Institute of Commonwealth Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Racialism, Non-Collaboration and Communism in South Africa

Non-racialism, non-collaboration and Communism in South Africa: The contribution of Yusuf Dadoo during his exile years (1960-1983) Paper presented at the Conference on ‘Yusuf Dadoo, 1909-2009: Marxism, non-racialism and the shaping of the South African liberation struggle’ University of Johannesburg, 4-5 September 2009 Allison Drew Department of Politics University of York, UK It has often been argued by our opponents that Communism was brought to our country by whites and foreigners, that it is an alien importation unacceptable to the indigenous majority. Our reply to this is that the concept of the brotherhood of man, of the sharing of the fruits of the earth, is common to all humanity, black and white, east and west, and has been formulated in one form or another throughout history (Yusuf Dadoo, 1981).1 This paper examines Yusuf Dadoo’s contribution to the thinking and practice of non- racialism during his years in exile. Non-racialism refers to the rejection of racial ideology − the belief that human beings belong to different races. Instead, it stresses the idea of one human race. Organizationally, it implies the recruitment of individual members without regards to colour, ethnic or racial criteria. Non-racialism has long been a subject of debate on the South African left as socialists struggled with the problems of how to organize political movements in a manner that did not reinforce state-imposed racial and ethnic divisions and promote non-racialism in conditions of extremes racial inequality. The South African Communist Party (SACP) was formed in 1953 as a clandestine body that prioritized alliance politics over the development of an independent profile. -

South Africaâ•Žs Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography Volume 6 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Article 1 Towards Africa 2-6-2001 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.uiowa.edu/ejab Part of the African History Commons, and the African Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Pfister, Roger (2001) "South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa," Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography: Vol. 6 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17077/1092-9576.1003 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 6 (2000) South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister, Centre for International Studies, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Preface 1. Introduction Two principal factors have shaped South Africa’s post-apartheid foreign policy towards Africa. First, the termination of apartheid in 1994 allowed South Africa, for the first time in the country’s history, to establish and maintain contacts with African states on equal terms. Second, the end of the Cold War at the end of the 1980s led to a retreat of the West from Africa, particularly in the economic sphere. Consequently, closer cooperation among all African states has become more pertinent to finding African solutions to African problems. -

Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo

YUSUF MOHAMED DADOO SOUTH AFRICA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE Statements, Speeches and Articles including Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi Compiled and edited by E. S. Reddy With a foreword by Shri R. Venkataraman President of India Namedia Foundation STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED New Delhi, 1990 [NOTE: A revised and expanded edition of this book was published in South Africa in 1991 jointly by Madiba Publishers, Durban, and UWC Historical and Cultural Centre, Bellville. The South African edition was edited by Prof. Fatima Meer. The present version includes items additional to that in the two printed editions.] FOREWORD TO THE INDIAN EDITION The South African struggle against apartheid occupies a cherished place in our hearts. This is not just because the Father of our Nation commenced his political career in South Africa and forged the instrument of Satyagraha in that country but because successive generations of Indians settled in South Africa have continued the resistance to racial oppression. Hailing from different parts of the Indian sub- continent and professing the different faiths of India, they have offered consistent solidarity and participation in the heroic fight of the people of South Africa for liberation. Among these brave Indians, the name of Dr. Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo is specially remembered for his remarkable achievements in bringing together the Indian community of South Africa with the African majority, in the latter's struggle against racism. Dr. Dadoo met Gandhiji in India and was in correspondence with him during a decisive phase of the struggle in South Africa. And Dr. Dadoo later became an esteemed colleague of the outstanding South African leader, Nelson Mandela. -

Author Accepted Manuscript

University of Dundee Campaigning against apartheid Graham, Matthew Published in: Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2018.1506871 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Graham, M. (2018). Campaigning against apartheid: The rise, fall and legacies of the South Africa United Front 1960-1962. Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 46(6), 1148-1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2018.1506871 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Campaigning against apartheid: The rise, fall and legacies of the South Africa United Front 1960- 1962 Matthew Graham University of Dundee Research Associate at the International Studies Group, University of the Free State, South Africa Correspondence: School of Humanities, University of Dundee, Nethergate, Dundee, DD1 4HN. [email protected] 01382 388628 Acknowledgements I’d like to thank the anonymous peer-reviewers for offering helpful and constructive comments and guidance on this article. -

