Author Accepted Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Racialism, Non-Collaboration and Communism in South Africa

Non-racialism, non-collaboration and Communism in South Africa: The contribution of Yusuf Dadoo during his exile years (1960-1983) Paper presented at the Conference on ‘Yusuf Dadoo, 1909-2009: Marxism, non-racialism and the shaping of the South African liberation struggle’ University of Johannesburg, 4-5 September 2009 Allison Drew Department of Politics University of York, UK It has often been argued by our opponents that Communism was brought to our country by whites and foreigners, that it is an alien importation unacceptable to the indigenous majority. Our reply to this is that the concept of the brotherhood of man, of the sharing of the fruits of the earth, is common to all humanity, black and white, east and west, and has been formulated in one form or another throughout history (Yusuf Dadoo, 1981).1 This paper examines Yusuf Dadoo’s contribution to the thinking and practice of non- racialism during his years in exile. Non-racialism refers to the rejection of racial ideology − the belief that human beings belong to different races. Instead, it stresses the idea of one human race. Organizationally, it implies the recruitment of individual members without regards to colour, ethnic or racial criteria. Non-racialism has long been a subject of debate on the South African left as socialists struggled with the problems of how to organize political movements in a manner that did not reinforce state-imposed racial and ethnic divisions and promote non-racialism in conditions of extremes racial inequality. The South African Communist Party (SACP) was formed in 1953 as a clandestine body that prioritized alliance politics over the development of an independent profile. -

Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo

YUSUF MOHAMED DADOO SOUTH AFRICA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE Statements, Speeches and Articles including Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi Compiled and edited by E. S. Reddy With a foreword by Shri R. Venkataraman President of India Namedia Foundation STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED New Delhi, 1990 [NOTE: A revised and expanded edition of this book was published in South Africa in 1991 jointly by Madiba Publishers, Durban, and UWC Historical and Cultural Centre, Bellville. The South African edition was edited by Prof. Fatima Meer. The present version includes items additional to that in the two printed editions.] FOREWORD TO THE INDIAN EDITION The South African struggle against apartheid occupies a cherished place in our hearts. This is not just because the Father of our Nation commenced his political career in South Africa and forged the instrument of Satyagraha in that country but because successive generations of Indians settled in South Africa have continued the resistance to racial oppression. Hailing from different parts of the Indian sub- continent and professing the different faiths of India, they have offered consistent solidarity and participation in the heroic fight of the people of South Africa for liberation. Among these brave Indians, the name of Dr. Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo is specially remembered for his remarkable achievements in bringing together the Indian community of South Africa with the African majority, in the latter's struggle against racism. Dr. Dadoo met Gandhiji in India and was in correspondence with him during a decisive phase of the struggle in South Africa. And Dr. Dadoo later became an esteemed colleague of the outstanding South African leader, Nelson Mandela. -

Mayor of Joburg, India's Republic Day Celebration

SPEECH BY CLR MPHO PARKS TAU, EXECUTIVE MAYOR OF JOHANNESBURG, INDIA’S REPUBLIC DAY CELEBRATION, HOUGHTON, JOHANNESBURG, 26 JANUARY, 2014 Your Excellency, Honourable High Commissioner of India, Ms. Ruchi Ghanashyam Consul General Mr. Randhir Jaiswal High Commissioners, Ambassadors, and other Members of the Diplomatic Corps, Officials from the City of Johannesburg Ladies and gentlemen Good Evening As the Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg I would like to thank the Indian government, through you, your Excellency the High Commissioner of India, Ms. Ruchi Ghanashyam, for inviting us to this important function, commemorating the day in which the Constitution of India came into force on 26 January 1950. This is an important day in India’s political calendar. On this day, the people of India finally freed themselves from the clutches of colonialism, following independence in 1947. As South Africans we identify with your struggle for freedom and draw our own parallels with the course of events in India. For us, your 26 January is the symbolic equivalent of our April 27, the day on which we liberated ourselves from neo- colonialism, following almost 300 years of racial oppression. The day is also equivalent to May 28, 1996 when as South Africa we adopted what 1 came to be known as the most liberal constitution in the world. Indian independence was undoubtedly one of the most crucial events in the past several generations: world-wide, there were many struggles against imperialism thereafter, but with India a free nation, the writing was on the wall for empire in the post-war world. -

Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’S Religio-Political Thought

