Russia's Ban on Adoptions by US Citizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Child Laundering: How the Intercountry Adoption System Legitimizes and Incentivizes the Practices of Buying, Trafficking, Kidnaping, and Stealing Children

CHILD LAUNDERING: HOW THE INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION SYSTEM LEGITIMIZES AND INCENTIVIZES THE PRACTICES OF BUYING, TRAFFICKING, KIDNAPING, AND STEALING CHILDREN DAVID M. SMOLIN† Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ...................................... 115 II. THE INCIDENCE OF CHILD BUYING, STEALING, KIDNAPING, AND TRAFFICKING WITHIN THE INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION SYSTEM ... 117 A. Methods of Operation ............................. 117 1. Child Buying Scenario I ......................... 118 2. Child Buying Scenario II ........................ 119 3. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario I: Kidnaping Children Placed into Orphanages, Hostels, or Schools for Purposes of Education or Care ................... 119 4. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario II: Obtaining Children Through False Pretenses ........................ 121 5. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Children Scenario III: Lost Children ................................... 121 6. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario IV: Traditional Kidnaping .................................. 122 7. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario V: Intra-Familial Kidnaping .................................. 123 8. Child Stealing/Kidnaping Scenario VI: “Your Money or Your Baby:” Taking Children in Payment of a Debt .... 124 B. Extreme Poverty and Sending Nations .................. 124 C. Cycles of Abuse .................................. 132 D. Stories of Abuse: Tracking Child Laundering Within Various Sending Nations ................................. 135 1. Cambodia ................................... 135 2. India ..................................... -

The New Cold War: Russia's Ban on Adoptions by U.S. Citizens

\\jciprod01\productn\M\MAT\28-1\MAT110.txt unknown Seq: 1 16-OCT-15 15:11 Vol. 28, 2015 Russia’s Ban on Adoptions by U.S. Citizens 51 The New Cold War: Russia’s Ban on Adoptions by U.S. Citizens by Cynthia Hawkins DeBose* and Ekaterina DeAngelo** Table of Contents I. Introduction ....................................... 52 R II. Historical Background of American and Russian Intercountry Adoption ............................. 54 R A. Development of Intercountry Adoption in the United States .................................. 54 R B. Development of Intercountry Adoption Between Russia and the United States ........ 56 R III. Russian Intercountry Adoption Laws .............. 58 R A. Laws Governing Intercountry Adoptions in Russia ......................................... 58 R B. Recent Changes to the Laws Governing American Adoptions of Russian Orphans ..... 61 R 1. The United States–Russia Adoption Agreement................................. 61 R 2. The Russian Law Banning American Adoptions and Controversy over the Ban . 63 R a. The American Adoption Ban and Its Effect on Intercountry Adoption of Russian Orphans ...................... 63 R b. Arguments in Support of and in Opposition to the American Adoption Ban in Russia .......................... 65 R * Professor of Law, Stetson University College of Law (SUCOL). B.A. Wellesley College; J.D. Harvard Law School. Thank you to Alicia Tarrant (SUCOL, 2016) for her invaluable research assistance and Roman Faizorin (SUCOL, 2018) for his Russian to English translation of Russian source materi- als. This project was supported by a SUCOL Faculty Research Grant. ** Assistant Attorney General of Texas, Environmental Protection Divi- sion. Ufa Law Institute of the Interior Ministry of Russian Federation, 2007; J.D. Stetson University College of Law, 2013. -

What Is Russia Trying to Defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Russian Journal of Economics 2 (2016) 146–161 www.rujec.org What is Russia trying to defend? ✩ Andrei Yakovlev Institute for Industrial and Market Studies, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia Abstract Contrary to the focus on the events of the last two years (2014–2015) associated with the accession of Crimea to Russia and military conflict in Eastern Ukraine, in this study, I stress that serious changes in Russian domestic policy (with strong pres sure on political opposition, state propaganda and sharp anti-Western rhetoric, as well as the fight against “foreign agents’) became visible in 2012. Geopolitical ambitions to revise the “global order” (introduced by the USA after the collapse of the USSR) and the increased role of Russia in “global governance” were declared by leaders of the country much earlier, with Vladimir Putin’s famous Munich speech in 2007. These ambitions were based on the robust economic growth of the mid-2000s, which en couraged the Russian ruling elite to adopt the view that Russia (with its huge energy resources) is a new economic superpower. In this paper, I will show that the con cept of “Militant Russia” in a proper sense can be attributed rather to the period of the mid-2000s. After 2008–2009, the global financial crisis and, especially, the Arab Spring and mass political protests against electoral fraud in Moscow in December 2011, the Russian ruling elite made mostly “militant” attempts to defend its power and assets. © 2016 Non-profit partnership “Voprosy Ekonomiki”. Hosting by Elsevier B.V. -

