Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Minority Report 2018

theMINORITYREPORT The annual news of the AEA’s Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession, the National Economic Association, and the American Society of Hispanic Economists Issue 10 | Winter 2018 HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES AND HISPANIC-SERVING INSTITUTIONS ARE A RICH SOURCE FOR THE ECONOMICS PIPELINE By Rhonda V. Sharpe, Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race, and Omari H. Swinton, Howard University The US Census Bureau projects that by 2060, 57 percent of the US population will identify as racially nonwhite or as ethnically Hispanic.1 As the United States becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, a diverse population of economists will be crucial to ensuring that economic analysis and policy recommendations are inclusive of the needs of all Americans. As we show below, historically black colleges and universities and Hispanic-serving institutions can be a rich pipeline for building a more inclusive economics field. WHAT DEFINES HISTORICALLY BLACK The “prior to 1964” requirement is significant because COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES AND Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal HISPANIC-SERVING INSTITUTIONS? to discriminate because of color, race, or national origin. Therefore, all institutions of higher education The Higher Education Act of 1965 (as amended) defines established after 1964 would have been open to blacks. a historically black college or university as: Unlike historically black colleges and universities or tribal Any historically black college or university that was colleges and universities, classification as an HSI is not established prior to 1964, whose principal mission based on an institution’s mission at its point of origin was, and is, the education of black Americans, but on whom it serves, which in turn is influenced by the and that is accredited by a nationally recognized demographics of its location. -

Wild Bulls, Discarded Foreigners, and Brash Champions: US Empire and the Cultural Constructions of Argentine Boxers Daniel Fridman & David Sheinin

Wild Bulls, Discarded Foreigners, and Brash Champions: US Empire and the Cultural Constructions of Argentine Boxers Daniel Fridman & David Sheinin In the past decade, scholars have devoted growing attention to American cultural influences and impact in the Philippines, Panama, and other societies where the United States exerted violent imperial influences.1 In countries where US imperi- alism was less devastating to local political cultures, the nature of American cultur- al influence and the impact such force had is less clear and less well documented.2 Argentina is one such example. American political and cultural influences in twen- tieth-century Argentina cannot be equated with the cases of Mexico or the Dominican Republic, nor can they be said to have had as profound an impact on national cultures. At the same time, after 1900, US cultural influences were perva- sive in and had a lasting impact on Argentina. There is, to be sure, a danger of trivializing the force of American Empire by confusing Argentines with Filipinos as subject peoples. Argentina is not a “classic” case of US imperialism in Latin America. While the United States supported the 1976 coup d’état in Argentina, for example, there is no evidence of Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and US military backing on a scale equivalent to the 1964 military coup in Brazil or the 1973 overthrow of democracy in Chile. Although American weapons and military strategies were employed by the Argentine armed forces in state terror operations after 1960, there was no Argentine equivalent -

The Safety of BKB in a Modern Age

The Safety of BKB in a modern age Stu Armstrong 1 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© www.stuarmstrong.com Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 The Author .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Why write this paper? ......................................................................................................................... 3 The Safety of BKB in a modern age ................................................................................................... 3 Pugilistic Dementia ............................................................................................................................. 4 The Marquis of Queensbury Rules’ (1867) ......................................................................................... 4 The London Prize Ring Rules (1743) ................................................................................................. 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 8 2 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© -

Boxing Edition

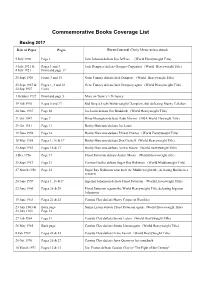

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

November 2020 Newsletter Calling for Further Support for Welsh Businesses and Communities During the Pandemic

Gerald Jones MP Putting Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney at the heart of Parliament November 2020 Newsletter Calling for further support for Welsh businesses and communities during the pandemic So far during the pandemic, the Welsh Government has done everything it can to support Welsh businesses and communities, and ensure they have what they need to get through this hugely challenging time, working closely together with local authorities and the third sector throughout. This is in stark contrast to what we’ve seen so far from the UK Government, however, and speaking in Parliament last month I praised the inclusive approach taken in Wales and called on the UK Government to step up and provide further much-needed support for communities in Wales and right across the UK. Calling on the Chancellor to bring forward urgent further support for Both Scotland and parts Welsh businesses and communities, 22nd October of northern England have had the same treatment as Wales, denied additional help or flexibility with support schemes as stricter lockdown measures have come into force, and I’ve called on the Government several times in the past few weeks to ensure there’s equality across the UK and nobody’s excluded from help who needs it. Despite this, however, our communities have shown huge resilience and spirit to support each other, with the voluntary and housing sectors also doing incredible work to help and protect those most in need, and speaking in Parliament last month, I paid tribute to all the amazing efforts and community spirit we’ve seen so far. -

