Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <Em>Othello</Em>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iago and His Motives Under Modern Eyes Amany Abdelrazik

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS) Vol-3, Issue-4, Jul - Aug, 2018 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.3.4.28 ISSN: 2456-7620 Iago and His Motives under Modern Eyes Amany Abdelrazik PHD Researcher - Freie Universität Berlin, Germany Abstract—Shakespeare's plays depict the turn from the to the issues which appear in Othello have greatly pre-modern era with its traditional values and mores into changed between Shakespeare’s time and our the modern approach towards life and individuals. These own...” (Holloway, 1961, p. 155), I am encouraged plays deal with specific questions that were significant in to re-read Iago´s behaviour in light of modern Shakespeare's time and his cultural contexts, such as the thought that could satisfy the modern individual mores and meanings of Christian values in the society, understanding without taking the text out of its the rise of humanism, monarchy and questions related to original context. the economy. Nonetheless, Shakespeare´s questions on Rereading Iago´s behaviour through the religious values and the modern individual seem to be modern lens, I am going to contradict relevant today, in particular, with the recent post-modern Coleridge´s claim of Iago´s “motiveless discussions on the limits of secular rational modernity malignity” through trying out two and a return to a new condition of believing in arguments. Firstly, I argue that Iago´s contemporary societies. Taking the character of Iago as motives lurked inside his own narcissist my reference point, I shall attempt to reread Iago´s character that believed deeply in the actions and psyche in light of a critique of the narcissist individual’s willpower. -

The Elusive Ensign: Towards a “ Grammar” of Iago's Motives

The elusive ensign: towards a “grammar” of Iago’s motives Keith Gregor UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA Of all Iago’s gestures few are more unsettling than his defiant final words to his captors: “De- mand me nothing; what you know, you know: /From this time forth I never will speak word” (5. 2. 300-1)1. And so his part in Othello concludes, the real reasons for his “fault” being left for his torturers’ ears —and to the audience’s imagination. No one would “demand” him anything, were it not for that endless dialogue between work and interpreter which has been the hallmark of post- early modern critical practice. Just as art is seen to begin at the edges of the author’s “existential reality”, so the disappearance of the player is regarded as the condition of his re-birth as a character. In the case of Iago, this re-birth tends to hinge on the recovery of that most elusive element: the ensign’s motives. The concept of character would then seem inseparable from an account of motivation. After all, both concepts emerge at the same historical moment. Elizabethans, it seems, explained action in terms of a taxonomy of humours or the equally venerable dichotomy of virtue and vice (Scragg 1968). The “motiveless malignity” which Coleridge found lurking in Iago would mean little to an audience which, as Bradbrook noted, “did not expect every character to produce one rational explanation for every given action” (1983, 59-60). Iago’s silence would thus be an adequate response for an audience which failed, or simply refused, to see beyond the deed. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

William Shakespeare's the TAMING of the SHREW a STUDY GUIDE

The Classic Theatre of San Antonio Presents William Shakespeare’s THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Directed by Diane Malone A STUDY GUIDE Prepared by The Classic Theatre of San Antonio November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward by Diane Malone, Director/Designer .............................................................................1 The Dramaturgical Research Process by Timothy Retzloff, Dramaturg ...................................................................................2 About William Shakespeare, Playwright (1564-1616) .......................................................4 Principal Characters .............................................................................................................5 Synopsis of the Play ...............................................................................................................6 Map of Renaissance Italy .....................................................................................................8 Cast, Production Staff, and Theatre Staff ..........................................................................9 Interviews with Some of the Cast ......................................................................................10 Reflections on the Play and Performance .........................................................................15 Rehearsal Photographs .......................................................................................................16 Works Cited ........................................................................................................................18 -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

