The Next Chapter: President Obama's Second-Term Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Russia Trying to Defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Russian Journal of Economics 2 (2016) 146–161 www.rujec.org What is Russia trying to defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev Institute for Industrial and Market Studies, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia Abstract Contrary to the focus on the events of the last two years (2014–2015) associated with the accession of Crimea to Russia and military conflict in Eastern Ukraine, in this study, I stress that serious changes in Russian domestic policy (with strong pres sure on political opposition, state propaganda and sharp anti-Western rhetoric, as well as the fight against “foreign agents’) became visible in 2012. Geopolitical ambitions to revise the “global order” (introduced by the USA after the collapse of the USSR) and the increased role of Russia in “global governance” were declared by leaders of the country much earlier, with Vladimir Putin’s famous Munich speech in 2007. These ambitions were based on the robust economic growth of the mid-2000s, which en couraged the Russian ruling elite to adopt the view that Russia (with its huge energy resources) is a new economic superpower. In this paper, I will show that the con cept of “Militant Russia” in a proper sense can be attributed rather to the period of the mid-2000s. After 2008–2009, the global financial crisis and, especially, the Arab Spring and mass political protests against electoral fraud in Moscow in December 2011, the Russian ruling elite made mostly “militant” attempts to defend its power and assets. © 2016 Non-profit partnership “Voprosy Ekonomiki”. Hosting by Elsevier B.V. -

Hull Fa1nilies United States

Hull Fa1nilies • lll The United States By REV. WILLIAM E. HULL Copyright 1964 by WILLIAM E. HULL Printed by WOODBURN PRINTING CO - INC. Terre Haute, Indiana CONTENTS PAGE Appreciation ii Introduction ......................... ......... .................................... ...................... iii The Hon. Cordell Hull.......................................................................... 1 Hull Family of Yorkshire, England .................................................. 2 Hull Families of Somersetshire, England ........................................ 54 Hull Families of London, England ........... ........................................ 75 Richard Anderson Hull of New Jer;;ey .......................................... 81 Hull Families of Ireland ...................................................................... 87 Hull-Trowell Lines of Florida ............................................................ 91 William Hu:l Line of Kansas .............................................................. 94 James Hull Family of New Jersey.................................................... 95 William Hull Family of New Foundland ........................................ 97 Hulls Who Have Attained Prominence ............................................ 97 Rev. Wm. E. Hull Myrtle Altus Hull APPRECIATION The writing of this History of the Hull Families in the United States has been a labor of love, moved, we feel, by a justifiable pride in the several family lines whose influence has been a source of strength wherever families bearing -

The Situation of Minority Children in Russia

The Situation of Children Belonging to Vulnerable Groups in Russia Alternative Report March 2013 Anti- Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL” The NGO, Anti-Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL”, was registered in 2007 and continued work on a number of human rights and anti-discrimination projects previously coordinated by the Charitable Educational Human Rights NGO “MEMORIAL” of St. Petersburg. ADC “Memorial‟s mission is to defend the rights of individuals subject to or at risk of discrimination by providing a proactive response to human rights violations, including legal assistance, human rights education, research, and publications. ADC Memorial‟s strategic goals are the total eradication of discrimination at state level; the adoption of anti- discrimination legislation in Russia; overcoming all forms of racism and nationalism; Human Rights education; and building tolerance among the Russian people. ADC Memorial‟s vision is the recognition of non-discrimination as a precondition for the realization of all the rights of each person. Tel: +7 (812) 317-89-30 E-mail: [email protected] Contributors The report has been prepared by Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” with editorial direction of Stephania Kulaeva and Olga Abramenko. Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” would like to thank Simon Papuashvili of International Partnership for Human Rights for his assistance in putting this report together and Ksenia Orlova of ADC “Memorial” for allowing us to use the picture for the cover page. Page 2 of 47 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 7 Overview of the legal and policy initiatives implemented in the reporting period ................. 11 Violations of the rights of children involving law enforcement agencies ............................... -

Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests

Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol, Coordinator Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs March 5, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33407 Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests Summary Russia made uneven progress in democratization during the 1990s, but this limited progress was reversed after Vladimir Putin rose to power in 1999-2000, according to many observers. During this period, the State Duma (lower legislative chamber) became dominated by government- approved parties, gubernatorial elections were abolished, and the government consolidated ownership or control over major media and industries, including the energy sector. The Putin government showed low regard for the rule of law and human rights in suppressing insurgency in the North Caucasus, according to critics. Dmitry Medvedev, Putin’s longtime protégé, was elected president in 2008; President Medvedev immediately designated Putin as prime minister and continued Putin’s policies. In August 2008, the Medvedev-Putin “tandem” directed military operations against Georgia and recognized the independence of Georgia’s separatist South Ossetia and Abkhazia, actions condemned by most of the international community. In late 2011, Putin announced that he would return to the presidency and Medvedev would become prime minister. This announcement, and flawed Duma elections at the end of the year, spurred popular protests, which the government addressed by launching a few reforms and holding pro-Putin rallies. In March 2012, Putin was (re)elected president by a wide margin. The day after Putin’s inauguration in May 2012, the legislature confirmed Medvedev as prime minister. -

Final Catalogue

Price Sub Price Qty. Seq. ISBN13 Title Author Category Year After Category USD Needed 70% 1 9780387257099 Accounting and Financial System Robert W. McGee, Barry University, Miami Shores, FL, USA; Galina Accounting Auditing 2006 125 38 Reform in Eastern Europe and Asia G. Preobragenskaya, Omsk State University, Omsk, Russia 2 9783540308010 Regulatory Risk and the Cost of Capital Burkhard Pedell, University of Stuttgart, Germany Accounting Auditing 2006 115 35 3 9780387265971 Economics of Accounting Peter Ove Christensen, University of Aarhus, Aarhus C, Denmark; Accounting Auditing 2005 149 45 Gerald Feltham, The University of British Columbia, Faculty of Commerce & Business Administration 4 9780387238470 Accounting and Financial System Robert W. McGee, Barry University, Miami Shores, FL, USA; Galina Accounting Auditing 2005 139 42 Reform in a Transition Economy: A G. Preobragenskaya, Omsk State University, Omsk, Russia Case Study of Russia 5 9783540408208 Business Intelligence Techniques Murugan Anandarajan, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Accounting Auditing 2004 145 44 Asokan Anandarajan, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ, USA; Cadambi A. Srinivasan, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA (Eds.) 6 9780387239323 Economics of Accounting Peter O. Christensen, University of Southern Denmark-Odense, Accounting Special 2003 85 25 Denmark; G.A. Feltham, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Topics BC, Canada 7 9781402072291 Economics of Accounting Peter O Christensen, University of Southern Denmark-Odense, Accounting Auditing 2002 185 56 Denmark; G.A. Feltham, Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada 8 9780792376491 The Audit Committee: Performing Laura F. Spira Accounting Special 2002 175 53 Corporate Governance Topics 9 9781846280207 Adobe® Acrobat® and PDF for Tom Carson, New Economy Institute, Chattanooga, TN 37403, USA.; Architecture Design, 2006 85 25 Architecture, Engineering, and Donna L. -

Russia's Ban on Adoptions by US Citizens

\\jciprod01\productn\M\MAT\28-1\MAT110.txt unknown Seq: 1 16-OCT-15 15:11 Vol. 28, 2015 Russia’s Ban on Adoptions by U.S. Citizens 51 The New Cold War: Russia’s Ban on Adoptions by U.S. Citizens by Cynthia Hawkins DeBose* and Ekaterina DeAngelo** Table of Contents I. Introduction ....................................... 52 R II. Historical Background of American and Russian Intercountry Adoption ............................. 54 R A. Development of Intercountry Adoption in the United States .................................. 54 R B. Development of Intercountry Adoption Between Russia and the United States ........ 56 R III. Russian Intercountry Adoption Laws .............. 58 R A. Laws Governing Intercountry Adoptions in Russia ......................................... 58 R B. Recent Changes to the Laws Governing American Adoptions of Russian Orphans ..... 61 R 1. The United States–Russia Adoption Agreement................................. 61 R 2. The Russian Law Banning American Adoptions and Controversy over the Ban . 63 R a. The American Adoption Ban and Its Effect on Intercountry Adoption of Russian Orphans ...................... 63 R b. Arguments in Support of and in Opposition to the American Adoption Ban in Russia .......................... 65 R * Professor of Law, Stetson University College of Law (SUCOL). B.A. Wellesley College; J.D. Harvard Law School. Thank you to Alicia Tarrant (SUCOL, 2016) for her invaluable research assistance and Roman Faizorin (SUCOL, 2018) for his Russian to English translation of Russian source materi- als. This project was supported by a SUCOL Faculty Research Grant. ** Assistant Attorney General of Texas, Environmental Protection Divi- sion. Ufa Law Institute of the Interior Ministry of Russian Federation, 2007; J.D. Stetson University College of Law, 2013. -