Bibliografía Histórica Mexicana

BIBLIOGRAF?A HIST?RICA MEXICANA Susana UR1BE DE FERNANDEZ DE C?RDOBA El Colegio de M?xico INDICE 1. Estudios bibliogr? 10. Historia Social 12191-12233 ficos 11478-11517 11. Historia del De 2. Historia General 11518-11669 recho 12234-12247 3. Historiograf?a 11670-11700 12. Historia Di p?o m? 4. Historia Prehisp? tica 12248-12290 nica 11701-11807 13. Historia Literaria 12291-12350 5. Historia Pol?tica 11808-11976 14. Historia del Arte 12351-12395 6. Historias Particu 15. Historia de la lares 11977-12051 Ciencia 12396-12403 7. Historia de la Fi 16. Historia de la losof?a y las Ideas 12052-12067 Educaci?n 12404-12416 8. Historia Religiosa 12068-12116 17. Testimonios perso 9. Historia Econ?mi nales 12417-12432 ca 12117-12190 18. Folklore 12433-12450 1. ESTUDIOS BIBLIOGR?FICOS 11478. Ayala Ech?varri, Rafael?Bibliograf?a hist?rica y geogr?fica de Quer?taro.?Quer?taro, 1965. vil, 80 pp. 11479. Banco de M?xico, S. A. Departamento de Estudios Econ?micos. Biblioteca.?Bibliograf?a Econ?mica de M?xico (1958-1962).? M?xico, Banco de M?xico, S. A., 1964. 11480. Bolet?n Bibliogr?fico de Antropolog?a Americana.?fy??xico, Insti tuto Panamericano de Geograf?a e Historia. Comisi?n de Historia.? Vols. 21-22. M?xico, 1962. 11481. Dillon, Richard H.?"Sutro Library's resources in Latin Amer ica".?HAHR, XLV (1965), pp. 261-21 A. 11482. Handbook of Latin American Studies, N<? 26. Edited by Earl J. Pariseau. Gainesville, The University of Florida Press, 1964 259 pp. This content downloaded from 132.248.9.41 on Wed, 10 Feb 2021 22:43:16 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 94 SUSANA U. -

Fight Year Duration (Mins)

Fight Year Duration (mins) 1921 Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (23:10) 1921 23 1932 Max Schmeling vs Mickey Walker (23:17) 1932 23 1933 Primo Carnera vs Jack Sharkey-II (23:15) 1933 23 1933 Max Schmeling vs Max Baer (23:18) 1933 23 1934 Max Baer vs Primo Carnera (24:19) 1934 25 1936 Tony Canzoneri vs Jimmy McLarnin (19:11) 1936 20 1938 James J. Braddock vs Tommy Farr (20:00) 1938 20 1940 Joe Louis vs Arturo Godoy-I (23:09) 1940 23 1940 Max Baer vs Pat Comiskey (10:06) – 15 min 1940 10 1940 Max Baer vs Tony Galento (20:48) 1940 21 1941 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-I (23:46) 1941 24 1946 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-II (21:48) 1946 22 1950 Joe Louis vs Ezzard Charles (1:04:45) - 1HR 1950 65 version also available 1950 Sandy Saddler vs Charley Riley (47:21) 1950 47 1951 Rocky Marciano vs Rex Layne (17:10) 1951 17 1951 Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano (23:55) 1951 24 1951 Kid Gavilan vs Billy Graham-III (47:34) 1951 48 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Jake LaMotta-VI (47:30) 1951 47 1951 Harry “Kid” Matthews vs Danny Nardico (40:00) 1951 40 1951 Harry Matthews vs Bob Murphy (23:11) 1951 23 1951 Joe Louis vs Cesar Brion (43:32) 1951 44 1951 Joey Maxim vs Bob Murphy (47:07) 1951 47 1951 Ezzard Charles vs Joe Walcott-II & III (21:45) 1951 21 1951 Archie Moore vs Jimmy Bivins-V (22:48) 1951 23 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Randy Turpin-II (19:48) 1951 20 1952 Billy Graham vs Joey Giardello-II (22:53) 1952 23 1952 Jake LaMotta vs Eugene Hairston-II (41:15) 1952 41 1952 Rocky Graziano vs Chuck Davey (45:30) 1952 46 1952 Rocky Marciano vs Joe Walcott-I (47:13) 1952 -

Guía De Preinscripción Para Educación Básica (SAID)

