Hugh Buchanan Paints the John Murray Archive Austen, Byron, Conan Doyle, Etc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Kathryn Sutherland

JANE AUSTEN’S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM by kathryn sutherland Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. It works in two directions: it considers references to Austen in the papers of John Murray II, finding some previously overlooked details; and it uses the example of Austen to draw out some implications of searching amongst the diverse papers of a publishing house for evidence of a relatively unknown (at the time) author. Together, the two approaches argue for the value of archival work in providing a fuller context of analysis. After an overview of Austen’s relations with Egerton and Murray, the essay takes the form of two case studies. The first traces a chance connection in the Murray papers between Austen’s fortunes and those of her Swiss contemporary, Germaine de Stae¨l. The second re-examines Austen’s move from Egerton to Murray, and the part played in this by William Gifford, editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review and his regular reader for the press. Although Murray made his offer for Emma in autumn 1815, letters in the archive show Gifford advising him on one, possibly two, of Austen’s novels a year earlier, in 1814. Together, these studies track early testimony to authorial esteem. The essay also attempts to draw out some methodological implications of archival work, among which are the broad informational parameters we need to set for the recovery of evidence. -

'Discover' Issue 41 Pages 11-25 (PDF)

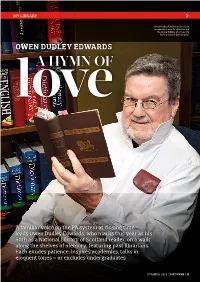

MY LIBRARY Owen Dudley Edwards’s father said he owed his career to a librarian and the former Edinburgh University history lecturer gets his point OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS love A HYMN OF A familiar voice on the PA system at closing time leads Owen Dudley Edwards, who marks this year as his 50th as a National Library of Scotland reader, on a walk along the shelves of memory, featuring past librarians. Each exudes patience, inspires academics, talks in eloquent tones – or excludes undergraduates SUMMER 2019 | DISCOVER | 11 MY LIBRARY t is 6.40pm on Monday to Thursday, of authoritative Irish historiography or else 4.40pm on Friday or established in the academic journal Irish Saturday, and a voice is telling us to Historical Studies. Father was giving a draw our work to a conclusion. In 10 striking proof of what academics should minutes’ time it will tell us to finish know to be a truism, that behind every Iall work and hand in any of the property scholarly enterprise is one or more of the National Library of Scotland which librarians without whom it would have we may be using. been written on water. The Library is my home away from Richard Ellmann, master-biographer home, my best beloved public workplace of Joyce and Wilde, and David Krause, since I retired from lecturing in history at critic and editor of Sean O’Casey and his the University of Edinburgh 14 years ago, Letters, told me of their own debts to but cherished by me for a half-century. the National Library of Ireland. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments This is a book about books— books of travel and of exploration that sought to describe, examine, and explain different parts of the world, between the late eighteenth century and the mid- nineteenth century. Our focus is on the works of non- European exploration and travel published by the house of Murray, Britain’s leading publisher of travel accounts and exploration nar- ratives in this period, between their fi rst venture in this respect, the 1773 publication of Sydney Parkinson’s A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour, and Leopold McClintock’s The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas (1859), and with the activities of John Murray I (1737– 93), John Murray II (1778– 1843), and John Murray III (1808– 92) in turning authors’ words into print. This book is also about the world of bookmaking. Publishers such as Murray helped create interest in the world’s exploration and in travel writing by offering authors a route to social standing and sci- entifi c status— even, to a degree, literary celebrity. What is also true is that the several John Murrays and their editors, in working with their authors’ often hard- won words, commonly modifi ed the original accounts of explor- ers and travelers, partly for style, partly for content, partly to guard the reputation of author and of the publishing house, and always with an eye to the market. In a period in which European travelers and explorers turned their attention to the world beyond Europe and wrote works of lasting sig- nifi cance about their endeavors, what was printed and published was, of- ten, an altered and mediated version of the events of travel and exploration themselves. -

