The Unending War? the Baltic States After 1918. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fontannikud Enamlaste Võitlussalga Lõhestajaina

Fontannikud enamlaste võitlussalga lõhestajaina Aarne Ruben Selles artiklis on vaatluse all lõhe Eesti kommunistide vahel, mille tekke- aeg ulatub juba I maailmasõja eelsetesse sündmustesse. Lõhe halvendas liikumise juhtide omavahelisi suhteid, raskendas põrandaalust võitlust vabariigi vastu ja seega enamlaste kavatsetud maailmarevolutsiooni- ürituse läbiviimist ning viis lõppkokkuvõttes paradoksaalsel kombel peaaegu kõigi asjaosaliste hävitamiseni peamiselt 1937. aastal. Erinevalt varem kirjutanud autorite käsitlustest pole siinse kirjutise põhirõhk aga mitte kommunistide intriigidel Leningradis ja Moskvas, vaid konspira- tiivses elus, reaalses võitluses Eesti Vabariigi vastu. Põrandaaluste kommunistide heitlust Eesti kaitsepolitseiga iseloo- mustab palju saladusi. Pöördelised hetked, nagu tulevahetus kommu- nistidega Tallinnas Jaama tänaval, Viktor Kingissepa äraandmine ja kättesaamine, Saku Võisilma talu salatrükikoja tabamine 1920. aastal, tulevahetus Kreuksiga ja tema tapmine – kõik need on leidnud oma koha rahva ajaloolises mälus. 2010. aastal ilmunud Reigo Rosenthali ja Marko Tammingu „Sõda pärast rahu. Eesti eriteenistuste vastasseis Nõukogude luure ja põrandaaluste kommunistidega 1920–1924“ ja Olaf Kuuli „Fon- tanka ja Moika vahel. Eesti kommunistide sisetülidest 1919–1938“ ning 2014. aastal ilmunud Jaak Valge „Punased I“ on avanud ajastu põhilisi probleeme.1 On oluline analüüsida Eestimaa Kommunistliku Partei (edaspidi EKP) Venemaa büroo fondis leiduvat kirjavahetust.2 Selles kirjavahetuses 1 Reigo Rosenthal ja Marko Tamming, -

RCS Demographics V2.0 Codebook

Religious Characteristics of States Dataset Project Demographics, version 2.0 (RCS-Dem 2.0) CODE BOOK Davis Brown Non-Resident Fellow Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion [email protected] Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following persons for their assistance, without which this project could not have been completed. First and foremost, my co-principal investigator, Patrick James. Among faculty and researchers, I thank Brian Bergstrom, Peter W. Brierley, Peter Crossing, Abe Gootzeit, Todd Johnson, Barry Sang, and Sanford Silverburg. I also thank the library staffs of the following institutions: Assembly of God Theological Seminary, Catawba College, Maryville University of St. Louis, St. Louis Community College System, St. Louis Public Library, University of Southern California, United States Air Force Academy, University of Virginia, and Washington University in St. Louis. Last but definitely not least, I thank the following research assistants: Nolan Anderson, Daniel Badock, Rebekah Bates, Matt Breda, Walker Brown, Marie Cormier, George Duarte, Dave Ebner, Eboni “Nola” Haynes, Thomas Herring, and Brian Knafou. - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Citation 3 Updates 3 Territorial and Temporal Coverage 4 Regional Coverage 4 Religions Covered 4 Majority and Supermajority Religions 6 Table of Variables 7 Sources, Methods, and Documentation 22 Appendix A: Territorial Coverage by Country 26 Double-Counted Countries 61 Appendix B: Territorial Coverage by UN Region 62 Appendix C: Taxonomy of Religions 67 References 74 - 2 - Introduction The Religious Characteristics of States Dataset (RCS) was created to fulfill the unmet need for a dataset on the religious dimensions of countries of the world, with the state-year as the unit of observation. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’. -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

