Projector Phone Use: Practices and Social Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

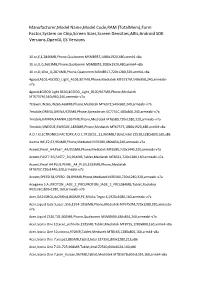

Totalmem),Form Factor,System on Chip,Screen Sizes,Screen Densities,Abis,Android SDK Versions,Opengl ES Versions

Manufacturer,Model Name,Model Code,RAM (TotalMem),Form Factor,System on Chip,Screen Sizes,Screen Densities,ABIs,Android SDK Versions,OpenGL ES Versions 10.or,E,E,2846MB,Phone,Qualcomm MSM8937,1080x1920,480,arm64-v8a 10.or,G,G,3603MB,Phone,Qualcomm MSM8953,1080x1920,480,arm64-v8a 10.or,D,10or_D,2874MB,Phone,Qualcomm MSM8917,720x1280,320,arm64-v8a 4good,A103,4GOOD_Light_A103,907MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737M,540x960,240,armeabi- v7a 4good,4GOOD Light B100,4GOOD_Light_B100,907MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737M,540x960,240,armeabi-v7a 7Eleven,IN265,IN265,466MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6572,540x960,240,armeabi-v7a 7mobile,DRENA,DRENA,925MB,Phone,Spreadtrum SC7731C,480x800,240,armeabi-v7a 7mobile,KAMBA,KAMBA,1957MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,720x1280,320,armeabi-v7a 7mobile,SWEGUE,SWEGUE,1836MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737T,1080x1920,480,arm64-v8a A.O.I. ELECTRONICS FACTORY,A.O.I.,TR10CS1_11,965MB,Tablet,Intel Z2520,1280x800,160,x86 Aamra WE,E2,E2,964MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,480x854,240,armeabi-v7a Accent,Pearl_A4,Pearl_A4,955MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,720x1440,320,armeabi-v7a Accent,FAST7 3G,FAST7_3G,954MB,Tablet,Mediatek MT8321,720x1280,160,armeabi-v7a Accent,Pearl A4 PLUS,PEARL_A4_PLUS,1929MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6737,720x1440,320,armeabi-v7a Accent,SPEED S8,SPEED_S8,894MB,Phone,Mediatek MT6580,720x1280,320,armeabi-v7a Acegame S.A. -

Ams Second Quarter and Half Year Results 2020

ams Second quarter and half year results 2020 Alexander Everke, CEO Ingo Bank, CFO Moritz M. Gmeiner, Head of IR July 2020 Vision for ams/OSRAM Create the uncontested leader in optical solutions Sensing Illumination Visualization © ams AG Page 2 Build the leading portfolio in optical solutions Strength across the full range of key solution components Optical components Integrated circuits Emitters Detectors + micro-modules + algorithms • LEDs • Optical elements: Lenses, • Light sensors • Emitter driver ICs Key solution • µLED light guides, DOEs • Bio-sensors • Sensor interfaces components • VCSELs/EELs • Micro-optical packaging • Image sensors • Sensor processors • Lamps • Optical modules (incl. algorithms) Micro-optical/optical solutions + lamps (modules) Sensing Illumination Visualization Target applications © ams AG Page 3 Create the uncontested leader in optical solutions Micromodule + module Innovation + leadership Diversified business solutions Pursue real innovation and Develop optical micromodule/module Drive diversified business with market leadership in key optical solutions for growth applications in balanced application mix components (emitters, optics, sensing, illumination, visualization and broad customer portfolio detectors, ICs, algorithms) Co-operation In-house manufacturing M&A Work with innovation leaders Focus in-house manufacturing Accelerate the implementation in each area, then roll out to on process steps driving of our strategy through M&A broader customer base product differentiation Leading financial performance Deliver excellent financial performance in revenue growth and profitability © ams AG Page 4 Strategic position to benefit from growth trends Key technology trends driving the sensing market Digital Next generation Autonomous Next generation In-cabin sensing automotive Bio-sensing Industrial IoT displays driving imaging (ICS) / HMI lighting . µLED displays . LIDAR solutions . -

