Assessing Russiaâ•Žs Ban on U.S. Adoptions from a Constructivist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Child Laundering: How the Intercountry Adoption System Legitimizes and Incentivizes the Practices of Buying, Trafficking, Kidnaping, and Stealing Children

CHILD LAUNDERING: HOW THE INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION SYSTEM LEGITIMIZES AND INCENTIVIZES THE PRACTICES OF BUYING, TRAFFICKING, KIDNAPING, AND STEALING CHILDREN DAVID M. SMOLIN† Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ...................................... 115 II. THE INCIDENCE OF CHILD BUYING, STEALING, KIDNAPING, AND TRAFFICKING WITHIN THE INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION SYSTEM ... 117 A. Methods of Operation ............................. 117 1. Child Buying Scenario I ......................... 118 2. Child Buying Scenario II ........................ 119 3. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario I: Kidnaping Children Placed into Orphanages, Hostels, or Schools for Purposes of Education or Care ................... 119 4. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario II: Obtaining Children Through False Pretenses ........................ 121 5. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Children Scenario III: Lost Children ................................... 121 6. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario IV: Traditional Kidnaping .................................. 122 7. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario V: Intra-Familial Kidnaping .................................. 123 8. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario VI: “Your Money or Your Baby:” Taking Children in Payment of a Debt .... 124 B. Extreme Poverty and Sending Nations .................. 124 C. Cycles of Abuse .................................. 132 D. Stories of Abuse: Tracking Child Laundering Within Various Sending Nations ................................. 135 1. Cambodia ................................... 135 2. India ..................................... -

What Is Russia Trying to Defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Russian Journal of Economics 2 (2016) 146–161 www.rujec.org What is Russia trying to defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev Institute for Industrial and Market Studies, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia Abstract Contrary to the focus on the events of the last two years (2014–2015) associated with the accession of Crimea to Russia and military conflict in Eastern Ukraine, in this study, I stress that serious changes in Russian domestic policy (with strong pres sure on political opposition, state propaganda and sharp anti-Western rhetoric, as well as the fight against “foreign agents’) became visible in 2012. Geopolitical ambitions to revise the “global order” (introduced by the USA after the collapse of the USSR) and the increased role of Russia in “global governance” were declared by leaders of the country much earlier, with Vladimir Putin’s famous Munich speech in 2007. These ambitions were based on the robust economic growth of the mid-2000s, which en couraged the Russian ruling elite to adopt the view that Russia (with its huge energy resources) is a new economic superpower. In this paper, I will show that the con cept of “Militant Russia” in a proper sense can be attributed rather to the period of the mid-2000s. After 2008–2009, the global financial crisis and, especially, the Arab Spring and mass political protests against electoral fraud in Moscow in December 2011, the Russian ruling elite made mostly “militant” attempts to defend its power and assets. © 2016 Non-profit partnership “Voprosy Ekonomiki”. Hosting by Elsevier B.V. -

After WTO Membership: Promoting Human Rights in Russia with the Magnitsky Act Ariel Cohen, Phd, and Bryan Riley

BACKGROUNDER No. 2687 | MAY 14, 2012 After WTO Membership: Promoting Human Rights in Russia with the Magnitsky Act Ariel Cohen, PhD, and Bryan Riley Abstract n a few months, Russia will become Russia’s accession to the World Ia member of the World Trade Talking Points Trade Organization (WTO) will put Organization (WTO). U.S. businesses U.S. companies at a disadvantage will not be able to benefit from the ■■ Because of Russia’s imminent with their global competitors unless concessions Russia made to join the accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), U.S. com- Congress first exempts Russia from WTO unless Congress first repeals panies could be placed at a severe the application of the Jackson–Vanik the Jackson–Vanik Amendment, a disadvantage in Russia due to the Amendment, a tool from the 1970s powerful tool that the U.S. success- continued application of the Jack- designed to promote human rights fully used to promote human rights son–Vanik Amendment. that no longer advances that goal. in Soviet Russia and other countries ■■ The U.S. should grant Russia per- Russia admittedly suffers from weak which restricted emigration dur- manent normal trade relations rule of law and pervasive corruption, ing the Cold War. Failure to repeal status, but only after updating its but Congress should pass new human Jackson–Vanik could place U.S. tools for protecting human rights rights legislation rather than try to companies at a disadvantage while in Russia by replacing the Jack- uphold Jackson–Vanik beyond its companies in other WTO members son–Vanik Amendment with the utility. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

