Payette Merged Master Submit Finalv2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

Wood County – March 9Th, 2018 Preliminary Report

Nourishing Networks Workshop Wood County – March 9th, 2018 Preliminary Report 0 Nourishing Networks Wood County: Workshop Reflections and Report Authors: Dr. Bradley R. Wilson, Director, Food Justice Lab Heidi Gum, Coordinator, Nourishing Networks Program Facilitators: Dr. Bradley Wilson, Food Justice Lab Director Jessica Arnold, Community Food Initiatives Jed DeBruin, Food Justice Fellow Kelly Fernandez, Community Food Initiatives Thomson Gross, Food Justice Lab GIS Research Director Heidi Gum, Nourishing Networks Coordinator Joshua Lohnes, Food Justice Fellow Amanda Marple, Food Justice Fellow Ashley Reece, Food Justice Laboratory VISTA Raina Schoonover, Community Food Initiatives Participants: Amy Arnold - United Way Alliance of the MOV Sister Molly Bauer - Sisters Health Foundation Judith Boston - Fairlawn Baptist Church Food Pantry and Wood County Emergency Food Co-op Andy Church – United Way Alliance of the MOV Marian Clowes - Parkersburg Area Community Foundation and Regional Affiliates Kristy Cramlet - Highmark Health Gwen Crum - WVU Wood County Extension (continued on next page) 1 Dianne Davis - Lynn Street Church of Christ Laura Dean – Mt. Pleasant Food Pantry Lisa Doyle-Parsons - Circles Campaign of the Mid-Ohio Valley Kayla Ersch - Community Resources Inc. Amy Gherke - The Salvation Army Shirley Grogg - The Salvation Army Sara Hess - United Way Alliance of the MOV Kayla Hinkley - Try This WV Sherry Hinton - Sak Pak Delaney Laughery - United Way Alliance of the MOV Jeremy Lessner - Catholic Charities of WV Andrew Mayle - Mid-Ohio -

Universidade Federal Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas Escola De Comunicação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO CLARISSA MONTALVÃO VALLE DA SILVA HOUSE M.D.: UM ESTUDO DE CASO DA ESTRUTURA NARRATIVA SERIAL COMPLEXA Rio de Janeiro 2011 UM ESTUDO DE CASO DA ESTRUTURA NARRATIVA SERIAL COMPLEXA Clarissa Montalvão Valle da Silva HOUSE M.D.: um estudo de caso da estrutura narrativa serial complexa Monografia submetida à Escola de Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Radialismo Orientador: Prof. Dr. Maurício Lissovsky. Rio de Janeiro 2011 Clarissa Montalvão Valle da Silva HOUSE M.D.: um estudo de caso da estrutura narrativa serial complexa Monografia submetida à Escola de Comunicação da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Radialismo. Rio de Janeiro, 14 de dezembro de 2011 _________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Maurício Lissovsky, ECO/UFRJ _________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Ivan Capeller, ECO/UFRJ _________________________________________________ Profª Drª Ieda Tucherman, ECO/UFRJ _________________________________________________ Profa Dra Fátima Sobral Fernandes, ECO/UFRJ AGRADECIMENTOS Quero agradecer a todos que me deram força, apoio, palavras de confiança e incentivo, o que me ajudou muito a fazer esta monografia. Se não fosse por vocês, eu provavelmente teria sentado e deixado o tempo passar. Agradeço aos meus pais, Patricia e Marcos, e à minha irmã, Isabela, que sempre acreditaram em mim. Desculpem a angustia que fiz vocês passarem me vendo nervosa e na correria. À Tati, que mais do que uma tia, foi uma contente ajudante de revisão de texto e me deu muito apoio. -

