Honey, You Know I Can't Hear You When You Aren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dramatization of the Diary of Anne Frank and Its Influence on American Cultural Perceptions

GOOD AT HEART: THE DRAMATIZATION OF THE DIARY OF ANNE FRANK AND ITS INFLUENCE ON AMERICAN CULTURAL PERCEPTIONS A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Whitney Lewis Stalnaker May, 2016 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Whitney Lewis Stalnaker B.S., Glenville State College, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by Dr. Richard Steigmann-Gall , Advisor Dr. Kenneth Bindas , Chair, Department of History Dr. James Blank , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... iii PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 Historiography ...............................................................................................................5 Methodology ..................................................................................................................9 Why This Play? ............................................................................................................12 CHAPTERS -

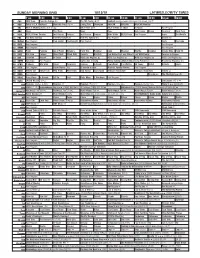

Sunday Morning Grid 10/13/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/13/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Saving Pets Champion NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Monster 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Hearts of Rock-Park 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jentzen Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb REAL-Diego Paid Program Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Seaver (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Cooking Simply Ming Food 50 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Mixed Nutz Mixed Nutz Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Feel Better Fast and Make It Last With Daniel Fascism in Europe 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como dice el dicho Por tu maldito amor (1990) Vicente Fernández. -

Star Channels, May 20-26

MAY 20 - 26, 2018 staradvertiser.com LEGAL EAGLES Sandra’s (Britt Robertson) confi dence is shaken when she defends a scientist accused of spying for the Chinese government in the season fi nale of For the People. Elsewhere, Adams (Jasmin Savoy Brown) receives a compelling offer. Chief Judge Nicholas Byrne (Vondie Curtis-Hall) presides over the Southern District of New York Federal Court in this legal drama, which wraps up a successful freshman season. Airing Tuesday, May 22, on ABC. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | FOR THE PEOPLE Case closed ABC’s ‘For the People’ wraps Deavere Smith (“The West Wing”) rounds example of how the show delves into both the out the cast as no-nonsense court clerk Tina professional and personal lives of the charac- rookie season Krissman. ters. It’s a formula familiar to fans of Shonda The cast of the ensemble drama is now part Rhimes, who’s an executive producer of “For By Kyla Brewer of the Shondaland dynasty, which includes hits the People,” along with Davies, Betsy Beers TV Media “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Scandal” and “How to Get (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Donald Todd (“This Is Us”) Away With Murder.” The distinction was not and Tom Verica (“How to Get Away With here’s something about courtroom lost on Rappaport, who spoke with Murder”). -

The Glorious Career of Comedienne Judy Holliday Is Celebrated in a Complete Nine-Film Retrospective

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1996 Contact: Graham Leggat 212/708-9752 THE GLORIOUS CAREER OF COMEDIENNE JUDY HOLLIDAY IS CELEBRATED IN A COMPLETE NINE-FILM RETROSPECTIVE Series Premieres New Prints of Born Yesterday and The Marrying Kind Restored by The Department of Film and Video and Sony Pictures Born Yesterday: The Films of Judy Holliday December 27,1996-January 4,1997 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Special Premiere Screening of the Restored Print of Born Yesterday Introduced in Person by Betty Comden on Monday, December 9,1996, at 6:00 p.m. Judy Holliday approached screen acting with extraordinary intelligence and intuition, debuting in the World War II film Winged Victory (1944) and giving outstanding comic performances in eight more films from 1949 to 1960, when her career was cut short by illness. Beginning December 27, 1996, The Museum of Modern Art presents Born Yesterday: The Films of Judy Holliday, a complete retrospective of Holliday's short but exhilarating career. Holliday's experience working with director George Cukor on Winged Victory led to a collaboration with Cukor, Garson Kanin, and Kanin's wife Ruth Gordon, resulting in Adam's Rib (1949), Born Yesterday (1950), The Marrying Kind (1952), and // Should Happen To You (1952). She went on to make Phffft (1954), The Solid Gold Cadillac (1956), Full of Life (1956), and, for director Vincente Minnelli, Bells Are Ringing (1960). -more- 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019 Tel: 212-708-9400 Fax: 212-708-9889 2 The Department of Film and Video and Sony Pictures Entertainment are restoring the six films that Holliday made at Columbia Pictures from 1950 to 1956. -

Kansas City Repertory Theatre Announces Acclaimed Cast for the Diary of Anne Frank Jan

