Henry Abramson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

®V ®V ®V ®V ®V

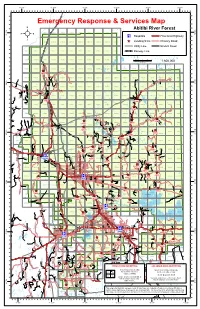

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 82°0'W 81°30'W 81°0'W 80°30'W 80°0'W 79°30'W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N ' N ' 0 0 3 ° 3 ! ° 450559 460559 470559 480559 490559 500559 510559 520559 530559 0 0 5 5 ! v® Hospitals Provincial Highway ! ² 450558 460558 470558 480558 490558 500558 510558 520558 530558 ^_ Landing Sites Primary Road ! ! ! ! Utility Line Branch Road 430557 440557 450! 557 460557 470557 480557 490557 500557 510557 520557 530557 Railway Line ! ! 430556 440556 450556 460556 470556 480556 490556 500556 510556 520556 530556 5 2.5 0 5 10 15 ! Kilometers 1:800,000 ! ! ! ! 45! 0! 555 430555 440555 460555 470555 480555 490555 500555 510555 520555 530555 540555 550555 560555 570555 580555 590555 600555 ! ad ! ! o ^_ e R ak y L dre ! P u ! A O ! it t 6 t 1 e r o 430554 440554 450554 460554 470554 480554 490554 500554 510554 520554 530554 540554 550554 560554 570554 580554 590554 600554 r R R d! o ! d a y ! a ad a p H d o N i ' N o d R ' 0 ! s e R n ° 0 i 1 ° ! R M 0 h r d ! ! 0 u c o 5 Flatt Ext a to red ! F a a 5 e o e d D 4 R ! B 1 430553 440553 45055! 3 460553 470553 480553 490553 500553 510553 520553 530553 540553 550553 560553 570553 580553 590553 600553 R ! ! S C ! ! Li ttle d L Newpost Road ! a o ! ng ! o d R ! o R a a o d e ! R ! s C ! o e ! ! L 450552! ! g k i 430552 440552 ! 460552 470552 480552 490552 500552 510552 520552 530552 540552 550552 560552 570552 580552 590552 600552 C a 0 e ! n ! L U n S 1 i o ! ! ! R y p L ! N a p l ! y 8 C e e ^_ ! r k ^_ K C ! o ! S ! ! R a m t ! 8 ! t ! ! ! S a ! ! ! w ! ! 550551 a ! 430551 440551 450551 -

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit

POPULATION PROFILE 2006 Census Porcupine Health Unit Kapuskasing Iroquois Falls Hearst Timmins Porcupine Cochrane Moosonee Hornepayne Matheson Smooth Rock Falls Population Profile Foyez Haque, MBBS, MHSc Public Health Epidemiologist published by: Th e Porcupine Health Unit Timmins, Ontario October 2009 ©2009 Population Profile - 2006 Census Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude to those without whose support this Population Profile would not be published. First of all, I would like to thank the management committee of the Porcupine Health Unit for their continuous support of and enthusiasm for this publication. Dr. Dennis Hong deserves a special thank you for his thorough revision. Thanks go to Amanda Belisle for her support with editing, creating such a wonderful cover page, layout and promotion of the findings of this publication. I acknowledge the support of the Statistics Canada for history and description of the 2006 Census and also the definitions of the variables. Porcupine Health Unit – 1 Population Profile - 2006 Census 2 – Porcupine Health Unit Population Profile - 2006 Census Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 1 Preface . 5 Executive Summary . 7 A Brief History of the Census in Canada . 9 A Brief Description of the 2006 Census . 11 Population Pyramid. 15 Appendix . 31 Definitions . 35 Table of Charts Table 1: Population distribution . 12 Table 2: Age and gender characteristics. 14 Figure 3: Aboriginal status population . 16 Figure 4: Visible minority . 17 Figure 5: Legal married status. 18 Figure 6: Family characteristics in Ontario . 19 Figure 7: Family characteristics in Porcupine Health Unit area . 19 Figure 8: Low income cut-offs . 20 Figure 11: Mother tongue . -

TOXIC WATER: the KASHECHEWAN STORY Introduction It Was the Straw That Broke the Prover- Had Been Under a Boil-Water Alert on and Focus Bial Camel’S Back

