123Community Tourism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sitios Arqueológicos De Ponce

Sitios Arqueológicos de Ponce RESUMEN ARQUEOLÓGICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE PONCE La Perla del Sur o Ciudad Señorial, como popularmente se le conoce a Ponce, tiene un área de aproximadamente 115 kilómetros cuadrados. Colinda por el oeste con Peñuelas, por el este con Juana Díaz, al noroeste con Adjuntas y Utuado, y al norte con Jayuya. Pertenece al Llano Costanero del Sur y su norte a la Cordillera Central. Ponce cuenta con treinta y un barrios, de los cuales doce componen su zona urbana: Canas Urbano, Machuelo Abajo, Magueyes Urbano, Playa, Portugués Urbano, San Antón, Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto y Sexto, estos últimos seis barrios son parte del casco histórico de Ponce. Por esta zona urbana corren los ríos Bucaná, Portugués, Canas, Pastillo y Matilde. En su zona rural, los barrios que la componen son: Anón, Bucaná, Canas, Capitanejo, Cerrillos, Coto Laurel, Guaraguao, Machuelo Arriba, Magueyes, Maragüez, Marueño, Monte Llanos, Portugués, Quebrada Limón, Real, Sabanetas, San Patricio, Tibes y Vallas. Ponce cuenta con un rico ajuar arquitectónico, que se debe en parte al asentamiento de extranjeros en la época en que se formaba la ciudad y la influencia que aportaron a la construcción de las estructuras del casco urbano. Su arquitectura junto con los yacimientos arqueológicos que se han descubierto en el municipio, son parte del Inventario de Recursos Culturales de Ponce. Esta arquitectura se puede apreciar en las casas que fueron parte de personajes importantes de la historia de Ponce como la Casa Paoli (PO-180), Casa Salazar (PO-182) y Casa Rosaly (PO-183), entre otras. Se puede ver también en las escuelas construidas a principios del siglo XX: Ponce High School (PO-128), Escuela McKinley (PO-131), José Celso Barbosa (PO-129) y la escuela Federico Degetau (PO-130), en sus iglesias, la Iglesia Metodista Unida (PO-126) y la Catedral Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (PO-127) construida en el siglo XIX. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimosexta Asamblea Legislativa Quinta Sesion Ordinaria Año 2011 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOSEXTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA QUINTA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2011 VOL. LIX San Juan, Puerto Rico Miércoles, 12 de enero de 2011 Núm. 2 A las once y treinta y ocho minutos de la mañana (11:38 a.m.) de este día, miércoles, 12 de enero de 2011, el Senado reanuda sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia de la señora Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Vicepresidenta. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Roberto A. Arango Vinent, Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Luis A. Berdiel Rivera, Eduardo Bhatia Gautier, Norma E. Burgos Andújar, José L. Dalmau Santiago, José R. Díaz Hernández, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora, Alejandro García Padilla, Sila María González Calderón, José E. González Velázquez, Juan E. Hernández Mayoral, Héctor Martínez Maldonado, Angel Martínez Santiago, Luis D. Muñiz Cortés, Eder E. Ortiz Ortiz, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Itzamar Peña Ramírez, Kimmey Raschke Martínez, Carmelo J. Ríos Santiago, Thomas Rivera Schatz, Melinda K. Romero Donnelly, Luz M. Santiago González, Lawrence Seilhamer Rodríguez, Antonio Soto Díaz, Lornna J. Soto Villanueva, Jorge I. Suárez Cáceres, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Carlos J. Torres Torres, Evelyn Vázquez Nieves y Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Vicepresidenta. SRA. VICEPRESIDENTA: Se reanudan los trabajos del Senado de Puerto Rico hoy, miércoles, 12 de enero de 2011, a las once y treinta y ocho de la mañana (11:38 a.m.). SR. ARANGO VINENT: Señora Presidenta. SRA. VICEPRESIDENTA: Señor Portavoz. SR. ARANGO VINENT: Señora Presidenta, solicitamos que se comience con la Sesión Especial en homenaje a Roberto Alomar Velázquez, por haber sido exaltado al Salón de la Fama del Béisbol de las Grandes Ligas. -

