Circle Theorems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

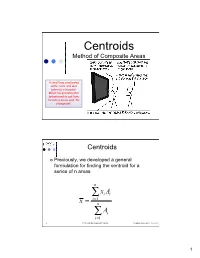

Centroids by Composite Areas.Pptx

Centroids Method of Composite Areas A small boy swallowed some coins and was taken to a hospital. When his grandmother telephoned to ask how he was a nurse said 'No change yet'. Centroids ¢ Previously, we developed a general formulation for finding the centroid for a series of n areas n xA ∑ ii i=1 x = n A ∑ i i=1 2 Centroids by Composite Areas Monday, November 12, 2012 1 Centroids ¢ xi was the distance from the y-axis to the local centroid of the area Ai n xA ∑ ii i=1 x = n A ∑ i i=1 3 Centroids by Composite Areas Monday, November 12, 2012 Centroids ¢ If we can break up a shape into a series of smaller shapes that have predefined local centroid locations, we can use this formula to locate the centroid of the composite shape n xA ∑ ii i=1 x = n A ∑ i 4 Centroids by Composite Areas i=1 Monday, November 12, 2012 2 Centroid by Composite Bodies ¢ There is a table in the back cover of your book that gives you the location of local centroids for a select group of shapes ¢ The point labeled C is the location of the centroid of that shape. 5 Centroids by Composite Areas Monday, November 12, 2012 Centroid by Composite Bodies ¢ Please note that these are local centroids, they are given in reference to the x and y axes as shown in the table. 6 Centroids by Composite Areas Monday, November 12, 2012 3 Centroid by Composite Bodies ¢ For example, the centroid location of the semicircular area has the y-axis through the center of the area and the x-axis at the bottom of the area ¢ The x-centroid would be located at 0 and the y-centroid would be located -

Circle Theorems

Circle theorems A LEVEL LINKS Scheme of work: 2b. Circles – equation of a circle, geometric problems on a grid Key points • A chord is a straight line joining two points on the circumference of a circle. So AB is a chord. • A tangent is a straight line that touches the circumference of a circle at only one point. The angle between a tangent and the radius is 90°. • Two tangents on a circle that meet at a point outside the circle are equal in length. So AC = BC. • The angle in a semicircle is a right angle. So angle ABC = 90°. • When two angles are subtended by the same arc, the angle at the centre of a circle is twice the angle at the circumference. So angle AOB = 2 × angle ACB. • Angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal. This means that angles in the same segment are equal. So angle ACB = angle ADB and angle CAD = angle CBD. • A cyclic quadrilateral is a quadrilateral with all four vertices on the circumference of a circle. Opposite angles in a cyclic quadrilateral total 180°. So x + y = 180° and p + q = 180°. • The angle between a tangent and chord is equal to the angle in the alternate segment, this is known as the alternate segment theorem. So angle BAT = angle ACB. Examples Example 1 Work out the size of each angle marked with a letter. Give reasons for your answers. Angle a = 360° − 92° 1 The angles in a full turn total 360°. = 268° as the angles in a full turn total 360°. -

20. Geometry of the Circle (SC)

20. GEOMETRY OF THE CIRCLE PARTS OF THE CIRCLE Segments When we speak of a circle we may be referring to the plane figure itself or the boundary of the shape, called the circumference. In solving problems involving the circle, we must be familiar with several theorems. In order to understand these theorems, we review the names given to parts of a circle. Diameter and chord The region that is encompassed between an arc and a chord is called a segment. The region between the chord and the minor arc is called the minor segment. The region between the chord and the major arc is called the major segment. If the chord is a diameter, then both segments are equal and are called semi-circles. The straight line joining any two points on the circle is called a chord. Sectors A diameter is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. It is, therefore, the longest possible chord of a circle. In the diagram, O is the center of the circle, AB is a diameter and PQ is also a chord. Arcs The region that is enclosed by any two radii and an arc is called a sector. If the region is bounded by the two radii and a minor arc, then it is called the minor sector. www.faspassmaths.comIf the region is bounded by two radii and the major arc, it is called the major sector. An arc of a circle is the part of the circumference of the circle that is cut off by a chord. -

