Green Book of Immunisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(ACIP) General Best Guidance for Immunization

9. Special Situations Updates Major revisions to this section of the best practices guidance include the timing of intramuscular administration and the timing of clotting factor deficiency replacement. Concurrent Administration of Antimicrobial Agents and Vaccines With a few exceptions, use of an antimicrobial agent does not interfere with the effectiveness of vaccination. Antibacterial agents have no effect on inactivated, recombinant subunit, or polysaccharide vaccines or toxoids. They also have no effect on response to live, attenuated vaccines, except BCG vaccines. Antimicrobial or immunosuppressive agents may interfere with the immune response to BCG and should only be used under medical supervision (for additional information, see www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/b/bcg/bcg_pi.pdf). Antiviral drugs used for treatment or prophylaxis of influenza virus infections have no effect on the response to inactivated influenza vaccine (2). However, live, attenuated influenza vaccine should not be administered until 48 hours after cessation of therapy with antiviral influenza drugs. If feasible, to avoid possible reduction in vaccine effectiveness, antiviral medication should not be administered for 14 days after LAIV administration (2). If influenza antiviral medications are administered within 2 weeks after receipt of LAIV, the LAIV dose should be repeated 48 or more hours after the last dose of zanamavir or oseltamivir. The LAIV dose should be repeated 5 days after peramivir and 17 days after baloxavir. Alternatively, persons receiving antiviral drugs within the period 2 days before to 14 days after vaccination with LAIV may be revaccinated with another approved vaccine formulation (e.g., IIV or recombinant influenza vaccine). Antiviral drugs active against herpesviruses (e.g., acyclovir or valacyclovir) might reduce the efficacy of vaccines containing live, attenuated varicella zoster virus (i.e., Varivax and ProQuad) (3,4). -

Safety of Immunization During Pregnancy a Review of the Evidence

Safety of Immunization during Pregnancy A review of the evidence Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

Adult Vaccines

What do flu, whooping cough, measles, shingles and pneumonia have in common? 1 They’re viruses that can make you very sick. 2 Vaccines can help prevent them. Protect yourself and those you care about. Get vaccinated at a network pharmacy near you. • Ask your pharmacist which vaccines are right for you. • Find out if your pharmacist can administer the recommended vaccinations. • Many vaccinations are covered by your plan at participating retail pharmacies. • Don’t forget to present your member ID card to the pharmacist at the time of service! The following vaccines are available and can be administered by pharmacists at participating network pharmacies: • Flu (seasonal influenza) • Meningitis • Travel Vaccines (typhoid, yellow • Tetanus/Diphtheria/Pertussis • Pneumonia fever, etc.) • Hepatitis • Rabies • Childhood Vaccines (MMR, etc.) • Human Papillomavirus (HPV) • Shingles/Zoster See other side for recommended adult vaccinations. The vaccinations you need ALL adults should get vaccinated for1: • Flu, every year. It’s especially important for pregnant women, older adults and people with chronic health conditions. • Tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough). Adults should get a one-time dose of the Tdap vaccine. It’s different from the tetanus vaccine (Td), which is given every 10 years. You may need additional vaccinations depending on your age1: Young adults not yet vaccinated need: Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series (3 doses) if you are: • Female age 26 or younger • Male age 21 or younger • Male age 26 or younger who has sex with men, who is immunocompromised or who has HIV Adults born in the U.S. in 1957 or after need: Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine2 Adults should get at least one dose of MMR vaccine, unless they’ve already gotten this vaccine or have immunity to measles, mumps and rubella Adults born in the U.S. -

Vaccines You Might Need?

Do You Know Which Adult Vaccines You Might Need? Vaccines are recommended for all adults based on factors such as age, travel, occupation, medical history, and vaccines they have had in the past. Below are the main vaccines you might need. But, this list may not include every vaccine that you need. Find out which vaccines you need by taking the quiz at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/AdultQuiz/ ALL adults 19 and older, including pregnant women, need: Influenza vaccine every year • A flu vaccine is especially important for people with chronic health conditions, pregnant women, and older adults Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine (Tdap) • Adults should get a one-time dose of Tdap. Adults can get Tdap no matter when they got their last tetanus vaccine (Td), which is given every 10 years • Pregnant women should get Tdap to protect themselves and their newborn babies from whooping cough In addition to influenza and Tdap vaccines, you may also need other vaccines depending on your age or other factors. Flip the page to learn more. Talk to your healthcare provider about which vaccines are right for you. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Immunization Services Division CS235267 In addition to influenza and Tdap vaccines, you may also need other vaccines depending on your age… Young adults not yet vaccinated need: Adults born in the US in 1980 or after need: Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series Varicella “chickenpox” vaccine* (3 doses) if you are: • Adults should get 2 doses of chickenpox vaccine • -

