Adebaran Vol.4 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Breach Video Series Study Guide

Into the Breach Video Series Study Guide Faith in Action Faith Into the Breach Video Series Study Guide Copyright © Knights of Columbus, 2021. All rights reserved. Quotations from Into the Breach, An Apostolic Exhortation to Catholic Men, Copyright © 2015, are used with permission of Diocese of Phoenix. Quotations from New American Bible, Revised Edition, Copyright © 2010, are used with permission of Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. Quotations from Catholic Word Book #371, Copyright © 2007, are used with permission of Knights of Columbus Supreme Council and Our Sunday Visitor, Huntington, IN 46750. Cover photograph credit: Shutterstock. Russo, Alex. Saint Michael Archangel statue on the top of Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome, Italy, used with permission. Getty Images. Trood, David. Trekking in the Austrian Alps, used with permission. No part of this booklet may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS Introduction. 1 A Man Who Can Stand in the Breach. 2 How to Use This Study Guide . 3 How to Lead a Small Group Session . 8 INTO THE BREACH EPISODES Masculinity . 12 Brotherhood. 19 Leadership . 27 Fatherhood. 35 Family . 42 Life . 49 Prayer . 56 Suffering . 64 Sacramental Life . 72 Spiritual Warfare . 80 Evangelization . 87 The Cornerstone . 95 APPENDIX Definitions . 103 Catholic Information Service. 107 Faith in Action . 108 INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS Introduction “And I sought for a man among them who should build up the wall and stand in the breach before me for the land…” (Ezekiel 22:30) In 2015, Bishop Thomas J. -

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

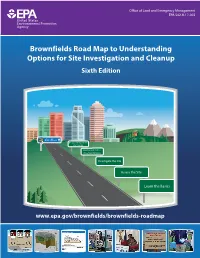

Epa 542-R-17-003

Oce of Land and Emergency Management EPA 542-R-17-003 Brownf ields Road Map to Understanding Options for Site Investigation and Cleanup Sixth Edition Site Reuse Design and Implement the Cleanup Assess and Select Cleanup Options Investigate the Site Assess the Site Learn the Basics www.epa.gov/brownfields/brownfields-roadmap [This page is intentonally left blank] Table of Contents Brownfields Road Map Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Follow the Brownfields Road Map ...................................................................................... 6 Learn the Basics .................................................................................................................. 9 Assess the Site ................................................................................................................... 20 Investigate the Site ........................................................................................................... 26 Assess and Select Cleanup Options ................................................................................... 36 Design and Implement the Cleanup ................................................................................. 43 Spotlights 1 Innovations in Contracting ................................................................................... 18 2 Supporting Tribal Revitalization ........................................................................... 19 -

Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 1 - - 2 - Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea The Representation of Black Heroism in American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 4 - Table of Contents: Preface Chapter One: The Western Victimization of African Americans during and after Slavery 1.1 – Visual Culture in Propaganda 1.2 - African Americans as Victims of the System of Slavery 1.3 - The Gift of Freedom 1.4 - The Influence of White Stereotypes on the Perception of Blacks 1.5 - Racial Discrimination in Criminal Justice 1.6 - Conclusion Chapter Two: Black Heroism in Modern American Cinema 2.1 – Representing Racial Agency Through Passive Characters 2.2 - Django Unchained: The Frontier Hero in Black Cinema 2.3 - Character Development in Django Unchained 2.4 - The White Savior Narrative in Hollywood's Cinema 2.5 - The Depiction of Black Agency in Hollywood's Cinema 2.6 - Conclusion Chapter Three: The Different Interpretations -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death -