TOXIC WATER: THE KASHECHEWAN STORY Introduction It was the straw that broke the prover- had been under a boil-water alert on and Focus bial camel’s back. A fax arrived from off for years. In fall 2005, Canadi- Health Canada (www.hc-sc.gc.ca) at the A week after the water tested positive ans were stunned to hear of the Kashechewan First Nations council for E. coli, Indian Affairs Minister appalling living office, revealing that E. coli had been Andy Scott arrived in Kashechewan. He conditions on the detected in the reserve’s drinking water. offered to provide the people with more Kashechewan First Enough was enough. A community bottled water but little else. Incensed by Nations Reserve in already plagued by poverty and unem- Scott’s apparent indifference, the Northern Ontario. ployment was now being poisoned by community redoubled their efforts, Initial reports documented the its own water supply. Something putting pressure on the provincial and presence of E. coli needed to be done, and some members federal governments to evacuate those in the reserve’s of the reserve had a plan. First they who were suffering from the effects of drinking water. closed down the schools. Next, they the contaminated water. The Ontario This was followed called a meeting of concerned members government pointed the finger at Ot- by news of poverty and despair, a of the community. Then they launched tawa because the federal government is reflection of a a media campaign that shifted the responsible for Canada’s First Nations. standard of living national spotlight onto the horrendous Ottawa pointed the finger back at the that many thought conditions in this remote, Northern province, saying that water safety and unimaginable in Ontario reserve. -

Five Nations Energy Inc

Five Nations Energy Inc. Presented by: Edward Chilton Secretary/Treasurer And Lucie Edwards Chief Executive Officer Where we are James Bay area of Ontario Some History • Treaty 9 signed in 1905 • Treaty Organization Nishnawbe Aski Nation formed early 1970’s • Mushkegowuk (Tribal) Council formed late 1980’s • 7 First Nations including Attawapiskat, Kashechewan, Fort Albany • Fort Albany very early trading post early 1800’s-Hudson Bay Co. • Attawapiskat historical summer gathering place-permanent community late 1950’s • Kashechewan-some Albany families moved late 1950’s History of Electricity Supply • First energization occurred in Fort Albany- late 1950’s Department of Defense Mid- Canada radar base as part of the Distant Early Warning system installed diesel generators. • Transferred to Catholic Mission mid 1960’s • Distribution system extended to community residents early 1970’s and operated by Ontario Hydro • Low Voltage (8132volts) line built to Kashechewan mid 1970’s, distribution system built and operated by Ontario Hydro • Early 1970’s diesel generation and distribution system built and operated by Ontario Hydro • All based on Electrification agreement between Federal Government and Ontario Provincial Crown Corporation Ontario Hydro Issues with Diesel-Fort Albany Issues with Diesel-Attawapiskat • Fuel Spill on River From Diesel To Grid Based Supply • Early 1970’s - Ontario Hydro Remote Community Systems operated diesel generators in the communities • Federal Government (Indian and Northern Affairs Canada-INAC) covered the cost for -

Appendix a IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (Previously Submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013

Summary of Consultation to Support the Côté Gold Project Closure Plan Côté Gold Project Appendix A IAMGOLD Côté Gold Project Aboriginal Consultation Plan (previously submitted to the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 2013 Stakeholder Consultation Plan (2013) TC180501 | October 2018 CÔTÉ GOLD PROJECT PROVINCIAL INDIVIDUAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROPOSED TERMS OF REFERENCE APPENDIX D PROPOSED STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION PLAN Submitted to: IAMGOLD Corporation 401 Bay Street, Suite 3200 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2Y4 Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, a Division of AMEC Americas Limited 160 Traders Blvd. East, Suite 110 Mississauga, Ontario L4Z 3K7 July 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Provincial EA and Consultation Plan Requirements ........................................... 1-1 1.3 Federal EA and Consultation Plan Requirements .............................................. 1-2 1.4 Responsibility for Plan Implementation .............................................................. 1-3 2.0 CONSULTATION APPROACH ..................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Goals and Objectives ......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Stakeholder Identification .................................................................................. -

Official Road Map of Ontario

o ojikitM L. ik N th W p ercyP L. Pitukupi r a a 14 o k 7 K 8 9 10 11 12 13 N 15 h Stone L. Onakawana w s 88° 87° 86° 85° 84° 83° 82° 81° a fi y k L. r o N c e w v e a i ka J R t Ara L. to C r s Abamasagi e t g g O er iv ic a L. wnin R Riv R m ro iv i D e C e O'Sullivan L R. l r t i R H t it F L. t F Jog L. l L e . ge O Marshall Rid i I R MISSINAIBI m R L. a A Ferland R g T Esnagami N ta a i t O Mud k b R i Wababimiga i a River b L. a i M v a in 50° ive e L. i R r ss A i r 50° Aroland gam River M Coral mb Auden Lower no O Ke r Otter Rapids 643 Twin ive A R b r 19 Nakina N i fe L. t e i Logan I. 9 v b Fleming i A i L. R b r i Upper e a ti Riv k b Onaman is Private road i Twin L. b L. a with public access E iv P Route privée Murchison I. Burrows Chipman à accès public North 584 r fe L. L. e Wind n iv 62 a FUSHIMI LAKE i R L. w r a e Fraserdale s v Pivabiska . -