ISLAMIC LIBERATION THEOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA: FARID ESACK’S RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHT Yusuf Enes Sezgin A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Cemil Aydin Susan Dabney Pennybacker Juliane Hammer ã2020 Yusuf Enes Sezgin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Yusuf Enes Sezgin: Islamic Liberation Theology in South Africa: Farid Esack’s Religio-Political Thought (Under the direction of Cemil Aydin) In this thesis, through analyzing the religiopolitical ideas of Farid Esack, I explore the local and global historical factors that made possible the emergence of Islamic liberation theology in South Africa. The study reveals how Esack defined and improved Islamic liberation theology in the South African context, how he converged with and diverged from the mainstream transnational Muslim political thought of the time, and how he engaged with Christian liberation theology. I argue that locating Islamic liberation theology within the debate on transnational Islamism of the 1970s onwards helps to explore the often-overlooked internal diversity of contemporary Muslim political thought. Moreover, it might provide important insights into the possible continuities between the emancipatory Muslim thought of the pre-1980s and Islamic liberation theology. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to many wonderful people who have helped me to move forward on my academic journey and provided generous support along the way. I would like to thank my teachers at Boğaziçi University from whom I learned so much. I was very lucky to take two great courses from Zeynep Kadirbeyoğlu whose classrooms and mentorship profoundly improved my research skills and made possible to discover my interests at an early stage. -

The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture

The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture Contents Page 3 | The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture Page 4 | President Thabo Mbeki Page 18 | Wangari Maathai Page 26 | Archbishop Desmond Tutu Page 34 | President William J. Clinton The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture | PAGE 1 PAGE 2 | The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture 2007 PAGE 2 | The Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture he Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF), The inaugural Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture was through its Centre of Memory and held on 19 July 2003, and was delivered by T Dialogue, seeks to contribute to a just President William Jefferson Clinton. The second society by promoting the vision and work of its Founder Annual Lecture was delivered by Nobel Peace Prize and, using his example, to convene dialogue around winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu on 23 November critical social issues. 2004. The third Annual Lecture was delivered on 19 July 2005 by Nobel Peace Prize winner, Professor Our Founder, Nelson Mandela, based his entire life Wangari Maathai MP, from Kenya. The fourth on the principle of dialogue, the art of listening Annual Lecture was delivered by President Thabo and speaking to others; it is also the art of getting Mbeki on 29 July 2006. others to listen and speak to each other. The NMF’s Centre of Memory and Dialogue encourages people Nobel Peace Prize winner, Mr Kofi Annan, the former to enter into dialogue – often about difficult Secretary-General of the United Nations, will deliver the subjects – in order to address the challenges we fifth Annual Lecture on 22 July 2007. face today. The Centre provides the historic resources and a safe, non-partisan space, physically and intellectually, where open and frank This booklet consolidates the four Annual Lectures discourse can take place. -

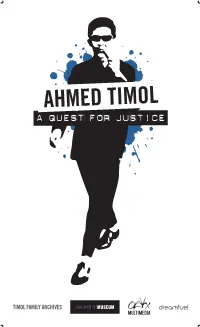

Ahmed Timol Was the First Detainee to Die at John Vorster Square

“He hung from a piece of soap while washing…” In Detention, Chris van Wyk, 1979 On 23 August 1968, Prime Minister Vorster opened a new police station in Johannesburg known as John Vorster Square. Police described it as a state of the art facility, where incidents such as the 1964 “suicide” of political detainee, Suliman “Babla” Saloojee, could be avoided. On 9 September 1964 Saloojee fell or was thrown from the 7th floor of the old Gray’s Building, the Special Branch’s then-headquarters in Johannesburg. Security police routinely tortured political detainees on the 9th and 10th floors of John Vorster Square. Between 1971 and 1990 a number of political detainees died there. Ahmed Timol was the first detainee to die at John Vorster Square. 27 October 1971 – Ahmed Timol 11 December 1976 – Mlungisi Tshazibane 15 February 1977 – Matthews Marwale Mabelane 5 February 1982 – Neil Aggett 8 August 1982 – Ernest Moabi Dipale 30 January 1990 – Clayton Sizwe Sithole 1 Rapport, 31 October 1971 Courtesy of the Timol Family Courtesy of the Timol A FAMILY ON THE MOVE Haji Yusuf Ahmed Timol, Ahmed Timol’s father, was The young Ahmed suffered from bronchitis and born in Kholvad, India, and travelled to South Africa in became a patient of Dr Yusuf Dadoo, who was the 1918. In 1933 he married Hawa Ismail Dindar. chairman of the South African Indian Congress and the South African Communist Party. Ahmed Timol, one of six children, was born in Breyten in the then Transvaal, on 3 November 1941. He and his Dr Dadoo’s broad-mindedness and pursuit of siblings were initially home-schooled because there was non-racialism were to have a major influence on no school for Indian children in Breyten. -