City of Hallandale Beach Economic Development Strategy

City of Hallandale Beach Economic Development Strategy City of Hallandale Beach Economic Development Strategy - Nov 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: CITY OF HALLANDALE BEACH – ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY BRIEF 4 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND TO THE HALLANDALE BEACH MARKET 4 Section 2A: Demographics of Community and Changes over Time 8 Population and Households 8 Age of Population 9 Race and Ethnicity 10 Household Income 12 Section 2B: Comparative Demographics of Hallandale to Surrounding Cities 13 Population 13 Age 14 Race and Ethnicity 14 Household Income 15 Section 2C: Unemployment and Workforce Profile and Projections 16 Section 2D: Hallandale Beach Traffic Counts 18 Section 2E: Market Background Conclusions 19 SECTION 3: PROFILE OF CURENT REAL ESTATE TRENDS AND OUTLOOK 21 Section 3A: Broward County and City of Hallandale Beach – Housing Sales Activity 21 Assessed and Taxable Values 22 Section 3B: Broward Office Market Overview 23 Section 3C: Retail Market Analysis 25 Retail Demand Analysis Section 3D: Industrial Market Overview 30 Section 3E: Tourism/Hospitality Market Overview 33 Section 3F: Real Estate Conclusions 35 2 City of Hallandale Beach Economic Development Strategy - Nov 2011 SECTION 4: FOCUSING ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT EFFORTS 36 Section 4A: Leverage Hallandale Beach’s Strength for Future Development 36 Section 4B: Developable Nodes/Parcels 39 Section 4C: Recommended Development Focus 41 SECTION 5: THE CITY OF HALLANDALE BEACH’S ROLE IN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 43 Section 5A: Target Industries/Principal Land Uses 43 Section 5B: Economic -

Listado Comparativo De Edificios Y Lugares Históricos De Puerto Rico

Listado Comparativo de Edificios y Lugares Históricos de Puerto Rico Nombre 1 Nombre 2 NRHP Fecha Inclusion NRHP JP # de Resolución Fecha Notificacion JP ADJUNTAS Puente de las Cabañas Bridge #279 X 07/19/1995 X 2000-(RC)-22-JP-SH 04/03/2001 Quinta Vendrell Granja San Andrés X 02/09/2006 X 2008-34-01-JP-SH 10/22/2008 Escuela Washington Irvin X 05/26/2015 AGUADA Puente del Coloso Puente Núm. 1142 X 12/29/2010 Casa de la Sucesión Mendoza Patiño X 2006-26-01-JP-SH 02/15/2006 AGUADILLA Casa de Piedra Residencia Amparo Roldán X 04/03/1986 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Faro de Punta Borinquén Punta Borinquén Light X 10/22/1981 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Iglesia de San Carlos Borromeo X 10/22/1981 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Antiguo Cementerio Municipal X 01/02/1985 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Corte de Distrito Museo de Arte de Aguadilla X 01/02/1985 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Residencia Cardona Bufete Quiñones Elias X 01/02/1985 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Fuerte de la Concepción El fuerte; Escuela Carmen Gómez Tejera X 01/02/1985 El Parterre Ojo de Agua X 01/02/1985 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Residencia López Residencia Herrera López X 01/02/1985 X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH Residencia Beneián X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Edificio de Apartamentos X 2000-(RO)-19-JP-SH 01/16/2001 AGUAS BUENAS Parque de Maximiliano Merced; Antiguo Parque de Bombas de Parque de Bombas Maximiliano Merced Aguas Buenas X 11/12/2014 AIBONITO Iglesia San José X 12/19/1984 X 2016-01-01-JP-SH Villa Julita X 12/19/1986 X 2000-(RCE)-21-JP-SH 01/16/2001 Carretera Central Military Road; PR-1; PR-14 X 04/02/2019 AÑASCO Puente de Añasco Puente Núm. -