Guía de Preinscripción para Educación Básica (SAID) Este año se ha implementado para la preinscripción en los niveles preescolar, primaria y secundaria de 33 municipios del Estado de México el SAID (Sistema Anticipado de Inscripción y Distribución) vía internet. Si vas a preinscribir a tu hijo(a) en alguna de las escuelas incluidas en el SAID, te sugerimos primero consultes esta guía informativa. Contenido 1. Teléfonos de ayuda 2. Convocatoria de Preinscripción 3. Errores más comunes 4. Catálogo de escuelas * Da clic en el índice para ir directamente a la sección que deseas Teléfonos de ayuda Si tienes algún problema o duda del SAID (Sistema Anticipado de Inscripción y Distribución) te pedimos te comuniques al teléfono 070 en el valle de Toluca y al 01800 696 9696 en el resto de estado. IMPORTANTE: Si la escuela que te interesa ESTÁ en la lista para hacer tu preinscripción por Internet, NO podrás hacerla físicamente. Manténte informado sobre el SAID a través de la cuenta de Twitter del Gobierno del Estado de México @edomx http://twitter.com/edomx Gobierno del Estado de México: SAID 2010 http://saidedomex.wordpress.com/ Síguenos en Twitter http://twitter.com/edomx Convocatoria La Secretaría de Educación del Gobierno del Estado de México convoca a realizar preinscripciones de preescolar, primaria y secundaria. I. Periodo de atención Calendario de Preinscripciones Al SAID sólo podrás ingresar vía internet el día de corresponda a la primera letra del apellido de tu hijo(a). Este calendario del SAID es igual para las personas que se van a preinscribir por internet y para los que van a hacerlo de la manera tradicional. -

Translated Excerpt Reinhard Kleist Knock Out!

Translated excerpt Reinhard Kleist Knock Out! Die Geschichte von Emile Griffith Carlsen Verlag, Hamburg 2019 ISBN 978-3-551-73363-4 pp. 84-104 Reinhard Kleist Knock Out! The Story of Emile Griffith Translated by Michael Waaler © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 2020 Litrix.de Knock Out! © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 2020 Litrix.de 1 GET RID OF THEM!!! IT’S MR. CLANCY. WHY CAN’T THEY JUST LEAVE ME ON PEACE?!? © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 84 2020 Litrix.de 2 I’M SORRY THAT YOU’VE COME ALL THIS WAY FOR NOTHING AGAIN, MR. CLANCY. I DON’T WANT TO SEE ANYONE! TELL HIM, I UNDERSTAND AND THAT HE KNOWS WHERE TO FIND ME. MOMMY ALWAYS TAKES CARE OF ME. © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 85 2020 Litrix.de 3 HI. © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 86 2020 Litrix.de 4 GOOD IDEA. SORRY, OTHERWISE, YOU’D I DON’T CLANCY, I GOT BE THE FIRST IN EVEN WANNA TO GO HOME MY CLUB TO BOX BOX... I JUST AGAIN. I FORGOT NAKED! WANNA...… MY LOCKER KEY. WHY YOU STANDING AROUND LIKE THAT, KID? NOT WHAT? BE HOME ALONE. CAN’T WE PING-PONG? WELL, OKAY OKAY THEN. JUST PLAY NOW YOU THEN. TWO LET’S WORK ON PING-PONG WANNA PLAY DOLLARS FOR YOUR LEG WORK, INSTEAD? PING-PONG!?! THE WINNER! OKAY? © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 87 2020 Litrix.de 5 © 2019 Carlsen Verlag / © 88 2020 Litrix.de 6 HEY! THAT WAS NET, CLANCY!! I STILL WON. HAND OVER MY TWO DOLLARS! THERE’S THE EMILE THEN I KNOW, NOT THE ONE JUST I WANNA WHO SLUNK IN HERE GIVE ME REMATCH! A MOMENT AGO. -

The Structure of Meaning in the Boxing Film Genre Author(S): Leger Grindon Source: Cinema Journal, Vol

Society for Cinema & Media Studies Body and Soul: The Structure of Meaning in the Boxing Film Genre Author(s): Leger Grindon Source: Cinema Journal, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Summer, 1996), pp. 54-69 Published by: University of Texas Press on behalf of the Society for Cinema & Media Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1225717 Accessed: 10-12-2016 07:09 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Society for Cinema & Media Studies, University of Texas Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cinema Journal This content downloaded from 129.100.58.76 on Sat, 10 Dec 2016 07:09:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Body and Soul: The Structure of Meaning in the Boxing Film Genre by Leger Grindon This essay focuses on the master plots, characterizations, settings, and genre his- tory of boxing in Hollywood fiction films since 1930. The boxer and boxing are significant figures in the Hollywood cinema, with ap- pearances in well over 150 feature-length fiction productions since 1930.1 During the decade 1975 to 1985 the screen boxer was prominent with, on the one hand, the enormous commercial success of the Rocky series and, on the other, the criti- cal esteem garnered by Raging Bull (1980). -

