Brokenhead First Nation V. Canada (Attorney General)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Needs Assessment

NEEDS ASSESSMENT 105-1555 St. James Street p. (204) 946-1869 [email protected] Winnipeg, Manitoba f. (204) 946-1871 www.scoinc.mb.ca R3H1B5 2 Table of Contents Southern Chiefs’ Organization Mandate and Member First Nations………………………….3 Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………5 Background………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Needs Assessment Goal and Objectives…………………………………………………………..7 A Socio-Ecological Approach to Violence Prevention………………………………………….8 A Brief Socio-Ecological Analysis of Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls…..11 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………………13 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………………....22 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………….…43 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………..…….46 References………………………………………..…………………………………………………….47 Appendix A: Data Collection Tools……………………………………………...…………………51 Appendix B: Partners………………………………………………………...………………………..67 Authors: Tessa Jourdain, Master of Public Health (Health Promotion) Candidate, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto Shauna Fontaine, Violence Prevention and Safety Coordinator, Southern Chiefs’ Organization 3 Southern Chiefs’ Organization Mandate Established in 1998, the Mandate of the Southern Chiefs Organization (SCO) is to protect, preserve, promote and enhance First Nation peoples’ inherent rights, languages, customs and traditions through the application and implementation of the spirit and intent -

Since 1985, Stars Has Flown More Than 45,000 Missions Across Western Canada

2019/20 Missions SINCE 1985, STARS HAS FLOWN MORE THAN 45,000 MISSIONS ACROSS WESTERN CANADA. Below are 760 STARS missions carried out during 2019/20 from our base in Winnipeg. MANITOBA 760 Alonsa 2 Altona 14 Amaranth 2 Anola 2 Arborg 4 Ashern 15 Austin 2 Bacon Ridge 2 Balsam Harbour 1 Beausejour 14 Benito 1 Beulah 1 Birds Hill 2 Black River First Nation 2 Bloodvein First Nation 6 Blumenort 1 Boissevain 3 Bowsman 1 Brandon 16 Brereton Lake 3 Brokenhead Ojibway Nation 1 Brunkild 2 Caddy Lake 1 Carberry 1 Carman 4 Cartwright 1 Clandeboye 1 Cracknell 1 Crane River 1 Crystal City 6 Dacotah 3 Dakota Plains First Nation 1 Dauphin 23 Dog Creek 4 Douglas 1 Dufresne 2 East Selkirk 1 Ebb and Flow First Nation 2 Edrans 1 Elphinstone 1 Eriksdale 9 Fairford 2 Falcon Lake 1 Fannystelle 1 Fisher Branch 1 Fisher River Cree Nation 4 Fort Alexander 3 Fortier 1 Foxwarren 1 Fraserwood 2 Garson 1 Gilbert Plains 1 Gimli 15 Giroux 1 Gladstone 1 Glenboro 2 Grand Marais 2 Grandview 1 Grosse Isle 1 Grunthal 5 Gypsumville 3 Hadashville 3 Hartney 1 Hazelridge 1 Headingley 5 Hilbre 1 Hodgson 21 Hollow Water First Nation 3 Ile des Chênes 3 Jackhead 1 Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation 1 Kelwood 1 Kenton 1 Killarney 8 Kirkness 1 Kleefeld 1 La Rivière 1 La Salle 1 Lac du Bonnet 3 Landmark 3 Langruth 1 Lenore 1 Libau 1 Little Grand Rapids 3 Little Saskatchewan First Nation 7 Lockport 2 Long Plain First Nation 5 Lorette 3 Lowe Farm 1 Lundar 3 MacGregor 1 Manigotagan 2 Manitou 3 Marchand 2 Mariapolis 1 McCreary 1 Middlebro 5 Milner Ridge 2 Minnedosa 4 Minto 1 Mitchell -

