Music As an Educative Enrichment Medium for the Remediation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y&T 23 July 2020 Edition-2.Indb

Creating a historical sport narrative of Zonnebloem College for classroom practice, pp . 71-104 Creating a historical sport narrative of Zonnebloem College for classroom practice DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2020/n23a4 Francois Cleophas University of Stellenbosch Stellenbosch, South Africa [email protected] ORCID No.: orcid.org/0000-0002-1492-3792 Abstract This article attempts to create a sport narrative of the Zonnebloem College prior to 1950. The introduction provides a motivation for proceeding with a decolonising format and lays out what the elements of such a format would entail. Next, an overview of sport historical developments at the Zonnebloem College is explored. The administrative history of sport at Zonnebloem is explored as well as selected sport codes. Finally, the article is summarised and concluded by presenting teachers and learners with sample questions, which they could consider using in their local conditions. Keywords: Athletics; Netball; Soccer; Decolonisation; Institutional Culture; Past Student's Union; Zonnebloem. Introduction According to the sport historian, André Odendaal, at the centre of South African sport history must be the effort to understand how the silences of the colonial subject in sport are manipulated and how colonial narratives are set in the literature and minds of South Africans – and to attempt to redress the situation (Odendaal 2018:1). One example of the silence on black school sport is the publication, Some famous schools. It is a 279- page work that is dedicated to “teachers, pupils, old boys, parents and the local public that [came from] schools founded on the Arnoldian ideal” (Peacock 1972: Editor’s Note). -

Hout Full Acknowledgementtown of the Source

H 0 U T B A Y A DEVELOPMENTAL Town STRATEGY Cape of R.A. BISSET University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree, Master of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Cape Town. October 1976. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University A C K N 0 W L E D G E M E N T S Dave Dewar - my supervisor, for his stimulating direction and encouragement, in the formulation of this strategic approach •••••.• The Divisional Council for affording access to statistical data ••••••• The Hout Bay Ratepayers' Association and the People of the Valley for the interest and time taken in discussions regarding the area .•...•• Audrey Foat for meticulous typing ••.•••. To all others who have assisted in the preparation of this Thesis •.•..•• i. C 0 N T E N T S CHAPTER PAGE 1. o. 0. Purpose of Thesis 1 1.1. o. Introduction 4 1.1.1. Spatial Delimi ta ti on 5 1.1.2. Attributes 6 2.0.0. Hout Bay's Role 11 2 .1. o. Local Role 12 2. 2. o. Metropolitan Role 14 2.3.0. Regional Role 18 2.4.0. National Role 19 2. 5. o. -

Groundswell of Good in the Cape of Good Hope Salvation Doesn’T Come to Us from the Top

Photo courtesy of Trevor Ball. See Pg 27. Groundswell of Good in the Cape of Good Hope Salvation doesn’t come to us from the top. It isn’t A bold statement, but think about it? In every positive handed down to us by our leaders and government, interaction we build community. In each caring though many of us spend our lives waiting for just that... moment, someone who felt alone and hopeless learns for life to improve because of policy changes made by that there is a community out there who cares about ‘major’ players. what happens to it’s members, a community who wants Over the past few months, I watched with a growing the best for everyone. fascination and sense of wonder as the Hout Bay For too long now, we have lived divided, isolated and Facebook community, individual by individual, began afraid. And in fear, we remain cold and disconnected, helping each other. I’ve seen attitudes change and strangers in a town of thousands. By being disconnected, understanding born, I’ve seen that the ‘major’ players by not knowing the people we all share space with, we are the people in your life who have a direct impact, the feed fear. ones on the ground, who make a difference. Be it Positively Hout Bay, Hout Bay Organised, Hout Just smile and say “Hi!” Bay Massive or any other group, people out there are communicating with, and learning about, each other. Yet this gentle bubble, this slow growing, luscious Dialogue goes back and forth, politics raises it’s head groundswell of communication and goodness that is and one can almost hear the predicted group sigh, but percolating right here amongst us, gives us good reason from that comes open discussion. -

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials -

District Directory 2003-2004

Handbook and Directory for Rotarians in District 9350 2017 – 2018 0 Rotary International President 2017-2018 Ian Riseley Ian H. S. Riseley is a chartered accountant and principal of Ian Riseley and Co., a firm he established in 1976. Prior to starting his own firm, he worked in the audit and management consulting divisions of large accounting firms and corporations. A Rotarian in the Rotary Club of Sandringham, Victoria, Australia since 1978, Ian has served Rotary as treasurer, director, trustee, RI Board Executive Committee member, task force member, committee member and chair, and district governor. Ian Riseley has been a member of the boards of both a private and a public school, a member of the Community Advisory Group for the City of Sandringham, and president of Beaumaris Sea Scouts Group. His honors include the AusAID Peacebuilder Award from the Australian government in 2002 in recognition of his work in East Timor, the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to the Australian community in 2006, and the Regional Service Award for a Polio-Free World from The Rotary Foundation. Ian and his wife, Juliet, a past district governor, are Multiple Paul Harris Fellows, Major Donors, and Bequest Society members. They have two children and four grandchildren. Ian believes that meaningful partnerships with corporations and other organizations are crucial to Rotary’s future. “We have the programs and personnel and others have available resources. Doing good in the world is everyone’s goal. We must learn from the experience of the polio eradication program to maximize our public awareness exposure for future partnerships. -

