Foundations of Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circle Theorems

Circle theorems A LEVEL LINKS Scheme of work: 2b. Circles – equation of a circle, geometric problems on a grid Key points • A chord is a straight line joining two points on the circumference of a circle. So AB is a chord. • A tangent is a straight line that touches the circumference of a circle at only one point. The angle between a tangent and the radius is 90°. • Two tangents on a circle that meet at a point outside the circle are equal in length. So AC = BC. • The angle in a semicircle is a right angle. So angle ABC = 90°. • When two angles are subtended by the same arc, the angle at the centre of a circle is twice the angle at the circumference. So angle AOB = 2 × angle ACB. • Angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal. This means that angles in the same segment are equal. So angle ACB = angle ADB and angle CAD = angle CBD. • A cyclic quadrilateral is a quadrilateral with all four vertices on the circumference of a circle. Opposite angles in a cyclic quadrilateral total 180°. So x + y = 180° and p + q = 180°. • The angle between a tangent and chord is equal to the angle in the alternate segment, this is known as the alternate segment theorem. So angle BAT = angle ACB. Examples Example 1 Work out the size of each angle marked with a letter. Give reasons for your answers. Angle a = 360° − 92° 1 The angles in a full turn total 360°. = 268° as the angles in a full turn total 360°. -

David Hilbert's Contributions to Logical Theory

David Hilbert’s contributions to logical theory CURTIS FRANKS 1. A mathematician’s cast of mind Charles Sanders Peirce famously declared that “no two things could be more directly opposite than the cast of mind of the logician and that of the mathematician” (Peirce 1976, p. 595), and one who would take his word for it could only ascribe to David Hilbert that mindset opposed to the thought of his contemporaries, Frege, Gentzen, Godel,¨ Heyting, Łukasiewicz, and Skolem. They were the logicians par excellence of a generation that saw Hilbert seated at the helm of German mathematical research. Of Hilbert’s numerous scientific achievements, not one properly belongs to the domain of logic. In fact several of the great logical discoveries of the 20th century revealed deep errors in Hilbert’s intuitions—exemplifying, one might say, Peirce’s bald generalization. Yet to Peirce’s addendum that “[i]t is almost inconceivable that a man should be great in both ways” (Ibid.), Hilbert stands as perhaps history’s principle counter-example. It is to Hilbert that we owe the fundamental ideas and goals (indeed, even the name) of proof theory, the first systematic development and application of the methods (even if the field would be named only half a century later) of model theory, and the statement of the first definitive problem in recursion theory. And he did more. Beyond giving shape to the various sub-disciplines of modern logic, Hilbert brought them each under the umbrella of mainstream mathematical activity, so that for the first time in history teams of researchers shared a common sense of logic’s open problems, key concepts, and central techniques. -

20. Geometry of the Circle (SC)

20. GEOMETRY OF THE CIRCLE PARTS OF THE CIRCLE Segments When we speak of a circle we may be referring to the plane figure itself or the boundary of the shape, called the circumference. In solving problems involving the circle, we must be familiar with several theorems. In order to understand these theorems, we review the names given to parts of a circle. Diameter and chord The region that is encompassed between an arc and a chord is called a segment. The region between the chord and the minor arc is called the minor segment. The region between the chord and the major arc is called the major segment. If the chord is a diameter, then both segments are equal and are called semi-circles. The straight line joining any two points on the circle is called a chord. Sectors A diameter is a chord that passes through the center of the circle. It is, therefore, the longest possible chord of a circle. In the diagram, O is the center of the circle, AB is a diameter and PQ is also a chord. Arcs The region that is enclosed by any two radii and an arc is called a sector. If the region is bounded by the two radii and a minor arc, then it is called the minor sector. www.faspassmaths.comIf the region is bounded by two radii and the major arc, it is called the major sector. An arc of a circle is the part of the circumference of the circle that is cut off by a chord. -

Old and New Results in the Foundations of Elementary Plane Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries Marvin Jay Greenberg