One Big Happy Episode Guide Episodes 001–006

One Big Happy Episode Guide Episodes 001–006 Last episode aired Tuesday April 28, 2015 www.nbc.com c c 2015 www.tv.com c 2015 www.nbc.com The summaries and recaps of all the One Big Happy episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http: //www.nbc.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Out of the Closet . .5 3 Crushing It . .7 4 Flight Risk . .9 5 A Tale of Two Hubbies . 11 6 Wedlocked . 13 Actor Appearances 15 One Big Happy Episode Guide II Season One One Big Happy Episode Guide Pilot Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Tuesday March 17, 2015 Writer: Liz Feldman Director: Scott Ellis (I) Show Stars: Elisha Cuthbert (Lizzy), Nick Zano (Luke), Kelly Brook (Prudence), Re- becca Corry (Leisha), Chris Williams (Roy), Brandon Mychal Smith (Marcus) Guest Stars: Edwin H. Bravo (Paint Store Guy), Michelle Noh (Pharmacist) Production Code: 276080 Summary: Luke and Lizzy, inseparable pals since childhood, decide to have a child together as friends. Childhood best friends Lizzy and Luke de- cided long ago that if they were both sin- gle at 30, they’d start a family together — just not the old fashioned way. Lizzy is a lesbian and Luke is straight. ”We may not be everyone’s idea of a traditional fam- ily,” Lizzy says to the pharmacist provid- ing her pre-prenatal pills, ”but my point is we’re still good people with solid val- ues.” With parenthood a positive pregnancy test away, Lizzy asks Luke if he’s ready for such a commitment, especially since he never even lets his dates spend the night. -

City Free of TB Deaths Last Year, First Since 1956

FPfE PUBLIC LIBRARY iUMMH, NEW »f'•'•'* 1889,1964 1889-1964 Seventy-Five Years Seventy-Five Years Of Continous Of Continous Public Service Public Service «VM. Summit Record 76th Year No. 11 Cntara* u ••oonl CUM llutir at lha POM Offloa at Bommlt. N. J. iim. Dadar tHa ACT •( Hank a, lift CRestview 3-4000 SUMMIT, N. J., THURSDAY, JULY 30, 1964 0*coDd ClaM PoiUx* Paid at Summit. N. J. $6 a y..r IS CLMTS Varied Activities Keep City Free of TB Summer Playground Participants On Go Deaths Last Year, Pet fairs, crazy hair-do's, lollipop hunts, shoe throws I and trying to whistle while eating crackers, were among! the several kinds of activities that kept participants busy First Since 1956 last week at the city's five summer playgrounds. Memorial Field For the first time since 19SS no deaths from tuber- Highlight of Friday morning culosis were recorded in the city last yetr, a Board of was a stuffed animal show. Best Health report disclosed this week. Summit Trust New Law Suit The number of tuberculosis cases for the year num- in show was awarded to Debby bered three, the same as in 1962; but during that year Sperco's gigantic lion, Leo. one death wai reported. Other priies went to the follow- Filed Against In 19M, when no deaths were ling people: Susan Hall-most And Elizabeth reported, there were 14 cases of elegant; Sara Hess-biggest ears; Births Beat the disease in the dry. Angelo DiOnno-cutest;- Ginny The report also indicated that Bank Merging Master Plan venereal disease in the city, Sperco-best cared for; Doug particularly syphilis, is "on the A taxpayer suit to recover a Hall-coolest cat; David Dumais- Plans for the merging of two Deaths Here increase." The Board of Health 120,300 fee allegedly paid by the most sophisticated; Debby Ro-'ot Union County's oldest banks, reported that syphilis has be- city to its Master Plan consul- bison-most original; Barbara the Summit Trust Co. -