Russia 2019 Human Rights Report

RUSSIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Russian Federation has a highly centralized, authoritarian political system dominated by President Vladimir Putin. The bicameral Federal Assembly consists of a directly elected lower house (State Duma) and an appointed upper house (Federation Council), both of which lack independence from the executive. The 2016 State Duma elections and the 2018 presidential election were marked by accusations of government interference and manipulation of the electoral process, including the exclusion of meaningful opposition candidates. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Investigative Committee, the Office of the Prosecutor General, and the National Guard are responsible for law enforcement. The FSB is responsible for state security, counterintelligence, and counterterrorism as well as for fighting organized crime and corruption. The national police force, under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, is responsible for combating all crime. The National Guard assists the FSB Border Guard Service in securing borders, administers gun control, combats terrorism and organized crime, protects public order, and guards important state facilities. The National Guard also participates in armed defense of the country’s territory in coordination with Ministry of Defense forces. Except in rare cases, security forces generally reported to civilian authorities. National-level civilian authorities, however, had, at best, limited control over security forces in the Republic of Chechnya, which were accountable only to the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov. The country’s occupation and purported annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula continued to affect the human rights situation there significantly and negatively. The Russian government continued to arm, train, lead, and fight alongside Russia-led forces in eastern Ukraine. -

6–30–10 Vol. 75 No. 125 Wednesday June 30, 2010 Pages 37707–37974

6–30–10 Wednesday Vol. 75 No. 125 June 30, 2010 Pages 37707–37974 VerDate Mar 15 2010 20:04 Jun 29, 2010 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\30JNWS.LOC 30JNWS emcdonald on DSK2BSOYB1PROD with NOTICES6 II Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 125 / Wednesday, June 30, 2010 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

The Russian Adoption Ban Fits the Putin Agenda: the Logic of the Dima

January 2013 1/2013 Sean Roberts Researcher The Finnish Institute of International Affairs The Russian adoption ban fits the Putin agenda > The logic of the Dima Yakovlev law is inevitable but short-sighted By banning US citizens from adopting Russian orphans, the Putin administration is attempting to deflect attention away from corruption issues and utilise anti- American sentiment to discredit opponents. But these latest efforts at manipulating public opinion may have unintended consequences. In order to make sense of the seem- by the Levada Center in December anti-American sentiment and allows ingly inexplicable adoption ban 2012 showed that just over 20% of an easy association between the that came into force on January 1 respondents opposed the Magnitsky perceived mistreatment of orphans (the so-called ‘Dima Yakovlev law’, Act, but that almost 45% supported in the US and the regime’s domestic named in memory of a Russian US efforts to punish corrupt Russian opponents. orphan who died in 2008 due to the officials. Vladimir Zhirinovksy’s inter- neglect of his US adoptive father), The Dima Yakovlev law is a useful view on the Vesti news channel on it is important to look beyond the way to deflect attention away from December 24 is a typical example. format of Russia-US relations and to the entire issue of corruption at a After singling out the US for its consider the current configuration of time when this should be in the treatment of Russian orphans, he politics within Russia, as well as the public eye. Putin’s firing of Defence moved seamlessly to attack the US- core issue at stake. -

