Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, Long Plain First Nation, Swan Lake First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Since 1985, Stars Has Flown More Than 45,000 Missions Across Western Canada

2019/20 Missions SINCE 1985, STARS HAS FLOWN MORE THAN 45,000 MISSIONS ACROSS WESTERN CANADA. Below are 760 STARS missions carried out during 2019/20 from our base in Winnipeg. MANITOBA 760 Alonsa 2 Altona 14 Amaranth 2 Anola 2 Arborg 4 Ashern 15 Austin 2 Bacon Ridge 2 Balsam Harbour 1 Beausejour 14 Benito 1 Beulah 1 Birds Hill 2 Black River First Nation 2 Bloodvein First Nation 6 Blumenort 1 Boissevain 3 Bowsman 1 Brandon 16 Brereton Lake 3 Brokenhead Ojibway Nation 1 Brunkild 2 Caddy Lake 1 Carberry 1 Carman 4 Cartwright 1 Clandeboye 1 Cracknell 1 Crane River 1 Crystal City 6 Dacotah 3 Dakota Plains First Nation 1 Dauphin 23 Dog Creek 4 Douglas 1 Dufresne 2 East Selkirk 1 Ebb and Flow First Nation 2 Edrans 1 Elphinstone 1 Eriksdale 9 Fairford 2 Falcon Lake 1 Fannystelle 1 Fisher Branch 1 Fisher River Cree Nation 4 Fort Alexander 3 Fortier 1 Foxwarren 1 Fraserwood 2 Garson 1 Gilbert Plains 1 Gimli 15 Giroux 1 Gladstone 1 Glenboro 2 Grand Marais 2 Grandview 1 Grosse Isle 1 Grunthal 5 Gypsumville 3 Hadashville 3 Hartney 1 Hazelridge 1 Headingley 5 Hilbre 1 Hodgson 21 Hollow Water First Nation 3 Ile des Chênes 3 Jackhead 1 Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation 1 Kelwood 1 Kenton 1 Killarney 8 Kirkness 1 Kleefeld 1 La Rivière 1 La Salle 1 Lac du Bonnet 3 Landmark 3 Langruth 1 Lenore 1 Libau 1 Little Grand Rapids 3 Little Saskatchewan First Nation 7 Lockport 2 Long Plain First Nation 5 Lorette 3 Lowe Farm 1 Lundar 3 MacGregor 1 Manigotagan 2 Manitou 3 Marchand 2 Mariapolis 1 McCreary 1 Middlebro 5 Milner Ridge 2 Minnedosa 4 Minto 1 Mitchell -

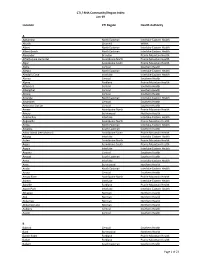

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Market Housing Program

Achieving the Right Balance CANDO’s 24th Annual Conference – October 23, 2017 Fredericton, New Brunswick 1 The Fund’s Vision Every First Nation family has the opportunity to have a home on their own land in a strong community. 2 ©2008 FNMHF 3 ©2008 FNMHF # of First Nation Applications Received by the Fund / Total # of FNs in each Prov./ Territories (as of September 30, 2017) 9/14 2/33 84/202 18/47 16/63 13/75 13/40 65/134 12/35 ©2008 FNMHF First Nations announced for Credit Enhancement as of October 5, 2017 • Miawpukek, NF •Siksika, AB •Neskonlith, BC •Penelakut, BC • Membertou, NS • T’it’q’et, BC • Nipissing, ON • Nooaitch, BC • Lac La Ronge, SK • Eastmain, QC • Mississauga, ON • Skeetchestn, BC • Batchewana, ON • Tsawout, BC • Wemindji, QC • Kwanlin Dün, YT • Onion Lake, SK • Sagamok, ON • Henvey Inlet, ON • Sechelt, BC • Atikameksheng, ON • Seabird Island, BC • Beausoleil, ON •Teslin Tlingit Council, YT Anishnawbek, ON • Tk’emlups, BC • Wahnapitae, ON • Tsartlip First Nation, BC • Whitefish River, ON • Moose Cree, ON • Temagami, ON • Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in, YT • Champagne & • Serpent River, ON • Carcross/Tagish, YT Aishihik, YT • Curve Lake, ON • Penticton, BC • Skidegate, BC • Pic River, ON • Mohawks of the Bay • Aundeck Omni • Quatsino, BC • Lac Seul, ON of Quinte, ON Kaning, ON • Little Shuswap ,BC • Waswanipi, QC • Adams Lake, BC • Long Plain, MB • Mistissini, QC • Flying Dust, SK • Garden River, ON • Skwah, BC •Saugeen, ON • Okanagan, BC • Lower Nicola, BC • Fisher River, MB •Wahta, ON • Chisasibi, QC • Upper Nicola, BC •Alderville, ON •Mattagami, ON • Chippewas of • Hiawatha, ON • Lake Cowichan, BC •Chapleau Cree, ON Nawash, ON • M’Chigeeng, ON •Leq’á:mél, BC •Nuxalk, BC • Simpcw, BC • ʔaq'am (St. -