Foundations of Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Foundations of geometry Lawrence Michael Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Lawrence Michael, "Foundations of geometry" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3419 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Approved by: 3)?/08 Murran, Committee Chair Date _ ommi^yee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member 1 Peter Williams, Chair, Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics iii Abstract In this paper, a brief introduction to the history, and development, of Euclidean Geometry will be followed by a biographical background of David Hilbert, highlighting significant events in his educational and professional life. In an attempt to add rigor to the presentation of Geometry, Hilbert defined concepts and presented five groups of axioms that were mutually independent yet compatible, including introducing axioms of congruence in order to present displacement. -

Archimedes and the Arbelos1 Bobby Hanson October 17, 2007

Archimedes and the Arbelos1 Bobby Hanson October 17, 2007 The mathematician’s patterns, like the painter’s or the poet’s must be beautiful; the ideas like the colours or the words, must fit together in a harmonious way. Beauty is the first test: there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics. — G.H. Hardy, A Mathematician’s Apology ACBr 1 − r Figure 1. The Arbelos Problem 1. We will warm up on an easy problem: Show that traveling from A to B along the big semicircle is the same distance as traveling from A to B by way of C along the two smaller semicircles. Proof. The arc from A to C has length πr/2. The arc from C to B has length π(1 − r)/2. The arc from A to B has length π/2. ˜ 1My notes are shamelessly stolen from notes by Tom Rike, of the Berkeley Math Circle available at http://mathcircle.berkeley.edu/BMC6/ps0506/ArbelosBMC.pdf . 1 2 If we draw the line tangent to the two smaller semicircles, it must be perpendicular to AB. (Why?) We will let D be the point where this line intersects the largest of the semicircles; X and Y will indicate the points of intersection with the line segments AD and BD with the two smaller semicircles respectively (see Figure 2). Finally, let P be the point where XY and CD intersect. D X P Y ACBr 1 − r Figure 2 Problem 2. Now show that XY and CD are the same length, and that they bisect each other. -

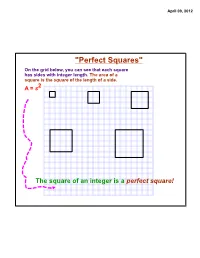

"Perfect Squares" on the Grid Below, You Can See That Each Square Has Sides with Integer Length

April 09, 2012 "Perfect Squares" On the grid below, you can see that each square has sides with integer length. The area of a square is the square of the length of a side. A = s2 The square of an integer is a perfect square! April 09, 2012 Square Roots and Irrational Numbers The inverse of squaring a number is finding a square root. The square-root radical, , indicates the nonnegative square root of a number. The number underneath the square root (radical) sign is called the radicand. Ex: 16 = 121 = 49 = 144 = The square of an integer results in a perfect square. Since squaring a number is multiplying it by itself, there are two integer values that will result in the same perfect square: the positive integer and its opposite. 2 Ex: If x = (perfect square), solutions would be x and (-x)!! Ex: a2 = 25 5 and -5 would make this equation true! April 09, 2012 If an integer is NOT a perfect square, its square root is irrational!!! Remember that an irrational number has a decimal form that is non- terminating, non-repeating, and thus cannot be written as a fraction. For an integer that is not a perfect square, you can estimate its square root on a number line. Ex: 8 Since 22 = 4, and 32 = 9, 8 would fall between integers 2 and 3 on a number line. -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 April 09, 2012 Approximate where √40 falls on the number line: Approximate where √192 falls on the number line: April 09, 2012 Topic Extension: Simplest Radical Form Simplify the radicand so that it has no more perfect-square factors. -