A HRC 27 2 AUV Final For

A/HRC/27/2 Advance unedited version Distr.: General 22 December 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-seventh session Agenda item 1 Organizational and procedural matters Report of the Human Rights Council on its twenty-seventh session Vice-President and Rapporteur: Ms. Kateřina Sequensová (Czech Republic) GE.14- A/HRC/27/2 Contents Chapter Paragraphs Page Part One: Resolutions, decisions and President’s statements adopted by the Human Rights Council at its twenty-seventh session ............................................................................................... 4 I. Resolutions ....................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Decisions .......................................................................................................................................... 5 III. President’s statements ...................................................................................................................... 6 Part Two: Summary of proceedings ........................................................................................ 1–1032 7 I. Organizational and procedural matters .................................................................... 1–37 7 A. Opening and duration of the session ............................................................... 1–3 7 B. Attendance ...................................................................................................... 4 7 C. Agenda and programme of work -

082404 Cover

“A celebration of committed individuals who serve as building blocks in the lives of children” Thursday, September 23, 2004 Washington, DC 2 ach year, the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute, CCAI, invites Members of Congress to recognize those individuals who have made a difference in the lives of orphans and foster children by giving them the Congressional Angels in Adoption™ Award. CCAI is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to raising awareness about the tens of thousands of foster children in this country and the millions of orphans around the world in need of permanent, safe, and loving homes; and to eliminating the barriers that hinder these children from realizing their basic need of a family. 2004 Congressional Awards Celebration Welcome Delilah National Radio Personality Musical Performance Watoto Children’s Choir Kampala, Uganda Message from CCAI President Senator Mary Landrieu Congressional Director, CCAI Message from Founding and Maxine B. Baker Premier Sponsor President and CEO, Freddie Mac Foundation Musical Performance Steven Curtis Chapman Recording Artist/Song Writer Guardian Angel Recognition Kerry Marks Hasenbalg Executive Director, CCAI Invocation Barry Black Chaplain of the United States Senate Recognition of 2004 Angels in Adoption™ Congressional Leadership Dinner Recognition of Congressional Members Delilah Presentation of National Angel in Adoption™ Congressman Jim Oberstar Award to Pat and Ruth Williams Congressional Director, CCAI Presentation of National Angel in Adoption™ Congressman -

International Adoption: the Most Logical Solution to the Disparity

INTERNATIONAL ADOPTION: THE MOST LOGICAL SOLUTION TO THE DISPARITY BETWEEN THE NUMBERS OF ORPHANED AND ABANDONED CHILDREN IN SOME COUNTRIES AND FAMILIES AND INDIVIDUALS WISHING TO ADOPT IN OTHERS? Sara R. Wallace* I. INTRODUCTION Throughout the world there are millions of children who lack families, homes, and basic care.1 This problem is especially pronounced in countries where war or national disasters have taken a devastating economic toll on families.2 Many families who cannot afford to provide for their children are left with no choice but to abandon them out of need or shame.3 As a result, many children are left to the streets. For example, up to seven million “meninos da rua” (Portuguese for “children of the street”) live on the streets in Brazil’s large cities.4 Non-economic factors also contribute to children becoming orphans. Social and political circumstances have left children without families. In China, for instance, the One-Child Policy, coupled with Chinese culture’s preference for male children, leads families to abandon or give up for adoption thousands of first-born female children.5 The Korean War left thousands of children in that country homeless.6 Confucian beliefs that emphasize continuance of the family through an unbroken bloodline dissuaded Koreans from adopting children unrelated to them.7 Under the Ceausescu regime in Romania, women were forced * J.D. Candidate, University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law, 2004; Master of Science in Family Studies and Human Development, University of Arizona, 2001; Bachelor of Arts in Psychology, Pepperdine University, 1998. I wish to thank DeAnna Rivera and Rebecca Papoff for their support and thoughtful editing, as well as my friends and family for their continuing encouragement. -

