Geography, Travel and Publishing in Mid-Victorian Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Amusement the Vehicle of Instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900

1 ‘Making amusement the vehicle of instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900 PhD Thesis submitted by Lesley Jane Delaney UCL Department of English Literature and Language 2012 SIGNED DECLARATION 2 I, Lesley Jane Delaney confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ABSTRACT 3 ABSTRACT During the course of the nineteenth century children’s early reading experience was radically transformed; late eighteenth-century children were expected to cut their teeth on morally improving texts, while Victorian children learned to read more playfully through colourful picturebooks. This thesis explores the reasons for this paradigm change through a study of the key developments in children’s publishing from 1783 to 1900. Successively examining an amateur author, a commercial publisher, an innovative editor, and a brilliant illustrator with a strong interest in progressive theories of education, the thesis is alive to the multiplicity of influences on children’s reading over the century. Chapter One outlines the scope of the study. Chapter Two focuses on Ellenor Fenn’s graded dialogues, Cobwebs to catch flies (1783), initially marketed as part of a reading scheme, which remained in print for more than 120 years. Fenn’s highly original method of teaching reading through real stories, with its emphasis on simple words, large type, and high-quality pictures, laid the foundations for modern nursery books. Chapter Three examines John Harris, who issued a ground- breaking series of colour-illustrated rhyming stories and educational books in the 1810s, marketed as ‘Harris’s Cabinet of Amusement and Instruction’. -

The Smith Family…

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO. UTAH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/smithfamilybeingOOread ^5 .9* THE SMITH FAMILY BEING A POPULAR ACCOUNT OF MOST BRANCHES OF THE NAME—HOWEVER SPELT—FROM THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY DOWNWARDS, WITH NUMEROUS PEDIGREES NOW PUBLISHED FOR THE FIRST TIME COMPTON READE, M.A. MAGDALEN COLLEGE, OXFORD \ RECTOR OP KZNCHESTER AND VICAR Or BRIDGE 50LLARS. AUTHOR OP "A RECORD OP THE REDEt," " UH8RA CCELI, " CHARLES READS, D.C.L. I A MEMOIR," ETC ETC *w POPULAR EDITION LONDON ELLIOT STOCK 62 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1904 OLD 8. LEE LIBRARY 6KIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO UTAH TO GEORGE W. MARSHALL, ESQ., LL.D. ROUGE CROIX PURSUIVANT-AT-ARM3, LORD OF THE MANOR AND PATRON OP SARNESFIELD, THE ABLEST AND MOST COURTEOUS OP LIVING GENEALOGISTS WITH THE CORDIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENTS OP THE COMPILER CONTENTS CHAPTER I. MEDLEVAL SMITHS 1 II. THE HERALDS' VISITATIONS 9 III. THE ELKINGTON LINE . 46 IV. THE WEST COUNTRY SMITHS—THE SMITH- MARRIOTTS, BARTS 53 V. THE CARRINGTONS AND CARINGTONS—EARL CARRINGTON — LORD PAUNCEFOTE — SMYTHES, BARTS. —BROMLEYS, BARTS., ETC 66 96 VI. ENGLISH PEDIGREES . vii. English pedigrees—continued 123 VIII. SCOTTISH PEDIGREES 176 IX IRISH PEDIGREES 182 X. CELEBRITIES OF THE NAME 200 265 INDEX (1) TO PEDIGREES .... INDEX (2) OF PRINCIPAL NAMES AND PLACES 268 PREFACE I lay claim to be the first to produce a popular work of genealogy. By "popular" I mean one that rises superior to the limits of class or caste, and presents the lineage of the fanner or trades- man side by side with that of the nobleman or squire. -