Lesson 20: Composite Area Problems

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 20 7•3 Lesson 20: Composite Area Problems Student Outcomes . Students find the area of regions in the coordinate plane with polygonal boundaries by decomposing the plane into triangles and quadrilaterals, including regions with polygonal holes. Students find composite areas of regions in the coordinate plane by decomposing the plane into familiar figures (triangles, quadrilaterals, circles, semicircles, and quarter circles). Lesson Notes In Lessons 17 through 20, students learned to find the areas of various regions, including quadrilaterals, triangles, circles, semicircles, and those plotted on coordinate planes. In this lesson, students use prior knowledge to use the sum and/or difference of the areas to find unknown composite areas. Classwork Example 1 (5 minutes) Scaffolding: For struggling students, display Example 1 posters around the room displaying the visuals and the Find the composite area of the shaded region. Use ퟑ. ퟏퟒ for 흅. formulas of the area of a circle, a triangle, and a quadrilateral for reference. Allow students to look at the problem and find the area independently before solving as a class. What information can we take from the image? Two circles are on the coordinate plane. The diameter of the larger circle is 6 units, and the diameter of MP.1 the smaller circle is 4 units. How do we know what the diameters of the circles are? We can count the units along the diameter of the circles, or we can subtract the coordinate points to find the length of the diameter. Lesson 20: Composite Area Problems 283 This work is derived from Eureka Math ™ and licensed by Great Minds. -

Chapter 6 the Arbelos

Chapter 6 The arbelos 6.1 Archimedes’ theorems on the arbelos Theorem 6.1 (Archimedes 1). The two circles touching CP on different sides and AC CB each touching two of the semicircles have equal diameters AB· . P W1 W2 A O1 O C O2 B A O1 O C O2 B Theorem 6.2 (Archimedes 2). The diameter of the circle tangent to all three semi- circles is AC CB AB · · . AC2 + AC CB + CB2 · We shall consider Theorem ?? in ?? later, and for now examine Archimedes’ wonderful proofs of the more remarkable§ Theorems 6.1 and 6.2. By synthetic reasoning, he computed the radii of these circles. 1Book of Lemmas, Proposition 5. 2Book of Lemmas, Proposition 6. 602 The arbelos 6.1.1 Archimedes’ proof of the twin circles theorem In the beginning of the Book of Lemmas, Archimedes has established a basic proposition 3 on parallel diameters of two tangent circles. If two circles are tangent to each other (internally or externally) at a point P , and if AB, XY are two parallel diameters of the circles, then the lines AX and BY intersect at P . D F I W1 E H W2 G A O C B Figure 6.1: Consider the circle tangent to CP at E, and to the semicircle on AC at G, to that on AB at F . If EH is the diameter through E, then AH and BE intersect at F . Also, AE and CH intersect at G. Let I be the intersection of AE with the outer semicircle. Extend AF and BI to intersect at D. -

Points, Lines, and Planes a Point Is a Position in Space. a Point Has No Length Or Width Or Thickness

Points, Lines, and Planes A Point is a position in space. A point has no length or width or thickness. A point in geometry is represented by a dot. To name a point, we usually use a (capital) letter. A A (straight) line has length but no width or thickness. A line is understood to extend indefinitely to both sides. It does not have a beginning or end. A B C D A line consists of infinitely many points. The four points A, B, C, D are all on the same line. Postulate: Two points determine a line. We name a line by using any two points on the line, so the above line can be named as any of the following: ! ! ! ! ! AB BC AC AD CD Any three or more points that are on the same line are called colinear points. In the above, points A; B; C; D are all colinear. A Ray is part of a line that has a beginning point, and extends indefinitely to one direction. A B C D A ray is named by using its beginning point with another point it contains. −! −! −−! −−! In the above, ray AB is the same ray as AC or AD. But ray BD is not the same −−! ray as AD. A (line) segment is a finite part of a line between two points, called its end points. A segment has a finite length. A B C D B C In the above, segment AD is not the same as segment BC Segment Addition Postulate: In a line segment, if points A; B; C are colinear and point B is between point A and point C, then AB + BC = AC You may look at the plus sign, +, as adding the length of the segments as numbers. -

