria Company Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. | 6601 W. Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23230-1723 | altria.com 2020 Annual Report Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Altria 2020 Annual Report | Andra Design Studio | Tuesday, February 2, 2021 9:00am Dear Fellow Shareholders March 11, 2021 Altria delivered outstanding results in 2020 and made steady progress toward our 10-Year Vision (Vision) despite the many challenges we faced. Our tobacco businesses were resilient and our employees rose to the challenge together to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, political and social unrest, and an uncertain economic outlook. Altria’s full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share (EPS) grew 3.6% driven primarily by strong performance of our tobacco businesses, and we increased our dividend for the 55th time in 51 years. Moving Beyond Smoking: Progress Toward Our 10-Year Vision Building on our long history of industry leadership, our Vision is to responsibly lead the transition of adult smokers to a non-combustible future. Altria is Moving Beyond Smoking and leading the way by taking actions to transition millions to potentially less harmful choices — a substantial opportunity for adult tobacco consumers 21+, Altria’s businesses, and society. To achieve our Vision, we are building a deep understanding of evolving adult tobacco consumer preferences, expanding awareness and availability of our non-combustible portfolio, and, when authorized by FDA, educating adult smokers about the benefits of switching to alternative products. -

STATE of OKLAHOMA OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PRACTICE ACT Title 59 O.S., Sections 888.1 - 888.16

Amended: November 1, 2019 STATE OF OKLAHOMA OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PRACTICE ACT Title 59 O.S., Sections 888.1 - 888.16 INDEX 888.1. Short Title 888.2 Purpose 888.3. Definitions 888.4. License required - Application of Act 888.5. Practices, services and activities not prohibited 888.6. Application for license - information required 888.7. Application for license - form - examination and reexamination 888.8. Waiver of examination, education or experience requirement 888.9. Denial, refusal, suspension, revocation, censure, probation and reinstatement of license 888.10. Renewal of license - continuing education 888.11. Fees 888.12. Oklahoma Occupational Therapy Advisory Committee - creation - membership - term - vacancies - removal - liability 888.13. Oklahoma Occupational Therapy Advisory Committee - officers - meetings - rules - records - expenses 888.14. Powers and duties of Committee 888.15. Titles and abbreviations - misrepresentation - penalties -1- 888.1. Short title This act shall be known and cited as the "Occupational Therapy Practice Act". 888.2. Purpose In order to safeguard the public health, safety and welfare, to protect the public from being misled by incompetent and un-authorized persons, to assure the highest degree of professional conduct on the part of occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants, and to assure the availability of occupational therapy services of high quality to persons in need of such services, it is the purpose of this act to provide for the regulation of persons offering occupational therapy -

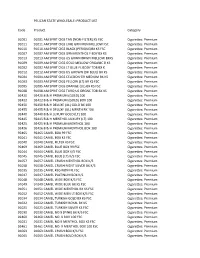

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

WFOT ANNOUNCEMENTS & DELEGATE UPDATE May 2014

WFOT ANNOUNCEMENTS & DELEGATE UPDATE May 2014 WFOT BULLETIN – MAY 2014 This edition addresses Assistive Technology and Information Technology. Take a trip around the world with OT authors from Austria, Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hong Kong, Latvia, Netherlands, Romania, Sweden, Singapore, United Kingdom, USA AOTA CONFERENCE – BALTIMORE, MD – April 2014 – PLETHORA OF INTERNATIONAL EVENTS: More than 60 international and cross cultural sessions addressed topics like: service learning, fieldwork, occupational justice, human rights, refugees, cultural fluidity, disaster response, assistive technologies, OT Education in under resourced areas, and special populations such as women with obstetric fistulas. 16th WORLD CONGRESS OF OT - YOKOHAMA, JAPAN - June 18-21, 2014 “SHARING TRADITIONS, CREATING FUTURES” REGISTER: http://www.wfot.org/wfot2014/eng/index.html STUDENTS: WOW - registration is only $100 for the four day conference! FELLOW TRAVELERS: http://otconnections.aota.org/more_groups/wfot_congress_2014_japan_preparations_and_reflections/default.aspx HELPING: Donate: http://www.wfot.org/wfot2014/eng/contents/donation.html SPONSORSHIP & EXHIBITING: http://www.wfot.org/wfot2014/eng/contents/sponsor.html PROMOTING: WFOT resources & media pack: http://www.wfot.org/ResourceCentre.aspx WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO) INVITES OCCUPATIONAL THERAPISTS TO JOIN THE GLOBAL CLINICAL PRACTICE NETWORK FOR ICD-11 MENTAL AND BEHAVIOURAL DISORDERS Dear Colleague: The World Health Organization’s Department of Mental Health and Substance -