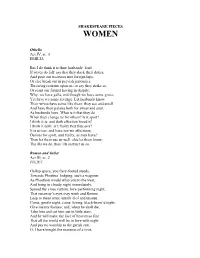

SHAKESPEARE PIECES Othello Act IV, Sc. 3 EMILIA but I Do Think It Is

SHAKESPEARE PIECES WOMEN Othello Act IV, sc. 3 EMILIA But I do think it is their husbands’ fault If wives do fall: say that they slack their duties, And pour our treasures into foreign laps, Or else break out in peevish jealousies, Throwing restraint upon us; or say they strike us, Or scant our former having in despite; Why, we have galls, and though we have some grace, Yet have we some revenge. Let husbands know Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell And have their palates both for sweet and sour, As husbands have. What is it that they do When they change us for others? Is it sport? I think it is: and doth affection breed it? I think it doth: is’t frailty that thus errs? It is so too: and have not we affections, Desires for sport, and frailty, as men have? Then let them use us well: else let them know, The ills we do, their ills instruct us so. Romeo and Juliet Act III, sc. 2 JULIET Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds, Towards Phoebus’ lodging: such a wagoner As Phaethon would whip you to the west, And bring in cloudy night immediately. Spread thy close curtain, love-performing night, That runaway’s eyes may wink and Romeo Leap to these arms, untalk’d of and unseen. Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night, Give me my Romeo; and, when he shall die, Take him and cut him out in little stars, And he will make the face of heaven so fine That all the world will be in love with night And pay no worship to the garish sun. -

Othello As an Enigma to Himself: a Jungian Approach to Character Analysis Eric Iliff Eastern Washington University

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2013 Othello as an enigma to himself: a Jungian approach to character analysis Eric Iliff Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Iliff, Eric, "Othello as an enigma to himself: a Jungian approach to character analysis" (2013). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 138. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/138 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Othello as an Enigma to Himself: A Jungian Approach to Character Analysis A Thesis Presented to Eastern Washington University Cheney, Wa In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts (Literary Studies) By Eric Iliff Spring 2013 I l i f f ii THESIS OF ERIC ILIFF APPROVED BY Dr. Grant Smith, Chair, Graduate Study Committee Date Dr. Philip Weller, Graduate Study Committee Date Dr. Martha Raske, Graduate Study Committee Date I l i f f iii Table of Contents Introductio n .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Procedure ..................................................................................................................................................... -

A Level Literature Paper One – Othello - Knowledge Organiser Assessment: Essay on a Critical View of Love in Othello Supported by an Extract

A Level Literature Paper One – Othello - Knowledge Organiser Assessment: Essay on a critical view of love in Othello supported by an extract. Possible topics: Attitudes to love of the key characters (Othello, Desdemona, Emilia, Iago, Brabantio, Roderigo, Cassio,), father/daughter love, love and marriage, female attitudes to love, male attitudes to love, love and race, sex and desire, love and control, jealousy, love and honour, love and class. “I am not what I am” – Iago (1.1) “An old black ram is tupping your white ewe” – Iago (1.1) “she shunned the wealthy curled darlings of our “for your sake, jewel, I am glad at soul I have no nation… run from her guardage to the sooty bosom other child” “she has deceived her father and may of such a thing as thou” – Brabantio (1.2) thee” Brabantio (1.3) “moth of peace” – Desdemona (1.3) “she gave me for my pains a world of sighs”, “she loved me for the dangers I had passed” – Othello about him and Desdemona’s love (1.3) “twixt my sheets, he’s done my office” – Iago’s “I will incontinently drown myself” Roderigo as suspicions (1.3) Petrarchan lover (1.3) “My fair warrior” – Othello (2.1) “to suckle fools and chronicle small beer” – Iago (2.1) “the divine Desdemona” – Cassio (2.1) “The riches of the ship is come onshore” – Cassio (2.1) “I do suspect the lusty Moor, hath leap’d into my “most fresh and delicate creature” – Cassio seat” – Iago 2.1 Versus “full of game” – Iago (2.3) “Are we turned Turk?” – Othello 2.3 “His soul is so enfettered to her love” – Iago (2.3) “Out of her own goodness make the -