The First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42 44

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Reading between the lines, 1839-1939 : popular narratives of the Afghan frontier Thesis How to cite: Malhotra, Shane Gail (2013). Reading between the lines, 1839-1939 : popular narratives of the Afghan frontier. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000d5b1 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Title Page Name: Shane Gail Malhotra Affiliation: English Department, Faculty of Arts, The Open University Dissertation: 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier' Degree: PhD, English Disclaimer 1: I hereby declare that the following thesis titled 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier', is all my own work and no part of it has previously been submitted for a degree or other qualification to this or any other university or institution, nor has any material previously been published. Disclaimer 2: I hereby declare that the following thesis titled 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier' is within the word limit for PhD theses as stipulated by the Research School and Arts Faculty, The Open University. -

148 Archivaria 77 As the Foregoing Examples Demonstrate, the Books

148 Archivaria 77 As the foregoing examples demonstrate, the books differ in approach, tone, and purpose, and each has different strengths. Harris aims to provide a com- prehensive, concise, and objective overview of Canadian copyright law. Murray and Trosow do not claim to be comprehensive; instead, they cover selected top- ics, often in some depth, although they fall short on the details of the law. In some cases, Harris provides more detail. Nor do Murray and Trosow claim to be objective – their stance is clearly pro-user, and they are prepared to state their opinions and speculate about the interpretation of certain provisions in new ways that make more copyright-protected material legally available for use. Rapid technological change has completely altered the copyright landscape, and applying copyright in the digital environment continues to be a challenge. Information professionals ignore copyright at their peril. For that reason, both books deserve a place on the Canadian information professional’s bookshelf. One can never have too many copyright resources readily available, and these new editions are a welcome and accessible addition to support our understand- ing of copyright. Jean Dryden Toronto The Story Behind the Book: Preserving Authors’ and Publishers’ Archives. LAURA MILLAR. Vancouver: Canadian Centre for Studies in Publishing, 2009. 224 pp. ISBN 978-0-9738727-4-3. In this smoothly written book, Laura Millar presents a concise introduction to archives, archivists, and basic records management, gearing it to the needs of authors and others in the publishing field. This work expands on Millar’s slim 1989 volume, Archival Gold: Managing & Preserving Publishers’ Records, also issued by the Canadian Centre for Studies in Publishing at Simon Fraser University. -

'Discover' Issue 29 (PDF)

THE MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF SCOTLAND | WWW.NLS.UK | ISSUE 29 SUMMER 2015 CELEBRATING PENGUIN AT 80 JARVIS COCKER P–P–P–PICKS HIS FAVOURITE PAPERBACK PLUS VAL McDERMID INVESTIGATES THE BEAUTIFUL GAME LIFTING THE LID ON THE HISTORY OF COOKING CUSTOMER MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR WELCOME Penguins on parade Now in its eighth decade, we reveal how one of the world’s most iconic publishers continues to delight readers in the digital age What do the singer Jarvis her beloved club. Read about Cocker, the former footballer her journey on page 12. Pat Nevin and the children’s We invite you to use all DISCOVER author Lauren Child have in the senses in this issue as Issue 29 summer 2015 common? Tey all treasure a we launch our exhibition, dog-eared paperback from Lifting the Lid, as part of CONTACT US We welcome all comments, questions, one of the world’s most iconic the Year of Food and Drink submissions and subscription enquiries. publishers. in Scotland. Please write to us at the National Library So many of us have a To celebrate, Sue Lawrence, of Scotland address below or email treasured Penguin book the former MasterChef [email protected] tucked away somewhere, winner, has created a cake FOR THE NATIONAL LIBRARY bought for a long train from a vintage recipe found EDITOR-IN-CHIEF journey, handed down by in our collections. You can Alexandra Miller a loved one, or picked up in read about the chef’s culinary EDITORIAL ADVISER a second-hand bookshop. adventure and find her Willis Pickard Eight decades after Penguin recipe on page 21. -