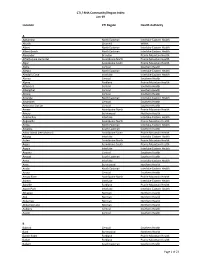

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks©

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks© by Brenda Elias John D. O’Neil Annalee Yassi Benita Cohen Department of Community Health Sciences University of Manitoba For additional copies of this report please contact CAHR office at 204-789-3250 April 1997 SAGKEENG FIRST NATION: DEVELOPMENT IMPACTS AND THE PERCEPTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH RISKS FINAL REPORT BRENDA ELIAS JOHN O’NEIL ANNALEE YASSI BENITA COHEN University of Manitoba Northern Health Research Unit Occupational and Environmental Health Unit Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine (c) April 1997 Funding provided by the National Health Research and Development Program NHRDP Project No. 6607-1620-63 1 1.0 Introduction In 1988, a critical assessment was conducted on how governments and industry address potential health impacts of industrial developments in northern regions of Canada. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Research Council (CEARC) held several regional workshops across Canada to foster discussion on northern and Aboriginal understandings of environmental health issues. Many broad recommendations emerged: ∗ the health of a community should be understood before a development project is underway; ∗ the impacts of an existing industrial site on a community over time should be understood by actually studying whether there is industry-related diseases (such as cancer or lung problems) developing in that community; ∗ a communication approach that provides scientific information on contaminants to northern communities should be developed; ∗ a constructive and respectful way of understanding what northerners consider to be a danger to their health should be developed. This study is a critical response to these recommendations. It examines the cultural basis of risk perception and the importance of local knowledge in changing the assessment and management of health risks. -

Resolutions Update Report for 2012 Aga Resolutions

ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS RESOLUTIONS UPDATE REPORT FOR 2012 AGA RESOLUTIONS Chief Garrison Settee, 1 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Chief Perry Bellegarde, Pimicikamak Okimawin, Women and Girls, 2012 Cross Lake, MB Little Black Bear First Nation, SK THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED that the Chiefs-in-Assembly: 1. Make a personal and public declaration to take full responsibility to be violence free and commit to taking all actions available to them to uphold and ensure the rights of Indigenous women and girls. 2. Affirm: a. that further to Resolution 61/2010, the AFN call upon Canada to jointly establish an independent, public commission into missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. b. that further to Resolution 02/2011, the AFN call upon Canada to convene a Royal Commission on Violence against Indigenous Girls and Women to make concrete and specific recommendations to end violence against Indigenous girls and women at a national level. c. the direction for the AFN to demand that the Government of Canada support community based- initiatives and national programs that seek to promote public awareness and carry out advocacy and research about violence against Indigenous women; restore funding to the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) for maintenance of a national database on missing and murdered Indigenous women; and, ensure proper facilities and services are available within communities for those whom are victims or have lost their loved ones through acts of violence. d. the direction to the AFN and the National Chief to strongly advocate for the full protection and safety of First Nations women across Canada. -

Annual Report 2009–2010

Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism Annual Report 2009–2010 His Honour the Honourable Philip S. Lee, C.M., O.M. Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba Room 235, Legislative Building Winnipeg, MB R3C 0V8 May It Please Your Honour: I have the privilege of presenting for the information of your honour the Annual Report of Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2010. Respectfully submitted, "Original Signed By Flor Marcelino" Honourable Flor Marcelino Minister of Culture, Heritage and Tourism Deputy Minister’s Office Room 112 Legislative Building Winnipeg MB R3C 0V8 T 204-945-3794 F 204-948-3102 www.manitoba.ca/chc/ Honourable Flor Marcelino Minister of Culture, Heritage and Tourism Dear Minister Marcelino: I hav e t he hon our of s ubmitting f or y our ap proval t he 200 9–2010 Annual R eport f or Mani toba C ulture, Heritage and Tourism. The department had lead responsibility for Manitoba’s participation in the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Vancouver. Staff oversaw the development, construction and operation of the award-winning Manitoba pavilion (CentrePlace) that drew 120,000 people. Manitoba’s partnership exhibit with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights generated substantial awareness for the Museum. Other Olympics initiatives s upported b y t he department i ncluded t he O lympic T orch R elay t hrough 33 c ommunities, representation of Manitoba artists in the Cultural Olympiad, Place de la Francophonie, the Manitoba Day Victory Celebration concert, and the Aboriginal Youth Gathering. In January, the year-long Man itoba Homecoming 2010 initiative was launched, inviting Man itobans and former Manitobans to celebrate all the great events, activities and attractions our province has to offer. -