082404 Cover

“A celebration of committed individuals who serve as building blocks in the lives of children” Thursday, September 23, 2004 Washington, DC 2 ach year, the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute, CCAI, invites Members of Congress to recognize those individuals who have made a difference in the lives of orphans and foster children by giving them the Congressional Angels in Adoption™ Award. CCAI is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to raising awareness about the tens of thousands of foster children in this country and the millions of orphans around the world in need of permanent, safe, and loving homes; and to eliminating the barriers that hinder these children from realizing their basic need of a family. 2004 Congressional Awards Celebration Welcome Delilah National Radio Personality Musical Performance Watoto Children’s Choir Kampala, Uganda Message from CCAI President Senator Mary Landrieu Congressional Director, CCAI Message from Founding and Maxine B. Baker Premier Sponsor President and CEO, Freddie Mac Foundation Musical Performance Steven Curtis Chapman Recording Artist/Song Writer Guardian Angel Recognition Kerry Marks Hasenbalg Executive Director, CCAI Invocation Barry Black Chaplain of the United States Senate Recognition of 2004 Angels in Adoption™ Congressional Leadership Dinner Recognition of Congressional Members Delilah Presentation of National Angel in Adoption™ Congressman Jim Oberstar Award to Pat and Ruth Williams Congressional Director, CCAI Presentation of National Angel in Adoption™ Congressman -

Russia's Reaction to the Magnitsky Act and Relations with the West

RUSSIAN ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 120, 23 November 2012 2 Analysis Russia’s Reaction to the Magnitsky Act and Relations With the West Ben Aris, Moscow Abstract The reaction of the US and EU to the death of Sergei Magnitsky by issuing travel bans to 60 Russian offi- cials, and the Magnitsky Act in the US, has become an issue of contention in Russian–Western relations. The Kremlin views the Magnitsky Act as a politically-motivated attempt to interfere in Russian domestic affairs. At the same time, in spite of some mild reforms during the Medvedev Presidency, the Magnitsky case has not had a big impact on either Russian domestic governance or political debate. he death of Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky on Sep- documentaries on YouTube on the “Russian Untouch- Ttember 16, 2009 in a Moscow pre-trial detention ables” and “Hermitage TV” channels). centre was a tragedy and his human rights were almost In November 2008 Magnitsky was arrested on certainly violated. Magnitsky was a Russian national related tax evasion charges, which Browder claims were and a lawyer with the American firm Firestone Dun- instigated as a retaliatory measure by the same officers can. He was representing the UK registered and highly that were involved in the tax rebate scheme. While in successful fund Hermitage Capital, which had fallen prison he fell ill. It later emerged that Magnitsky had foul of the Kremlin. His death became a lightning rod complained of worsening stomach pain for five days prior for tensions between Moscow and Washington and led to his death. Browder and his associates have also found to the passage of the “Justice for Sergei Magnitsky Act” convincing evidence that Magnitsky was beaten while in into the US Congress in 2011, which has driven a wedge jail and died after medical aid, to which he was entitled, between Russia and US foreign relations. -