Newsletter No. 42

NEWSLETTER 42 2014/15 tO OUR www.abalimi.org.za Co-ordinating Office:c\o The Business Place Philippi, Cwango Crescent (Cnr New www.harvestofhope.co.za Eisleben Rd and Lansdowne Rd, behind Shoprite Centre) Philippi, 7785, Cape Town, FRIENDS www.farmgardentrust.org PO Box 44, Observatory, 7935. 021 3711653 Fax: 086 6131178 Khayelitsha Garden Centre 021 3613497 Nyanga Garden Centre 021 3863777 Seeds grow and become seedlings, which become tasty mama pat PaSses FlAme nutritious vegetables. Seeds also give birth to other seeds and so keep going the magic To her graNddaughteR cycle of life. a larger micro-farm soon. Zandile is proud of her first harvest for HoH (Harvest of Hope) last September. She attended the training of ABALIMI and then took the course of Applied Permaculture Training at SEED. “I am happy to be part of the community of ABALIMI farmers. I know that ABALIMI wants more young people as farmers and I am proud to be part of this new young micro- farming generation” she said. Her grandmother, Mama Patricia Palishe, is her inspiration. Mama Pat has her own garden in Khayelitsha which keeps her healthy and active. mama paT “I don’t want to stay sitting at home. I need ZaNDIlE to keep moving, wake up in the morning and always be fresh up. I do not sit and wait for death!” ABALIMI BEZEKHAYA inspires the Youth to take up the farming life just like their elders did before them. Hard work does not put off The two women often work together in Mama Pat’s garden and also the ambitious young women and men that now come to train to be help out in the HoH packshed. -

Infrastructure Plans 2016-17

TEMPLATE 1: SCHEDULE OF ACCOMMODATION REQUIREMENTS PER BUDGET PROGRAMME OBJECTIVE USER DEPARTMENT: EDUCATION MISSION: WCED HOW CAN THE PROVISION OF ACCOMMODATION CONTRIBUTE TOWARDS THIS VISION? To ensure that all the conditions for optimal lifelong learning are met in order for all learners to acquire the knowledge, skills and values they need to realise their potential, to lead fulfilling lives, to contribute to social and economic development PROGRAMME OUTCOMES OPTIMAL SUPPORTING ACCOMMODATION RATIONALE Programme 8.1: Administration To 8.1.1: Office of the MEC Additional office accommodation in Head Office, Office accommodation is required for staff in order provide overall management of and support to To provide for the functioning of the office of the Member of the Executive District Offices and Service Points are required to to execute their management and administration the education systems in accordance with the Council (MEC) for education accommodate expansion of organisational structure functions in support of provisioning of quality National Education Policy Act, Public Finance 8.1.2: Corporate Services education Management Act and other relevant policies. To provide management services that are not education specific for the education system, to make limited provision for and accommodation needs 8.1.3: Education Management To provide education management services for the education system 8.1.4: Human Resources Development To provide human resource development for office-based staff 8.1.5: Education Management Information System -

Curriculum GET

Directorate: Curriculum GET Reference: 20191107-1362 File no.: 12/16/7/1 Enquiries: A du Toit Curriculum GET Minute: DCG 0016/2019 To: Deputy Directors-General, Chief Directors, Directors, Heads: Curriculum Support, Circuit Managers, Deputy Chief Education Specialists, Foundation Phase Subject Advisers, Principals and Departmental Heads of ordinary public schools Subject: Jolly Phonics programme for English Home Language 1. The 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) results indicated that 78% of Grade 4 learners cannot read for meaning. The Western Cape Education Department (WCED) therefore developed a reading strategy to strengthen reading with comprehension in the province. 2. In 2019, the Jolly Phonics programme, in collaboration with Jolly Learning and Universal Learning Solutions, was piloted by the WCED in 42 schools (phase 1) across all eight districts. 3. In 2020, the WCED will roll out the programme to all English Home Language schools/classes in the Foundation Phase (FP) (see Annexure A). 4. The purpose of the programme is to strengthen reading and comprehension in English Home Language in the FP. 5. This minute serves to notify schools that they will be included in phase 2 of the programme. 6. Jolly Phonics training for phase 2 schools will take place on 13 and 14 January 2020. 7. The duration of the training is approximately two days. All teachers teaching English Home Language in the FP are required to attend the training. A separate training session will take place for all School Management Team members to familiarise them with the programme. Lower Parliament Street, Cape Town, 8001 Private Bag X9114, Cape Town, 8000 Tel: +27 21 467 2172 Fax: +27 21 483 7658 Employment and salary enquiries: 0861 92 33 22 Safe Schools: 0800 45 46 47 www.westerncape.gov.za 8. -