Study Tour to Puerto Rico A

STUDY TOUR TO PUERTO RICO - A NON-TRADITIONAL WAY OF LEARNING: AN ONGOING STUDY NASA Tri-State Consortium of Opportunity Programs in Higher Education 2011 Westchester Marriott, Tarrytown, New York Presenter: Evelyn (Santiago) Rosario, M.A. Director, Study Tour to Puerto Rico 1993-2009 Senior Academic Adviser, EOP, Buffalo State College GOALS To expose the Study Tour to Puerto Rico as a non-traditional way of learning to conference participants as a tool in assisting EOP and non- EOP students to: Participate in study abroad programs Enhance their academic and cultural experiences Employ it as an asset for employment and career development To increase EOP visibility by developing networks and collaborative efforts Within our campuses Outside our Institutions To encourage initiative as a means of professional and personal development To strengthen internationalization within our campuses OBJECTIVES To share: Ideas as Tools (Dave Ellis, Ph.D.) Knowledge & Experience in the course development Team approach Showcase the Trip portion of the Study Tour to Puerto Rico NASA OUTLINE Part 1: Course Development Course History 12 Power Processes Course Description Course Requirements Evaluation Student Comments Part 2: Study of STPR (11 Years) Study Abroad Profile Study Tour Pilot Project: 1993 -1996 Study Abroad: 1997- Present Part 3: Highlights of the Tour in Puerto Rico Visual Tour PART 1 STUDY TOUR TO PUERTO RICO 1993-2009 Course Development Implementation Evaluation PART 1.A. INTRODUCTION BUFFALO STATE COLLEGE MISSION […] is committed to the intellectual, personal, and professional growth of its students, faculty, and staff. The goal […] is to inspire a lifelong passion for learning, and to empower a diverse population of students to succeed as citizens of a challenging world. -

Tipo Centro De Votación Dirección Física

CENTROS DE VOTACIÓN FINAL PRIMARIAS DE LEY Rev. 15 de agosto 2020 DOMINGO, 16 DE AGOSTO DE 2020 10am Municipio Tipo Centro de Votación Dirección Física Unidad Precinto San Juan 003 16 Esc. San Martín (Ángeles Pastor) Cll. Luis Pardo, Urb. San Martín Vega Alta 016 01 C. Com Parcelas Cerro Gordo Carr. Principal, Parcelas Cerro Gordo Vega Alta 016 02 Esc. Francisco Felicie Martínez (Breñas) Carr. 693 Km. 14.1, Bo. Sabana Vega Alta 016 03 C. Com Carmelita Cll. 3 Comunidad Carmelita, Bo. Sabana Vega Alta 016 04 Esc. José Pagán (Nueva de Sabana Hoyos) Carr. 690 Km. 3.2, Bo. Sabana Hoyos Vega Alta 016 05 Esc. Rafael Hernández Cll. 3, Urb. Santa Ana Vega Alta 016 06 C. Com Bajura Sect. El Francés Calle Ucar, Esq. Acacia , Bo. Bajura Vega Alta 016 07 Esc. Elisa Dávila Vázquez Carr. 679 Km. 2.3, Sect. Fortuna Bo. Espinosa Adentro Vega Alta 016 08 Esc. Antonio Paoli Cll. 9, Urb. Santa Rita, Bo. Espinosa Vega Alta 016 09 Esc. Urbana Cll. Teodomiro Ramírez, Bo. Pueblo Vega Alta 016 10 Esc. Ignacio Miranda Cll. B, Urb. Las Colinas Bo. Espinosa Vega Alta 017 01 Esc. Apolo San Antonio Carr. 676 Esq. Cll.Luis MuÑoz Rivera Vega Alta 017 02 Cncha Bajo Techo Cienegueta Carr. 647, Bo. Cienegueta Vega Alta 017 03 Ctro. Complejo Recreo-Educativo Carr. 677 Km. 0.3, Bo. Maricao Vega Alta 017 04 Cncha Bajo Techo Candelaria Carr. 647 Km. 6.4 interior, Bo. Candelaria Vega Alta 017 05 Cncha Bajo Techo Mavilla Carr. 630 Km. 5.0, Bo. -