Modes and Monikers

Modes and Monikers Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree in Fine Arts the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Zachary Podgorny Graduate Program in Art The Ohio State University 2011 Committee: Suzanne Silver- “Advisor” Laura Lisbon Ann Hamilton Michael Mercil Copyright by Zachary Podgorny Year of Graduation 2011 Abstract My work reflects the various modes of making in which I engage: painting and drawing, alongside playing of the violin, cooking, impromptu rhyming in English and Russian, the manipulation of recorded sounds, the movement of my body, and collaborating with other artists, musicians and dancers. I investigate the material narrative that takes place in my painting and drawing. This includes the marinating and cooking of different oils, pigments, and balsams as they are applied to different kinds of surfaces. Recently I have painted on linen, plastic shower curtains, window curtains, blankets, fencing, different types of paper, and most recently dry wall. I believe that an engagement with these surfaces inform the way I approach my painting. I believe that the kind of play, thinking, and processing that takes place in my painting is reflected in my other approaches to making. I have assumed different personae. These personas have been named. These monikers are attributed to each mode of making. ii Dedication This is dedicated to my Yelena Podgorny; my mother, Genya Vaks; my grandmother, and Anna Podgorny; my sister. They are the most important people in my life. I also dedicate this work to the memory of my grandfather Mendel Vaks. iii Acknowledgments Dear Suzanne Thank you so much for making me feel welcome. -

Thunderstorm at Michael’S House

TRUST AND TEAMWORK A 9/11 Story of Courage, Vision, and a Dog Named Roselle Michael Hingson with Susy Flory TRUST AND TEAMWORK – Hingson/Flory 2 TRUST AND TEAMWORK A 9/11 Story of Courage, Vision, and a Dog Named Roselle “We can do most anything we want to do.” Michael Hingson Go inside the stairwell of Tower One in TRUST AND TEAMWORK as Michael Hingson and his guide dog, Roselle, fight their way down 78 flights of stairs through the blistering heat of the fires and the smell of jet fuel to survive the World Trade Center bombing. Michael’s blindness didn’t stop him from shocking the neighbors by riding his bicycle through the streets of Palmdale, California as a child, and on September 11 his blindness became an asset as he successfully led a group of people to safety during the worst terrorist attack ever on American soil. 1. CONTENT A. The ten year anniversary of 9/11 is coming up! What’s new here? ~ Ten years later, the Michael Hingson story helps to bring some closure and make sense of the events of September 11. The time is right for an extraordinary story of an unlikely hero. ~ The events of 9-11 still haunt the American imagination, especially in light of the continued threat of terrorism and the recent attempted car bombing in Times Square. Michael Hingson’s story is an antidote; it’s positive, redemptive, compelling, and has a happy ending. In addition, the ~ Each chapter includes life lessons learned from Michael’s unique and heroic 9-11 experience, with additional material woven in related to growing up blind, working with a guide dog, his marriage to a woman in a wheelchair, and successfully functioning with a major disability. -

An Analysis of Paternalistic Objections to Hate Speech Regulation

ESSAY II Pressure Valves and Bloodied Chickens: An Analysis of Paternalistic Objections to Hate Speech Regulation Richard Delgadot David H. YunT INTRODUCTION The dominant free speech paradigm's resistance to change is not the only obstacle that hate speech rule advocates confront: what we call pater- nalistic objections are deployed as well to discourage reform, ostensibly in minorities' best interest.1 These paternalistic arguments all urge that hate speech rules would harm their intended beneficiaries, and thus, if blacks and other minorities knew their own self-interest, they would oppose such rules. Often the objections take the form of arguing that there is no conflict between equality and liberty, since by protecting speech one is also protect- ing minorities.2 This Essay details and answers these arguments before suggesting potential avenues for reform in the near future. Copyright © 1994 California Law Review, Inc. t Charles Inglis Thomson Professor of Law, University of Colorado. J.D. 1974, University of California, Berkeley. * Member of the Colorado Bar. J.D. 1993, University of Colorado. 1. By paternalism, we mean a justification for curtailing someone's liberty that invokes the well- being of the person concerned, that is,that requires him or her to do or refrain from doing something for his or her own good. Could it be argued that the opposite position, namely advocacy of hate speech regulation, is also paternalistic, in that it implies that minorities need or want protection, when many may not? No. The impetus for such regulation comes mainly from minority attorneys and scholars. See, e.g., Charles R. -