Page 1 of 3 MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS POLICE SERVICE

MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS POLICE SERVICE (DAKOTA OJIBWAY POLICE SERVICE) History The original establishment of the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council Police Department, now known as the Dakota Ojibway Police Service, dated December 1974, was prepared and agreed to by all Chiefs of the D.O.T.C. After three years of negotiations, funding was approved by the different levels of government. In November of 1977, the police department commenced operations with one Chief of Police and nine members. The program was funded by Indian & Northern Affairs Canada from 1977 to 1993. The development of the Police Service was to establish local control and accountability to the First Nation communities. In November of 1993, the Police Service ceased operations due to a lack of funding commitment from the Province of Manitoba. Tripartite negotiations reconvened in 1994 and technical meetings took place as follows: March 10, May 12, May 26 and June 23, 1994. On May 19, 1994, the D.O.T.C. Council of Chiefs and representatives from both levels of Government, Manitoba Justice and Public Safety Canada were able to secure an Interim Policing Service Agreement which saw the restoration of joining policing services (D.O.P.S./R.C.M.P.) to (7) seven of the (8) eight D.O.T.C. Member First Nation communities, with the effective start date of June 1, 1994. On December 31, 1994, a long-term Tripartite Agreement was finalized and on February 1, 1995, the Dakota Ojibway Police Service resumed full-time policing services to (6) six D.O.T.C. First Nation communities: Birdtail Sioux First Nation, Dakota Plains Wahpeton Nation, Long Plain First Nation, Canupawakpa Dakota Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation and Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. -

Comparative Indicators of Population Health and Health Care Use for Manitoba’S Regional Health Authorities

Comparative Indicators of Population Health and Health Care Use for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities A POPULIS Project June 1999 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Charlyn Black, MD, ScD Noralou P Roos, PhD Randy Fransoo, MSc Patricia Martens, PhD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals whose efforts and expertise made it possible to produce this report, especially Jan Roberts and Carolyn DeCoster for their consultations and advice throughout the project. We also wish to express our appreciation to the many individuals who provided feedback on draft versions, including John Millar and Fred Toll, and those who provided insights into the data interpretation, including Donna Turner and Bob Tate. Because of the extensive nature of this report, we gratefully acknowledge many persons for their technical support: Shelley Derksen, David Friesen, Pat Nicol, Dawn Traverse, Bogdan Bogdanovic, Charles Burchill, Leonard MacWilliam, Sandra Peterson, Carmen Steinbach, Randy Walld, and Erin Minish. Thanks to Carole Ouelette for final preparation of this document. We are indebted to the Manitoba Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation, Health Information Services (Manitoba Health) and the Office of Vital Statistics in the Agency of Consumer and Corporate Affairs for providing data. The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health was intended or should be implied. This report was prepared at the request of Manitoba Health as part of the contract between the University of Manitoba and Manitoba Health. Tutorial Readers who would like to proceed directly to the section that describes how one might apply the information found in this document are encouraged to go directly to section 4: Interpreting the Data for Local Use, on page 20. -