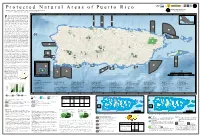

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Improving the EB-5 Investor Visa Program: International Financing for U.S

BROOKINGS-ROCKEFELLER Project on State and Metropolitan Innovation Improving the EB-5 Investor Visa Program: International Financing for U.S. Regional Economic Development Audrey Singer and Camille Galdes1 “ A reconsideration Summary of the EB-5 Difficulties in accessing traditional domestic financing brought on by the Great Recession, along with a rise in the number of wealthy investors in developing countries, have led to a recent regional center spike in interest in the EB-5 Immigrant Investor visa program. Through this federal visa program administered by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), immigrant investors may program can eventually secure permanent residency for themselves and their immediate family by investing at least $500,000 in a U.S. business and creating or preserving 10 full-time jobs. The majority of strengthen its EB-5 visas are currently administered through EB-5 regional centers, entities that pool invest- ments and are authorized to develop projects across a large swath of America’s metropolitan utility and better regions and rural areas. The focus of this paper is on the regional center program. Although utilization of EB-5 financing has increased dramatically in recent years as a source accomplish its of regional economic development, the program faces some major challenges. First, immigrant investors encounter a complicated network of intermediaries with little regulatory oversight, central goal of which discourages investment. Immigrants also bear the burden of compliance with program requirements, although they themselves have little control over the investment process. Second, aiding regional there is generally little coordination between regional centers and local economic development agencies (EDAs), even though these entities often share similar goals and could develop mutu- economic ally beneficial partnerships. -

Propiedades De Puerto Rico Incluidas En El Registro

PROPIEDADES DE PUERTO RICO INCLUIDAS EN EL REGISTRO NACIONAL DE LUGARES HISTORICOS Servicio Nacional de Parques Departamento de lo Interior de los Estados Unidos de América Oficina Estatal de Conservación Histórica OFICINA DE LA GOBERNADORA San Juan de Puerto Rico REVISADA: 20 de noviembre de 2020 POR: Sr. José E. Marull Especialista Principal en Propiedad Histórica REGISTRO NACIONAL DE LUGARES HISTORICOS Oficina Estatal de Conservación Histórica 20 de noviembre de 2020 Clave -Designación común de la propiedad; {Nombre según aparece en la lista del Registro Nacional de Lugares Históricos en Washington, D.C.}; <Otro nombre o designación utilizada para identificar la propiedad>; Dirección; (Fecha de inclusión: día, mes, año); Código del Servicio de Información del Registro Nacional, NRIS. ADJUNTAS, Municipio de Puente de las Cabañas - {Las Cabañas Bridge}; <Bridge #279>; Carretera Estatal #135, kilómetro 82.4; (19/JUL/95); 95000838. Quinta Vendrell - <Granja San Andrés>; Barrio Portugués, intersección de las Carreteras Estatales #143 y #123; (09/FEB/06); 06000028. Escuela Washington Irving – {Washington Irving Graded School}; Calle Rodulfo González esquina Calle Martínez de Andino; (26/MAYO/15); 15000274. AGUADA, Municipio de Puente de Coloso – <Puente Núm. 1142>; Carretera Estatal #418, kilómetro 5, Barrios Guanábano y Espinar; (29/DIC/10); 10001102. AGUADILLA, Municipio de Faro de Punta Borinquén - <Punta Borinquén Light>; Aledaño a la Carretera Estatal #107;(22/OCT/81); 81000559. Iglesia de San Carlos Borromeo - {Church San Carlos Borromeo of Aguadilla}; Localizada en la Calle Diego mirando a la plaza del pueblo; (18/SEPT/84); 84003124. Antiguo Cementerio - {Old Urban Cementery}; <Cementerio Municipal>; Localizado al pie de la montaña y playa cercana a la entrada norte del pueblo en el área llamada Cuesta Vieja; (02/ENE/85); 85000042. -