Old and New Results in the Foundations of Elementary Plane Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries Marvin Jay Greenberg By “elementary” plane geometry I mean the geometry of lines and circles—straight- edge and compass constructions—in both Euclidean and non-Euclidean planes. An axiomatic description of it is in Sections 1.1, 1.2, and 1.6. This survey highlights some foundational history and some interesting recent discoveries that deserve to be better known, such as the hierarchies of axiom systems, Aristotle’s axiom as a “missing link,” Bolyai’s discovery—proved and generalized by William Jagy—of the relationship of “circle-squaring” in a hyperbolic plane to Fermat primes, the undecidability, incom- pleteness, and consistency of elementary Euclidean geometry, and much more. A main theme is what Hilbert called “the purity of methods of proof,” exemplified in his and his early twentieth century successors’ works on foundations of geometry. 1. AXIOMATIC DEVELOPMENT 1.0. Viewpoint. Euclid’s Elements was the first axiomatic presentation of mathemat- ics, based on his five postulates plus his “common notions.” It wasn’t until the end of the nineteenth century that rigorous revisions of Euclid’s axiomatics were presented, filling in the many gaps in his definitions and proofs. The revision with the great- est influence was that by David Hilbert starting in 1899, which will be discussed below. Hilbert not only made Euclid’s geometry rigorous, he investigated the min- imal assumptions needed to prove Euclid’s results, he showed the independence of some of his own axioms from the others, he presented unusual models to show certain statements unprovable from others, and in subsequent editions he explored in his ap- pendices many other interesting topics, including his foundation for plane hyperbolic geometry without bringing in real numbers. -

Foundations of Geometry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2008 Foundations of geometry Lawrence Michael Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Lawrence Michael, "Foundations of geometry" (2008). Theses Digitization Project. 3419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3419 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Mathematics by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Foundations of Geometry A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Lawrence Michael Clarke March 2008 Approved by: 3)?/08 Murran, Committee Chair Date _ ommi^yee Member Susan Addington, Committee Member 1 Peter Williams, Chair, Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics iii Abstract In this paper, a brief introduction to the history, and development, of Euclidean Geometry will be followed by a biographical background of David Hilbert, highlighting significant events in his educational and professional life. In an attempt to add rigor to the presentation of Geometry, Hilbert defined concepts and presented five groups of axioms that were mutually independent yet compatible, including introducing axioms of congruence in order to present displacement. -

Mechanism, Mentalism, and Metamathematics Synthese Library

MECHANISM, MENTALISM, AND METAMATHEMATICS SYNTHESE LIBRARY STUDIES IN EPISTEMOLOGY, LOGIC, METHODOLOGY, AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE Managing Editor: JAAKKO HINTIKKA, Florida State University Editors: ROBER T S. COHEN, Boston University DONALD DAVIDSON, University o/Chicago GABRIEL NUCHELMANS, University 0/ Leyden WESLEY C. SALMON, University 0/ Arizona VOLUME 137 JUDSON CHAMBERS WEBB Boston University. Dept. 0/ Philosophy. Boston. Mass .• U.S.A. MECHANISM, MENT ALISM, AND MET AMA THEMA TICS An Essay on Finitism i Springer-Science+Business Media, B.V. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Webb, Judson Chambers, 1936- CII:J Mechanism, mentalism, and metamathematics. (Synthese library; v. 137) Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Metamathematics. I. Title. QA9.8.w4 510: 1 79-27819 ISBN 978-90-481-8357-9 ISBN 978-94-015-7653-6 (eBook) DOl 10.1007/978-94-015-7653-6 All Rights Reserved Copyright © 1980 by Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht Originally published by D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, Holland in 1980. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1980 No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any informational storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE vii INTRODUCTION ix CHAPTER I / MECHANISM: SOME HISTORICAL NOTES I. Machines and Demons 2. Machines and Men 17 3. Machines, Arithmetic, and Logic 22 CHAPTER II / MIND, NUMBER, AND THE INFINITE 33 I. The Obligations of Infinity 33 2. Mind and Philosophy of Number 40 3. Dedekind's Theory of Arithmetic 46 4. -

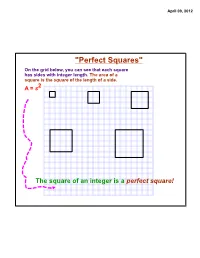

"Perfect Squares" on the Grid Below, You Can See That Each Square Has Sides with Integer Length