African National African National Congress

AFRICAN NATIONAL AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS STATEMENT ON THE DEATH OF YUSUF DADOO IsitwalandweSeankoe A MESSAGE OF THE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE AT THE FUNERAL OF COMRADE YUSUF DADOO BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS We are gathered here to pay homage to an outstanding leader of the African liberatory struggle, a comrade and friend who devoted most of his life in the service of his people; a communist of world prominence; a dedicated and convinced internationalist who has played an effective role in the anti-imperialist movement for world peace and security and for the social progress of mankind. Loved and adnired throughout our Movement, 'Doc' - as he was popularly known - combined the best qualities of a revolutionary patriot and dynamic leader of the working class. Because of his clear understanding of the factors underlying national oppression and economic exploitation of the black South African masses. he was able, in his own unassuming manner, to guide and inspire others to commit themselves fully in the struggle for the noble ideals of freedom, democracy and a just social order. Most important of all, he led by example. Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo was a first-born in a relatively well-to-do family. But material wealth had no attraction for him. He studied medicine qualifying in Edinburgh University in 1936. On his return to South Africa, he started his medical practice amidst the poverty-stricken and starving victims of racial oppression ad class exploitation. The focus of his pre-occupation soon shifted from healing the sick to working for the abolition of the system by which an entire people suffered at the hands of a few. -

No Bread for Mandela: Memoirs of Ahmed Kathrada, Prisoner No. 468/64'

H-SAfrica Burton on Kathrada, 'No Bread for Mandela: Memoirs of Ahmed Kathrada, Prisoner No. 468/64' Review published on Tuesday, May 29, 2012 A. M. Kathrada. No Bread for Mandela: Memoirs of Ahmed Kathrada, Prisoner No. 468/64. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2011. xxiii + 400 pp. Illustrations. $19.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8131-3375-1. Reviewed by Antoinette Burton (University of Illinois)Published on H-SAfrica (May, 2012) Commissioned by Alex Lichtenstein In a recent issue of South Africa’sSunday Tribune, the journalist Dennis Pather recounted an anecdote about President Jacob Zuma that was designed to underscore how far Zuma has traveled since his radical political days.[1] It was 1974, and Zuma was struggling to make ends meet during the first days and weeks after his release from Robben Island. Subject to the notorious dompass laws- -by which he could be “endorsed out” of Durban in a heartbeat--he found a job as a birdseed packer in Berea Road for a meager wage. Frustrated by the terrible work and the terrible pay, he decided to get a driver’s license so he would have better employment options. The white inspector summarily failed him because he was unable to control his vehicle as it raced down the back side of the notoriously steep Sydenham Hill. Fearful that his chances for a license had slipped away, Zuma asked the inspector: “Sir, does your hand reach your mouth?”--by which he meant, the work I do earns me so little I can’t feed myself. To make a long story short, Zuma was granted his license, and the rest is history. -

ANNUAL REPORT I. Nineteen-Sixty Was a Year of Tremendous

AMERICAN COMMITTEE ON AFRICA ANNUAL REPORT I. Nineteen-sixty was a year of tremendous importance for Africa. Even as late as the 1a tter part of 1959 it was prophesied that only four states would become independent during 1960. Before 1960 there were nine independent countries {excluding the Union of South Africa) and it seemed that the year 1960 would end t~ith only 12 independent states on the continent. Actually 17 · new cout..tries were born in "Africa 1 s Year 11 , and the nations in the African bloc .in the United Nations rose to twent,r-five in number, Mauritania having become independent, but not yet voted into the United Nations. Thus African countries became the largest single group of nations in the United Nations. Both because of the number of African states in the United Nations and because of the urgency of developments on the African continent, the Fifteenth Session of the United Nations General Assembly was almost dominated by issues relating to Africa and colonialism. First, and of most importe.nce, was the crisis that developed in the Congo following independence on June 30th~ The pc1-rer vacuum which developed in the Congo because. of the lack of unity among the African leaders there, because of the divisions which existed among the African states, and beacuse of the relative ineffectiveness of the United Nations to fill the vacuum, for the first time permit ted the cold war to enter Africa in a significant way. Secondly, the killing of 72 1.mar~d Africans in the town of Sharpeville in South Africa by armed troops and soldiers brought the South African trageqy forcefully to the attention of the world and added urgency to the debates on apartheid at the United Nations. -