Smooth Rock Falls Community Profile

Town of Smooth Rock Falls http://www.townofsmoothrockfalls.ca/ V 1.0 February 2016 © 2016 Town of Smooth Rock Falls Information in this document is subject to change without notice. Although all data is believed to be the most accurate and up-to-date, the reader is advised to verify all data before making any decisions based upon the information contained in this document. For further information, please contact: Jason Felix 142 First Street PO Box 249 Smooth Rock Falls, ON P0L 2B0 Phone: 705-338-2036 Fax: 705-338-2007 Web: http://www.townofsmoothrockfalls.ca/ Town of Smooth Rock Falls http://www.townofsmoothrockfalls.ca/ Town of Smooth Rock Falls Asset Inventory & Community Profile Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Location ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Climate .............................................................................................................................. 4 2 DEMOGRAPHICS ........................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Population Size and Growth ................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Age Profile ......................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Language Characteristics -

Service List (As of Decmeber 12, 2019).Pdf

Court File Number: CV-18-601307-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST CRH FUNDING II PTE. LTD. Applicant - and - SAGE GOLD INC. Respondent SERVICE LIST (UPDATED NOVEMBER 20, 2019) GENERAL CRH FUNDING II PTE. LTD. STIKEMAN ELLIOTT LLP 505 Fifth Avenue, 15th Floor 5300 Commerce Court West New York, NY 10017 199 Bay Street USA Toronto, ON M5L 1B9 Guy P. Martel Tel: (514) 397-3163 Email: [email protected] Danny Duy Vu Tel: (514) 397-6495 Email: [email protected] Lee Nicholson Tel: (416) 869-5604 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for CRH Funding II PTE. Ltd. DELOITTE RESTRUCTURING INC. Philip J. Reynolds Bay Adelaide East Tel: (416) 956 9200 8 Adelaide Street West, Suite 200 Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON Todd Ambachtsheer Receiver of Sage Gold Inc. Tel: (416) 607 0781 Email: [email protected] McMILLAN LLP Wael Rostom 181 Bay Street Tel: (416) 865-7790 Suite 4400 Email: [email protected] Brookfield Place Toronto, ON M5J 2T3 Tushara Weerasooriya Email: [email protected] Stephen Brown-Okruhlik Tel: (416) 865-7043 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for the Receiver SAGE GOLD INC. Nigel Lees 67 Yonge Street, Suite 808 President Toronto, ON M5E 1J8 Email: [email protected] ORMSTON LIST FRAWLEY LLP John Ormston 6 Adelaide Street Tel: (416) 800-1151 Suite 500 Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M5C 1H6 Lindsay Moffatt Email: [email protected] Lawyers for Sage Gold Inc. PARTIES WITH SECURITY INTERESTS OR RIGHTS REGISTERED ON THE LAND REGISTRY TOROMONT INDUSTRIES LTD./BATTELEFIELD Pallett Valo LLP EQUIPMENT RENTALS 77 City Centre Drive 1691 Riverside Drive West Tower Timmins, ON P4R 1M4 Suite 300 Mississauga, ON L5B 1M5 Maria Ruberto Tel: (905) 273-3300 Email: [email protected] Neeta Sandhu Email: [email protected] Lawyers for Toromont Industries Ltd./Battlefield Equipment Rentals WLAD & SONS CONSTRUCTION LTD. -

LIVING HOMES for CULTURAL EXPRESSION NMAI EDITIONS SMITHSONIAN Living Homes for Cultural Expression �

LIVING HOMES FOR CULTURAL EXPRESSION NMAIq EDITIONS � living homes � for cultural expression � North American Native Perspectives on Creating Community Museums NMAI EDITIONS SMITHSONIAN National Museum of the American Indian � Smithsonian Institution � Washington, D.C., and New York � living homes for cultural expression � NMAIq EDITIONS � living homes for cultural expression � North American Native Perspectives on Creating Community Museums Karen Coody Cooper & niColasa i. sandoval Editors National Museum of the American Indian � Smithsonian Institution � Washington, D.C., and New York � 2006 � © 2006 Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the Smithsonian Institution and the National Museum of the American Indian. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Living homes for cultural expression : North American Native perspectives on creating community museums / Karen Coody Cooper and Nicolasa I. Sandoval, editors. p. cm. ISBN 0-9719163-8-1 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Museums. 2. Indian arts—United States. 3. Ethnological museums and collections—United States. 4. Minority arts facilities—United States. 5. Community centers—United States. 6. Community development—United States. I. Cooper, Karen Coody. II. Sandoval, Nicolasa I. III. National Museum of the American Indian (U.S.) E56.L58 2005 305.897’0075—dc22 2005016415 Manufactured in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the -