PDF of This Issue

Established 1881 WEATHER, p. 2 MIT’s Oldest and Fri: 48°F | 33°F Largest Newspaper Partly cloudy sat: 49°F | 34°F Sunny tech.mit.edu SUN: 50°F | 39°F Sunny Established 1881 Volume 132, Number 54 Friday, November 16, 2012 W20 to get card readers soon Le Meridien workers Student center will be card access only starting Tuesday continue campaign Labor dispute with HEI ongoing By Sara Hess would remain neutral in the dispute between Le Meridien workers and Established 1881 Yesterday evening, between 4 - 6 management. p.m. a picket line with approximately “It seems disingenuous for MIT to 30 participants including Le Meridien claim a neutral stance on this debate hotel workers, union organizers, and when they own the property and list MIT students gathered in front of the the hotel as a preferred vendor. As a hotel located at 20 Sidney Street. Pick- member of the MIT community I feel eters called for hotel guests to sup- that I could and should do something port a worker-led boycott by check- about this”, Neugebauer said last night ing out of the hotel. The picket line at the protest. was planned for last night in order to Neugebauer is not alone. 14 MIT attract the attention of hotel guests faculty members have signed a docu- who are participating in the Eastern ment stating their support of the boy- Division of the Community College cott. Union organizers are also making Humanities Association conference, efforts to reach out to MIT student which is scheduled to take place at Le organizations such as the Students of Meridien from November 15th-17th. -

Fame Program

SPECIAL THANKS Jeannine Gamble Beverly J Martin Lily Cedarbaum Emily Hess Elementary School Will Lloyd Denise Gomber Ithaca College Theatre Steve Kern Larry Cutler Lilly Westbrook Jennifer Engel Steve Kellerman Lee Byron Cat’s Pajamas Karen Friedeborn Colin Stewart Darrell Isham Ithaca Youth Bureau Johnny Kontogiannis Russell Maitland Dryden Central School Eric Yaple Warren Helms District David and Diane King Kerry Mizrahi Norm Johnson Barney Schug George Belokur Sara Hess & Jeff Furman Heather Stewart Erica Steinhagen And the families and friends of the cast and crew for their support! DIRECTOR’S NOTES One year ago, I was thinking to myself, “What do I want to do when I grow up? What’s my dream?” Okay, so it might have the millionth time I asked myself that, but I finally found an answer that made sense and excited me as much as an answer to that question ought to excite a person: Start a community theatre for young artists in this area. I grew up lucky. In northern New Jersey, I was a part of a remarkable community theatre company, Song & Dance Associates. We did several shows per year – big musicals, big casts, the works. It’s where I learned everything I knew about theatre prior to college. More importantly, it’s where I met my best friends and found an extended family that I am a part of to this day. It seemed that there was a void that needed filling in our community. What a surplus of talented, eager, energetic, ambitious, and dedicated young people there are around here! They do incredible work in their school shows, but typically only get one or two per year. -

Embargoed Until 8:35Am Pt on July 16, 2015

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:35AM PT ON JULY 16, 2015 67th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2014 – May 31, 2015 Los Angeles, CA, July 16, 2015– Nominations for the 67th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Uzo Aduba from the Netflix series Orange Is The New Black and Cat Deeley, the host of FOX’s So You Think You Can Dance. "This was truly a remarkable year in television,” said Rosenblum. “From the 40th Anniversary of Saturday Night Live, to David Letterman’s retirement and the conclusion of Mad Men, television’s creativity, influence and impact continue to grow and have never been stronger. From broadcast, to cable to digital services, our industry is producing more quality television than ever before. Television is the pre-eminent entertainment platform with extraordinarily rich and varied storytelling. The work of our members dominates the cultural discussion and ignites the passion of viewers around the world. All of us at the Academy are proud to be honoring the very best in television.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees included newcomers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: Transparent and UnBreakaBle Kimmy Schmidt in the Outstanding Comedy Series category and Better Call Saul in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, Parks And Recreation returns to vie for Outstanding Comedy Series while Homeland is back in the running for Outstanding Drama Series. Orange Is The New Black is nominated for its second consecutive season, but in the drama category, following an Academy- sanctioned switch from last year’s comedy nomination. -