Mayor of Joburg, India's Republic Day Celebration

SPEECH BY CLR MPHO PARKS TAU, EXECUTIVE MAYOR OF JOHANNESBURG, INDIA’S REPUBLIC DAY CELEBRATION, HOUGHTON, JOHANNESBURG, 26 JANUARY, 2014 Your Excellency, Honourable High Commissioner of India, Ms. Ruchi Ghanashyam Consul General Mr. Randhir Jaiswal High Commissioners, Ambassadors, and other Members of the Diplomatic Corps, Officials from the City of Johannesburg Ladies and gentlemen Good Evening As the Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg I would like to thank the Indian government, through you, your Excellency the High Commissioner of India, Ms. Ruchi Ghanashyam, for inviting us to this important function, commemorating the day in which the Constitution of India came into force on 26 January 1950. This is an important day in India’s political calendar. On this day, the people of India finally freed themselves from the clutches of colonialism, following independence in 1947. As South Africans we identify with your struggle for freedom and draw our own parallels with the course of events in India. For us, your 26 January is the symbolic equivalent of our April 27, the day on which we liberated ourselves from neo- colonialism, following almost 300 years of racial oppression. The day is also equivalent to May 28, 1996 when as South Africa we adopted what 1 came to be known as the most liberal constitution in the world. Indian independence was undoubtedly one of the most crucial events in the past several generations: world-wide, there were many struggles against imperialism thereafter, but with India a free nation, the writing was on the wall for empire in the post-war world. -

Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’S Religio-Political Thought

ISLAMIC LIBERATION THEOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA: FARID ESACK’S RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHT Yusuf Enes Sezgin A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Cemil Aydin Susan Dabney Pennybacker Juliane Hammer ã2020 Yusuf Enes Sezgin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Yusuf Enes Sezgin: Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’s Religio-Political Thought (Under the direction of Cemil Aydin) In this thesis, through analyzing the religiopolitical ideas of Farid Esack, I explore the local and global historical factors that made possible the emergence of Islamic liberation theology in South Africa. The study reveals how Esack defined and improved Islamic liberation theology in the South African context, how he converged with and diverged from the mainstream transnational Muslim political thought of the time, and how he engaged with Christian liberation theology. I argue that locating Islamic liberation theology within the debate on transnational Islamism of the 1970s onwards helps to explore the often-overlooked internal diversity of contemporary Muslim political thought. Moreover, it might provide important insights into the possible continuities between the emancipatory Muslim thought of the pre-1980s and Islamic liberation theology. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to many wonderful people who have helped me to move forward on my academic journey and provided generous support along the way. I would like to thank my teachers at Boğaziçi University from whom I learned so much. I was very lucky to take two great courses from Zeynep Kadirbeyoğlu whose classrooms and mentorship profoundly improved my research skills and made possible to discover my interests at an early stage. -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture

The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture Contents Page 3 | The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture Page 4 | President Thabo Mbeki Page 18 | Wangari Maathai Page 26 | Archbishop Desmond Tutu Page 34 | President William J. Clinton The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture | PAGE 1 PAGE 2 | The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture 2007 PAGE 2 | The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture he Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF), The inaugural Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture was through its Centre of Memory and held on 19 July 2003, and was delivered by T Dialogue, seeks to contribute to a just President William Jefferson Clinton. The second society by promoting the vision and work of its Founder Annual Lecture was delivered by Nobel Peace Prize and, using his example, to convene dialogue around winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu on 23 November critical social issues. 2004. The third Annual Lecture was delivered on 19 July 2005 by Nobel Peace Prize winner, Professor Our Founder, Nelson Mandela, based his entire life Wangari Maathai MP, from Kenya. The fourth on the principle of dialogue, the art of listening Annual Lecture was delivered by President Thabo and speaking to others; it is also the art of getting Mbeki on 29 July 2006. others to listen and speak to each other. The NMF’s Centre of Memory and Dialogue encourages people Nobel Peace Prize winner, Mr Kofi Annan, the former to enter into dialogue – often about difficult Secretary-General of the United Nations, will deliver the subjects – in order to address the challenges we fifth Annual Lecture on 22 July 2007. face today. The Centre provides the historic resources and a safe, non-partisan space, physically and intellectually, where open and frank This booklet consolidates the four Annual Lectures discourse can take place. -

The Foreign Policies of Mandela and Mbeki: a Clear Case of Idealism Vs Realism ?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository THE FOREIGN POLICIES OF MANDELA AND MBEKI: A CLEAR CASE OF IDEALISM VS REALISM ? by CHRISTIAN YOULA Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Studies) at Stellenbosch University Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Dr Karen Smith March 2009 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 28 February 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Abstract After 1994, South African foreign policymakers faced the challenge of reintegrating a country, isolated for many years as a result of the previous government’s apartheid policies, into the international system. In the process of transforming South Africa's foreign identity from a pariah state to a respected international player, some commentators contend that presidents Mandela and Mbeki were informed by two contrasting theories of International Relations (IR), namely, idealism and realism, respectively. In light of the above-stated popular assumptions and interpretations of the foreign policies of Presidents Mandela and Mbeki, this study is motivated by the primary aim to investigate the classification of their foreign policy within the broader framework of IR theory. This is done by sketching a brief overview of the IR theories of idealism, realism and constructivism, followed by an analysis of the foreign policies of these two statesmen in order to identify some of the principles that underpin them. -