Issues) and Begin with the Summer Is• Sue

AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY A i ^/^JLiXtiLnJ** fay* ZuL ju *~x s*~ ~f"'/^/^^%& / Printers in the Kitchen and Other Recent Discoveries: G. E. Bentley, Jr.'s Annual Checklist VOLUME 39 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 2005 £%Uae AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY www.blakequarterly.org VOLUME 39 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 2005 CONTENTS Article Blake's Proverbs of Hell: St. Paul and the Nakedness of Woman William Blake and His Circle: By Howard Jacobson 48 A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2004 By G. E. Bentley, Jr. Review Minute Particulars Joyce H. Townsend, ed., William Blake: The Painter at Work Reviewed by Alexander Gourlay 49 Blake's Four ... "Zoa's"? By Justin Van Kleeck 38 Poem William Blake's A Pastoral Figure: Some Newly Revealed Verso Sketches Cold Colloquy By Robert N. Essick 44 By Warren Stevenson 54 "Great and Singular Genius": Further References to Blake (and Cromek) in the Scots Magazine By David Groves 47 ADVISORY BOARD G. E. Bentley, Jr., University of Toronto, retired Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia Martin Butlin, London Anne K. Mellor, University of California, Los Angeles Detlef W Dorrbecker, University of Trier Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Robert N. Essick, University of California, Riverside David Worrall, The Nottingham Trent University Angela Esterhammer, University of Western Ontario CONTRIBUTORS G. E. Bentley, Jr., 246 Macpherson Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4V 1A2 Canada G. E. BENTLEY, JR., writes on Blake's bibliography, biography, Nelson Hilton, Department of English, University of texts—and copperplates (in press). Georgia, Athens GA 30602 Email: [email protected] JUSTIN VAN KLEECK is a Ph.D. -

Alex Park Diss After Defense 1013

BYRON’S DON JUAN: FORMS OF PUBLICATION, MEANINGS, AND MONEY A Dissertation by JAE YOUNG PARK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2011 Major Subject: English Byron’s Don Juan: Forms of Publication, Meanings, and Money Copyright 2011 Jae Young Park BYRON’S DON JUAN: FORMS OF PUBLICATION, MEANINGS, AND MONEY A Dissertation by JAE YOUNG PARK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terence Hoagwood Committee Members, Margaret Ezell Clinton Machann James M. Rosenheim Head of Department, Nancy Warren December 2011 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Byron’s Don Juan: Forms of Publication, Meanings, and Money. (December 2011) Jae Young Park, B.A., Sungkyunkwan University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terence Hoagwood This dissertation examines Byron’s Don Juan and his attitude towards profits from the copyright money for publishing his poems. Recent studies on Don Juan and Byron have paid great attention to the poem especially in terms of the author’s status as an unprecedented noble literary celebrity. Thus the hermeneutics of the poem has very often had a tendency to bind itself within the biographical understanding of the poet’s socio-political practices. It is true that these studies are meaningful in that they highlighted and reconsidered the significance of the author’s unique life so as to illustrate biographical and historical contexts of this Romantic text. -

National Library of Scotland

About the National Library of Scotland The National Library of Scotland is a major European research library and one of the world’s leading centres for the study of Scotland and the Scots - an information treasure trove for Scotland’s knowledge, history and culture. The Library’s collections are of world-class importance. The Library holds well over 14 million items, including printed items, approximately 100,000 manuscripts and nearly 2 million maps. Every week it collects approximately 6,000 new items via Legal Deposit. Since 2008 NLS also incorporates the Scottish Screen Archive, Scotland's national moving image collection. It holds more than 32,000 films and videos presenting over 100 years of Scotland's history. Manuscripts and archives are the responsibility of the Manuscripts Division. The first manuscript was acquired by the predecessor of the NLS, the Advocates Library, in 1683, and since 1925 the Library has been the repository of the major collections of manuscripts and archives which cover many aspects of the lives, activities and interests of Scots at home and abroad. The Library is a major centre for David Livingstone studies, with a large collection of letters, journals, maps and other papers of Livingstone, and papers of several friends and associates in his African missions and explorations, including figures such as Sir Henry M. Stanley, Sir John Kirk and Robert Moffat. The collection also features diary segments written by Livingstone on his final expedition, which would later be written up in his Last Journal . Livingstone wrote the entries in 1870- 71on scraps of paper and on pages torn from printed books and newspapers. -