The Alliance of the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party

Page 38 Oshkosh Scholar Reds and Patriots: The Alliance of the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party Christopher Gauger, author Dr. Michael Rutz, History, faculty mentor Christopher Gauger graduated from UW Oshkosh in spring 2017 with a bachelor of science degree in history and a minor in geography. He also conducted research and public history work for an internship with the Oshkosh World War I Commemoration Committee. His primary historical interests include the Cold War and military history from 1900 to the present. This article originated as a research paper for a seminar on apartheid in South Africa and evolved into a historiographical paper. Christopher is interested in continuing his studies through graduate school, with an eye toward a career in public history and writing literature about historical subjects. Professor Michael Rutz graduated from the University of Michigan in 1992 and received an M.A. and Ph.D. in history from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, in 2002. Dr. Rutz has taught courses on modern world history, British and European history, and African history at UW Oshkosh for 15 years. He is the author of The British Zion: Congregationalism, Politics, and Empire 1790–1850, and several articles on the history of religion and politics in the British Empire. His second book, King Leopold’s Congo and the “Scramble for Africa”: A Short History with Documents, was published in early 2018. Abstract During the apartheid era in South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) was allied with the South African Communist Party (SACP), presenting a united opposition to the white minority government. -

Gandhi, Mandela, and the African Modern

Gandhi, Mandela, and the African Modern Jonathan Hyslop APRIL 2008, PAPER NUMBER 33 © 2008 Unpublished by Jonathan Hyslop The Occasional Papers of the School of Social Science are versions of talks given at the School’s weekly Thursday Seminar. At these seminars, Members present work-in-progress and then take questions. There is often lively conversation and debate, some of which will be included with the papers. We have chosen papers we thought would be of interest to a broad audience. Our aim is to capture some part of the cross-disciplinary conversations that are the mark of the School’s programs. While Members are drawn from specific disciplines of the social sciences— anthropology, economics, sociology and political science—as well as history, philosophy, literature and law, the School encourages new approaches that arise from exposure to different forms of interpretation. The papers in this series differ widely in their topics, methods, and disciplines. Yet they concur in a broadly humanistic attempt to understand how, and under what conditions, the concepts that order experience in different cultures and societies are produced, and how they change. Jonathan Hyslop is Professor of Sociology and History at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, where he is also Deputy Director of the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research. He has been a member of the IAS for 2007-2008. Jonathan Hyslop has published widely on southern African social history. He is currently working on a book about military cultures in 20th century South Africa. Forthcoming in Achille Mbembe and Sarah Nuttall, eds. Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008). -

Southernnumber I Af RICA $1.25 January 1980

Volume Xlll SOUTHERNNumber I Af RICA $1.25 January 1980 Tanzania 8shs. Mozambique 35esc. BECOME A SUSTAINER OF SOUTHERN AFRICA MAGAZINE and receive a speciai gift of your choice The US State Department is a Southern readers had already found that out in 1975. Africa subscriber, but that rarely seems to af The magazine has been bringing you reliable fect department thinking on southern Africa. news, analysis and exclusive reports for many October 1979 news of a secret State Depart years now. But our kind of journalism does not ment report on Cuba-Angola links made us lend itself to huge corporate grants-we've wonder whether officials might have started been too busy exposing corporate involvement reading their copies to help sort out their posi in South Africa, for instance. And so the tion on Africa. The report conceded that Fidel magazine depends heavily on the support of its Castro was no Soviet puppet, and had not readers. As costs rise it is becoming increas been under Soviet orders when he sent Cuban ingly difficult to keep publishing. Help ensure troops to help Angola drive out South African the future of Southern Africa by becoming a invaders in the first months of independence. sustainer for $30 or $50 per year, and we will But the State Department must have been us send you a gift, as well as your copies of the ing back issues of Southern Africa. Our magazine. Become a sustainer for $50.00 per year and you will receive a year's subscription to Southern Africa plus a choice of one of two important new Monthly Review Press books just published in hardback.