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ellen McDonald 816.444.0052 or 816.213.4355 [email protected] FOR TICKETS: Box Office at 816.235.2700 or www.KCRep.org. Kansas City Repertory Theatre Announces Acclaimed Cast for The Diary of Anne Frank Jan. 29 through Feb. 21, 2016 at newly renovated Spencer Theatre Kansas City, MO (Jan. 5, 2016) – Kansas City Repertory Theatre’s Artistic Director Eric Rosen is pleased to announce the cast of The Diary of Anne Frank, directed by Marissa Wolf, KC Rep’s Director of New Works. The play, based upon Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, was originally written for the stage by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett. In 1997, Wendy Kesselman published a revised version of Goodrich and Hackett’s Pulitzer Prize winning script, which integrated some of the more personal aspects of Anne Frank’s story that remained untold in the original script. Peer into the world of a family in hiding and a gifted young writer who came of age during the horrors of the Holocaust. Through Anne’s eyes, we see the prevailing hopes of a girl who – despite everything – inspired generations with her unwavering faith in humanity. This production begins Friday, Jan. 29 and runs through Sunday, Feb. 21 at KC Rep’s newly renovated Spencer Theatre. Kansas City Repertory Theatre Announces Cast for The Diary of Anne Frank Jan. 29 through Feb. 21 at Spencer Theatre Page 1 “This work by Wendy Kessleman is stunningly lyrical and poetic,” stated Wolf. “My hope is that KC Rep audiences will connect intimately with Anne as a budding young woman and all that goes with a young and emerging heart, in spite of the world looming outside.” The ensemble cast, drawn locally as well as from across the country, includes: Daniel Beeman as Peter Van Daan, Martin Buchanan as Mr. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

The Prince of Tides a Novel by Pat Conroy

The Prince of Tides A Novel by Pat Conroy You're readind a preview The Prince of Tides A Novel ebook. To get able to download The Prince of Tides A Novel you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited ebooks*. Accessible on all your screens. *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every book is in the library. But if You are still not sure with the service, you can choose FREE Trial service. Book File Details: Review: There is graphic violence and sexual content. However, none of it is gratuitous. It is well- used in telling the story. This is my FAVORITE novel. It is a challenging read, in that it is extremely evocative of deep emotion. Pat Conroys writing is so lovely. I visited the southern part of NC Coast and northern part of SC coast almost every summer as... Original title: The Prince of Tides: A Novel 704 pages Publisher: Dial Press Trade Paperback; Reprint edition (October 2002) Language: English ISBN-10: 0553381547 ISBN-13: 978-0553381542 Product Dimensions:5.2 x 1.6 x 8.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 3507 kB Book File Tags: pat conroy pdf, prince of tides pdf, south carolina pdf, years ago pdf, tom wingo pdf, new york pdf, read this book pdf, well written pdf, beach music pdf, beautifully written pdf, low country pdf, ever read pdf, wingo family pdf, english language pdf, lords of discipline pdf, seen the movie pdf, dysfunctional family pdf, highly recommend pdf, nick nolte pdf, great santini Description: “A big, sprawling saga of a novel” (San Francisco Chronicle), this epic family drama is a masterwork by the revered author of The Great Santini.Pat Conroy’s classic novel stings with honesty and resounds with drama. -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

«Itos a I Page 6 Oictif 1*Mb Television `Simpsons' Again Denied Shot at Comedy Category

Daily News L.A.LIFEThursday. February 20. 1992 Ccpyrlghl .0 1992 New tune Any way you slice it, Popeil will sing about it Page 5 Fashion Women right in style with that menswear look «itos a I Page 6 OiCtif 1*Mb Television `Simpsons' again denied shot at comedy category Page 24 Hollywood Gerald() delves sh Belle in "Beauty and the Beast" into Natalie Wood's death Highlights box: Page 25 —Streisand snubbed — 'Secret," Singleton make history Music —Caregory-by-category analysis — Let of nominees John Mellencamp — Full coverage begins on page 29 performs blah set to adoring fans Page 26 Annette Bening and Warren Beatty In "Bugsy," which led all films with 10 Oscar nominations. '12. • •• •• DAILY NEWS THLFWAY TEESUARY 20, 1992 LA. 1.11111-3 PAGE 3 .01""'N .si' ,NortN."4'6%. err ".avroe144 Page 3 Talk Line Were mar Me Academy of Motion Who could can forget the Picture Aru and Sciences folks are heartwarming story of a conniving dims Jeeping in this morning after drifter and his ever so cute "I could Wednesdays !JO a.01. command have played Annie on Broadway, if I terfirmance. had a better agent father" in "Curly But Page 3 Talk Line callers can't be Sue." The only downside of the picture was that Brian Dennehy wasn't in it. 'aught 'Winne. — }Lamy Fleckman Yen acre risk an top of the academy, North Hollywood astigating voters for slighting Barbra ;treatise!. heaping praise on "Beauty "I FK" represents the foss of and the Beam ' 'VFW" and 'The Prince S1101106 innocence and the last of the great if Tides." the films. -