JANE AUSTEN's DEALINGS with JOHN MURRAY and HIS FIRM Author(S): KATHRYN SUTHERLAND Source: the Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol

JANE AUSTEN'S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM Author(s): KATHRYN SUTHERLAND Source: The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 64, No. 263 (FEBRUARY 2013), pp. 105-126 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42003759 Accessed: 20-03-2019 20:14 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42003759?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Review of English Studies This content downloaded from 158.110.4.31 on Wed, 20 Mar 2019 20:14:58 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JANE AUSTEN'S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM BY KATHRYN SUTHERLAND Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2007/May

AL Direct, May 2, 2007 Contents U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online D.C. Update Division News Round Table News Awards Seen Online May 2, 2007 Tech Talk Actions & Answers Calendar U.S. & World News New York Public Library acquires gay rights archive A major archive of papers relating to the early gay-rights movement in America has been donated to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division. The Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Gay History Papers and Photographs consist Be at conference 7:30 of letters, photographs, handbills, p.m. on June 22 for the manuscripts, publications, and ephemera world premiere of The accumulated over nearly 50 years by the late Hollywood Librarian, a activist and writer Gittings (1932–2007) and her life partner, film by writer and photojournalist and author Lahusen.... director Ann Seidl that focuses on the work and Congressional chairmen request EPA briefing lives of librarians in the Four committee chairmen in the U.S. House of Representatives have entertaining and signed a letter to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator appealing context of Stephen Johnson requesting an update on the agency’s recent American movies. activities with regard to its libraries. With a deadline of May 4, the inquiry concerns recent reports about the continued disposal or dispersal of library materials, even after recent testimony from Johnson that a moratorium on such activities had been put into place.... Providence okays 60 pink slips, just in case With negotiations continuing between Providence (R.I.) Public Library officials and city leaders about the municipal contribution for FY2008 to the operating budget of the private nonprofit library, the PPL board approved April 26 sending layoff notices to as many as 60 of the library’s nearly 100 staff members. -

Issues) and Searcher Based at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, Begin with the Summer Issue

AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY Blake Books: Publications and Discoveries, 2006 VOLUME 41 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 2007 &Uk e AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY www.blakequarterly.org VOLUME 41 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 2007 CONTENTS Article Minute Particulars William Blake and His Circle: Blake in the Times Digital Archive A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2006 By Keri Davies 45 By G. E. Bentley, Jr., with the Assistance ofHikari Sato for Japanese Publications "VISIONS OP BLAKE, THE ARTIST": An Early Reference to William Blake in the Timet By Angus Whitehead 46 Review Blake Society Annual Lecture, 28 November 2006: Patti Smith at St. James's Church, Piccadilly Reviewed by Magnus Ankarsjo ■II ADVISORY BOARD (,. I . Bentley, Jr., University of Toronto, retired Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia Martin Butlin, London Anne K. Mellor, University of California, Los Angeles Detlcf w. Ddrrbecker, University of Trier Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Robert N. Lssick, University of California, Riverside David Worrall, The Nottingham Trent University Angela Esterhammer, University of Western Ontario CONTRIBUTORS David Worrall, Faculty of Humanities, The Nottingham Trent University, Clifton Lane, Nottingham NG11 8NS UK Email: [email protected] G. E. BENTLEY, JR., is a recovering book collector but is still ad• dicted to scholarship, at the moment to Blake's heavy metal and bibliomania (a confession) and Blake's murderesses. MAGNUS ANKARSJO ([email protected]) is a lecturer at Nottingham Trent University and Loughborough Universi• ty. He is the author of William Blake and Gender (2006) and is currently completing the manuscript of Reconstructing Blake, on the substantial changes that Blake studies are now under• going in the wake of recent discoveries about Blake's life, par• ticularly his Moravian family background.