An Insight Into the Immunization Coverage for Combined Vaccines in Albania

European Scientific Journal January 2017 edition vol.13, No.3 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 An Insight into the Immunization Coverage for Combined Vaccines in Albania Eftiola Pojani, PhD Student Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences Catholic University “Our Lady of Good Counsel” Tirana, Albania Erida Nelaj, PhD Department of Epidemiology and Infectious Disease Control Institute of Public Health, Tirana, Albania Alban Ylli, Associate Prof. University of Medicine, Faculty of Public Health, Tirana, Albania doi: 10.19044/esj.2016.v13n3p33 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v13n3p33 Abstract We aim to Provide facts about the vaccination coverage for combined vaccines such as MMR (Measles, Mumps and Rubella) and DTP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) containing vaccines in use in Albania during the last 10 years, in order to confirm the stability of immunization program. One of the reasons for coverage improvement is the use of one or two-dose vials for the administration of MMR vaccine, enabling the vaccination of children at any time, without the need of gathering them on certain days when the multi-dose vaccine vials are opened. In the last three years, according to WHO recommendations, it was noted that vaccination coverage with three doses containing DTP is at sustainable levels, always above 95%, but for our country this value goes sometimes above 98%. As for the use of pentavalent vaccine, from 2008, DTP-HepB-Hib, also the coverage of Hepatitis b vaccine is always at upper levels due to its use on 5 in 1 combination. The application of this vaccine was associated with the use of one dose vial administration, therefore one vaccine to a child. -

Vaccine Information Program

1 How to access translation • On the toolbar at the bottom of your screen, select the “Interpretation” button. • Select the language you would like to listen to. Date Date • How to access Spanish and Portuguese translation • Introduction of panel • Overview of local data • How vaccines work • Vaccine development and safety • Side effects Welcome! • State vaccination strategy • Vaccine priority groups • After vaccination • Where to get vaccinated • Support for accessing vaccines • Q & A 3 Why I am choosing vaccination • Mayor Edward Bettencourt Why I am choosing vaccination • Dr. Alain Chaoui, MD • I chose to get the vaccine to protect my patients, my family and my community and to take part in eradicating Covid-19. Why I am choosing vaccination Dr. Laura Holland, MD • I took the vaccine because I researched the safety and concluded that it was safe and effective. • I took it to protect myself, my family and my patients. 7 Why I am choosing vaccination • Grace Martins, RN • I decided to get the vaccine because as a Registered Nurse I am in constant contact with patients and staff. I am also in the high risk category because I am a diabetic on Insulin. • For my own health and the safety of those I take care of, I decided I needed to be protected from this virus! Why I am choosing vaccination • Cari Pacheco, LPN • I had no doubts about getting the vaccine due to the love I have for my family, friends, people in the community and my work environment. • I need to protect myself in order to be able to care for others • I want to protect myself as much as I can so I will not bring any illnesses to the people I love. -