The Situation of Minority Children in Russia

The Situation of Children Belonging to Vulnerable Groups in Russia Alternative Report March 2013 Anti- Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL” The NGO, Anti-Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL”, was registered in 2007 and continued work on a number of human rights and anti-discrimination projects previously coordinated by the Charitable Educational Human Rights NGO “MEMORIAL” of St. Petersburg. ADC “Memorial‟s mission is to defend the rights of individuals subject to or at risk of discrimination by providing a proactive response to human rights violations, including legal assistance, human rights education, research, and publications. ADC Memorial‟s strategic goals are the total eradication of discrimination at state level; the adoption of anti- discrimination legislation in Russia; overcoming all forms of racism and nationalism; Human Rights education; and building tolerance among the Russian people. ADC Memorial‟s vision is the recognition of non-discrimination as a precondition for the realization of all the rights of each person. Tel: +7 (812) 317-89-30 E-mail: [email protected] Contributors The report has been prepared by Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” with editorial direction of Stephania Kulaeva and Olga Abramenko. Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” would like to thank Simon Papuashvili of International Partnership for Human Rights for his assistance in putting this report together and Ksenia Orlova of ADC “Memorial” for allowing us to use the picture for the cover page. Page 2 of 47 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 7 Overview of the legal and policy initiatives implemented in the reporting period ................. 11 Violations of the rights of children involving law enforcement agencies ............................... -

Russia Bans U.S. Adoptions

Dear Class Member, This is the lesson we will address this week: Jan. 6. We will meet in Fellowship Hall. See you on Sunday....bring your prayers, questions, ideas, thoughts of how we can make a difference Blessings, Fran Russia Bans U.S. Adoptions Claiming that Americans routinely mistreat adoptees from his country, Russian president Vladimir Putin supported a law that would halt the adoption of Russian children by U.S. families. Both houses of the Russian Parliament voted overwhelmingly to approve the measure, citing 19 deaths of Russian children by their American adoptive parents since the 1990s. The bill was named for Dima Yakovlev, a toddler whose blind grandmother claimed was illegally adopted by Americans who first forged her signature on adoption documents and then left him for hours in a broiling hot car, leading to his death. The adoptive father was found not guilty of involuntary manslaughter. A few lawmakers claimed that some Russian children were adopted by Americans to be used for organ transplants and to become sex toys or cannon fodder for the U.S. Army. In 2010, an American woman sent her adopted son back to Russia alone on a plane, claiming that the then-7-year-old boy had violent episodes that made the family fear for its safety. Lawmakers also expressed the concern that foreign adoptions discourage Russians from adopting children. Russian law allows foreigners to adopt only if a Russian family has not expressed interest in a child being considered for adoption, but “a foreigner who has paid for an adoption always gets a priority compared to potential Russian adoptive parents,” said Russian children’s rights ombudsman Pavel Astakhov. -

Fixing Broken Families in Post-Soviet Russia

p022-23_June 13_PSW_templates 23/05/2013 15:39 Page 14 Professional Social Work • June 2013 22 Russia Fixing broken families in post-Soviet Russia Until recently, Russia believed unwanted children were best cared for in the country’s vast network of orphanages. Now, however, adoption and fostering are increasingly seen as the answer. Sue Kent travelled to Dzerzhinsk with BASW’s Russian Network Group to visit a project trying to unite families. or decades, it was Russia’s hidden vast institutional care system. Many of the so- relative infancy and professionals working with shame: hundreds of thousands of called orphans are disabled. The rest are children and families are looking to countries in F children abandoned in huge children who are not wanted or cannot be cared the west for guidance. government-run care homes, for by their parents or have suffered abuse or In May, members of BASW’s Russian often with little stimulation or neglect. Network Group visited Dzerzhinsk, a city in experience of the outside world. According to Today, however, things are changing, and central Russia. The aim of the trip was to meet estimates, some 700,000 children currently live Russia’s orphanages are opening up. In 2010, Russian colleagues and evaluate a social work- in about 2,000 state-run orphanages where then President Dmitry Medvedev, announced led project which is seeking to prevent family resident populations can be as high as 400. there should be no orphans in Russia, breakdown and avoid children being taken into These children are not orphans as we proclaiming: “Guardianship must be directly care. -

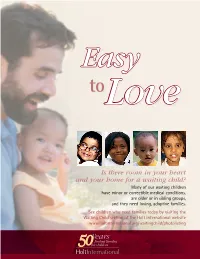

Is There Room in Your Heart and Your Home for a Waiting Child?