International Adoption: the Most Logical Solution to the Disparity

INTERNATIONAL ADOPTION: THE MOST LOGICAL SOLUTION TO THE DISPARITY BETWEEN THE NUMBERS OF ORPHANED AND ABANDONED CHILDREN IN SOME COUNTRIES AND FAMILIES AND INDIVIDUALS WISHING TO ADOPT IN OTHERS? Sara R. Wallace* I. INTRODUCTION Throughout the world there are millions of children who lack families, homes, and basic care.1 This problem is especially pronounced in countries where war or national disasters have taken a devastating economic toll on families.2 Many families who cannot afford to provide for their children are left with no choice but to abandon them out of need or shame.3 As a result, many children are left to the streets. For example, up to seven million “meninos da rua” (Portuguese for “children of the street”) live on the streets in Brazil’s large cities.4 Non-economic factors also contribute to children becoming orphans. Social and political circumstances have left children without families. In China, for instance, the One-Child Policy, coupled with Chinese culture’s preference for male children, leads families to abandon or give up for adoption thousands of first-born female children.5 The Korean War left thousands of children in that country homeless.6 Confucian beliefs that emphasize continuance of the family through an unbroken bloodline dissuaded Koreans from adopting children unrelated to them.7 Under the Ceausescu regime in Romania, women were forced * J.D. Candidate, University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law, 2004; Master of Science in Family Studies and Human Development, University of Arizona, 2001; Bachelor of Arts in Psychology, Pepperdine University, 1998. I wish to thank DeAnna Rivera and Rebecca Papoff for their support and thoughtful editing, as well as my friends and family for their continuing encouragement. -

Minority Report: Ukraine As Bugbear

MINORITY REPORT: UKRAINE AS BUGBEAR [NB: Note the byline; I began writing this as one of my Minority Report pieces; it’s been in my Work In Progress folder for nearly two years, and an unfinished draft here at emptywheel for 18 months. I left off work on it well before the final Special Counsel’s Report was published. This post’s content has become more relevant even if it’s not entirely complete, needing more meat in some areas, and now requiring the last two-plus years of fossil fuel-related developments and events related to the U.S.- Ukraine-Russia triangle after the 2016 U.S. general election. /~Rayne] This post looks at the possibility that the hacking of U.S. election system and events affecting the election’s outcome are part of a much larger picture — one in which NATO figures large, and the future of energy figures even larger. One could attribute Russian attempts at hacking and influencing the 2016 general election to retaliation for the CIA’s involvement in Ukraine, or to a personal vendetta against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton with regard to Ukraine ahead of the Maidan revolt, or to rousing anti-Putin sentiment in Russia: … Five years ago, he blamed Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for the anti- Kremlin protests in Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square. “She set the tone for some of our actors in the country and gave the signal,” Putin said. “They heard this and, with the support of the U.S. State Department, began active work.” (No evidence was provided for the accusation.) … But after looking at the mission and history of NATO, the integral role of natural gas to Europe’s industry and continuity, Ukraine’s role as a conduit for Russian gas to European states, one might come to a very different conclusion. -

The Situation of Minority Children in Russia

The Situation of Children Belonging to Vulnerable Groups in Russia Alternative Report March 2013 Anti- Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL” The NGO, Anti-Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL”, was registered in 2007 and continued work on a number of human rights and anti-discrimination projects previously coordinated by the Charitable Educational Human Rights NGO “MEMORIAL” of St. Petersburg. ADC “Memorial‟s mission is to defend the rights of individuals subject to or at risk of discrimination by providing a proactive response to human rights violations, including legal assistance, human rights education, research, and publications. ADC Memorial‟s strategic goals are the total eradication of discrimination at state level; the adoption of anti- discrimination legislation in Russia; overcoming all forms of racism and nationalism; Human Rights education; and building tolerance among the Russian people. ADC Memorial‟s vision is the recognition of non-discrimination as a precondition for the realization of all the rights of each person. Tel: +7 (812) 317-89-30 E-mail: [email protected] Contributors The report has been prepared by Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” with editorial direction of Stephania Kulaeva and Olga Abramenko. Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” would like to thank Simon Papuashvili of International Partnership for Human Rights for his assistance in putting this report together and Ksenia Orlova of ADC “Memorial” for allowing us to use the picture for the cover page. Page 2 of 47 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 7 Overview of the legal and policy initiatives implemented in the reporting period ................. 11 Violations of the rights of children involving law enforcement agencies ............................... -