2021 Medicare Vaccine Coverage Part B Vs Part D

CDPHP® Medicare Advantage Vaccine Coverage Guide Part B (Medical) vs. Part D (Pharmacy) Medicare Part B (Medical): Medicare Part D (Pharmacy): Vaccinations or inoculations Vaccinations or inoculations are included when the administration is (except influenza, pneumococcal, reasonable and necessary for the prevention of illness. and hepatitis B for members at risk) are excluded unless they are directly related to the treatment of an injury or direct exposure to a disease or condition. • Influenza Vaccine (Flu) • BCG Vaccine • Pneumococcal Vaccine • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis Vaccine (ADACEL, (Pneumovax, Prevnar 13) BOOSTRIX, DAPTACEL, INFANRIX) • Hepatitis B Vaccine • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis/Inactivated Poliovirus (Recombivax, Engerix-B) Vaccine (KINRIX, QUADRACEL) for members at moderate • Diphtheria/Tetanus Vaccine (DT, Td, TDVAX, TENIVAC) to high risk • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis/Inactivated Poliovirus Vac • Other vaccines when directly cine/ Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Conjugate Vaccine (PENTACEL) related to the treatment of an • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis/Inactivated Poliovirus injury or direct exposure to a Vaccine/Hepatitis B Vaccine (PEDIARIX) disease or condition, such as: • Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Conjugate Vaccine (ActHIB, PedvaxHIB, • Antivenom Sera Hiberix) • Diphtheria/Tetanus Vaccine • Hepatitis A Vaccine, Inactivated (VAQTA) (DT, Td, TDVAX, TENIVAC) • Hepatitis B Vaccine, Recombinant (ENGERIX-B, RECOMBIVAX HB) • Rabies Virus Vaccine for members at low risk (RabAvert, -

Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Many Vaccines Are Documented in an Abbreviation and Not by Their Full Name

Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Vaccine Names and Abbreviations Many vaccines are documented in an abbreviation and not by their full name. This page is designed to assist you in interpreting both old and new immunization records such as the yellow California Immunization Record, the International Certificate of Vaccination (Military issued shot record) or the Mexican Immunization Card described in the shaded sections. Vaccine Abbreviation/Name What it Means Polio Oral Polio oral poliovirus vaccine (no longer used in U.S.) OPV Orimune Trivalent Polio TOPV Sabin oral poliovirus Inactivated Polio injectable poliovirus vaccine eIPV IPOL IPV Pentacel combination vaccine: DTaP/Hib/IPV Pediarix combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae type b and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP/IPV/Hep B) DTP or DPT combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (no longer DTP Tri-Immunol available in U.S.) (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis) Triple combination vaccine: difteria, tétano, tos ferina (diphtheria, tetanus pertussis) DT combination vaccine: diphtheria and tetanus vaccine (infant vaccine without pertussis component used through age 6) DTaP combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis DTaP/Tdap Acel-Imune Certiva (Diphtheria, Tetanus, acellular Daptacel Pertussis) Infanrix Tripedia Tdap combination vaccine: tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis Adacel (improved booster vaccine containing pertussis for adolescents Boostrix and adults) DTP-Hib combination vaccine: diphtheria, tetanus, -

Facts About Tetanus for Adults

Facts About Tetanus for Adults What is tetanus? Tetanus, commonly called lockjaw, is caused by a bacterial toxin, or poison, that affects the nervous system. It is contracted through a cut or wound that becomes contaminated with tetanus bacteria. The bacteria can get in through even a tiny pinprick or scratch, but deep puncture wounds or cuts like those made by nails or knives are especially susceptible to infection with tetanus. Tetanus bacteria are present worldwide and are commonly found in soil, dust and manure. Tetanus causes severe muscle spasms, including “locking” of the jaw so the patient cannot open his/her mouth or swallow, and may lead to death by suffocation. Tetanus is not transmitted from person to person. Prevention Symptoms Vaccination is the only way to protect against tetanus. Due Common first signs of tetanus include muscular stiffness in to widespread immunization, tetanus is now a rare disease the jaw (lockjaw) followed by stiffness of the neck, in the U.S. A booster immunization against tetanus is difficulty in swallowing, rigidity of abdominal muscles, recommended every 10 years. A new combination vaccine, generalized spasms, sweating and fever. called Tdap, protects against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis, and should be used for persons 11-64 years Symptoms usually begin 7 days after bacteria enter the instead of Td (tetanus-diphtheria vaccine). Td should be body through a wound, but this incubation period may used for adults 65 years and older. Adolescents and adults range from 3 days to 3 weeks. who have never received immunization against tetanus should start with a 3-dose primary series given over 7 to 12 months. -

