THANKSGIVING DAY the American Calendar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Countherhistory Barbara Joan Zeitz, M.A. November 2017 Sarah's

CountHerhistory Barbara Joan Zeitz, M.A. November 2017 Sarah’s Thanksgiving Holiday The first proclamation for a day of thanksgiving was issued by George Washington in 1789 calling upon all Americans to express their gratitude for the successful conclusion to the war of independence and the successful ratification of the U.S. Constitution. John Adams and James Madison designated days of thanks during their presidencies and days of thanksgiving were celebrated by individual colonies and states in varying ways, on varying days the next thirty-eight years, until a woman came along. Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879) magazine mogul of her day who has been likened to "Anna Wintour of our day,” was a poet, author, editor, literally the first female to edit a magazine. In the mid-nineteenth century, Hale was one of the most influential women in America and shaped most of the personal attitudes and thoughts held by women. Not only a publicist for women’s education, women’s property rights and professions for women, Hale advocated for early childhood education, public health laws and other progressive community-minded causes. She was an expert of aesthetic judgment in fashion, literature, architecture, and civic policies. Progressive causes such as creating a national holiday to celebrate thanksgiving between Native Americans and immigrant Pilgrims, came natural to Hale. She founded the Seaman’s Aid Society in 1833 to assist the surviving families of Boston sailors who died at sea. And in 1851 founded the Ladies’ Medical Missionary Society of Philadelphia, which fought for a woman’s right to travel abroad as a medical missionary without the accompaniment of a man. -

Into the Breach Video Series Study Guide

Into the Breach Video Series Study Guide Faith in Action Faith Into the Breach Video Series Study Guide Copyright © Knights of Columbus, 2021. All rights reserved. Quotations from Into the Breach, An Apostolic Exhortation to Catholic Men, Copyright © 2015, are used with permission of Diocese of Phoenix. Quotations from New American Bible, Revised Edition, Copyright © 2010, are used with permission of Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., Washington, DC. Quotations from Catholic Word Book #371, Copyright © 2007, are used with permission of Knights of Columbus Supreme Council and Our Sunday Visitor, Huntington, IN 46750. Cover photograph credit: Shutterstock. Russo, Alex. Saint Michael Archangel statue on the top of Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome, Italy, used with permission. Getty Images. Trood, David. Trekking in the Austrian Alps, used with permission. No part of this booklet may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS Introduction. 1 A Man Who Can Stand in the Breach. 2 How to Use This Study Guide . 3 How to Lead a Small Group Session . 8 INTO THE BREACH EPISODES Masculinity . 12 Brotherhood. 19 Leadership . 27 Fatherhood. 35 Family . 42 Life . 49 Prayer . 56 Suffering . 64 Sacramental Life . 72 Spiritual Warfare . 80 Evangelization . 87 The Cornerstone . 95 APPENDIX Definitions . 103 Catholic Information Service. 107 Faith in Action . 108 INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS Introduction “And I sought for a man among them who should build up the wall and stand in the breach before me for the land…” (Ezekiel 22:30) In 2015, Bishop Thomas J. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Thanksgiving from Smith's Restaurant Is Back

Thanksgiving from Smith's Rest urant is back Cohoes landmark now offers holiday dinner to go For many years, it was a tra remain the way people remem becoming Smith's full-time 1 p.m. on Thanksgiving Day. dining room, where the big dition for Cohoes.area families bered it, with distinctive fea chef. He gives Smith's Something new at Smith's working fireplace gives every to enjoy Thanksgiving dinner tures like Big Mike's 50-foot Thanksgiving-to-go package starting this month is the intro event a festive flavor at this prepared at Smith's Restaurant, long mahogany bar and the the traditional flavor families duction of live music in the time of year. the historic dining spot at 171 Political Booth where the origi-. crave at this time of year. restaurant's spacious dining The new Smith's team envi Remsen st. in the heart of the nal Smith held court. Smith's Thanksgiving pack room. After hosting their first sions the restaurant as a com city's Historic District. This At the same time, there -have age allows you to feed as many show last weekend, Smith's fortable place for adults to dine year, the new management of been updates like the flat people as you want for $15 per welcomes Tommy Decelle's and spend time together, where Smith's is bringing that tradi screen TVs behind the bar and person. It consists of sliced Route 66 for a pre you can eat filet mignon at the tion back with a twist, offering the addition of draught beer. -

