SHAD Volume 18 ID Book.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

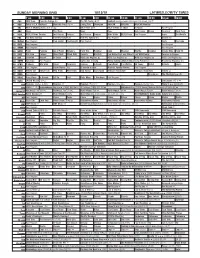

Sunday Morning Grid 10/13/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/13/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Saving Pets Champion NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Monster 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Hearts of Rock-Park 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jentzen Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb REAL-Diego Paid Program Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Seaver (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Cooking Simply Ming Food 50 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Mixed Nutz Mixed Nutz Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Feel Better Fast and Make It Last With Daniel Fascism in Europe 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como dice el dicho Por tu maldito amor (1990) Vicente Fernández. -

Star Channels, May 20-26

MAY 20 - 26, 2018 staradvertiser.com LEGAL EAGLES Sandra’s (Britt Robertson) confi dence is shaken when she defends a scientist accused of spying for the Chinese government in the season fi nale of For the People. Elsewhere, Adams (Jasmin Savoy Brown) receives a compelling offer. Chief Judge Nicholas Byrne (Vondie Curtis-Hall) presides over the Southern District of New York Federal Court in this legal drama, which wraps up a successful freshman season. Airing Tuesday, May 22, on ABC. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | FOR THE PEOPLE Case closed ABC’s ‘For the People’ wraps Deavere Smith (“The West Wing”) rounds example of how the show delves into both the out the cast as no-nonsense court clerk Tina professional and personal lives of the charac- rookie season Krissman. ters. It’s a formula familiar to fans of Shonda The cast of the ensemble drama is now part Rhimes, who’s an executive producer of “For By Kyla Brewer of the Shondaland dynasty, which includes hits the People,” along with Davies, Betsy Beers TV Media “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Scandal” and “How to Get (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Donald Todd (“This Is Us”) Away With Murder.” The distinction was not and Tom Verica (“How to Get Away With here’s something about courtroom lost on Rappaport, who spoke with Murder”). -

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE The Maltese Falcon introduced a new detective – Sam Spade – whose physical aspects (shades of his conversation with Stein) now approximated Hammett’s. The novel also originated a fresh narrative direction. The Op related his own stories and investigations, lodging his idiosyncrasies, omissions and intuitions at the core of Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. For The Maltese Falcon Hammett shifted to a neutral, but chilling third-person narration that consistently monitors Spade from the outside – often insouciantly as a ‘blond satan’ or a smiling ‘wolfish’ cur – but never ventures anywhere Spade does not go or witnesses anything Spade doesn’t see. This cold-eyed yet restricted angle prolongs the suspense; when Spade learns of Archer’s murder we hear only his end of the phone call – ‘Hello . Yes, speaking . Dead? . Yes . Fifteen minutes. Thanks.’ The name of the deceased stays concealed with the detective until he enters the crime scene and views his partner’s corpse. Never disclosing what Spade is feeling and thinking, Hammett positions indeterminacy as an implicit moral stance. By screening the reader from his gumshoe’s inner life, he pulls us into Spade’s ambiguous world. As Spade consoles Brigid O’Shaughnessy, ‘It’s not always easy to know what to do.’ The worldly cynicism (Brigid and Spade ‘maybe’ love each other, Spade says), the coruscating images of compulsive materialism (Spade no less than the iconic Falcon), the strings of point-blank maxims (Spade’s elegant ‘I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble’): Sam Spade was Dashiell Hammett’s most appealing and enduring creation, even before Bogart indelibly limned him for the 1941 film. -

XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY in the LAKE (1947, 105 Min)