April 9 Email Schedule

SUNDAY – APRIL 9 7:00 PT / 8:00 MT: CALL THE MIDWIFE. The Nonnatus team prepares for the birth of a baby they know may not survive. Shelagh shows her mettle when she is first on the scene after an explosion in the docks. Sister Ursula continues to ruffle feathers with her unpopular decisions. (60 Min) 8:00 PT / 9:00 MT: HOME FIRES SEASON TWO ON MASTERPIECE. The attraction between Pat and Marek continues to grow, but the risk of acting on their feelings is huge. At the reading of his will, Frances discovers that Peter was keeping a secret from her. (60 Min) 9:00 PT / 10:00 MT: WOLF HALL ON MASTERPIECE “Episode Two.” Cardinal Wolsey has been forced to move to York. Cromwell remains in London, seeking to return the cardinal to the king's favor. As Cromwell's relationship with Henry deepens, there is unexpected news from the north. (90 Min) 10:30 PT / 11:30 MT: VICIOUS. Freddie and Stuart shop for a new coat for Freddie for his fan club event. Since the coat is more expensive than they'd expected, Stuart finds a way of secretly raising some cash. (30 Min) MONDAY – APRIL 10 7:00 PT / 8:00 MT: WASHINGTON GROWN “Chicken.” Food is what Washington Grown is all about! From the field to the plate and everything in between Washington Grown highlights the amazing food scene and industry that makes Washington state a great place enjoy literally hundreds of locally grown items. Washington Grown tells the story about what Washington's 300 some crops provide to our meals, our culture, our economy, and the world. -

{DOWNLOAD} the More the Merrier Ebook

THE MORE THE MERRIER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne Fine | 160 pages | 28 Nov 2006 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780440867333 | English | London, United Kingdom The More the Merrier PDF Book User Ratings. It doesn't sound that hard to think up but the events that lead toward the end result where the parts that are hard to think up when writing. Washington officials objected to the title and plot elements that suggested "frivolity on the part of Washington workers". Release Dates. Edit page. Emily in Paris. Joe asks Connie to go to dinner with him. User Reviews. Dingle calls Joe to meet him for dinner. Apr 28, Or that intimate scene where McCrea gives a carrying case to Jean Arthur. External Sites. Their acting is so subtly romantic in that scene. Two's a Crowd screenplay by Garson Kanin uncredited [1]. Save Word. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. The Good Lord Bird. It's shocking how believably he pulls off the scene in which McCrea and Arthur wander around the apartment without bumping into each other. Quotes [ first lines ] Narrator : Our vagabond camera takes us to beautiful Washington, D. Alternate Versions. If you like classic comedies then this must be on your watch list. Share the more the merrier Post the Definition of the more the merrier to Facebook Share the Definition of the more the merrier on Twitter. The More the Merrier Writer New York: Limelight Editions. September 16, Rating: 4. Tools to create your own word lists and quizzes. Variety Staff. You may later unsubscribe. -

Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, Writers Of

letting a crew film their life for the better Wonderful Life (1946)—which they didn’t part of a year, hadn’t experienced the inter- like—as well as the stage adaptation of The vening period in which, thanks to Jenny Diary of Anne Frank (1955), for which they Jones and Jerry Springer and Fear Factor, it won their Pulitzer and are probably best has become grotesquely obvious that many remembered today. Americans will do anything to be on televi- In this engaging and spirited biography— sion. And what seemed such sensational TV the title alludes to The Thin Man, of course: the in 1973—the dissolution of an apparently duo were so charming and amusing that ideal marriage, the efflorescence of a gay William Powell and Myrna Loy needed only to teenager—seems commonplace now. What imitate them—David Goodrich, a nephew, remain goofily interesting are some of the reveals that the scriptwriters were much more details: how, for example, some years after the than “good hacks,” and a very lucky thing for the broadcast, the Los Angeles public television rest of us, too, not to mention the stars they station offered, as a pledge-drive premium, a wrote for. They were eclectic craftsmen with the weekend with the splintered Loud family. swank of Bel Air and the work ethic of dray I look forward to talk-show appearances horses. “We shouldn’t take so much trouble,” in which I can explain what I really mean in Frances admitted, “but it is only to satisfy our- this review, and subsequently, one can only selves.” A friend likened their work to “fine cab- hope, a documentary on the making of one inet-making.” They were “professionals whose of those shows.