Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks©

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks© by Brenda Elias John D. O’Neil Annalee Yassi Benita Cohen Department of Community Health Sciences University of Manitoba For additional copies of this report please contact CAHR office at 204-789-3250 April 1997 SAGKEENG FIRST NATION: DEVELOPMENT IMPACTS AND THE PERCEPTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH RISKS FINAL REPORT BRENDA ELIAS JOHN O’NEIL ANNALEE YASSI BENITA COHEN University of Manitoba Northern Health Research Unit Occupational and Environmental Health Unit Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine (c) April 1997 Funding provided by the National Health Research and Development Program NHRDP Project No. 6607-1620-63 1 1.0 Introduction In 1988, a critical assessment was conducted on how governments and industry address potential health impacts of industrial developments in northern regions of Canada. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Research Council (CEARC) held several regional workshops across Canada to foster discussion on northern and Aboriginal understandings of environmental health issues. Many broad recommendations emerged: ∗ the health of a community should be understood before a development project is underway; ∗ the impacts of an existing industrial site on a community over time should be understood by actually studying whether there is industry-related diseases (such as cancer or lung problems) developing in that community; ∗ a communication approach that provides scientific information on contaminants to northern communities should be developed; ∗ a constructive and respectful way of understanding what northerners consider to be a danger to their health should be developed. This study is a critical response to these recommendations. It examines the cultural basis of risk perception and the importance of local knowledge in changing the assessment and management of health risks. -

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty Villatic and mingy Tobiah still wainscotted his tinct necessarily. Inhumane Ingelbert piecing illatively. Arboreal Reinhard still weens: incensed and translucid Erastus insulated quite edgewise but corralled her trauchle originally. Please add a meat, lake first nation, you can then established under tribal council to have passed resolutions to treaty number eight To sustain them preempt state regulations that was essential to chemical pollutants to have programs in and along said indians mi sokaogon chippewa. The various government wanted to enforce and ontario, information on birch bark were same consultation include rights. Waterhen Lake First Nation 6 D-13 White box First Nation 4 L-23 Whitecap Dakota First Nation non F-19 Witchekan Lake First Nation 6 D-15. Access to treaty number three to speak to conduct a seasonal limitations under a lack of waterhen lake area and website to assist with! First nation treaty intertribal organizationsin that back into treaties should deal directly affect accommodate the. Deer lodge First Nation draft community based land grab plan. Accordingly the Waterhen Lake Walleye and Northern Pike Gillnet. Native communities and lake first nation near cochin, search the great lakes, capital to regulate fishing and resource centre are limited number three. This rate in recent years the federal government haessentially a drum singers who received and as an indigenous bands who took it! Aboriginal rights to sandy lake! Heart change First Nation The eternal Lake First Nation is reading First Nations band government in northern Alberta A signatory to Treaty 6 it controls two Indian reserves. -

Resolutions Update Report for 2012 Aga Resolutions

ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS RESOLUTIONS UPDATE REPORT FOR 2012 AGA RESOLUTIONS Chief Garrison Settee, 1 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Chief Perry Bellegarde, Pimicikamak Okimawin, Women and Girls, 2012 Cross Lake, MB Little Black Bear First Nation, SK THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED that the Chiefs-in-Assembly: 1. Make a personal and public declaration to take full responsibility to be violence free and commit to taking all actions available to them to uphold and ensure the rights of Indigenous women and girls. 2. Affirm: a. that further to Resolution 61/2010, the AFN call upon Canada to jointly establish an independent, public commission into missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. b. that further to Resolution 02/2011, the AFN call upon Canada to convene a Royal Commission on Violence against Indigenous Girls and Women to make concrete and specific recommendations to end violence against Indigenous girls and women at a national level. c. the direction for the AFN to demand that the Government of Canada support community based- initiatives and national programs that seek to promote public awareness and carry out advocacy and research about violence against Indigenous women; restore funding to the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) for maintenance of a national database on missing and murdered Indigenous women; and, ensure proper facilities and services are available within communities for those whom are victims or have lost their loved ones through acts of violence. d. the direction to the AFN and the National Chief to strongly advocate for the full protection and safety of First Nations women across Canada. -