September 22, 2015 (XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY IN THE LAKE (1947, 105 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Directed by Robert Montgomery Written by Steve Fisher (screenplay) based on the novel by Raymond Chandler Produced by George Haight Music by David Snell and Maurice Goldman (uncredited) Cinematography by Paul Vogel Film Editing by Gene Ruggiero Art Direction by E. Preston Ames and Cedric Gibbons Special Effects by A. Arnold Gillespie Robert Montgomery ... Phillip Marlowe Audrey Totter ... Adrienne Fromsett Lloyd Nolan ... Lt. DeGarmot Tom Tully ... Capt. Kane Leon Ames ... Derace Kingsby Jayne Meadows ... Mildred Havelend Pink Horse, 1947 Lady in the Lake, 1945 They Were Expendable, Dick Simmons ... Chris Lavery 1941 Here Comes Mr. Jordan, 1939 Fast and Loose, 1938 Three Morris Ankrum ... Eugene Grayson Loves Has Nancy, 1937 Ever Since Eve, 1937 Night Must Fall, Lila Leeds ... Receptionist 1936 Petticoat Fever, 1935 Biography of a Bachelor Girl, 1934 William Roberts ... Artist Riptide, 1933 Night Flight, 1932 Faithless, 1931 The Man in Kathleen Lockhart ... Mrs. Grayson Possession, 1931 Shipmates, 1930 War Nurse, 1930 Our Blushing Ellay Mort ... Chrystal Kingsby Brides, 1930 The Big House, 1929 Their Own Desire, 1929 Three Eddie Acuff ... Ed, the Coroner (uncredited) Live Ghosts, 1929 The Single Standard. Robert Montgomery (director, actor) (b. May 21, 1904 in Steve Fisher (writer, screenplay) (b. August 29, 1912 in Marine Fishkill Landing, New York—d. September 27, 1981, age 77, in City, Michigan—d. March 27, age 67, in Canoga Park, California) Washington Heights, New York) was nominated for two Academy wrote for 98 various stories for film and television including Awards, once in 1942 for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Here Fantasy Island (TV Series, 11 episodes from 1978 - 1981), 1978 Comes Mr. -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

Honey, You Know I Can't Hear You When You Aren

Networking Knowledge Honey, You Know I Can’t Hear You (Jun. 2017) Honey, You Know I Can’t Hear You When You Aren’t in the Room: Key Female Filmmakers Prove the Importance of Having a Female in the Writing Room DR ROSANNE WELCH, Stephens College MFA in Screenwriting; California State University, Fullerton ABSTRACT The need for more diversity in Hollywood films and television is currently being debated by scholars and content makers alike, but where is the proof that more diverse writers will create more diverse material? Since all forms of art are subjective, there is no perfect way to prove the importance of having female writers in the room except through samples of qualitative case studies of various female writers across the history of film. By studying the writing of several female screenwriters – personal correspondence, interviews and their writing for the screen – this paper will begin to prove that having a female voice in the room has made a difference in several prominent films. It will further hypothesise that greater representation can only create greater opportunity for more female stories and voices to be heard. Research for my PhD dissertation ‘Married: With Screenplay’ involved the work of several prominent female screenwriters across the first century of filmmaking, including Anita Loos, Dorothy Parker, Frances Goodrich and Joan Didion. In all of their memoirs and other writings about working on screenplays, each mentioned the importance of (often) being the lone woman in the room during pitches and during the development of a screenplay. Goodrich summarised all their experiences concisely when she wrote, ‘I’m always the only woman working on the picture and I hold the fate of the women [characters] in my hand… I’ll fight for what the gal will or will not do, and I can be completely unfeminine about it.’ Also, the rise of female directors, such as Barbra Streisand or female production executives, such as Kathleen Kennedy, prove that one of the greatest assets to having a female voice in the room is the ability to invite other women inside. -

The Summer Chronicle

The Summer Chronicle llth Year, Number 6 Duke University, Durham, North Carolina Wednesday, June 17, 1981 Trustees OK hospital budget, rate hikes By Erica Johnston increase by 12 percent to 15 calls for an expense budget of Patients at Duke Hospital percent. $169.7 million, an increase of 8.5 will pay an average of 11 The hikes were part of the percent over last year's, and a percent more for their rooms Hospital's fiscal 1982 budget revenue budget of $175.4 starting July 1 due to an proposal presented to the million. increased revenue budget for executive committee by Andrew In response to a trustee's the Hospital approved by the Wallace, chief executive officer question, Wallace said Duke executive committee of the of the Hospital. Hospital "will still be the most Board of Trustees last Friday. The increase — the second for expensive in the Piedmont On July 1, rates will inrease room rates in six months — is region," but added that the rate from $216 to $231 or by nine needed to make the Hospital's by which Duke's room fees have percent for semi-private rooms, projected revenue budget exceed increased is lower than about from $220 to $240 for private the expense budget to balance half ofthe hospitals' in the area. rooms and from $580 to $705 inflationary factors and help Duke Hospital's rates are daily, or by 22 percent, for decrease the Hospital's $3.5 higher than other area rooms in the intensive care unit. million deficit, Wallace hospitals largely because Duke Charges for out-patient visits explained after the meeting. -

Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, a Case Study

Katie Walsh Selling Masculinity at Warner Bros.: William Powell, A Case Study Abstract William Powell became a star in the 1930s due to his unique brand of suave charm and witty humor—a quality that could only be expressed with the advent of sound film, and one that took him from mid-level player typecast as a villain, to one of the most popular romantic comedy leads of the era. His charm lay in the nonchalant sophistication that came naturally to Powell and that he displayed with ease both on screen and off. He was exemplary of the success of the new kind of star that came into their own during the transition to sound: sharp- or silver-tongued actors who were charming because of their way with words and not because of their silver screen faces. Powell also exercised a great deal of control over his publicity and star image, which is best examined during his short and failed tenure as a Warner Bros. during the advent of his rise to stardom. Despite holding a great amount of power in his billing and creative control, Powell was given a parade of cookie-cutter dangerous playboy roles, and the terms of his contract and salary were constantly in flux over the three years he spent there. With the help of his agent Myron Selznick, Powell was able to navigate between three studios in only a matter of a few years, in search of the perfect fit for his natural abilities as an actor. This experimentation with star image and publicity marked the period of the early 1930s in Hollywood, as studios dealt with the quickly evolving art and technological form, industrial and business practices, and a shifting cultural and moral landscape. -

Thoughts on the Thin Man Essays on the Delightful Detective Work of Nick and Nora Charles

THOUGHTS ON THE THIN MAN ESSAYS ON THE DELIGHTFUL DETECTIVE WORK OF NICK AND NORA CHARLES PDF-22TOTTMEOTDDWONANC13 | Page: 92 File Size 4,045 KB | 29 May, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Brief Description Main Topic Technical Note Appendix Glossary PDF File: Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles - 1/2 PDF-22TOTTMEOTDDWONANC13 Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles e-Book Name : Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles - Read Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles PDF on your Android, iPhone, iPad or PC directly, the following PDF file is submitted in 29 May, 2020, Ebook ID PDF-22TOTTMEOTDDWONANC13. Download full version PDF for Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles using the link below: Download: THOUGHTS ON THE THIN MAN ESSAYS ON THE DELIGHTFUL DETECTIVE WORK OF NICK AND NORA CHARLES PDF The writers of Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles have made all reasonable attempts to offer latest and precise information and facts for the readers of this publication. The creators will not be held accountable for any unintentional flaws or omissions that may be found. PDF File: Thoughts On The Thin Man Essays On The Delightful Detective Work Of Nick And Nora Charles - 2/2 PDF-22TOTTMEOTDDWONANC13. -

More-1930S-Films

SKH Note: Below section edited out of original MOST EVIL(I) due to space limitations. 1930s films as M.O. We have examined two 1930s-period films, The Most Dangerous Game (1932) and Charlie Chan at Treasure Island (1939) and I have suggested that Zodiac, in his 1960s murders, was borrowing themes and characters from each film. Let us now examine two additional films from that period, which I believe buttress my theory. In February, 1934, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studio distributed a U.K. made film, The Mystery of Mr. X. The film starred a young Robert Montgomery, as Sir Nicholas Revel. The story involved a mad serial killer, “Mr. X”, who uses a rapier- like sword to stab and slay unsuspecting uniformed policemen, walking their beats in different sections of London. Mr. X, after slaying his victims, then mails taunting cut-and-pasted notes to the press, and as the film rushes to its climax, our hero, Sir Nicholas, by plotting the locations of the murder victims on a city map, cleverly deduces that the killer is constructing a giant letter X, with only one killing more needed to complete his “project.” Sir Nicholas, disguised in the uniform of a Bobbie, decides to use himself as bait, and drives to the anticipated final location, where he confronts Mr. X for a fight-to-the-finish finale.1 a b 1 In 1952, the film was remade for the big screen as, The Hour of 13, this time starring Peter Lawford as, Sir Nicholas. In the remake, the serial killer, renamed “The Terror” chose his victims locations throughout 1890 London town, to form the letter “T”. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 27 Dresses DVD-8204 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 28 Days Later DVD-4333 10th Victim DVD-5591 DVD-6187 12 DVD-1200 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 12 and Holding DVD-5110 3 Women DVD-4850 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 12 Monkeys DVD-3375 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 1776 DVD-0397 300 DVD-6064 1900 DVD-4443 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 1984 (Hurt) DVD-4640 39 Steps DVD-0337 DVD-6795 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 1984 (Obrien) DVD-6971 400 Blows DVD-0336 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 42 DVD-5254 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 50 First Dates DVD-4486 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 500 Years Later DVD-5438 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-0260 61 DVD-4523 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 70's DVD-0418 2012 DVD-4759 7th Voyage of Sinbad DVD-4166 2012 (Blu-Ray) DVD-7622 8 1/2 DVD-3832 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 8 Mile DVD-1639 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 9 to 5 DVD-2063 25th Hour DVD-2291 9.99 DVD-5662 9/1/2015 9th Company DVD-1383 Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet DVD-0831 A.I.