Easy toLove Is there room in your heart and your home for a waiting child? Many of our waiting children have minor or correctible medical conditions, are older or in sibling groups, and they need loving, adoptive families. See children who need families today by visiting the Waiting Child section of the Holt International website www.holtinternational.org/waitingchild/photolisting finding families for children Dear Readers Christina* greeted me a few years ago at the home of her foster family in Romania. She was 12 years old, with dark eyes, and dark hair pulled back into a SUMMER 2006 VOL. 48 NO. 3 HOLT INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S SERVICES ponytail that framed her pretty face. I was surprised by how normal and healthy P.O. Box 2880 (1195 City View) Eugene, OR 97402 she looked. Ph: 541/687.2202 Fax: 541/683.6175 OUR MISSION I expected her to look, well… sick. After all, Christina was HIV-positive. Instead I Holt International is dedicated to carrying out God’s plan for every child to have a permanent, loving family. found a girl on the cusp of adolescence who wore the unadorned, fresh beauty of In 1955 Harry and Bertha Holt responded to the conviction that youth. God had called them to help children left homeless by the Korean War. Though it took an act of the U.S. Congress, the Holts adopt- “So this is the face of AIDS,” I marveled. ed eight of those children. But they were moved by the desperate plight of other orphaned children in Korea and other countries In this issue of Holt International magazine, we feature a look at the range of as well, so they founded Holt International Children’s Services in order to unite homeless children with families who would love work Holt is doing around the world for children affected by HIV/AIDS. -

Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests

Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol, Coordinator Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs March 5, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33407 Russian Political, Economic, and Security Issues and U.S. Interests Summary Russia made uneven progress in democratization during the 1990s, but this limited progress was reversed after Vladimir Putin rose to power in 1999-2000, according to many observers. During this period, the State Duma (lower legislative chamber) became dominated by government- approved parties, gubernatorial elections were abolished, and the government consolidated ownership or control over major media and industries, including the energy sector. The Putin government showed low regard for the rule of law and human rights in suppressing insurgency in the North Caucasus, according to critics. Dmitry Medvedev, Putin’s longtime protégé, was elected president in 2008; President Medvedev immediately designated Putin as prime minister and continued Putin’s policies. In August 2008, the Medvedev-Putin “tandem” directed military operations against Georgia and recognized the independence of Georgia’s separatist South Ossetia and Abkhazia, actions condemned by most of the international community. In late 2011, Putin announced that he would return to the presidency and Medvedev would become prime minister. This announcement, and flawed Duma elections at the end of the year, spurred popular protests, which the government addressed by launching a few reforms and holding pro-Putin rallies. In March 2012, Putin was (re)elected president by a wide margin. The day after Putin’s inauguration in May 2012, the legislature confirmed Medvedev as prime minister. -

Russia 2019 Human Rights Report

RUSSIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Russian Federation has a highly centralized, authoritarian political system dominated by President Vladimir Putin. The bicameral Federal Assembly consists of a directly elected lower house (State Duma) and an appointed upper house (Federation Council), both of which lack independence from the executive. The 2016 State Duma elections and the 2018 presidential election were marked by accusations of government interference and manipulation of the electoral process, including the exclusion of meaningful opposition candidates. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Investigative Committee, the Office of the Prosecutor General, and the National Guard are responsible for law enforcement. The FSB is responsible for state security, counterintelligence, and counterterrorism as well as for fighting organized crime and corruption. The national police force, under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, is responsible for combating all crime. The National Guard assists the FSB Border Guard Service in securing borders, administers gun control, combats terrorism and organized crime, protects public order, and guards important state facilities. The National Guard also participates in armed defense of the country’s territory in coordination with Ministry of Defense forces. Except in rare cases, security forces generally reported to civilian authorities. National-level civilian authorities, however, had, at best, limited control over security forces in the Republic of Chechnya, which were accountable only to the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov. The country’s occupation and purported annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula continued to affect the human rights situation there significantly and negatively. The Russian government continued to arm, train, lead, and fight alongside Russia-led forces in eastern Ukraine.