Market Housing Program

Achieving the Right Balance CANDO’s 24th Annual Conference – October 23, 2017 Fredericton, New Brunswick 1 The Fund’s Vision Every First Nation family has the opportunity to have a home on their own land in a strong community. 2 ©2008 FNMHF 3 ©2008 FNMHF # of First Nation Applications Received by the Fund / Total # of FNs in each Prov./ Territories (as of September 30, 2017) 9/14 2/33 84/202 18/47 16/63 13/75 13/40 65/134 12/35 ©2008 FNMHF First Nations announced for Credit Enhancement as of October 5, 2017 • Miawpukek, NF •Siksika, AB •Neskonlith, BC •Penelakut, BC • Membertou, NS • T’it’q’et, BC • Nipissing, ON • Nooaitch, BC • Lac La Ronge, SK • Eastmain, QC • Mississauga, ON • Skeetchestn, BC • Batchewana, ON • Tsawout, BC • Wemindji, QC • Kwanlin Dün, YT • Onion Lake, SK • Sagamok, ON • Henvey Inlet, ON • Sechelt, BC • Atikameksheng, ON • Seabird Island, BC • Beausoleil, ON •Teslin Tlingit Council, YT Anishnawbek, ON • Tk’emlups, BC • Wahnapitae, ON • Tsartlip First Nation, BC • Whitefish River, ON • Moose Cree, ON • Temagami, ON • Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in, YT • Champagne & • Serpent River, ON • Carcross/Tagish, YT Aishihik, YT • Curve Lake, ON • Penticton, BC • Skidegate, BC • Pic River, ON • Mohawks of the Bay • Aundeck Omni • Quatsino, BC • Lac Seul, ON of Quinte, ON Kaning, ON • Little Shuswap ,BC • Waswanipi, QC • Adams Lake, BC • Long Plain, MB • Mistissini, QC • Flying Dust, SK • Garden River, ON • Skwah, BC •Saugeen, ON • Okanagan, BC • Lower Nicola, BC • Fisher River, MB •Wahta, ON • Chisasibi, QC • Upper Nicola, BC •Alderville, ON •Mattagami, ON • Chippewas of • Hiawatha, ON • Lake Cowichan, BC •Chapleau Cree, ON Nawash, ON • M’Chigeeng, ON •Leq’á:mél, BC •Nuxalk, BC • Simpcw, BC • ʔaq'am (St. -

Page 1 of 3 MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS POLICE SERVICE

MANITOBA FIRST NATIONS POLICE SERVICE (DAKOTA OJIBWAY POLICE SERVICE) History The original establishment of the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council Police Department, now known as the Dakota Ojibway Police Service, dated December 1974, was prepared and agreed to by all Chiefs of the D.O.T.C. After three years of negotiations, funding was approved by the different levels of government. In November of 1977, the police department commenced operations with one Chief of Police and nine members. The program was funded by Indian & Northern Affairs Canada from 1977 to 1993. The development of the Police Service was to establish local control and accountability to the First Nation communities. In November of 1993, the Police Service ceased operations due to a lack of funding commitment from the Province of Manitoba. Tripartite negotiations reconvened in 1994 and technical meetings took place as follows: March 10, May 12, May 26 and June 23, 1994. On May 19, 1994, the D.O.T.C. Council of Chiefs and representatives from both levels of Government, Manitoba Justice and Public Safety Canada were able to secure an Interim Policing Service Agreement which saw the restoration of joining policing services (D.O.P.S./R.C.M.P.) to (7) seven of the (8) eight D.O.T.C. Member First Nation communities, with the effective start date of June 1, 1994. On December 31, 1994, a long-term Tripartite Agreement was finalized and on February 1, 1995, the Dakota Ojibway Police Service resumed full-time policing services to (6) six D.O.T.C. First Nation communities: Birdtail Sioux First Nation, Dakota Plains Wahpeton Nation, Long Plain First Nation, Canupawakpa Dakota Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation and Sioux Valley Dakota Nation. -

Comparative Indicators of Population Health and Health Care Use for Manitoba’S Regional Health Authorities

Comparative Indicators of Population Health and Health Care Use for Manitoba’s Regional Health Authorities A POPULIS Project June 1999 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba Charlyn Black, MD, ScD Noralou P Roos, PhD Randy Fransoo, MSc Patricia Martens, PhD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals whose efforts and expertise made it possible to produce this report, especially Jan Roberts and Carolyn DeCoster for their consultations and advice throughout the project. We also wish to express our appreciation to the many individuals who provided feedback on draft versions, including John Millar and Fred Toll, and those who provided insights into the data interpretation, including Donna Turner and Bob Tate. Because of the extensive nature of this report, we gratefully acknowledge many persons for their technical support: Shelley Derksen, David Friesen, Pat Nicol, Dawn Traverse, Bogdan Bogdanovic, Charles Burchill, Leonard MacWilliam, Sandra Peterson, Carmen Steinbach, Randy Walld, and Erin Minish. Thanks to Carole Ouelette for final preparation of this document. We are indebted to the Manitoba Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation, Health Information Services (Manitoba Health) and the Office of Vital Statistics in the Agency of Consumer and Corporate Affairs for providing data. The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health was intended or should be implied. This report was prepared at the request of Manitoba Health as part of the contract between the University of Manitoba and Manitoba Health. Tutorial Readers who would like to proceed directly to the section that describes how one might apply the information found in this document are encouraged to go directly to section 4: Interpreting the Data for Local Use, on page 20. -

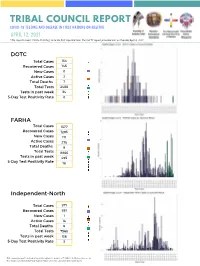

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including