Clarence School News

CLARENCE CENTRAL SCHOOL DISTRICT NEWSLETTER • GRADUATION ISSUE • JULY 2020 Clarence School News Clarence Center • Harris Hill • Ledgeview • Sheridan Hill • Clarence Middle School • Clarence High School Congratulations to the Class of 2020 Additional Profiles of Top Students appear on pgs. 2-5 Valedictorian Salutatorian GRANT GIANGRASSO RYAN LOPEZ Son of Mary Ellen Gianturco and James Grasso Son of John and Pam Lopez Activities: Chrysalis Literary Magazine (Editor-In- Activities: Senior Class Treasurer; The University at Chief ), Boy Scout Troop 27 (Senior Patrol Leader), Buffalo Gifted Math Program; Science Olympiad Wind Ensemble (Trumpet Section Leader), Jazz – President, Treasurer; Scholastic Bowl President Band, Model United Nations (President), Altar (4 yrs); Member – Student Council; Cross Server at Nativity Church, University at Buffalo Country; Outdoor Track; Travel Soccer; Ski Club; Gifted Math Program (Ambassador), Roswell Symphonic Band; Wind Ensemble. Park Summer Research Internship, Superintendent’s Advisory Group, National Volunteer Services: CHS Winter Sleepout (4 yrs); Member – Clarence Youth Honor Society, Science Olympiad (Vice President), Men’s Swim Team, Lifeguard, Bureau; Bald for Bucks participant; Vacation Bible School Counselor; Clarence SCUBA, Sailing. Marching Band; Student Guide for New Teacher Information Day. Volunteer Services: Eagle Scout Project (Audio/Visual Tour at Reinstein Honors: Salutatorian, Graduate of The University at Buffalo Gifted Math Woods), Buffalo General Hospital, St. Joseph’s Hospital, -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

Thanksgiving Thanksgiving Day Is a Holiday Celebrated Each Year in the United States

World Book Kids Database ® World Book Online: The trusted, student-friendly online reference tool. Name: _______________________________________________________ Date:__________________ Thanksgiving Thanksgiving Day is a holiday celebrated each year in the United States. What do you know about the history of this holiday? Use this webquest to learn more about Thanksgiving’s history and how the holiday is celebrated. While Thanksgiving Day is celebrated in both the United States and Canada (on a different date), this webquest will focus on Thanksgiving in the United States. First, log onto www.worldbookonline.com Then, click on “Kids.” If prompted, log on with ID and password Find It! Find the answers to the questions below by using the “search” tool to search key words. Since this activity is about Thanksgiving Day, you can start by searching the key words “Thanksgiving Day.” Since we are focusing on Thanksgiving in the United States, please use the “Thanksgiving Day (United States)” article. Write the answers below each question. 1. When is Thanksgiving Day celebrated in the United States? 2. What do people give thanks for on Thanksgiving Day? 3. Who is the woman who worked hard to make Thanksgiving Day a national holiday? 4. In 1863, which president made the last Thursday in November a national day of thanksgiving? 5. Congress made Thanksgiving Day a legal national holiday beginning in _______________. 6. Name five things to eat that are usually included in a Thanksgiving dinner. © 2017 World Book, Inc. Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. All rights reserved. World Book and the globe device are trademarks or registered trademarks of World Book, Inc. -

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

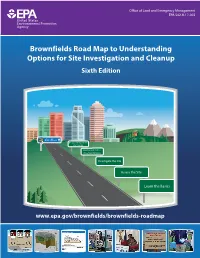

Epa 542-R-17-003

Oce of Land and Emergency Management EPA 542-R-17-003 Brownf ields Road Map to Understanding Options for Site Investigation and Cleanup Sixth Edition Site Reuse Design and Implement the Cleanup Assess and Select Cleanup Options Investigate the Site Assess the Site Learn the Basics www.epa.gov/brownfields/brownfields-roadmap [This page is intentonally left blank] Table of Contents Brownfields Road Map Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Follow the Brownfields Road Map ...................................................................................... 6 Learn the Basics .................................................................................................................. 9 Assess the Site ................................................................................................................... 20 Investigate the Site ........................................................................................................... 26 Assess and Select Cleanup Options ................................................................................... 36 Design and Implement the Cleanup ................................................................................. 43 Spotlights 1 Innovations in Contracting ................................................................................... 18 2 Supporting Tribal Revitalization ........................................................................... 19 -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7.