Canadian Charities Giving to Indigenous Charities and Qualified Donees - 2018

CanadianCharitylaw.ca/ RedskyFundraising.com/ Canadian charities giving to Indigenous Charities and Qualified Donees - 2018 By Sharon Redsky, Wanda Brascoupe, Mark Blumberg and Jessie Lang (May 31, 2021) We recently reviewed the T3010 Registered Charity Information Return database for 2018 to see how many gifts and the value of those gifts were made from Canadian registered charities to “Indigenous Charities” and certain Qualified Donees such as First Nation Governments or ‘Bands’ (listed as “municipal or public body performing a function of government in Canada”). Together we refer to them as “Indigenous Groups”. To identify Indigenous Groups, we reviewed the list with all grants over $30,000 and we also used terms and phrases such as: Indigenous, First Nation, Metis, Inuit, Indian, Indian Band, Nation, Tribal council, National Indian Brotherhood, etc.. We also used a list from the Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Fund by CanadaHelps developed by Wanda Brascoupe. We cut off the review at $30,000 because these larger grants are over 28,000 grants and also encompass about 90% of the value of grants made by Canadian charities to qualified donees. If an individual or corporation donates to an Indigenous Group, this would not be reflected in this article as we only have visibility as to registered charities making gifts to other qualified donees. We encourage others to either do a more comprehensive review or use different methodology. 1 CanadianCharitylaw.ca/ RedskyFundraising.com/ We believe that Indigenous led charities are vital in providing culturally appropriate services. There are numerous charities in Canada that are either Indigenous led or primarily serving Indigenous communities, but it is not always easily determinable who they are and how many there are. -

Collège De Hearst 60 9Th Street, Postal Bag 580 Hearst, Ontario P0L 1N0

Collège de Hearst 60 9th Street, Postal Bag 580 Hearst, Ontario P0L 1N0 Background information on the Collège de Hearst 1. Our History The Collège de Hearst is an Ontario public institution whose mandate is university education and research and community involvement. In 1971, it was recognized by the Ontario government as a public academic institution and since then has been included in the list of Ontario universities. As such, the Collège de Hearst receives its funding directly from the province. Founded as the Séminaire de Hearst in 1953, it was incorporated under the name Le Collège de Hearst in 1959 so that it could deliver university education. The business name Collège universitaire de Hearst was adopted in 1972, when it was recognized and funded by the province of Ontario as a public academic institution. At that time, it stopped offering secondary school programs, since they had become accessible throughout the region when the Ontario government established French-language public high schools. From 1953 to 1971, the institution was managed and funded by the Diocese of Hearst. Under affiliation agreements reached with the University of Sudbury in 1957 and Laurentian University of Sudbury in 1963, the programs and degrees of the Collège de Hearst are sanctioned by the Senate of Laurentian University. The agreement with Laurentian University was renegotiated and updated in 1986. Laurentian University supports the present application for consent to use the name “Université de Hearst”. 2. Structure Like every other university in the province, the Collège de Hearst is an independent institution led by a Board of Governors and a Senate. -

Report on the Kashechewan First Nation and Its People

Report on the Kashechewan First Nation and its People Alan Pope October 31st, 2006 I dedicate this Report to the children of Kashechewan Alan Forward I was appointed by the Government of Canada on June 6, 2006 as Special Representative of the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in the matter of the current issues and future relocation options of the community of Kashechewan. My mandate is to consult with Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, the Government of Ontario, and the Kashechewan First Nation and to present to the Minister, the Honourable Jim Prentice, a plan that offers long-term and sustainable improvements to the lives of all Kashechewan residents. Included in this plan is a consideration of relocation site options and the recommendation of the one that will offer the greatest advantages of improved economic and individual opportunities to the members of the Kashechewan First Nation. I am also to recommend to the Minister the appropriate levels of financial and process management to implement the plan. In fulfilling this mandate I have examined and made recommendations concerning community, health, and social services and facilities in Kashechewan; financial issues affecting community life; and internal community governance issues. All of these matters will affect the quality of life in the new community, regardless of where it is located. My research consisted of a review of historical documents and information, investigation of current deficiencies in community services, interviews with band councils and individual council members, discussions in public meetings and private visits with numerous families and members of the Kashechewan First Nation, surveys of young people and community members, open houses, and advice from administrators and service providers throughout northeastern Ontario.