Tra 1 9 7 6 1 1 2 2 . 0 2 6 . 0

COI=SSICIT -.OF - INPUIRY 1'-TTO THE RTICTSD I-T COI=SSICIT -.OF - INPUIRY 1'-TTO THE RTICTSD I-T __C S OI&Y 0 Im CF 1:71-1112 I'T .4 SOTL,-lPH A:?nTC VOLM-7 58 (PaEes 2 CG! 2242) ropilING SESSION 22nd ITOVEH:EER, 1976. COIYISSICN --OF -I'TQUIRY -INTO TIM RIOTS IT SOWETO Al'r Cr'-HER PL~ACES3 UT SOUTTH AFRICA NORUTNG SESSION 22nd NOMPM~ER. 1976. VOL~UMtE 5 (Pages 2 861 - 2942) - 2 861 - DUGGAN. THE COMISSION REST2ES ON THE 22nd NOVEMBER, 1976. DR YUTAR: My first witness this morning, M'Lord, is Mr Alan Duggan and I hand in four copies of his memorandum. ALAN JOI2T DUGGAN: sworn states: DR YUTAR: You are a reporter and a member of the editorial staff of the Cape Times. -- That is true. In an endeavour to assist the Commission you have very kindly drawn up a short memorandum for the benefit of the Commission. -- That is right. You have a copy of it before you? -- I do. (10) And you are going to refer to certain clippings and in particular to one which you will read out, which you now formally hand in as EXHIBIT 180. That is the only copy we have at the moment. Just keep it until we have a duplicate made of it in due course. -- Right. You seem to have covered the riots over a long period, commencing the 4th August until the 12th October. -- That is right. And in Column A you list those reports which were written by you in their entirety. -

Icandelo Lokharityhulam Yeget

ICandelo loKharityhulam ye GET Isalathiso: 20191107-1362 Inombolo yefayili: 12/16/7/1 Imibuzo: A du Toit INgcaciso eMfutshane yeCandelo leKharityhulam ye -GET : DCG 0016/2019 Iya: KumaSekela Balawuli-Jikelele, kuBalawuli abaziiNtloko, kuBalawuli, kwiiNtloko zoQuquzelelo neNgcebiso ngezeKharityhulam, kuBaphathi beeSekethe, kumaSekela eeNgcali zeMfundo eziziiNtloko, kuBacebisi beZifundo beSigaba seSiseko, kwiiNqununu nakwiiNtloko zeZifundo zezikolo zikarhulumente eziqhelekileyo ISihloko: Iprogram ye-Jolly Phonics yesiNgesi uLwimi lokuQala 1. Iziphumo zophononongo lwe-Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) luka-2016 zichaze ukuba i-78% yabafundi beBakala 4 ayikwazi ukufunda iyiqonde intsingiselo. ISebe leMfundo leNtshona Koloni ( WCED) ke ngoko lenze isicwangciso sokufunda ukomeleza ukufunda nokuqonda intsingiselo apha kweli phondo. 2. Ngo-2019, iprogram eyi-Jolly Phonics programme , ibambisene ne-Jolly Learning and Universal Learning Solutions , yalingwa liSebe i WCED kwizikolo eziyi-42 (isigaba 1) kwizithili ezisibhozo ngokubanzi. 3. Ngo-2020, iSebe i WCED liya kuqalisa iprogram kwizikolo/kwiiklasi zesiNgesi uLwimi lweeNkobe kwiSigaba seSiseko ( Foundation Phase (FP ) (Makujongwe kwisiHlomelo A) 4. Injongo yale program kukomeleza ukufunda nokuqonda intsingiselo kwisiNgesi uLwimi lweeNkobe kwiSigaba seSiseko. 5. Injongo yale ngcaciso imfutshane kukwazisa izikolo ukuba ziya kubandakanywa kwisigaba 2 sale program. 6. Uqesesho lwe-Jolly Phonics lwezikolo zesigaba 2 luya kuqhubeka ngowe-13 nowe-14 kuJanuwari 2020. 7. Ithuba lokuqhuba koqeqesho liqikelelwa kwiintsuku ezimbini. Bonke ootitshala abafundisa isiNgesi uLwimi lweeNkobe kwiSigaba seSiseko kufuneka baye kuqeqesho. Iseshoni yoqeqesho eyahlukeneyo iya kuqhutyelwa onke amalungu eKomiti yoLawulo lweSikolo ukwenzela ukuba abe nolwazi ngale program. Lower Parliament Street, Cape Town, 8001 Private Bag X9114, Cape Town, 8000 Tel: +27 21 467 2172 Fax: +27 21 483 7658 Employment and salary enquiries: 0861 92 33 22 Safe Schools: 0800 45 46 47 www.westerncape.gov.za 8. -