Dmitriy Salita

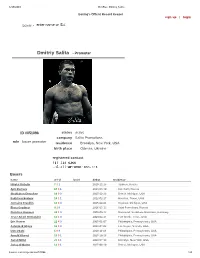

6/18/2019 BoxRec: Dmitriy Salita Boxing's Official Record Keeper sign up | login enter name or ID# boxer ▾ Dmitriy Salita - Promoter ID #051096 status active company Salita Promotions role boxer promoter residence Brooklyn, New York, USA birth place Odessa, Ukraine registered contact Boxers name w-l-d last 6 debut residence Nikolai Buzolin 7 3 1 2010-12-15 Tyumen, Russia Apti Davtaev 17 0 1 2013-03-30 Kurchaloi, Russia Shohjahon Ergashev 16 0 0 2015-12-23 Detroit, Michigan, USA Bakhtiyar Eyubov 14 1 1 2012-02-17 Houston, Texas, USA Jermaine Franklin 18 0 0 2015-04-04 Saginaw, Michigan, USA Elena Gradinar 9 1 0 2016-05-13 Saint Petersburg, Russia Christina Hammer 24 1 0 2009-09-12 Dortmund, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany Jesse Angel Hernandez 12 3 0 2009-02-14 Fort Worth, Texas, USA Eric Hunter 21 4 0 2005-01-07 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Aslambek Idigov 16 0 0 2013-07-02 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Izim Izbaki 1 0 0 2018-11-16 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Arnold Khegai 15 0 1 2015-10-28 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Jarrell Miller 23 0 1 2009-07-18 Brooklyn, New York, USA Jarico O'Quinn 12 0 1 2015-04-10 Detroit, Michigan, USA boxrec.com/en/promoter/51096 1/4 6/18/2019 BoxRec: Dmitriy Salita name w-l-d last 6 debut residence Samuel Peter 38 7 0 2001-02-06 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA Nikolai Potapov 20 1 1 2010-03-13 Brooklyn, New York, USA Umar Salamov 24 1 0 2012-12-15 Henderson, Nevada, USA Elena Saveleva 5 1 0 2017-06-23 Pushkino, Russia Claressa Shields 9 0 0 2016-11-19 Flint, Michigan, USA Vladimir Shishkin 8 0 0 2016-07-31 Serpukhov, -

Wales Area Title Bouts 1929-79

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved http://www.boxinghistory.org.uk Wales Area Title Bouts 1929-79 Flyweight Mar 2 1929 Merthyr Phineas John (Pentre) WPTS(15) Jerry O'Neill (Merthyr) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title) Jul 22 1929 Pontypridd Palais de Danse Freddie Morgan (Gilfach Goch) WPTS(15) Phineas John (Pentre) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title) Dec 23 1929 Pontypridd Palais de Danse Freddy Morgan (Gilfach Goch) DRAW(15) Young Beckett (Pentre) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title) Jul 12 1930 Merthyr Jerry O'Neill (Merthyr) WDSQ4(15) Freddy Morgan (Gilfach Goch) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title) Jan 10 1931 Ammanford Pavilion Len Beynon (Swansea) WPTS(15) George Morgan (Newport) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title Eliminator) Mar 7 1931 Swansea Shaftesbury Theatre Fred Morgan (Gilfach Goch) WPTS(15) Len Beynon (Swansea) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title) Aug 1 1931 Ammanford Pavilion Cliff Peregrine (Ammanford) WDSQ3(15) Len Beynon (Swansea) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title Eliminator) Oct 24 1931 Llanelly Working Men's Club Bob Fielding (Wrexham) WPTS(15) Gwyn Thomas (Llanelly) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title Eliminator) Dec 2 1931 Wrexham Drill Hall Bob Fielding (Wrexham) WRTD8(15) Cliff Peregrine (Ammanford) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title Final Eliminator) Feb 6 1932 Merthyr Labour Stadium Bob Fielding (Wrexham) WPTS(15) Freddy Morgan (Gilfach Goch) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title) Nov 26 1932 Llanelly Working Men's Club Jimmy Jones (Pontypridd) WPTS(15) Bobby Morgan (Abertridwr) (Welsh Area Flyweight Title Eliminator) Dec 3 1932 Llanelly Working Men's Club Kid Hughes