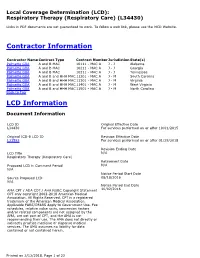

Local Coverage Determination for Respiratory Therapy

Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Respiratory Therapy (Respiratory Care) (L34430) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information Contractor Name Contract Type Contract Number Jurisdiction State(s) Palmetto GBA A and B MAC 10111 - MAC A J - J Alabama Palmetto GBA A and B MAC 10211 - MAC A J - J Georgia Palmetto GBA A and B MAC 10311 - MAC A J - J Tennessee Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11201 - MAC A J - M South Carolina Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11301 - MAC A J - M Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11401 - MAC A J - M West Virginia Palmetto GBA A and B and HHH MAC 11501 - MAC A J - M North Carolina Back to Top LCD Information Document Information LCD ID Original Effective Date L34430 For services performed on or after 10/01/2015 Original ICD-9 LCD ID Revision Effective Date L31593 For services performed on or after 01/29/2018 Revision Ending Date LCD Title N/A Respiratory Therapy (Respiratory Care) Retirement Date Proposed LCD in Comment Period N/A N/A Notice Period Start Date Source Proposed LCD 08/18/2016 N/A Notice Period End Date AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement 10/02/2016 CPT only copyright 2002-2018 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Applicable FARS/DFARS Apply to Government Use. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT, and the AMA is not recommending their use. -

A Short History of Occupational Disease: 2. Asbestos, Chemicals

Ulster Med J 2021;90(1):32-34 Medical History A SHORT HISTORY OF OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE: 2. ASBESTOS, CHEMICALS, RADIUM AND BEYOND Petts D, Wren MWD, Nation BR, Guthrie G, Kyle B, Peters L, Mortlock S, Clarke S, Burt C. ABSTRACT OCCUPATIONAL CANCER Historically, the weighing out and manipulation of dangerous Towards the end of the 18th century, a possible causal link chemicals frequently occurred without adequate protection between chemicals and cancer was reported by two London from inhalation or accidental ingestion. The use of gloves, surgeons. In 1761, John Hill reported an association between eye protection using goggles, masks or visors was scant. snuff, a tobacco product, and nasopharyngeal cancer, From Canary Girls and chimney sweeps to miners, stone and, in 1775, Percival Pott described a high incidence of cutters and silo fillers, these are classic exemplars of the subtle scrotal cancer in chimney sweeps. Pott, a surgeon at St (and in some cases not so subtle) effects that substances, Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, published his findings,6 environments and practices can have on individual health. which he attributed to contamination with soot. This excellent INTRODUCTION epidemiological study is considered to be the first report of a potential carcinogen. Pott’s work led to the foundation of It has been known for many centuries that certain diseases occupational medicine and to the Chimney Sweep Act of were associated with particular occupations (i.e. wool- 1788. In 1895, Ludwig Reyn reported that aromatic amines sorters disease in the textile industry, cowpox in milk maids used in certain dye industries in Germany were linked and respiratory problems in miners and stone workers). -

Alameda County Tobacco Retailer License & Flavored Tobacco Training

ALAMEDA COUNTY TOBACCO RETAILER LICENSE & FLAVORED TOBACCO PRESENTATION 7/29/20 Providing Education and Support to Tobacco Retailers in Alameda County Agenda ❑ Welcome/Introductions ❑ Zoom Housekeeping ❑ Why Tobacco Retail Regulations? ❑ Alameda County’s Tobacco Retail Licensing Ordinance ❑ Restricted Tobacco Products ❑ Questionable Products ❑ Tobacco Retailer License Application Process ❑ Q & A WHY TOBACCO RETAIL REGULATIONS? Flavored Tobacco Hooks Kids Over 90% of adult smokers started before age 18 Flavored tobacco initiates youth tobacco use 4 out of 5 youth smokers started with a flavored product Adolescents are more likely than adults to use flavored e-cigs Fruit and candy flavors are designed to appeal to youth users by masking the harsh taste of tobacco Strong Tobacco Retail Licensing ordinances are effective at decreasing youth tobacco sales rates ALAMEDA COUNTY’S TOBACCO RETAILER LICENSING (TRL) ORDINANCE Overview of Adopted TRL Ordinance Purpose is to reduce youth access to tobacco, and to limit negative public health effects of tobacco use. Requires businesses in Unincorporated Alameda County that sell tobacco to obtain a local license annually to sell tobacco. Provides enforcement mechanism; holds retailers accountable to comply with local requirements, as well as state and federal tobacco laws. Overview of Adopted TRL Ordinance TRL ordinance adopted by BOS on January 14, 2020 Electronic Smoking Devices adopted by BOS on March 10, 2020 Retailers obtain TRL by August 7, 2020 Enforcement of both laws begin: September -

