A BLANK SLATE? Brain Science and Cultures Florence, April 4Nd - 6Th 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Sophon Shadraconis Claremont Graduate University, [email protected]

LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 15 2013 Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Sophon Shadraconis Claremont Graduate University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux Part of the Business Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Shadraconis, Sophon (2013) "Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes," LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 15. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux/vol3/iss1/15 Shadraconis: Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Shadraconis 1 Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Sophon Shadraconis Claremont Graduate University Abstract This paper explores the salience of archetypes through modern day idealization of leaders as heroes. The body of research in evolutionary psychology and ethology provide support for archetypal theory and the influence of archetypes (Hart & Brady, 2005; Maloney, 1999). Our idealized self is reflected in archetypes and it is possible that we draw on archetypal themes to compensate for a reduction in meaning in our modern day work life. Archetypal priming can touch a person’s true self and result in increased meaning in life. According to Faber and Mayer (2009), drawing from Jung (1968), an archetype is an, “internal mental model of a typical, generic story character to which an observer might resonate emotionally” (p. 307). Most contemporary researchers maintain that archetypal models are transmitted through culture rather than biology, as Jung originally argued (Faber & Mayer, 2009). Archetypes as mental models can be likened to image schemas, foundational mind/brain structures that are developed during human pre-verbal experience (Merchant, 2009). -

The Pandemic Exposes Human Nature: 10 Evolutionary Insights PERSPECTIVE Benjamin M

PERSPECTIVE The pandemic exposes human nature: 10 evolutionary insights PERSPECTIVE Benjamin M. Seitza,1, Athena Aktipisb, David M. Bussc, Joe Alcockd, Paul Bloome, Michele Gelfandf, Sam Harrisg, Debra Liebermanh, Barbara N. Horowitzi,j, Steven Pinkerk, David Sloan Wilsonl, and Martie G. Haseltona,1 Edited by Michael S. Gazzaniga, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, and approved September 16, 2020 (received for review June 9, 2020) Humans and viruses have been coevolving for millennia. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19) has been particularly successful in evading our evolved defenses. The outcome has been tragic—across the globe, millions have been sickened and hundreds of thousands have died. Moreover, the quarantine has radically changed the structure of our lives, with devastating social and economic consequences that are likely to unfold for years. An evolutionary per- spective can help us understand the progression and consequences of the pandemic. Here, a diverse group of scientists, with expertise from evolutionary medicine to cultural evolution, provide insights about the pandemic and its aftermath. At the most granular level, we consider how viruses might affect social behavior, and how quarantine, ironically, could make us susceptible to other maladies, due to a lack of microbial exposure. At the psychological level, we describe the ways in which the pandemic can affect mating behavior, cooperation (or the lack thereof), and gender norms, and how we can use disgust to better activate native “behavioral immunity” to combat disease spread. At the cultural level, we describe shifting cultural norms and how we might harness them to better combat disease and the negative social consequences of the pandemic. -

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

Epa 542-R-17-003

Oce of Land and Emergency Management EPA 542-R-17-003 Brownf ields Road Map to Understanding Options for Site Investigation and Cleanup Sixth Edition Site Reuse Design and Implement the Cleanup Assess and Select Cleanup Options Investigate the Site Assess the Site Learn the Basics www.epa.gov/brownfields/brownfields-roadmap [This page is intentonally left blank] Table of Contents Brownfields Road Map Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Follow the Brownfields Road Map ...................................................................................... 6 Learn the Basics .................................................................................................................. 9 Assess the Site ................................................................................................................... 20 Investigate the Site ........................................................................................................... 26 Assess and Select Cleanup Options ................................................................................... 36 Design and Implement the Cleanup ................................................................................. 43 Spotlights 1 Innovations in Contracting ................................................................................... 18 2 Supporting Tribal Revitalization ........................................................................... 19 -

Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea Black Heroes in the United States: the Representation of African Americans in Contemporary American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 1 - - 2 - Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea The Representation of Black Heroism in American Culture Relatore Laureando Prof.ssa Anna Scacchi Enrico Pizzolato n° matr.1102543 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 - 4 - Table of Contents: Preface Chapter One: The Western Victimization of African Americans during and after Slavery 1.1 – Visual Culture in Propaganda 1.2 - African Americans as Victims of the System of Slavery 1.3 - The Gift of Freedom 1.4 - The Influence of White Stereotypes on the Perception of Blacks 1.5 - Racial Discrimination in Criminal Justice 1.6 - Conclusion Chapter Two: Black Heroism in Modern American Cinema 2.1 – Representing Racial Agency Through Passive Characters 2.2 - Django Unchained: The Frontier Hero in Black Cinema 2.3 - Character Development in Django Unchained 2.4 - The White Savior Narrative in Hollywood's Cinema 2.5 - The Depiction of Black Agency in Hollywood's Cinema 2.6 - Conclusion Chapter Three: The Different Interpretations -