South Africa Tackles Global Apartheid: Is the Reform Strategy Working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, Pp.819-841

critical essays on South African sub-imperialism regional dominance and global deputy-sheriff duty in the run-up to the March 2013 BRICS summit by Patrick Bond Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africas Development – in Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnstone (Eds), Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, London, Pluto Press, 2005, pp.230-236. US empire and South African subimperialism - in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys (Eds), Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded, London, Merlin Press, 2004, pp.125- 144. Talk left, walk right: Rhetoric and reality in the New South Africa – Global Dialogue, 2004, 6, 4, pp.127-140. Bankrupt Africa: Imperialism, subimperialism and financial politics - Historical Materialism, 12, 4, 2004, pp.145-172. The ANCs “left turn” and South African subimperialism: Ideology, geopolitics and capital accumulation - Review of African Political Economy, 102, September 2004, pp.595-611. South Africa tackles Global Apartheid: Is the reform strategy working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, pp.819-841. Removing Neocolonialisms APRM Mask: A critique of the African Peer Review Mechanism – Review of African Political Economy, 36, 122, December 2009, pp. 595-603. South African imperial supremacy - Le Monde Diplomatique, Paris, May 2010. South Africas dangerously unsafe financial intercourse - Counterpunch, 24 April 2012. Financialization, corporate power and South African subimperialism - in Ronald W. Cox, ed., Corporate Power in American Foreign Policy, London, Routledge Press, 2012, pp.114-132. Which Africans will Obama whack next? – forthcoming in Monthly Review, January 2012. 2 Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Introduction Distorted forms of capital accumulation and class formation associated with neoliberalism continue to amplify Africa’s crisis of combined and uneven development. -

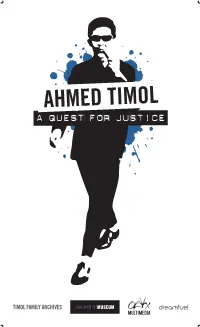

Ahmed Timol Was the First Detainee to Die at John Vorster Square

“He hung from a piece of soap while washing…” In Detention, Chris van Wyk, 1979 On 23 August 1968, Prime Minister Vorster opened a new police station in Johannesburg known as John Vorster Square. Police described it as a state of the art facility, where incidents such as the 1964 “suicide” of political detainee, Suliman “Babla” Saloojee, could be avoided. On 9 September 1964 Saloojee fell or was thrown from the 7th floor of the old Gray’s Building, the Special Branch’s then-headquarters in Johannesburg. Security police routinely tortured political detainees on the 9th and 10th floors of John Vorster Square. Between 1971 and 1990 a number of political detainees died there. Ahmed Timol was the first detainee to die at John Vorster Square. 27 October 1971 – Ahmed Timol 11 December 1976 – Mlungisi Tshazibane 15 February 1977 – Matthews Marwale Mabelane 5 February 1982 – Neil Aggett 8 August 1982 – Ernest Moabi Dipale 30 January 1990 – Clayton Sizwe Sithole 1 Rapport, 31 October 1971 Courtesy of the Timol Family Courtesy of the Timol A FAMILY ON THE MOVE Haji Yusuf Ahmed Timol, Ahmed Timol’s father, was The young Ahmed suffered from bronchitis and born in Kholvad, India, and travelled to South Africa in became a patient of Dr Yusuf Dadoo, who was the 1918. In 1933 he married Hawa Ismail Dindar. chairman of the South African Indian Congress and the South African Communist Party. Ahmed Timol, one of six children, was born in Breyten in the then Transvaal, on 3 November 1941. He and his Dr Dadoo’s broad-mindedness and pursuit of siblings were initially home-schooled because there was non-racialism were to have a major influence on no school for Indian children in Breyten. -

Harmony and Discord in South African Foreign Policy Making

Composers, conductors and players: Harmony and discord in South African foreign policy making TIM HUGHES KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG • OCCASIONAL PAPERS • JOHANNESBURG • SEPTEMBER 2004 © KAS, 2004 All rights reserved While copyright in this publication as a whole is vested in the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung, copyright in the text rests with the individual authors, and no paper may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both authors and the publisher. It should be noted that any opinions expressed are the responsibility of the individual authors and that the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung does not necessarily subscribe to the opinions of contributors. ISBN: 0-620-33027-9 Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 60 Hume Road Dunkeld 2196 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa PO Box 1383 Houghton 2041 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa Telephone: (+27 +11) 214-2900 Telefax: (+27 +11) 214-2913/4 E-mail: [email protected] www.kas.org.za Editing, DTP and production: Tyrus Text and Design Cover design: Heather Botha Reproduction: Rapid Repro Printing: Stups Printing Foreword The process of foreign policy making in South Africa during its decade of democracy has been subject to a complex interplay of competing forces. Policy shifts of the post-apartheid period not only necessitated new visions for the future but also new structures. The creation of a value-based new identity in foreign policy needed to be accompanied by a transformation of institutions relevant for the decision-making process in foreign policy. Looking at foreign policy in the era of President Mbeki, however, it becomes obvious that Max Weber’s observation that “in a modern state the actual ruler is necessarily and unavoidably the bureaucracy, since power is exercised neither through parliamentary speeches nor monarchical enumerations but through the routines of administration”,* no longer holds in the South African context.