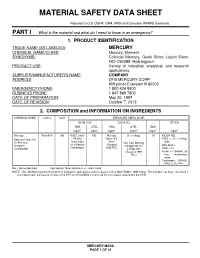

Material Safety Data Sheet

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Prepared to U.S. OSHA, CMA, ANSI and Canadian WHMIS Standards PART I What is the material and what do I need to know in an emergency? 1. PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION TRADE NAME (AS LABELED) : MERCURY CHEMICAL NAME/CLASS : Mercury; Element SYNONYMS: Colloidal Mercury, Quick Silver; Liquid Silver; NCI-C60399; Hydrargyrum PRODUCT USE : Variety of industrial, analytical, and research applications. SUPPLIER/MANUFACTURER'S NAME : COMPANY ADDRESS : DFG MERCURY CORP 909 pitner Evanston Ill 60202 EMERGENCY PHONE : 1 800 424 9300 BUSINESS PHONE : 1 847 869 7800 DATE OF PREPARATION : May 20, 1997 DATE OF REVISION : October 7, 2013 2. COMPOSITION and INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS CHEMICAL NAME CAS # %w/w EXPOSURE LIMITS IN AIR ACGIH-TLV OSHA-PEL OTHER TWA STEL TWA STEL IDLH mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 mg/m 3 Mercury 7439-97-6 100 0.025, (skin) NE Mercury 0.1 (ceiling) 10 NIOSH REL: Exposure limits are A4 (Not Vapor: 0.5, STEL = 0.1 (ceiling, for Mercury, Classifiable Skin; Non-alkyl Mercury skin) Inorganic as a Human (Vacated Compounds: 0.1 DFG MAKs: Compounds Carcinogen) 1989 PEL) Ceiling, skin TWA = 0.1 (Vacated 1989 PEAK = 10 •MAK 30 PEL) min., momentary value Carcinogen: EPA-D; IARC-3, TLV-A4 NE = Not Established. See Section 16 for Definitions of Terms Used. NOTE: ALL WHMIS required information is included in appropriate sections based on the ANSI Z400.1-1998 format. This product has been classified in accordance with the hazard criteria of the CPR and the MSDS contains all the information required by the CPR. -

Complete Issue (PDF)

Abstracts Eliminating Occupational Disease: areas in the country. The study studied 40 small scale industries, and collected 40 water samples (potable) for cyanide and mer- Translating Research into Action cury which are used in mining. Questionnaire-guided interviews EPICOH 2017 and work analysis covering mining practices and risk exposures were conducted, as well as chemical analysis through gas chro- 28–31 August 2017, Edinburgh, UK matography. Results of the study showed unsafe conditions in the industries such as risk of fall during erection and dismantling of scaffolds, guard rails were not provided in scaffoldings, man- Poster Presentation ual extraction of underground ores, use of explosives, poor visi- bility in looking for ores to take out to surface, exposure to Pesticides noise from explosives, and to dust from the demolished struc- tures. Mine waste was drained into soil or ground and/or rivers and streams. The most common health problems among miners 0007 ASSESSMENT OF PESTICIDE EXPOSURE AND were hypertension (62%), followed by hypertensive cardiovascu- OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH OF FARMERS IN lar disease due to left wall ischemia (14%). Health symptoms THE PHILIPPINES such as dermatitis, and peripheral neuropathy were noted and Jinky Leilanie Lu. National Institutes of Health, Institute of Health Policy and Development these can be considered as manifestations of chronic cyanide poi- Studies, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, The Philippines soning, further, aggravated by improper use of protective equip- ment. For the environmental samples of potable water, 88% and 10.1136/oemed-2017-104636.1 98% were positive with mercury and cyanide respectively. About 52% of drinking water samples exceeded the TLV for mercury Aims This is a study conducted among 534 farmers in an while 2% exceeded the TLV for cyanide. -

Your Career in Occupational Therapy: Workforce Trends In

Resources for students from The American Occupational Therapy Association Your career in Occupational Therapy he demand for occupational therapy services is Workforce Trends strong. The U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau Tof Labor Statistics (BLS) projected employment of occupational therapists to increase by 26% and of in Occupational occupational therapy assistants to increase by 30% or more between 2008 and 2018. This projection is based on the Bureau’s assumptions that demographic trends Therapy and advances in medical technology will continue to fuel demand for therapy services. Occupational therapy workforce shortages are appear- ing in selected markets and sectors. Demand for occu- pational therapy services in early intervention programs and in schools that enroll children with disabilities who are served under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 remains strong. Newly emerging areas of practice for occupational therapy practitioners related to the needs of an aging population are increasing demand for services. These in- clude low-vision rehabilitation; treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia, including caregiver training; older driver safety and rehabilitation; assisted living; and home safety and home modifications to en- able “aging in place.” In a survey of education program directors, the overwhelming majority (80%+) of the 318 programs reported that more than 80% of occupational therapy and occupational therapy assistant graduates were able to secure jobs within 6 months of graduation. Many of these graduates had secured job offers prior to graduating. Current Workforce Based on 2010 survey results from state occupational therapy regulatory boards, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) estimates the current active occupational therapy workforce to be roughly 137,000 practitioners.