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

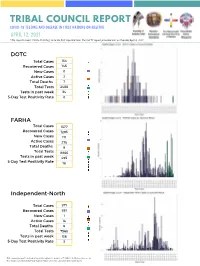

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Line 3 and Prairie Region News for Indigenous Nations, Governments and Groups

Volume 3, June 2021 Line 3 and Prairie Region News For Indigenous Nations, governments and groups A message from Enbridge Truth is the first step toward reconciliation The recent confirmation of a burial site and injustices Indigenous of the graves of 215 Indigenous children peoples have endured in Kamloops is a tragic reminder of throughout history and that Canada’s residential school system that continue today. must be acknowledged and should never be forgotten. Healing our communities and our country is going to take Our hearts go out to Indigenous peoples time, and the only way we can across Canada, including the families of the overcome the damage of the missing children and their communities, the past and heal our communities survivors and inter-generational survivors and our country is by focusing of residential schools. We cannot begin to on truth and reconciliation. imagine the depth of sorrow and suffering your communities are feeling. Without hesitation, Enbridge joins in the call for the Of course, this is so much bigger than the expedient release of official This June 21, as Canadians again prepare Kamloops school alone. Across Canada, records and documents that may shed to mark the rich culture of Indigenous there were 139 residential schools, additional light on the victims of residential peoples on National Indigenous Peoples’ including many on the Prairies. schools. And we will be engaging Day, let us all reflect on how we, as communities to see how we can best individuals, can make a difference and This devastating news has brought again provide support in this time of need. -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

Annual Report 2018-2019

2018-2019 Annual Report 2 Table of Contents Advocate's Message ................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ................................................................. 14 Annual Report Theme: The 30th Anniversary of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child ........................... 19 Overview of Initiatives and Activities ..................................... 22 Community Outreach Across Manitoba .................................. 29 Special Reports and Recommendations for Change .............. 32 Advocacy Services Program ..................................................... 38 Investigations and Child Death Reviews ................................ 47 Quality Assurance .................................................................... 53 Research Hub ............................................................................ 55 Youth Engagement ................................................................... 59 2019-2020 Service Plan ............................................................ 63 3 This fall marks the 30th anniversary of the UNCRC. As such, this is a good opportunity for all Canadians to learn more about the UNCRC, to think about how rights are important to young people in our country, and understand in what ways these rights are recognized – or not recognized – in the lives of all children and youth here in Manitoba and across Canada. The UNCRC describes more than 40 specific human rights for young people. These include rights about the things young -

C O M M U N I Q U É

c o m m u n i q u é POUR DIFFUSION IMMÉDIATE Le 23 septembre 2011 Le vote par anticipation commence demain Il y a plus d’occasions de voter par anticipation que jamais auparavant Grâce au nombre accru de centres de scrutin et à une journée additionnelle pour le scrutin par anticipation, il est plus facile que jamais pour les Manitobains et Manitobaines d’exercer leur droit démocratique. Le jour du scrutin au Manitoba est le mardi 4 octobre, mais les Manitobains et Manitobaines peuvent voter par anticipation à partir de demain (le 24 septembre) jusqu’au samedi 1er octobre, une journée de plus qu’aux élections précédentes. Il y a environ 300 centres de scrutin par anticipation dans la province, y compris dans tous les bureaux du directeur du scrutin, ainsi que dans d’autres endroits pratiques comme des centres commerciaux, des campus universitaires et l’aéroport de Winnipeg. Les électeurs admissibles peuvent voter à n’importe quel centre de scrutin par anticipation sans devoir présenter d’explications. Pour être admissible à voter, il faut : • être citoyen canadien; • avoir au moins 18 ans le jour du scrutin; • avoir résidé au Manitoba pendant au moins six mois immédiatement avant le jour du scrutin. Les électeurs doivent présenter une pièce d’identité avec photo délivrée par le gouvernement (ex., un permis de conduire) ou deux autres documents portant leur nom. Il sera également utile d’apporter sa fiche de recensement. Les centres de scrutin par anticipation sont ouverts de 8 h à 20 h tous les jours, sauf le dimanche où ils sont ouverts de 12 h à 18 h.