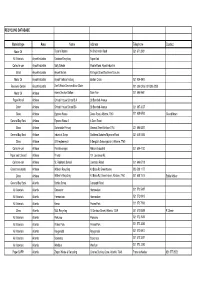

Region / Area Venue Schools Writing @ Venue # of Learners # Of

Region / Area Venue Schools Writing @ Venue # of Learners # of Schools @ Venue Outside SA OWN SCHOOL 1 WILLOW INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL( MATOLA) 14 1 OWN SCHOOL 2 WILLOW INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL(MAPUTO) 25 1 OWN SCHOOL 5 BIRLIK INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL 9 1 OWN SCHOOL 6 UBOMBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 6 1 OWN SCHOOL 7 EDUGATE ACADEMY 4 1 OWN SCHOOL 8 Privaatskool Moria 2 1 Gauteng 10064 VINEYARD CHRISTIAN COLLEGE 1 1 10067 WOODHILL COLLEGE 18 12566 PARVEEN HOME SCHOOL 2 PRETORIA EAST WOODHILL COLLEGE 4 11941 LORETO SCHOOL QUEENSWOOD 7 10512 WATERKLOOF PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 OWN SCHOOL 10131 ASTON MANOR 10 1 OWN SCHOOL 10133 AUCKLAND PARK PREPARATORY SCHOOL 45 1 OWN SCHOOL 10148 BENONI PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 1 OWN SCHOOL 10157 DAVEYTON INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL 12 1 OWN SCHOOL 10195 BROOKLYN PRIMARY 28 1 OWN SCHOOL 10199 BRYANSTON PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 1 OWN SCHOOL 10272 CRYSTAL PARK PRIMARY SCHOOL 1 1 OWN SCHOOL 10296 CURRO HAZELDEAN PRIVATE SCHOOL 54 1 OWN SCHOOL 10307 CAPITAL PARK PRIMARY SCHOOL 6 1 OWN SCHOOL 10315 CONFIDENCE COLLEGE (GOOD SAMARITAN) 20 1 OWN SCHOOL 10325 CORNWALL HILL COLLEGE 234 1 OWN SCHOOL 10353 BRESCIA HOUSE SCHOOL 85 1 OWN SCHOOL 10383 EASTLEIGH PRIMARY SCHOOL 3 1 OWN SCHOOL 10436 DAINFERN COLLEGE 76 1 OWN SCHOOL 10464 DC MARIVATE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL 1 1 OWN SCHOOL 10502 BISHOP BAVIN SCHOOL 9 1 OWN SCHOOL 10600 AL-ASR EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTE 4 1 OWN SCHOOL 10769 ST ANNES 38 1 OWN SCHOOL 10688 REDHILL PREP SCHOOL 44 1 OWN SCHOOL 10702 SAMA INDEPENDENT PRIMARY AND SECONDARY 36 1 OWN SCHOOL 10738 ST PAULUS LAERSKOOL 63 1 OWN SCHOOL 10817 ST JOHN'S PREPARATORY -

Final Spr 08 News.Qxd

spring 2008: volume 13, issue 1 newsletter of the myelodysplastic syndromes foundation From the Guest Editor’s Desk Flow Cytometry: Providing Additional Information in Diagnosis, Prognosis and Monitoring Treatment of MDS simultaneously along with light scattered by the cells as they traverse the laser light at rates of 500–1000 per second. The data generated by the flow cytometer can be analyzed by correlating the intensity of each dye along with cell size and cell granularity on each individual cell, Denise A. Wells, MD resulting in an identifying phenotype for that Contents Michael R. Loken, PhD cell. The cell surface proteins or antigens detected by monoclonal antibodies are the From the Operating Director’s Desk 5 Hematologics, Inc. Seattle, Washington final translated products of genes which are Young Investigator Grants Program 6 highly regulated during maturation from Flow cytometry is only beginning to be Foundation Initiatives 7 hematopoietic stem cells found in the bone used to study patients with MDS. We would marrow to fully functional mature cells Meeting Highlights/Announcements 8 like to provide background and an overview observed in peripheral blood. With proper of technology, and its basis for assessing Patient Services 11 selection of antibodies, and a careful multi- patients with MDS which will have dimensional analysis, it is possible to identify Patient Forums and Support Groups 12 increasing importance in the near future in every cell in a marrow aspirate specimen, Living With MDS 13 being able to separate MDS from