Foundations for Geometry

Foundations for Geometry 1A Euclidean and Construction Tools 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lab Explore Properties Associated with Points 1-2 Measuring and Constructing Segments 1-3 Measuring and Constructing Angles 1-4 Pairs of Angles 1B Coordinate and Transformation Tools 1-5 Using Formulas in Geometry 1-6 Midpoint and Distance in the Coordinate Plane 1-7 Transformations in the Coordinate Plane Lab Explore Transformations KEYWORD: MG7 ChProj Representations of points, lines, and planes can be seen in the Los Angeles skyline. Skyline Los Angeles, CA 2 Chapter 1 Vocabulary Match each term on the left with a definition on the right. 1. coordinate A. a mathematical phrase that contains operations, numbers, and/or variables 2. metric system of measurement B. the measurement system often used in the United States 3. expression C. one of the numbers of an ordered pair that locates a point on a coordinate graph 4. order of operations D. a list of rules for evaluating expressions E. a decimal system of weights and measures that is used universally in science and commonly throughout the world Measure with Customary and Metric Units For each object tell which is the better measurement. 5. length of an unsharpened pencil 6. the diameter of a quarter __1 __3 __1 7 2 in. or 9 4 in. 1 m or 2 2 cm 7. length of a soccer field 8. height of a classroom 100 yd or 40 yd 5 ft or 10 ft 9. height of a student’s desk 10. length of a dollar bill 30 in. -

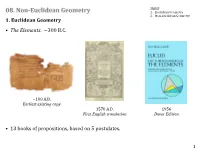

08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1

Topics: 08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1. Euclidean Geometry 2. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1. Euclidean Geometry • The Elements. ~300 B.C. ~100 A.D. Earliest existing copy 1570 A.D. 1956 First English translation Dover Edition • 13 books of propositions, based on 5 postulates. 1 Euclid's 5 Postulates 1. A straight line can be drawn from any point to any point. • • A B 2. A finite straight line can be produced continuously in a straight line. • • A B 3. A circle may be described with any center and distance. • 4. All right angles are equal to one another. 2 5. If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side together less than two right angles, then the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles are together less than two right angles. � � • � + � < 180∘ • Euclid's Accomplishment: showed that all geometric claims then known follow from these 5 postulates. • Is 5th Postulate necessary? (1st cent.-19th cent.) • Basic strategy: Attempt to show that replacing 5th Postulate with alternative leads to contradiction. 3 • Equivalent to 5th Postulate (Playfair 1795): 5'. Through a given point, exactly one line can be drawn parallel to a given John Playfair (1748-1819) line (that does not contain the point). • Parallel straight lines are straight lines which, being in the same plane and being • Only two logically possible alternatives: produced indefinitely in either direction, do not meet one 5none. Through a given point, no lines can another in either direction. (The Elements: Book I, Def. -

Different Types of Loading on Right Angle Joints

HIGH STRENGTH RIGHT ANGLE COMPOSITE JOINTS FOR CIVIL ENGINEERING APPLICATIONS Gerard M Van Erp, Fibre Composites Design and Development (FCDD), University of Southern Queensland (USQ), Toowoomba, Queensland, 4350, Australia, SUMMARY: This paper presents initial results of an ongoing research project that is concerned with the development of strong right angle composite joints for civil engineering applications. Experimental, analytical and numerical results for four different types of monocoque right angle joints loaded in pure bending will be presented. It will be shown that a significant increase in load carrying capacity can be obtained through small changes to the inside corner of the joints. The test results also demonstrate that there is reasonable correlation between the failure mode of the joints and the location and severity of the stress concentrations predicted by the FE method. KEYWORDS: Joining, Civil Application, Testing, Structures. INTRODUCTION Plane frames are common load carrying elements in buildings and civil engineering structures. These frames are combinations of beams and columns, rigidly jointed at right angles. The rigid joints transfer forces and moments between the horizontal and the vertical members (Fig. 1a) and play a major role in resisting lateral loads (Fig. 1b). Figure 1a: Frame subjected to vertical loading b: Frame subjected to horizontal loading Figure 1c: Different types of loading on right angle joints Depending on the type of loading and on the location of the joint in the frame, the joint will be subjected to a closing action (Fig. 1: case A and B) or an opening action (Fig. 1: case C). This paper will concentrate on joints with an opening action only.