Announcement

Announcement Total 83 articles, created at 2016-04-13 06:03 1 Facebook levels up its live streaming service with new video tab and developer tools (3.00/4) Facebook is doubling down on its investment in video with a new tool that will help hardware makers build devices to stream live to the social networking service. 2016-04-12 14:42 3KB www.computerworld.com 2 Show us your Dark Souls 3 character Day one in Lothric: took a sick selfie. 2016-04-13 01:04 962Bytes www.pcgamer.com (2.00/4) 3 Smite fans, we've got 5,000 Jing Wei keys to give away (2.00/4) That's a lot of codes. 2016-04-13 00:37 1KB www.pcgamer.com 4 Badlock: Patch your Samba and Windows server now The Badlock security holes are as bad as bad can be. You should patch your Samba- and Windows-servers immediately. 2016-04-12 19:41 4KB zdnet.com.feedsportal.com (2.00/4) 5 PC shipments decline for sixth consecutive quarter, but gaming PCs are on the rise Industry tracking firms Gartner and IDC both reported steep declines in worldwide PC (2.00/4) shipments. 2016-04-12 18:08 3KB www.pcgamer.com 6 Come in Microsoft SQL Server 2005, your time is up Another ageing but still used Microsoft product put out to pasture 2016-04-12 15:37 2KB www.theinquirer.net (2.00/4) 7 Apple Pay struggles in Australia as banks profit from a fee- phobic market Australia's big banks are not rushing to enable Apple Pay despite the country's citizens using iPhones at a rate more than double the global average. -

Pico-Ing Into the Future of Mobile Projection and Contexts

Pico-ing into the Future of Mobile Projection and Contexts Max L. Wilson*, Dan Craggs, Simon Robinson, Matt Jones, Kristian Brimble Future Interaction Technology Lab, Department of Computer Science, Swansea University, Swansea, SA28PP, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1792 295393 Fax: +44 (0) 1792 295708 {m.l.wilson, csdanc, s.n.w.robinson, matt.jones}@swansea.ac.uk Abstract Ten years ago we were on the verge of having cameras built into our mobile phones, but knew very little about what to expect or how they would be used. Now we are faced with the same unknowns with mobile projector phones. This research seeks to explore how people will want to use such technology, how they will feel when using it, and what social effects we can expect to see. This paper describes our two-phase field investigation that uses a combination of methods to investigate how, when, and why mobile projections may be used. The first study used an experience sampling method to investigate responses to a range of different media types, and, for example, the choice of surfaces used in each case. The second study asked users to create video diary entries showing when, where, and why they would have wanted to project information. Together these studies provide complementary insights into the future use of mobile projector phones. Our results cover detailed responses to a range of media types from the first study, while the second identified which of the known mobile information needs were commonly recorded by participants. Both studies provide insights that may help shape the hardware, software, and interaction design of mobile projector phones as they become increasingly available. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT This annual report (in both English and Chinese versions) has been posted on the Company’s website at www.mi.com and the Stock Exchange’s website at www.hkexnews.hk. Shareholders who have chosen to rely on copies of the corporate communications (including but not limited to annual report and (where applicable) summary financial report, interim report and (where applicable) summary interim report, notice of meeting, listing document, circular and proxy form) posted on the aforesaid websites in lieu of any or all the printed copies thereof may request the printed copy of the annual report. Shareholders who have chosen or are deemed to have consented to receive the corporate communications using electronic means and who have difficulty in receiving or gaining access to the annual report posted on the Company’s website will promptly upon request be sent the annual report in printed form free of charge. Shareholders may at any time choose to change their choice of means of receipt (in printed form or by electronic means through the Company’s website) and language (in English only, in Chinese only or in both Chinese and English) of all future corporate communications from the Company by sending reasonable prior notice in writing by post to the Hong Kong Share Registrar at 17M Floor, Hopewell Centre, 183 Queen’s Road East, Wan Chai, Hong Kong or by email at [email protected]. CONTENTS OPEN LETTER FROM OUR CHAIRMAN 4 CORPORATE INFORMATION 8 FIVE-YEAR FINANCIAL SUMMARY 10 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT -

Mobile Interaction with the Real World

Mobile Interaction with the Real World Dr. Enrico Rukzio Lecturer in Mobile HCI Computing Department Lancaster University (UK) Outline • Mobile interaction with the real world – Overview, related research areas, classification • Focus on – Touching (NFC based interaction techniques) – Pointing (personal projectors) – Scanning and user mediated object selection • Application areas • Summary & Conclusion 2 Mobile Interaction with the Real World sensors in mobile device interaction with augmented and not augmented “things” Exchange (images, audio files, messages), to {call, text, play, Play (mobile gaming) surf the internet}, PIM proximity of users Location based services (e.g. tour guide, city guide, mobile navigation) [Kindberg et al. 2002, Rukzio 2007] Related Research Areas R R R C C Before the computer Usage of everyday computers Virtual Reality (laptop, mobile phone) R R R C C C C C C Ubiquitous Computing Mobile Interaction Mobile Augmented Reality (Real World Computer) with the Real World C – Computer Human – Computer - Interaction R – Real World Human – Real World - Interaction Real World – Computer - Interaction [Rukzio 2007] based on Computer – Computer - Interaction [Rekimoto and Nagao 1995] Mobile Interaction with the Real World: Interaction Techniques Interaction Touching Pointing Scanning User-mediated Indirect Remote technique object interaction Controls Description The user touches The user points A link between The user types in The user controls a smart object on a smart mobile device and information a remote display with a mobile object with a smart object is provided by the with a mobile device to mobile device to established object to establish device. establish a link. establish a link. because of their a link between proximity. -

Prime - Projected Interface for Mobile Electronics

CS Department, Duke University & ECE Department, Duke University PrIME - Projected Interface for Mobile Electronics Joe Levy Vansh Muttreja Naveen Santhapuri Romit Roy Choudhury April 2, 2012 Contents 1 Abstract 3 2 Introduction 3 3 Background and Related Work 4 4 Comparison with Related Work 5 5 How it Works 6 5.1 Use from the User's Perspective . 6 5.2 Prototype Model . 6 5.3 Calibration . 8 5.4 Post Calibration . 8 6 PrIME-Based Smartphone Applications 9 6.1 Virtual White Board . 9 6.2 Dynamic Presentation . 10 6.3 Fruit Ninja Adaptation . 12 7 Performance 12 7.1 Speed of Calibration . 13 7.2 Accuracy of Calibration . 14 7.3 Reaction Time . 16 7.4 Battery Usage . 18 8 Usability of PrIME in the Real World Outside of Pico-Projector Smartphones 19 9 PrIME's Ability to Help Make Smartphones the New Personal Computer 20 10 Future Work 20 11 Conclusions 21 List of Tables 1 Comparison of Ease of Use Between PrIME and Related Work . 6 2 PrIME Calibration Speed as a Function of Distance and Brightness . 13 1 3 PrIME Calibration Accuracy as a Function of Distance and Brightness . 15 4 Fruit Ninja Reaction Speed Over 1 Minute . 17 5 Dynamic Presentation Reaction Speed Over 1 Minute . 17 6 Fruit Ninja Battery Usage over Time . 18 7 Dynamic Presentation Battery Usage over Time . 18 List of Figures 1 Photographs of the prototype PrIME model from front and back . 7 2 Playing Tic-Tac-Toe between a computer and a phone on Virtual White Board . 9 3 A sample presentation given using the Dynamic Presentation PrIME app . -

Umar Rashid Phd Thesis

CROSS-DISPLAY ATTENTION SWITCHING IN MOBILE INTERACTION WITH LARGE DISPLAYS Umar Rashid A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3193 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License Cross-Display Attention Switching in Mobile Interaction with Large Displays PhD Thesis by Umar Rashid School of Computer Science University of St Andrews March 2012 Abstract Mobile devices equipped with features (e.g., camera, network connectivity and media player) are increasingly being used for different tasks such as web browsing, document reading and photography. While the portability of mobile devices makes them desirable for pervasive access to information, their small screen real-estate often imposes restrictions on the amount of information that can be displayed and manipulated on them. On the other hand, large displays have become commonplace in many outdoor as well as indoor environ- ments. While they provide an efficient way of presenting and disseminating information, they provide little support for digital interactivity or physical accessibility. Researchers argue that mobile phones provide an efficient and portable way of interacting with large displays, and the latter can overcome the limitations of the small screens of mobile devices by providing a larger presentation and interaction space. However, distributing user inter- face (UI) elements across a mobile device and a large display can cause switching of visual attention and that may affect task performance. -