Russia: Background and U.S

Russia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated August 21, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44775 Russia: Background and U.S. Policy Summary Over the last five years, Congress and the executive branch have closely monitored and responded to new developments in Russian policy. These developments include the following: increasingly authoritarian governance since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidential post in 2012; Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region and support of separatists in eastern Ukraine; violations of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty; Moscow’s intervention in Syria in support of Bashar al Asad’s government; increased military activity in Europe; and cyber-related influence operations that, according to the U.S. intelligence community, have targeted the 2016 U.S. presidential election and countries in Europe. In response, the United States has imposed economic and diplomatic sanctions related to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria, malicious cyber activity, and human rights violations. The United States also has led NATO in developing a new military posture in Central and Eastern Europe designed to reassure allies and deter aggression. U.S. policymakers over the years have identified areas in which U.S. and Russian interests are or could be compatible. The United States and Russia have cooperated successfully on issues such as nuclear arms control and nonproliferation, support for military operations in Afghanistan, the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, the International Space Station, and the removal of chemical weapons from Syria. In addition, the United States and Russia have identified other areas of cooperation, such as countering terrorism, illicit narcotics, and piracy. -

US Sanctions on Russia

U.S. Sanctions on Russia Updated January 17, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45415 SUMMARY R45415 U.S. Sanctions on Russia January 17, 2020 Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavior. The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Cory Welt, Coordinator Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian Specialist in European aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposed sanctions on Russia in Affairs response to (and to deter) election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela. Most Members of Congress support a robust Kristin Archick Specialist in European use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions. Affairs Sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on four executive orders (EOs) that President Obama issued in 2014. That year, Congress also passed and President Rebecca M. Nelson Obama signed into law two acts establishing sanctions in response to Russia’s invasion of Specialist in International Ukraine: the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Trade and Finance Ukraine Act of 2014 (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95/H.R. 4152) and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014 (UFSA; P.L. 113-272/H.R. 5859). Dianne E. Rennack Specialist in Foreign Policy In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the Countering Russian Influence Legislation in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. -

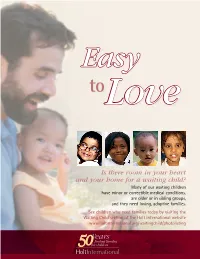

Is There Room in Your Heart and Your Home for a Waiting Child?

Easy toLove Is there room in your heart and your home for a waiting child? Many of our waiting children have minor or correctible medical conditions, are older or in sibling groups, and they need loving, adoptive families. See children who need families today by visiting the Waiting Child section of the Holt International website www.holtinternational.org/waitingchild/photolisting finding families for children Dear Readers Christina* greeted me a few years ago at the home of her foster family in Romania. She was 12 years old, with dark eyes, and dark hair pulled back into a SUMMER 2006 VOL. 48 NO. 3 HOLT INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S SERVICES ponytail that framed her pretty face. I was surprised by how normal and healthy P.O. Box 2880 (1195 City View) Eugene, OR 97402 she looked. Ph: 541/687.2202 Fax: 541/683.6175 OUR MISSION I expected her to look, well… sick. After all, Christina was HIV-positive. Instead I Holt International is dedicated to carrying out God’s plan for every child to have a permanent, loving family. found a girl on the cusp of adolescence who wore the unadorned, fresh beauty of In 1955 Harry and Bertha Holt responded to the conviction that youth. God had called them to help children left homeless by the Korean War. Though it took an act of the U.S. Congress, the Holts adopt- “So this is the face of AIDS,” I marveled. ed eight of those children. But they were moved by the desperate plight of other orphaned children in Korea and other countries In this issue of Holt International magazine, we feature a look at the range of as well, so they founded Holt International Children’s Services in order to unite homeless children with families who would love work Holt is doing around the world for children affected by HIV/AIDS.