(Un)Doing Desdemona: Gender, Fetish, and Erotic Materialty in Othello

(UN)DOING DESDEMONA: GENDER, FETISH, AND EROTIC MATERIALTY IN OTHELLO A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Literature By Perry D. Guevara, B.A. Washington, DC May 1, 2009 Dedicated to Cecilia (and Francisco, in memoriam) ii Acknowledgements (Un)Doing Desdemona: Gender, Fetish, and Erotic Materiality in Othello began as a suspicion—a mere twinkle of an idea—while reading Othello for Mimi Yiu's graduate seminar Shakespeare's Exotic Romances. I am indebted to Dr. Yiu for serving as my thesis advisor and for seeing this project through to its conclusion. I am also thankful to Ricardo Ortiz for serving on my oral exam committee and for ensuring that my ideas are carefully thought through. Thanks also to Lena Orlin, Dana Luciano, Patrick O'Malley, and M. Lindsay Kaplan for their continued instruction and encouragement. The feedback I received from Jonathan Goldberg (Emory University) and Mario DiGangi (City University University of New York—Graduate Center) proved particularly helpful during the final phases of writing. Furthermore, my thesis owes its life to my peers, not only for their generous feedback, but also for their invaluable friendship, especially Roya Biggie, Olga Tsyganova, Renata Marchione, Michael Ferrier, and Anna Kruse. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Donna and Jess Guevara, for their unconditional love and support even though they think my work is “over their heads.” iii Table of Contents Introduction .........................................................................................................................1 Desdemona's Dildo............................................................................................................18 Coda ..................................................................................................................................68 iv I. -

Othello and the "Plain Face" of Racism Author(S): Martin Orkin Source: Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol

George Washington University Othello and the "plain face" Of Racism Author(s): Martin Orkin Source: Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Summer, 1987), pp. 166-188 Published by: Folger Shakespeare Library in association with George Washington University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2870559 . Accessed: 16/07/2011 13:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=folger. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Folger Shakespeare Library and George Washington University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Shakespeare Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org Othello and the "plain face" Of Racism MARTIN ORKIN OLOMON T. -

Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch An Intimate and Intermedial Form: Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J. This is a preliminary version of a book chapter published in Shakespeare Survey 69: Shakespeare and Rome, Cambridge University Press, pp. 347-360, ISBN 9781107159068 Details of the book are available on the publisher’s website: https://www.cambridge.org/core/what-we-publish/collections/shakespea... The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 An intimate and intermedial form: early television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 In the twenty-seven months between February 1937 and April 1939 the fledgling BBC television service from Alexandra Palace broadcast more than twenty Shakespeare adaptations.1 The majority of these productions were short programmes featuring ‘scenes from…’ the plays, although there were also substantial adaptations of Othello (1937), Julius Caesar (1938), Twelfth Night and The Tempest (both 1939) as well as a presentation of David Garrick’s 1754 version of The Taming of the Shrew, Katharine and Petruchio (1939). There were other Shakespeare-related programmes as well, and the playwright himself appeared in three distinct historical dramas. In large part because no recordings exist of these transmissions (or of any British television Shakespeare before 1955), these ‘lost’ adaptations have received little scholarly attention. -

Shakespeare's Othello Beyond the Boundaries of the Page

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-7917.2015v20n2p11 SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO BEYOND THE BOUNDARIES OF THE PAGE: AN ANALYSIS OF TWO FILMIC PRODUCTIONS Camila Paula Camilotti* Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Abstract: This article aims at observing and analyzing two filmic productions ofWilliam Shakespeare’s Othello. The first, entitled Othello, was directed, produced and starred by Orson Welles in 1952 andthe second, also entitled Othello, was directed by Oliver Parker in 1995. My main interest in studying these two filmic productions is to observe – based on the notions of theatrical adaptation by Jay Halio (2000), Patrice Pavis (1992), and Allan Dessen (2002) – how each director constructed the seduction moment that happens in Scene III, Act III of Shakespeare’s playtext in their filmic productions. The analysis proves that two different conceptions, separated in time and space, are capable of making Shakespeare’s timelessness transcend and make the modern spectators aware of the fact that the human artistic capacity is able to cross unimaginable limits of creativity and transform a great literary work of art in a great (filmic or theatrical) spectacle. Keywords: Shakespeare’s Othello. Welles’ Othello. Parker’s Othello. Conception. I have’t. It is engendered. Hell and night Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light. (II.I 403-404) Whenever a text (in this case, a Shakespearian playtext) crosses the boundaries of the page to live in a theatrical or cinematic medium, with all its visual (and sonorous) elements,it has inevitably to go through several alterations in order to be seen and heard by an audience, in a certain time and space.