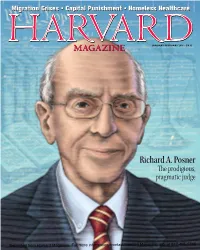

Richard A. Posner the Prodigious, Pragmatic Judge

Migration Crises • Capital Punishment • Homeless Healthcare january-february 2016 • $4.95 Richard A. Posner The prodigious, pragmatic judge Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 OnlyOnlyOnly onon on KiawahKiawah Kiawah Island.Island. Island. THETHETHE OCEANOCEAN OCEAN COURSECOURSE COURSE CASSIQUECASSIQUECASSIQUE ANDAND AND RIVERRIVERRIVER COURSECOURSE COURSE ANDAND AND BEACHBEACHBEACH CLUBCLUB CLUB SANCTUARYSANCTUARYSANCTUARY HOTELHOTEL HOTEL OCEANOCEANOCEAN PARKPARK PARK 201220122012 PGAPGA PGA CHAMPIONSHIPCHAMPIONSHIP CHAMPIONSHIP SPORTSSPORTSSPORTS PAVILIONPAVILION PAVILION FRESHFIELDSFRESHFIELDSFRESHFIELDS VILLAGEVILLAGE VILLAGE SASANQUASASANQUASASANQUA SPASPA SPA HISTORICHISTORICHISTORIC CHARLESTONCHARLESTON CHARLESTON KiawahKiawahKiawah IslandIsland Island hashas has beenbeen been namednamed named CondéCondé Condé NastNast Nast Traveler’sTraveler’s Traveler’s #1#1 #1 islandisland island inin in thethe the USAUSA USA (and(and (and #2#2 #2 inin in thethe the world)world) world) forforfor aa myriadmyriada myriad ofof of reasonsreasons reasons –– 10–10 10 milesmiles miles ofof of uncrowdeduncrowded uncrowded beach,beach, beach, iconiciconic iconic golfgolf golf andand and resort,resort, resort, thethe the allureallure allure ofof of nearbynearby nearby Charleston,Charleston, Charleston, KiawahIsland.comKiawahIsland.comKiawahIsland.com || 866.312.1791 866.312.1791| 866.312.1791 || 1 1| KiawahKiawah1 Kiawah IslandIsland Island ParkwayParkway Parkway || Kiawah Kiawah| Kiawah -

Human Rights in Russia: the Impact of Economic Sanctions And

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL HUMAN RIGHTS IN RUSSIA: THE IMPACT OF ECONOMIC SANCTIONS AND GLOBALIZATION Kathryn Loden Howards Lehman, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Abstract The Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 was designed as a means of punishing individuals and entities who violate human rights, participate in systematic corruption, and fail to uphold the rule of law in Russia. In theory, the Magnitsky Act should improve human rights yet in practice, the economic sanctions and travel bans imposed by the act have done nothing of the sort. Human rights, systematic corruption, and the relationship between the U.S. and Russia have not improved in the years since the implementation of the Magnitsky Act. Instead, all three of these phenomena have declined to unacceptable levels. While it may be too hasty to imply direct causation between the Magnitsky Act of 2012 and the troubling Russo- American relationship that exists today, it is more than fair to suggest that the act has served as one of the dominoes in the line leading to today’s volatile international conflict. The overarching phenomenon that has led to both the Magnitsky Act and the deteriorating Russo-American relationship is globalization; a process that has favored the spread of Western practices and ideologies at the cost of those more traditional to Eastern nations. Analyzing the Russo- American relationship from the context of globalization helps to explain why U.S. efforts have been unsuccessful in improving human rights conditions in Russia. Keywords: Human rights, Russia, United States, Globalization, Economic sanctions ii Table of Contents ABSTRACT ii BACKGROUND 1 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 3 GLOBALIZATION 4 EFFECTIVENESS OF SANCTIONS 7 POLITICAL IMPACT 15 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 21 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORTS 25 a. -

Spring 2011 Newsletter

Spring 2011 Newsletter USJLP Delegates Join Disaster A special message from Relief Efforts in Iwate Prefecture George Packard I want to send deepest condolences to all who have been affected by the events of March 11 and afterwards. It has been a time of terrible tragedy for our Japanese friends and deep concern on the part of millions of Americans who have been touched by these events. Our US-Japan Leadership network of Fellows, delegates and friends has generated a torrent of messages of concern and an extraordinary outpouring of sympathy and offers to help. If there is any silver lining to be found in all this, it is the reaffirmation of the value of our program, where Japanese and Americans have learned to communicate and share their deepest feelings with each other. We are determined to go forward, and we Laura Winthrop (11,12) surveys the devastation in Ofunato, Iwate. believe this summer's conference in Kyoto, She and Spencer Abbot (10,11) share their experiences working with the U.S. government and with volunteer NGOs to assist Japan Hiroshima and elsewhere will be more in this unprecedented time of need. (Story on page 2) important and meaningful than ever before. You will meet in this newsletter the delegates An Outpouring of Support from the for 2011 - arguably one of the strongest classes ever - and I am pleased to note that fully one USJLP Community half of the new faces on each side are women! Within an hour after news of the Tohoku earthquake hit the On behalf of our foundation's board, I send world, USJLPers were online sending messages of concern, warmest congratulations to all the Fellows support, and information over who have blazed the trail to this point.