United States of America Immigration Options for Investors & Entrepreneurs

Chung, Malhas & Mantel, PLLC The Pioneer Building 600 First Avenue, Suite 400 Seattle, Washington 98104 Telephone: (206) 264-8999 Facsimile: (206) 264-9098 Skype: cmmrlawfirm.connect Website: www.cmmrlawfirm.com General Disclaimer: This booklet, all of its materials, and the illustrations contained herein are for general instructional and educational purposes only. They are not, and are not intended to provide, legal advice about what to do or not to do in any particular case. All data & information in this booklet is solely offered as examples. No person should rely on the materials or information in this booklet to make decisions about investing or participating in any EB-5 visa immigration program or non-immigrant investment visas without consulting with an attorney. If you have questions about the content contained in this booklet, please contact the law firm of CHUNG, MALHAS & MANTEL, PLLC. Chung, Malhas & Mantel ®2013 Copyright © 2013 by Chung, Malhas & Mantel, PLLC. All rights reserved. No part of this booklet may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without written permission from Chung, Malhas & Mantel, PLLC. No copyright claim on U.S. government material. Request for permission to make electronic or print copies of any part of this booklet should be mailed to Chung, Malhas & Mantel, PLLC, 600 First Avenue, Suite 400, Seattle, Washington 98104 or e-mailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents THE PARTNERS iii FOREWORD v PREFACE vi CHAPTER I. Immigrant – EB-5 Investor Program (Green Card) Overview 1 EB-5 Immigrant Investment Flowchart 2 Steps to Qualify Under the EB-5 Program 3 EB-5 Requirements 3 EB-5 Program Benefits 4 Benefits of Immigrating to the United States 4 Ways to Invest Through EB-5 5 Industry Investment Areas 6 EB-5 Fee Structure 7 EB-5 Statistics 8 CHAPTER II. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

Wood County – March 9Th, 2018 Preliminary Report

Nourishing Networks Workshop Wood County – March 9th, 2018 Preliminary Report 0 Nourishing Networks Wood County: Workshop Reflections and Report Authors: Dr. Bradley R. Wilson, Director, Food Justice Lab Heidi Gum, Coordinator, Nourishing Networks Program Facilitators: Dr. Bradley Wilson, Food Justice Lab Director Jessica Arnold, Community Food Initiatives Jed DeBruin, Food Justice Fellow Kelly Fernandez, Community Food Initiatives Thomson Gross, Food Justice Lab GIS Research Director Heidi Gum, Nourishing Networks Coordinator Joshua Lohnes, Food Justice Fellow Amanda Marple, Food Justice Fellow Ashley Reece, Food Justice Laboratory VISTA Raina Schoonover, Community Food Initiatives Participants: Amy Arnold - United Way Alliance of the MOV Sister Molly Bauer - Sisters Health Foundation Judith Boston - Fairlawn Baptist Church Food Pantry and Wood County Emergency Food Co-op Andy Church – United Way Alliance of the MOV Marian Clowes - Parkersburg Area Community Foundation and Regional Affiliates Kristy Cramlet - Highmark Health Gwen Crum - WVU Wood County Extension (continued on next page) 1 Dianne Davis - Lynn Street Church of Christ Laura Dean – Mt. Pleasant Food Pantry Lisa Doyle-Parsons - Circles Campaign of the Mid-Ohio Valley Kayla Ersch - Community Resources Inc. Amy Gherke - The Salvation Army Shirley Grogg - The Salvation Army Sara Hess - United Way Alliance of the MOV Kayla Hinkley - Try This WV Sherry Hinton - Sak Pak Delaney Laughery - United Way Alliance of the MOV Jeremy Lessner - Catholic Charities of WV Andrew Mayle - Mid-Ohio