Adverse Effects of Vaccines Evidence and Causality

REPORT BRIEF AUGUST 2011 .For more information visit www.iom.edu/vaccineadverseeffects Adverse Effects of Vaccines Evidence and Causality Immunizations are a cornerstone of the nation’s efforts to protect people from a host of infectious diseases. As required by the Food and Drug Admin- istration, vaccines are tested for safety before they enter the market, and their performance is continually evaluated to identify any risks that might appear over time. Vaccines are not free from side effects, or “adverse effects,” but most are very rare or very mild. Importantly, some adverse health problems following a vaccine may be due to coincidence and are not caused by the vaccine. As part of the evaluation of vaccines over time, researchers assess evidence to deter- As part of the evaluation of mine if adverse events following vaccination are causally linked to a specific vaccines over time, researchers vaccine, and if so, they are referred to as adverse effects. Under the National assess evidence to determine if Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986, Congress established the National Vac- adverse events following cine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) to provide compensation to peo- vaccination are causally linked to ple injured by vaccines. Anyone who thinks they or a family member—often a a specific vaccine, and if so, they are referred to as adverse effects. child—has been injured can file a claim. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the agency within the Department of Health and Human Services that administers VICP, can use evidence that demonstrates a causal link between an adverse event and a vaccine to streamline the claim process. -

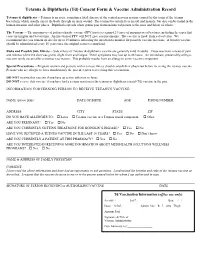

Tetanus & Diphtheria (Td) Consent Form & Vaccine Administration

Tetanus & Diphtheria (Td) Consent Form & Vaccine Administration Record Tetanus & diphtheria -- Tetanus is an acute, sometimes fatal, disease of the central nervous system, caused by the toxin of the tetanus bacterium, which usually enters the body through an open wound. The tetanus bacterium lives in soil and manure, but also can be found in the human intestine and other places. Diphtheria spreads when germs pass from an infected person to the nose and throat of others. The Vaccine -- The pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) protects against 23 types of pneumococcal bacteria, including the types that cause meningitis and bacteremia. An injection of PPV will NOT give you pneumonia. The vaccine is made from a dead virus. We recommend that you remain on site for up to 15 minutes following the injection to monitor for possible vaccine reactions. A booster vaccine should be administered every 10 years once the original series is completed. Risks and Possible Side Effects -- Side effects of Tetanus & diphtheria vaccine are generally mild in adults. These reactions consist of pain and redness where the shot was given, slight fever and fatigue. These symptoms may last up to 48 hours. An immediate, presumably allergic, reaction rarely occurs after a tetanus vaccination. This probably results from an allergy to some vaccine component. Special Precautions -- Pregnant women and persons with a serious illness should consult their physician before receiving the tetanus vaccine. Persons who are allergic to latex should notify the provider prior to receiving this vaccination. DO NOT receive this vaccine if you have an active infection or fever. DO NOT receive this vaccine if you have had a serious reaction to the tetanus or diphtheria toxoid (Td) vaccine in the past. -

Adult Occupational Immunizations Massachusetts Recommendations and Requirements for 2015

Adult Occupational Immunizations Massachusetts Recommendations and Requirements for 2015 Recommended Immunizations For Health Care Personnel (HCP) Vaccine Recommendations in Brief Influenza 1 dose of flu vaccine every flu season. Tdap/Td (Tetanus, 1 dose of Tdap as soon as possible, then Td boosters every 10 years. diphtheria, pertussis) MMR (Measles, mumps, 2 doses of MMR, > 28 days apart or documented laboratory-confirmed immunity to measles rubella) and mumps and rubella. Varicella 2 doses of varicella vaccine, or serologic proof of immunity, or history of varicella disease Hepatitis B 3-dose series (see footnote) Meningococcal 1 dose of quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine for microbiologists who are routinely exposed to N. meningitidis isolates. Health care personnel (HCP) include full- and part-time apart; laboratory evidence of immunity or laboratory staff with or without direct patient contact, including confirmation of disease; diagnosis of history of varicella physicians, students, and volunteers who work in inpatient, disease or herpes zoster by a health-care provider, outpatient and home-care settings. See Immunization of including school or occupational health nurse. Health-Care Personnel - Recommendations of the ACIP. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6007.pdf Hepatitis B: HCP should receive 3 doses hepatitis B vaccine on a 0, 1, and 6 month schedule. Test for Influenza: All HCP should receive annual flu vaccine. hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) 1–2 months after Give inactivated flu vaccine (IIV) to any HCP. Give live, 3rd dose to document immunity. HCP and trainees in attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to non-pregnant certain populations at high risk for chronic hepatitis B (e.g., healthy HCP < 49 years of age.