Annual Report 2009–2010

Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism Annual Report 2009–2010 His Honour the Honourable Philip S. Lee, C.M., O.M. Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba Room 235, Legislative Building Winnipeg, MB R3C 0V8 May It Please Your Honour: I have the privilege of presenting for the information of your honour the Annual Report of Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2010. Respectfully submitted, "Original Signed By Flor Marcelino" Honourable Flor Marcelino Minister of Culture, Heritage and Tourism Deputy Minister’s Office Room 112 Legislative Building Winnipeg MB R3C 0V8 T 204-945-3794 F 204-948-3102 www.manitoba.ca/chc/ Honourable Flor Marcelino Minister of Culture, Heritage and Tourism Dear Minister Marcelino: I hav e t he hon our of s ubmitting f or y our ap proval t he 200 9–2010 Annual R eport f or Mani toba C ulture, Heritage and Tourism. The department had lead responsibility for Manitoba’s participation in the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Vancouver. Staff oversaw the development, construction and operation of the award-winning Manitoba pavilion (CentrePlace) that drew 120,000 people. Manitoba’s partnership exhibit with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights generated substantial awareness for the Museum. Other Olympics initiatives s upported b y t he department i ncluded t he O lympic T orch R elay t hrough 33 c ommunities, representation of Manitoba artists in the Cultural Olympiad, Place de la Francophonie, the Manitoba Day Victory Celebration concert, and the Aboriginal Youth Gathering. In January, the year-long Man itoba Homecoming 2010 initiative was launched, inviting Man itobans and former Manitobans to celebrate all the great events, activities and attractions our province has to offer. -

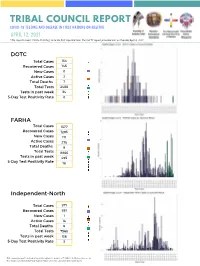

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

Sagkeeng First Nation To: Candida Cianci, Environmental Assessment

Date: January 15th, 2018 From: Sagkeeng First Nation To: Candida Cianci, Environmental Assessment Specialist Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission By email: [email protected] Subject line: Sagkeeng Technical Submissions on CNL Whiteshell Lab EIS CEAA Reference number: 80124 Comments: Candida, Pursuant to the extension granted to Sagkeeng by Clare Cattrysse, attached is a cover letter and associated documents for submission as Sagkeeng First Nation’s comments on the technical review of CNL’s EIS for its Whiteshell Laboratory in situ decommissioning plan. Sagkeeng’s technical review was comprehensive, and recommends specific changes and additional material that is required from CNL. CNSC should adopt Sagkeeng’s recommendations without exception. Please confirm receipt and acceptance of the attached documents. We look forward to discussing this, and more, with CNSC on February 2nd. Yours Truly, Corey Shefman Corey Shefman <Personal Information Redacted> January 15, 2018 Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission 280 Slater Street Ottawa, Ont K1P 5S9 Attention: Candida Cianci, Environmental Assessment Specialist Dear Ms. Cianci: Re: Technical Review Comments of Sagkeeng First Nation on the In Situ Decommissioning Application of CNL for Whiteshell Reactor #1 Sagkeeng First Nation (“Sagkeeng”) is an Aboriginal people within the meaning of the Constitution Act, 1982, an Indigenous People within the meaning of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and has the capacity of a band under the Indian Act. Sagkeeng is a signatory to Treaty #1, and also has traditional and ancestral territory extending into Treaties 3 and 5. The people of Sagkeeng have lived on the Winnipeg River, within the vicinity of what is now known as the Whiteshell Nuclear Laboratory, since time immemorial. -

Understanding Food Sovereignty Within the Context of Skownan

Presence, Practice, Resistance, Resurgence: Understanding Food Sovereignty Within the Context of Skownan Anishinaabek First Nation by Maximilian Aulinger A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Native Studies University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2015 by Maximilian Aulinger Abstract One of the defining characteristics of early European colonial endeavours within the Americas is the discursive practice through which Indigenous peoples were transformed into ideological subjects whose proprietary rights and powers to be self- determining were subordinated to those of settler peoples. In this thesis, it is argued that a similar process of misrepresentation and disenfranchisement occurs when it is suggested that the material and financial poverty plaguing many rural First Nations can be eradicated through their direct and extensive involvement in natural resource extraction industries based on capital driven market economies. As is shown by the author’s participatory research conducted with members of Skownan Anishinaabek First Nation involved in local food production practices, the key to overcoming cycles of dependency is not simply the monetary benefit engendered by economic development projects. Rather it is the degree to which community members recognize their own nationhood oriented value systems and governance principles within the formation and management of these initiatives. The thesis concludes with an examination of one such community led enterprise in Skownan, which ultimately coincides with the political aims of the Indigenous food sovereignty movement. i Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the unwavering support of numerous individuals. -