April 09, 2012 "Perfect Squares" On the grid below, you can see that each square has sides with integer length. The area of a square is the square of the length of a side. A = s2 The square of an integer is a perfect square! April 09, 2012 Square Roots and Irrational Numbers The inverse of squaring a number is finding a square root. The square-root radical, , indicates the nonnegative square root of a number. The number underneath the square root (radical) sign is called the radicand. Ex: 16 = 121 = 49 = 144 = The square of an integer results in a perfect square. Since squaring a number is multiplying it by itself, there are two integer values that will result in the same perfect square: the positive integer and its opposite. 2 Ex: If x = (perfect square), solutions would be x and (-x)!! Ex: a2 = 25 5 and -5 would make this equation true! April 09, 2012 If an integer is NOT a perfect square, its square root is irrational!!! Remember that an irrational number has a decimal form that is non- terminating, non-repeating, and thus cannot be written as a fraction. For an integer that is not a perfect square, you can estimate its square root on a number line. Ex: 8 Since 22 = 4, and 32 = 9, 8 would fall between integers 2 and 3 on a number line. -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 April 09, 2012 Approximate where √40 falls on the number line: Approximate where √192 falls on the number line: April 09, 2012 Topic Extension: Simplest Radical Form Simplify the radicand so that it has no more perfect-square factors. -

Definitions and Nondefinability in Geometry 475 2

Definitions and Nondefinability in Geometry1 James T. Smith Abstract. Around 1900 some noted mathematicians published works developing geometry from its very beginning. They wanted to supplant approaches, based on Euclid’s, which han- dled some basic concepts awkwardly and imprecisely. They would introduce precision re- quired for generalization and application to new, delicate problems in higher mathematics. Their work was controversial: they departed from tradition, criticized standards of rigor, and addressed fundamental questions in philosophy. This paper follows the problem, Which geo- metric concepts are most elementary? It describes a false start, some successful solutions, and an argument that one of those is optimal. It’s about axioms, definitions, and definability, and emphasizes contributions of Mario Pieri (1860–1913) and Alfred Tarski (1901–1983). By fol- lowing this thread of ideas and personalities to the present, the author hopes to kindle interest in a fascinating research area and an exciting era in the history of mathematics. 1. INTRODUCTION. Around 1900 several noted mathematicians published major works on a subject familiar to us from school: developing geometry from the very beginning. They wanted to supplant the established approaches, which were based on Euclid’s, but which handled awkwardly and imprecisely some concepts that Euclid did not treat fully. They would present geometry with the precision required for general- ization and applications to new, delicate problems in higher mathematics—precision beyond the norm for most elementary classes. Work in this area was controversial: these mathematicians departed from tradition, criticized previous standards of rigor, and addressed fundamental questions in logic and philosophy of mathematics.2 After establishing background, this paper tells a story about research into the ques- tion, Which geometric concepts are most elementary? It describes a false start, some successful solutions, and a demonstration that one of those is in a sense optimal. -

Points, Lines, and Planes a Point Is a Position in Space. a Point Has No Length Or Width Or Thickness

Points, Lines, and Planes A Point is a position in space. A point has no length or width or thickness. A point in geometry is represented by a dot. To name a point, we usually use a (capital) letter. A A (straight) line has length but no width or thickness. A line is understood to extend indefinitely to both sides. It does not have a beginning or end. A B C D A line consists of infinitely many points. The four points A, B, C, D are all on the same line. Postulate: Two points determine a line. We name a line by using any two points on the line, so the above line can be named as any of the following: ! ! ! ! ! AB BC AC AD CD Any three or more points that are on the same line are called colinear points. In the above, points A; B; C; D are all colinear. A Ray is part of a line that has a beginning point, and extends indefinitely to one direction. A B C D A ray is named by using its beginning point with another point it contains. −! −! −−! −−! In the above, ray AB is the same ray as AC or AD. But ray BD is not the same −−! ray as AD. A (line) segment is a finite part of a line between two points, called its end points. A segment has a finite length. A B C D B C In the above, segment AD is not the same as segment BC Segment Addition Postulate: In a line segment, if points A; B; C are colinear and point B is between point A and point C, then AB + BC = AC You may look at the plus sign, +, as adding the length of the segments as numbers. -