Doherty, Thomas, Cold War, Cool Medium: Television, Mccarthyism

doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page i COLD WAR, COOL MEDIUM TELEVISION, McCARTHYISM, AND AMERICAN CULTURE doherty_FM 8/21/03 3:20 PM Page ii Film and Culture A series of Columbia University Press Edited by John Belton What Made Pistachio Nuts? Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic Henry Jenkins Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle Martin Rubin Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II Thomas Doherty Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy William Paul Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s Ed Sikov Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema Rey Chow The Cinema of Max Ophuls: Magisterial Vision and the Figure of Woman Susan M. White Black Women as Cultural Readers Jacqueline Bobo Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Film Darrell William Davis Attack of the Leading Ladies: Gender, Sexuality, and Spectatorship in Classic Horror Cinema Rhona J. Berenstein This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age Gaylyn Studlar Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond Robin Wood The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music Jeff Smith Orson Welles, Shakespeare, and Popular Culture Michael Anderegg Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, ‒ Thomas Doherty Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity James Lastra Melodrama and Modernity: Early Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts Ben Singer -

January 2017 Heroes of Hope Newsletter (PDF)

THE CHILDREN'S CENTER NEWSLETTER VOL. 2, NO. 1 | JANUARY 2017 WELCOME TO HEROES OF HOPE! You have something in common with the children and families we serve. You’re both heroes. You are courageous. You are generous. You believe, like we do, that when you lift a child’s spirit – you ultimately lift an entire community. We dedicate this inaugural edition of Heroes of Hope to you. Each month, we’ll be sharing a glimpse into how your support is making a measurable difference in the lives of children and families who have experienced unimaginable challenges. You’ll see how they are rising above those challenges with the help of the mental and behavioral health services from The Children’s Center. On occasion, we’ll highlight some of you in the hope of shining a light on your extraordinary commitment to helping Detroit’s vulnerable children heal, grow and thrive. Your biggest fan, Debora Matthews | President & CEO, The Children’s Center • Welcome from Debora Matthews • Holiday Shop Brings Joy IN THIS ISSUE: • Carls Foundation Makes a Difference • Parade Fun • Thanksgiving Meals for All • The Children’s Center Wish List PARADE FUN! Generous individuals like you along with The Parade Company sponsored children and families served by The Children’s Center to participate in America’s Thanksgiving Day Parade Clowns for Kids program. Special thanks to Jason Lambiris, a distinguished clown himself and beloved Board Member, for founding this program! HOLLINGSWORTH LOGISTICS GROUP EMPLOYEES DROP OFF COMPLETED CLINICIAN KITS TO THE CHILDREN’S CENTER STAFF. LOOK AT ALL THOSE TOOLS THAT WILL HELP CHILDREN SHAPE THEIR OWN FUTURES CARLS FOUNDATION MAKES A DIFFERENCE WITH CLINICIAN KITS If you could dig into a clinician kit, you’d find chunky puzzles that help children learn motor skills. -

Knowledge PHILOSOPHY for HEROES PART I: KNOWLEDGE

Philosophy for Heroes Part I: Knowledge PHILOSOPHY FOR HEROES PART I: KNOWLEDGE Published by Clemens Lode Verlag e.K., Düsseldorf Book Series Philosophy for Heroes Part I: Knowledge Part II: Continuum Part III: Act Part IV: Epos © 2016 Clemens Lode Verlag e.K., Düsseldorf All Rights Reserved. https://www.lode.de For more information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected]. 2016, First Edition ISBN 978-3-945586-21-1 Edited by: Conna Craig Cover design: Jessica Keatting Graphic Design Image sources: Shutterstock, iStockphoto Icons made by http://www.freepik.com from http://www.flaticon.com is licensed by CC 3.0 BY (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) Printed on acid-free, unbleached paper. Subscribe to our newsletter. Simply write to [email protected] or visit our website https://www.lode.de. PHILOSOPHY POPULAR SCIENCE PSYCHOLOGY Dedication We are, each of us, privileged to live a life that has been touched by many heroes. They possessed extraordinary gifts, and they shared them with us freely. None of these “ gifts were more remarkable than their ability to discern what needed to be done, and their unfailing courage in doing it and speaking the truth, whatever the personal cost. Let us each strive to accept their gifts and pass them along, asan ongoing tribute to the wise men and women of our human history who taught us all how to be heroes. Do not let the hero in your soul perish in lonely frustration for the life you deserve, but have never been able to reach.