House Episode 8 Season 4

House episode 8 season 4 Drama · A magician's heart stops during a performance. At first House dismisses the case, but Season 4 | Episode 8. Previous · All Episodes () · Next · You Don't Want to Know Poster. A magician's heart stops during a performance. At first House. A magician's heart stops during a performance. At first House dismisses the case, but later changes his mind when complications arise. House has a contest to. "You Don't Want To Know" is the eighth episode of the fourth season of the American TV drama House "You Don't Want To Know". House episode. Episode no. Season 4. Episode 8. Directed by, Lesli Linka Glatter. Written by, Sara Hess.Plot · Medicine · Contest · Thirteen. The TV Show House M.D episode 8 offers All episodes can watched live series House M.D. You Don't Want to Know is a fourth season episode of House which first aired on November Season Four, Episodes 71 - House MD Season 4. Season Premiere, September 25, Season Finale, May 19, Season Guide. previous. Season. As in previous years, I'm binge-reviewing the latest season of Netflix's House of Cards, the TV show that helped popularize the idea of “binge. Season 4, Episode 8: 'Chapter 47'. As the Underwoods's presidential election plan of shifts into an even faster gear, “House of Cards”. The Conways pile on the pressure, but Team Underwood has their own schemes afoot in the latest episode. Read the recap review at Empire. Watch Flip This House: A Well of a Tale from Season 4 at How Clean Is Your House Season 4 Episode 8 PLEASE SUBSCRIBE How Clean Is Your House. -

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2014 Edison Ballroom 240 West 47Th Street • NYC

The Writers Guild of America, East Presents SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2014 Edison Ballroom 240 West 47th Street • NYC FEBRUARY 1, 2014 EDISON BALLROOM 1 2 The 66th Annual Writers Guild Awards SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2014 • EDISON BALLROOM • NEW YORK CITY Officers Lowell Peterson Michael Winship: President Executive Director Jeremy Pikser: Vice President Bob Schneider: Secretary–Treasurer Ruth Gallo Assistant Executive Director Council Members John Auerbach Marsha Seeman Henry Bean Assistant Executive Director Walter Bernstein Sue “Bee” Brown Awards Committee Arthur Daley Bonnie Datt, Chair Bonnie Datt Ann B. Cohen Terry George Gail Lee Gina Gionfriddo John Marshall Susan Kim Allan Neuwirth Jenny Lumet Danielle Paige Patrick Mason Courtney Simon Zhubin Parang Richard Vetere Phil Pilato Bernardo Ruiz Ted Schreiber Dana Weissman Lara Shapiro Director of Programs Courtney Simon Duane Tollison Nancy Hathorne Richard Vetere Events Coordinator Jason Gordon Director of Communications PKPR Red Carpet 3 DRAMA SERIES MAD MEN Written by Matthew Weiner André Jacquemetton Maria Jacquemetton Janet Leahy Semi Chellas Erin Levy Lisa Albert Michael Saltzman Tom Smuts Jonathan Igla Jason Grote Carly Wray CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR WRITERS GUILD AWARDS NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES BREAKING BAD Written by Vince Gilligan Sam Catlin Peter Gould George Mastras Thomas Schnauz Moira Walley-Beckett Gennifer Hutchison EPISODIC DRAMA “BURIED” Written by Thomas Schnauz “CONFESSIONS” Written by Gennifer Hutchison “GRANITE STATE” Written by Peter Gould © 2014 AMC Network Entertainment LLC. All rights reserved. AMC 3752 BRIAN S. Version: BLACK AND WRITERS GUILD OF AMERICA WHITE AD FULL PAGE NO BLEED 150 N/A 4.5"W X 7.5"H REVISED 1/10/14 client and prod special info: # A-004 job#1537F artistBRIAN S. -

Don T Wait Any Longer, Take a Look at the First Official Images from HOUSE of the DRAGON