2019 Annual Report 3

2019 2019 ANNUAL REPORT This annual report (in both English and Chinese versions) has been posted on the Company’s website at www.mi.com and the Stock Exchange’s website at www.hkexnews.hk. Shareholders who have chosen to rely on copies of the corporate communications (including but not limited to annual report and (where applicable) summary financial report, interim report and (where applicable) summary interim report, notice of meeting, listing document, circular and proxy form) posted on the aforesaid websites in lieu of any or all the printed copies thereof may request the printed copy of the annual report. Shareholders who have chosen or are deemed to have consented to receive the corporate communications using electronic means and who have difficulty in receiving or gaining access to the annual report posted on the Company’s website will promptly upon request be sent the annual report in printed form free of charge. Shareholders may at any time choose to change their choice of means of receipt (in printed form or by electronic means through the Company’s website) and language (in English only, in Chinese only or in both Chinese and English) of all future corporate communications from the Company by sending reasonable prior notice in writing by post to the Hong Kong Share Registrar at 17M Floor, Hopewell Centre, 183 Queen’s Road East, Wan Chai, Hong Kong or by email at [email protected]. CONTENTS OPEN LETTER FROM OUR CHAIRMAN 4 CORPORATE INFORMATION 8 FIVE-YEAR FINANCIAL SUMMARY 10 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 12 MANAGEMENT -

A Mobile Focus + Context System

MOBILE FOCUS + CONTEXT: EXPLORING THE COMBINATION OF LARGE OVERVIEWS WITH HIGH-RESOLUTION DETAILS IN DYNAMIC, MOBILE WORK ENVIRONMENTS by Majid Nasirinejad Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Computer Science at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2016 © Copyright by Majid Nasirinejad, 2016 DEDICATION PAGE Everything in the universe is within you. Ask all from yourself. ~Rumi, 1759 Divan-e Shams ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................viii ABSTRACT ............................................................................... xii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED...............................................xiii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................... xiv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................. 1 1.1 Contributions .................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Structure of the thesis ....................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 2 RELATED WORK / LITERATURE REVIEW ............. 8 2.1 Information Display ......................................................................................... 8 2.1.1 Portability ............................................................................................ 8 2.1.2 Screen size ......................................................................................... -

Search Light Interactions with Personal Projector

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lancaster E-Prints Search Light Interactions with Personal Projector Andrew Molineux, Enrico Rukzio, Andrew Greaves Computing Department, Lancaster University, UK {molineux, rukzio, greaves}@comp.lancs.ac.uk ABSTRACT 2. RELATED WORK Mobile projectors are an emerging trend and becoming ever more Greaves et al. [3,4] created a prototype for using mobile projectors present in the consumer market. One main concern is how this to browse an image library. The three potential interactions were resource will be used and exploited. The act of physically holding phone screen only, projector only and a combination of phone and the projection device while interacting is uncommon and projector. Tests showed that the users predominantly preferred the potentially beset with many issues. In this paper we present a projection only method and half of the participants agreed that the mobile application, which uses the searchlight metaphor as a projection only technique was the fastest. The problem of context novel means of navigating though information space, potentially switches is common in both the projection only and the mixed of limitless size. In addition to the searchlight navigation screen technique as the user still had to use the phone keypad to technique we have developed a number of input techniques which navigate. challenge the classic button press interaction with a number of Cao et al. [5] devised a multiuser interaction space using handheld intuitive gestures which complement the interaction style. We projectors and a searchlight metaphor to navigate within the present our findings from a user study in which the usability of application. -

Investor Presentation

ams First quarter results 2020 Alexander Everke, CEO Michael Wachsler-Markowitsch, CFO Moritz M. Gmeiner, Head of IR April 2020 Legal disclaimer These materials and information constitute neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to buy securities according to the European Prospectus Regulation (EU) 2017/1129 or other applicable laws. These materials and information do not constitute or form a part of any offer or solicitation to purchase or subscribe for securities in the United States of America, Australia, Canada or Japan, or any other jurisdiction in which such offer or solicitation may be unlawful. The ams AG securities described herein have not been and will not be registered under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the "Securities Act") or under any securities laws of any state or other jurisdiction of the United States and may not be offered, sold, taken up, exercised, resold, renounced, transferred or delivered, directly or indirectly, within the United States except pursuant to an applicable exemption from, or in a transaction not subject to, the registration requirements of the Securities Act and in compliance with any applicable securities laws of any state or other jurisdiction of the United States. These materials and information constitute neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to buy securities and does not constitute a prospectus according to Articles 35 et seqq. of the Swiss Financial Services Act (“FinSA”) or Articles 652a and 1156 of the Swiss Code of Obligations (as such articles were in effect immediately prior to the entry into effect of FinSA) or Article 27 et seqq.