Michael H. Clemmesen Version 6.10.2013

Michael H. Clemmesen Version 6.10.2013 1 Prologue: The British 1918 path towards some help to Balts. Initial remarks to the intervention and its hesitant and half-hearted character. It mirrored the situation of governments involved in the limited interventions during the last In the conference paper “The 1918-20 International Intervention in the Baltic twenty years. Region. Revisited through the Prism of Recent Experience” published in Baltic Security and Defence Review 2:2011, I outlined a research and book project. The This intervention against Bolshevik Russia and German ambitions would never Entente intervention in the Baltic Provinces and Lithuania from late 1918 to early have been reality without the British decision to send the navy to the Baltic 1920 would be seen through the prism of the Post-Cold War Western experience Provinces. The U.S. would later play its strangely partly independent role, and the with limited interventions, from Croatia and Bosnia to Libya, motivated by the operation would not have ended as it did without a clear a convincing French wish to build peace, reduce suffering and promote just and effective effort. However, the hesitant first step originated in London. government. This first part about the background, discourse and experience of the first four months of Britain’s effort has been prepared to be read as an independent contribution. However, it is also an early version of the first chapters of the book.1 It is important to note – especially for Baltic readers – that the book is not meant to give a balanced description of what we now know happened. -

Volume 66: Number 2, 2020: Summary

International Affairs: Volume 66: Number 2, 2020: Summary. Sergey Lavrov Turns 70. International Affairs Editorial Board and Staff Members. Dear Sergey Viktorovich, Staff members of the International Affairs journal are sending their sincere, heartfelt wishes on your birthday. We are genuinely proud of the fact that for many years (far from the easiest ones in the history of Russia and humankind), the International Affairs Board has been headed by a Russian politician and statesman such as you. Your diplomatic talent, reinforced by your professionalism, will to victory and sometimes unconventional decisions, give confidence that Russia will pass through this zone of turbulence, the times of arbitrary rules, not international laws, and the sanctions chaos in international relations and will emerge as a model of stability and a sought-after world arbiter. We are grateful that, despite your superhuman schedule of meetings and trips, addressing priority international issues in real time and sometimes actually saving the world, you find an opportunity to get your articles published in our journal and become involved in our projects. This is very important to us. We hope that this will continue to be the case in the future. We wish you good health, well-being and many more years at the service of our Motherland. To Provide Strategic Stability and Form a Just World Order. Vladimir Putin, President of the Russian Federation. DEAR FRIENDS, Let me extend my heartfelt wishes on your professional holiday, Diplomats’ Day. Russian diplomats have always resolutely and consistently defended the interests of our Fatherland. While continuing the glorious traditions of our predecessors, you carry out your duty with honor and deal with challenging and responsible foreign policy tasks. -

C:/Users/User/Desktop/2017-08-16 Tannenberg Booklet 6 Seiten BGG

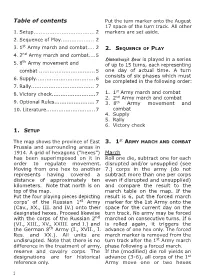

Table of contents Put the turn marker onto the August 17 space of the turn track. All other 1. Setup................................... 2 markers are set aside. 2. Sequence of Play................... 2 st 3. 1 Army march and combat.... 2 2. SEQUENCE OF PLAY 4. 2nd Army march and combat....5 th Hindenburg’s Hour is played in a series 5. 8 Army movement and of up to 15 turns, each representing combat ................................ 5 one day of actual time. A turn consists of six phases which must 6. Supply..................................6 be completed in the following order: 7. Rally.................................... 7 st 8. Victory check.........................7 1. 1 Army march and combat 2. 2nd Army march and combat 9. Optional Rules....................... 7 3. 8th Army movement and 10. Literature............................ 7 combat 4. Supply 5. Rally 6. Victory check 1. SETUP The map shows the province of East 3. 1st ARMY MARCH AND COMBAT Prussia and surrounding areas in 1914. A grid of hexagons (“hexes”) March has been superimposed on it in Roll one die, subtract one for each order to regulate movement. disrupted and/or unsupplied (see Moving from one hex to another 7.) corps in the army (do not represents having covered a subtract more than one per corps distance of approximately ten even if disrupted and unsupplied) kilometers. Note that north is on and compare the result to the top of the map. march table on the map. If the Put the four playing pieces depicting result is 6, put the forced march corps’ of the Russian 1st Army marker for the 1st Army onto the (Cav., XX., III. -