Foundations for Geometry

Foundations for Geometry 1A Euclidean and Construction Tools 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lab Explore Properties Associated with Points 1-2 Measuring and Constructing Segments 1-3 Measuring and Constructing Angles 1-4 Pairs of Angles 1B Coordinate and Transformation Tools 1-5 Using Formulas in Geometry 1-6 Midpoint and Distance in the Coordinate Plane 1-7 Transformations in the Coordinate Plane Lab Explore Transformations KEYWORD: MG7 ChProj Representations of points, lines, and planes can be seen in the Los Angeles skyline. Skyline Los Angeles, CA 2 Chapter 1 Vocabulary Match each term on the left with a definition on the right. 1. coordinate A. a mathematical phrase that contains operations, numbers, and/or variables 2. metric system of measurement B. the measurement system often used in the United States 3. expression C. one of the numbers of an ordered pair that locates a point on a coordinate graph 4. order of operations D. a list of rules for evaluating expressions E. a decimal system of weights and measures that is used universally in science and commonly throughout the world Measure with Customary and Metric Units For each object tell which is the better measurement. 5. length of an unsharpened pencil 6. the diameter of a quarter __1 __3 __1 7 2 in. or 9 4 in. 1 m or 2 2 cm 7. length of a soccer field 8. height of a classroom 100 yd or 40 yd 5 ft or 10 ft 9. height of a student’s desk 10. length of a dollar bill 30 in. -

The Foundations of Geometry

The Foundations of Geometry Gerard A. Venema Department of Mathematics and Statistics Calvin College SUB Gottingen 7 219 059 926 2006 A 7409 PEARSON Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458 Contents Preface ix Euclid's Elements 1 1.1 Geometry before Euclid 1 1.2 The logical structure of Euclid's Elements 2 1.3 The historical importance of Euclid's Elements 3 1.4 A look at Book I of the Elements 5 1.5 A critique of Euclid's Elements 8 1.6 Final observations about the Elements 11 Axiomatic Systems and Incidence Geometry 17 2.1 Undefined and defined terms 17 2.2 Axioms 18° 2.3 Theorems 18 2.4 Models 19 2.5 An example of an axiomatic system 19 2.6 The parallel postulates 25 2.7 Axiomatic systems and the real world 27 Theorems, Proofs, and Logic 31 3.1 The place of proof in mathematics 31 3.2 Mathematical language 32 3.3 Stating theorems 34 3.4 Writing proofs 37 3.5 Indirect proof \. 39 3.6 The theorems of incidence geometry ';, . 40 Set Notation and the Real Numbers 43 4.1 Some elementary set theory 43 4.2 Properties of the real numbers 45 4.3 Functions ,48 4.4 The foundations of mathematics 49 The Axioms of Plane Geometry 52 5.1 Systems of axioms for geometry 53 5.2 The undefined terms 56 5.3 Existence and incidence 56 5.4 Distance 57 5.5 Plane separation 63 5.6 Angle measure 67 vi Contents 5.7 Betweenness and the Crossbar Theorem 70 5.8 Side-Angle-Side 84 5.9 The parallel postulates 89 5.10 Models 90 6 Neutral Geometry 94 6.1 Geometry without the parallel postulate 94 6.2 Angle-Side-Angle and its consequences 95 6.3 The Exterior -

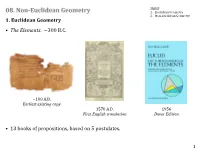

08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1

Topics: 08. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1. Euclidean Geometry 2. Non-Euclidean Geometry 1. Euclidean Geometry • The Elements. ~300 B.C. ~100 A.D. Earliest existing copy 1570 A.D. 1956 First English translation Dover Edition • 13 books of propositions, based on 5 postulates. 1 Euclid's 5 Postulates 1. A straight line can be drawn from any point to any point. • • A B 2. A finite straight line can be produced continuously in a straight line. • • A B 3. A circle may be described with any center and distance. • 4. All right angles are equal to one another. 2 5. If a straight line falling on two straight lines makes the interior angles on the same side together less than two right angles, then the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles are together less than two right angles. � � • � + � < 180∘ • Euclid's Accomplishment: showed that all geometric claims then known follow from these 5 postulates. • Is 5th Postulate necessary? (1st cent.-19th cent.) • Basic strategy: Attempt to show that replacing 5th Postulate with alternative leads to contradiction. 3 • Equivalent to 5th Postulate (Playfair 1795): 5'. Through a given point, exactly one line can be drawn parallel to a given John Playfair (1748-1819) line (that does not contain the point). • Parallel straight lines are straight lines which, being in the same plane and being • Only two logically possible alternatives: produced indefinitely in either direction, do not meet one 5none. Through a given point, no lines can another in either direction. (The Elements: Book I, Def.