Don’t Wait Any Longer, Take a Look at the First Official Images From HOUSE OF THE DRAGON HBO has released the first official images from the upcoming drama series, HOUSE OF THE DRAGON. Based on George R. R. Martin’s “Fire & Blood,” the series, which is set 300 years before the events of GAME OF THRONES, tells the story of House Targaryen. HOUSE OF THE DRAGON recently began production and will debut on HBO Max and HBO in 2022. Featured cast include the following: Emma D’Arcy as Princess Rhaenyra Targaryen: The king’s first-born child, she is of pure Valyrian blood, and she is a dragonrider. Many would say that Rhaenyra was born with everything… but she was not born a man. Matt Smith as Prince Daemon Targaryen: The younger brother to King Viserys and heir to the throne. A peerless warrior and a dragonrider, Daemon possesses the true blood of the dragon. But it is said that whenever a Targaryen is born, the gods toss a coin in the air… Steve Toussaint as Lord Corlys Velaryon, “The Sea Snake”: Lord of House Velaryon, a Valyrian bloodline as old as House Targaryen. As “The Sea Snake,” the most famed nautical adventurer in the history of Westeros, Lord Corlys built his house into a powerful seat that is even richer than the Lannisters and that claims the largest navy in the world. Olivia Cooke as Alicent Hightower: The daughter of Otto Hightower, the Hand of the King, and the most comely woman in the Seven Kingdoms. She was raised in the Red Keep, close to the king and his innermost circle; she possesses both a courtly grace and a keen political acumen. -

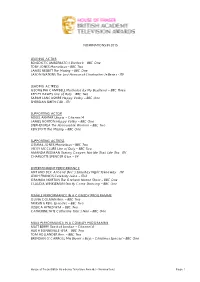

NOMINATIONS in 2015 LEADING ACTOR BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Sherlock – BBC One TOBY JONES Marvellous – BBC Two JAMES NESBITT

NOMINATIONS IN 2015 LEADING ACTOR BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Sherlock – BBC One TOBY JONES Marvellous – BBC Two JAMES NESBITT The Missing – BBC One JASON WATKINS The Lost Honour of Christopher Jefferies - ITV LEADING ACTRESS GEORGINA CAMPBELL Murdered by My Boyfriend – BBC Three KEELEY HAWES Line of Duty – BBC Two SARAH LANCASHIRE Happy Valley – BBC One SHERIDAN SMITH Cilla - ITV SUPPORTING ACTOR ADEEL AKHTAR Utopia – Channel 4 JAMES NORTON Happy Valley – BBC One STEPHEN REA The Honourable Woman – BBC Two KEN STOTT The Missing – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTRESS GEMMA JONES Marvellous – BBC Two VICKY MCCLURE Line of Duty – BBC Two AMANDA REDMAN Tommy Cooper: Not like That, Like This - ITV CHARLOTTE SPENCER Glue – E4 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE ANT AND DEC Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway – ITV LEIGH FRANCIS Celebrity Juice – ITV2 GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One CLAUDIA WINKLEMAN Strictly Come Dancing – BBC One FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME OLIVIA COLMAN Rev. – BBC Two TAMSIN GREIG Episodes – BBC Two JESSICA HYNES W1A – BBC Two CATHERINE TATE Catherine Tate’s Nan – BBC One MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME MATT BERRY Toast of London – Channel 4 HUGH BONNEVILLE W1A – BBC Two TOM HOLLANDER Rev. – BBC Two BRENDAN O’CARROLL Mrs Brown’s Boys – Christmas Special – BBC One House of Fraser British Academy Television Awards – Nominations Page 1 SINGLE DRAMA A POET IN NEW YORK Aisling Walsh, Ruth Caleb, Andrew Davies, Griff Rhys Jones - Modern Television/BBC Two COMMON Jimmy McGovern, David Blair, Colin McKeown, Donna Molloy – LA Productions/BBC One MARVELLOUS Peter Bowker, Julian Farino, Katie Swinden, Patrick Spence – Fifty Fathoms/BBC Two MURDERED BY MY BOYFRIEND Pier Wilkie, Regina Moriarty, Paul Andrew Williams, Darren Kemp – BBC/BBC Three MINI-SERIES CILLA Jeff Pope, Paul Whittington, Kwadjo Dajan, Robert Willis - ITV Studios/GroupM Entertainment/ITV THE LOST HONOUR OF CHRISTOPHER JEFFERIES Gareth Neame, Peter Morgan, Roger Michell, Kevin Loader - Carnival Film and Television in assoc.