Ronald Macarthur Hirst Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4f59r673 No online items Register of the Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Processed by Brad Bauer Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Ronald MacArthur 93044 1 Hirst papers Register of the Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Brad Bauer Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Elizabeth Konzak and David Jacobs © 2008 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers Dates: 1929-2004 Collection number: 93044 Creator: Hirst, Ronald MacArthur, 1923- Collection Size: 102 manuscript boxes, 4 card files, 2 oversize boxes (43.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: The Ronald MacArthur Hirst papers consist largely of material collected and created by Hirst over the course of several decades of research on topics related to the history of World War II and the Cold War, including the Battle of Stalingrad, the Allied landing at Normandy on D-Day, American aerial operations, and the Berlin Airlift of 1948-1949, among other topics. Included are writings, correspondence, biographical data, notes, copies of government documents, printed matter, maps, and photographs. Physical location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English, German Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copiesof audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. -

Tanel Rander, Aarne Ruben

was quite lately understood as “extraterrestrial”. THE POWER OF Mass culture embodied the geopolitical turn and empowered itself through everlasting NOSTALGIA contemporaneity – the era, where ideology and history had ceased to exist. A new subjectivity Tanel Rander started to sprout everywhere – millions of people with identical desires, millions of new global citizens had emerged. For them globality started WHO OWNS MY SUBJECTIVITY1? from the first border control between the East and the West. Last autumn I participated in the conference “Communist Nostalgia” in the University of I was one of such subjectivities. To me the 90s Glasgow, where, during public discussion, an meant teenage – the most receptive age of being American lady made a remark like this: open to ideology. Music defined my relation with the world outside. Music was like a protective “It would be really bizarre if East layer that saved me from the brutal reality that Europeans would be nostalgic like I could never identify with. I lived deep inside of us, for the late 80s and early 90s, my imagination, as teenagers often do. My long I mean grunge music, Kurt Cobain, etc. hair made me withstand constant harassments It would be really, really bizarre!”. that came from everywhere, except my family and few friends. I spent a lot of time watching I felt personally touched, as precisely this era MTV and playing Nirvana songs on guitar. and these keywords played important role in I used to daydream of Seattle – I imagined the formation of my subjectivity. Nostalgia is rather Annelinn block houses into Seattle skyline. -

Russia's Imperial Encounter with Armenians, 1801-1894

CLAIMING THE CAUCASUS: RUSSIA’S IMPERIAL ENCOUNTER WITH ARMENIANS, 1801-1894 Stephen B. Riegg A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Louise McReynolds Donald J. Raleigh Chad Bryant Cemil Aydin Eren Tasar © 2016 Stephen B. Riegg ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Stephen B. Riegg: Claiming the Caucasus: Russia’s Imperial Encounter with Armenians, 1801-1894 (Under the direction of Louise McReynolds) My dissertation questions the relationship between the Russian empire and the Armenian diaspora that populated Russia’s territorial fringes and navigated the tsarist state’s metropolitan centers. I argue that Russia harnessed the stateless and dispersed Armenian diaspora to build its empire in the Caucasus and beyond. Russia relied on the stature of the two most influential institutions of that diaspora, the merchantry and the clergy, to project diplomatic power from Constantinople to Copenhagen; to benefit economically from the transimperial trade networks of Armenian merchants in Russia, Persia, and Turkey; and to draw political advantage from the Armenian Church’s extensive authority within that nation. Moving away from traditional dichotomies of power and resistance, this dissertation examines how Russia relied on foreign-subject Armenian peasants and elites to colonize the South Caucasus, thereby rendering Armenians both agents and recipients of European imperialism. Religion represented a defining link in the Russo-Armenian encounter and therefore shapes the narrative of my project. Driven by a shared ecumenical identity as adherents of Orthodox Christianity, Armenians embraced Russian patronage in the early nineteenth century to escape social and political marginalization in the Persian and Ottoman empires. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website.