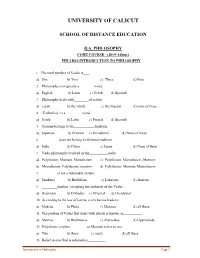

Introduction to Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system. -

23 0Ttobre 2020 Il Nuovo Presidente Nazionale È Ricevuto Dal Capo Di Stato

Marina id’I talia “Una volta marinaio... marinaio per sempre” MENSILE DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE NAZIONALE MARINAI D’ITALIA Anno LXIV n. 10/11 • 2020 Ottobre/Novembre Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. 1 comma 1 - DCB Roma 23 0ttobre 2020 Il nuovo Presidente Nazionale è ricevuto dal Capo di Stato Maggiore della Marina Militare nel giorno del suo insediamento Editoriale del Presidente Nazionale Aeronavali, presso il 3° Reparto Pianificazione Generale dello Stato Maggiore della Marina. Dall ’ottobre 1999 all’ottobre 2000 ha comandato il Caccia - torpedi niere Francesco Mimbelli . Dall ’ottobre 2000 all ’agosto 2003 ha svolto l’incarico di Capo del 2° Ufficio del 4° Reparto dello Stato Maggiore della Marina, denominato successivamente 4° Reparto o assunto da pochi giorni il prestigioso incarico alla base della nostra Marina e gli obiettivi da consegui - “Supporto al Personale ” di Mariugp. di Presidente Nazionale della nostra Associa - re. Durante il mio periodo in servizio attivo è stata la mia Dal settembre 2003 all’ottobre 2006 presso l’Ufficio Im - H zione ed è la prima volta che, in tale veste, mi ri - stella polare e intendo seguirla anche nell’espletamen - piego Ufficiali di Mariugp ha svolto l’incarico di Capo del 2° volgo a tutti Voi. Desidero, a premessa, inviare un affet - to di questo nuovo incarico. Reparto . tuoso e sincero saluto ai Marinai e ai Soci, alle Patrones - Il primo inciso descrive proprio una delle caratteristiche Dal novembre 2006 al giugno 2009 ha svolto l’incarico di se e alle relative famiglie. -

Phylogenetic Signal in Phonotactics

Phylogenetic signal in phonotactics Jayden L. Macklin-Cordes,1 Claire Bowern2 and Erich R. Round1,3,4 1 The University of Queensland | 2 Yale University | 3 University of Surrey | 4 Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History Phylogenetic methods have broad potential in linguistics beyond tree infer- ence. Here, we show how a phylogenetic approach opens the possibility of gaining historical insights from entirely new kinds of linguistic data – in this instance, statistical phonotactics. We extract phonotactic data from 112 Pama-Nyungan vocabularies and apply tests for phylogenetic signal, quanti- fying the degree to which the data reflect phylogenetic history. We test three datasets: (1) binary variables recording the presence or absence of biphones (two-segment sequences) in a lexicon (2) frequencies of transitions between segments, and (3) frequencies of transitions between natural sound classes. Australian languages have been characterized as having a high degree of phonotactic homogeneity. Nevertheless, we detect phylogenetic signal in all datasets. Phylogenetic signal is greater in finer-grained frequency data than in binary data, and greatest in natural-class-based data. These results demonstrate the viability of employing a new source of readily extractable data in historical and comparative linguistics. Keywords: historical signal, phylogenetic comparative methods, historical linguistics, phonology, comparative linguistics, linguistic phylogenetics, Pama-Nyungan, Australian languages 1. Introduction A defining methodological -

Studia Culturologica Series

volume 22, autumn-winter 2005 studia culturologica series GEORGE GALE OSWALD SCHWEMMER DIETER MERSCH HELGE JORDHEIM JAN RADLER JEAN-MARC T~TAZ DIMITRI GINEV ROLAND BENEDIKTER Maison des Sciences de I'Homme et de la Societe George Gcrle LEIBNIZ, PETER THE GREAT, AND TIIE MOUERNIZAIION OF RUSSIA or Adventures of a Philosopher-King in the East Leibniz was the modern world's lirst Universal C'itizen. Ilespite being based in a backwater northern German principalit). Leibniz' scliolarly and diploniatic missions took liim - sometimes for extendud stays -- everywhere i~nportant:to Paris and Lotidon, to Berlin, to Vien~~nand Konie. And this in a time when travel \vas anything birt easy. Leibniz' intelluctual scope was ecli~ally\vide: his philosophic focus extended all the way ti-om Locke's England to Confi~cius'C'hina, even while his geopolitical interests encom- passed all tlie vast territory from Cairo to Moscow. In short, Leibniz' acti- vities, interests and attention were not in the least hounded by tlie narrow compass of his home base. Our interests, however, must be bounded: to this end, our concern in what follows will Iiniil itself to Leibniz' relations with tlie East, tlie lands beyond the Elbe, the Slavic lands. Not only are these relations topics of intrinsic interest, they have not received anywhere near tlie attention they deserve. Our focus will be the activities of Leibniz himself, the works of the living philosopher, diplomat, and statesman, as he carried them out in his own time. Althoi~ghLeibniz' heritage continues unto today in the form of a pl~ilosophicaltradition, exa~ninationoftliis aspect of Leibnizian influ- ence nli~stawait another day. -

Final Draft Jury

Freedom in Conflict On Kant’s Critique of Medical Reason Jonas Gerlings Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 24 February 2017. European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Freedom in Conflict On Kant’s Critique of Medical Reason Jonas Gerlings Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Dr. Martin van Gelderen, EUI, Lichtenberg-Kolleg – The Göttingen Institute for Advanced Study (Supervisor) Dr. Dr. h.c. Hans Erich Bödeker, Lichtenberg-Kolleg – The Göttingen Institute for Advanced Study Prof. Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Senior Lecturer, Dr. Avi Lifschitz, UCL © Jonas Gerlings, 2016 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Jonas Gerlings certify that I am the author of the work Freedom in Conflict – Kant’s Critique of Medical Reason I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297).