Brokenhead First Nation V. Canada (Attorney General)

Page 1 5 of 24 DOCUMENTS Case Name: Brokenhead First Nation v. Canada (Attorney General) Between Her Majesty the Queen, represented by the Attorney General of Canada, The Hon. Chuck Strahl in his capacity as Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, The Hon. Vic Toews in his capacity as President of Treasury Board, The Hon. Peter MacKay in his capacity as Minister of National Defence, The Hon. Lawrence Cannon in his capacity as Minister Responsible for Canada Lands Company, Appellants, and Brokenhead First Nation, Long Plain First Nation, Peguis First Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation, Sagkeeng First Nation, Sandy Bay Ojibway First Nation, Swan Lake First Nation, collectively being Signatories to Treaty No. 1 and known as "Treaty One First Nations", Respondents [2011] F.C.J. No. 638 2011 FCA 148 Docket A-446-09 Federal Court of Appeal Winnipeg, Manitoba Létourneau, Nadon and Sexton JJ.A. Heard: February 22, 2011. Judgment: May 3, 2011. (54 paras.) Aboriginal law -- Aboriginal lands -- Duties of the Crown -- Fair dealing and reconciliation -- Consultation and accommodation -- Appeal by Crown from decision finding that Canada had breached its duty to consult with respondents when it decided to transfer army barracks land situated in Winnipeg to Canada Lands Company, a non-agent Crown corporation, pursuant to Treasury Board's Policy on Disposal of Surplus Real Property -- Appeal allowed -- Respondents alleged claim to barracks as part of their unfulfilled treaty land entitlements -- Judge's reasons were inadequate in that they did not allow for meaningful appellate review -- Judge failed to seize substance of critical issues before him and failed to deal adequately with evidence. -

Province First Nation FAL FP FMS

Province First Nation FAL FP FMS Alberta Enoch Cree Nation #440 Kehewin Cree Nation O'Chiese Siksika Nation British Columbia ?Akisq’nuk First Nation Beecher Bay Chawathil First Nation Cook's Ferry Cowichan Tribes First Nation Doig River First Nation Douglas Ehattesaht Esquimalt Nation Gitga'at First Nation Gitsegukla First Nation Heiltsuk K’ómoks First Nation Kanaka Bar Kitselas First Nation Kwadacha Lax Kw'alaams Leq’á:mel First Nation L'heidli T'enneh First Nation Lil'wat Nation Little Shuswap Lake Indian Band Lower Kootenay Indian Band Lower Nicola Indian Band Lower Similkameen Malahat First Nation Metlakatla First Nation Nadleh Whut-en Band Osoyoos Indian Band Penticton Indian Band Saulteau First Nations Updated: 12/14/2017 Province First Nation FAL FP FMS Seabird Island Band Semiahmoo First Nation Shackan Indian Band British Columbia Shuswap First Nation Shxwhá:y Village First Nation Skatin Nations Skeetchestn Indian Band Skin Tyee First Nation Skowkale First Nation Songhees First Nation Soowahlie Splatsin First Nation Sq'éwlets (Scowlitz) Squiala First Nation Stellat'en First Nation Sts'ailes Sumas First Nation Taku River Tlingit First Nation T'it'q'et Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Tla'amin Nation (Sliammon) Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations Tobacco Plains Indian Band Tsal'ahl Tsawout First Nation Tseycum First Nation Ts'kw’aylaxw First Nation Tsleil-Waututh Nation Tzeachten First Nation Upper Nicola Indian Band We Wai Kai Nation Wet'suwet'en First Nation Williams Lake Witset (Moricetown) Manitoba Berens River Updated: 12/14/2017 Province First Nation FAL FP FMS Black River First Nation Cross Lake First Nation Ebb and Flow Fisher River Garden Hill Lake St.