Respicite Astra: a Historic Journey in Astronomy Through Books

0 Respicite Astra: A Historic Journey in Astronomy through Books RReessppiicciittee AAssttrraa A Historic Journey in Astronomy through Books The Astronomiicall Sociiety of Mallta The Natiionall Liibrary of Mallta The Astronomical Society of Malta The National Library of Malta 1 Respicite Astra: A Historic Journey in Astronomy through Books Respicite Astra A Historic Journey in Astronomy through Books Exhibition held between 25 September – 18 October 2010-09-21 at the National Library, Valletta, Malta on the occasion of Notte Bianca 2010 Introductory Text Mr Victor Farrugia Captions Mr Leonard Ellul Mercer – Pgs 23-24, 57 Mr Alexander Pace – Pgs 25-26, 58, 63, 70 Prof Frank Ventura – Pgs 4, 6-13, 15-18, 21, 27-31, 33, 35-38, 40, 42- 43, 45-48, 50-56, 60-62, 65-69, 72-76, 80, 85, 87, 93 Acknowledgements The Committee of the Astronomical Society of Malta would like to acknowledge the following persons for their kind and generous help in setting up this Exhibition at the Main Hall of the National Library starting on 25th September 2010 during the Notte Bianca event: Mr Fabio Agius (MaltaPost Philatelic Archives) Ms C Michelle Buhagiar (National Library of Malta) Ms Maroma Camilleri National Library of Malta) Mr Leonard Ellul Mercer (Personal capacity) Victor Farrugia (Astronomical Society of Malta) Mr Alexander Pace (Astronomical Society of Malta) Arch Alexei Pace (Astronomical Society of Malta) Ms Joanne Sciberras (National Library of Malta) Mr Tony Tanti (Astronomical Society of Malta) Prof Frank Ventura (University of Malta) Staff of the National Library of Malta Front Image Great Orion Nebula by Mr Leonard Ellul Mercer Production The Astronomical Society of Malta P.O. -

By Kathryn Sutherland

JANE AUSTEN’S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM by kathryn sutherland Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. It works in two directions: it considers references to Austen in the papers of John Murray II, finding some previously overlooked details; and it uses the example of Austen to draw out some implications of searching amongst the diverse papers of a publishing house for evidence of a relatively unknown (at the time) author. Together, the two approaches argue for the value of archival work in providing a fuller context of analysis. After an overview of Austen’s relations with Egerton and Murray, the essay takes the form of two case studies. The first traces a chance connection in the Murray papers between Austen’s fortunes and those of her Swiss contemporary, Germaine de Stae¨l. The second re-examines Austen’s move from Egerton to Murray, and the part played in this by William Gifford, editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review and his regular reader for the press. Although Murray made his offer for Emma in autumn 1815, letters in the archive show Gifford advising him on one, possibly two, of Austen’s novels a year earlier, in 1814. Together, these studies track early testimony to authorial esteem. The essay also attempts to draw out some methodological implications of archival work, among which are the broad informational parameters we need to set for the recovery of evidence. -

RECONNAISSANCE Autumn 2021 Final

Number 45 | Autumn 2021 RECONNAISSANCE The Magazine of the Military History Society of New South Wales Inc ISSN 2208-6234 BREAKER MORANT: The Case for A Pardon Battle of Isandlwana Women’s Wartime Service Reviews: Soviet Sniper, Villers-Bretonneux, Tragedy at Evian, Atom Bomb RECONNAISSANCE | AUTUMN 2021 RECONNAISSANCE Contents ISSN 2208-6234 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 Page The Magazine of the Military History Society of NSW Incorporated President’s Message 1 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 (June 2021) Notice of Next Lecture 3 PATRON: Major General the Honourable Military History Calendar 4 Justice Paul Brereton AM RFD PRESIDENT: Robert Muscat From the Editor 6 VICE PRESIDENT: Seumas Tan COVER FEATURE Breaker Morant: The Case for a Pardon 7 TREASURER: Robert Muscat By James Unkles COUNCIL MEMBERS: Danesh Bamji, RETROSPECTIVE Frances Cairns 16 The Battle of Isandlwana PUBLIC OFFICER/EDITOR: John Muscat By Steve Hart Cover image: Breaker Morant IN FOCUS Women’s Wartime Service Part 1: Military Address: PO Box 929, Rozelle NSW 2039 26 Service By Dr JK Haken Telephone: 0419 698 783 Email: [email protected] BOOK REVIEWS Yulia Zhukova’s Girl With A Sniper Rifle, review 28 Website: militaryhistorynsw.com.au by Joe Poprzeczny Peter Edgar’s Counter Attack: Villers- 31 Blog: militaryhistorysocietynsw.blogspot.com Bretonneux, review by John Muscat Facebook: fb.me/MHSNSW Tony Matthews’ Tragedy at Evian, review by 37 David Martin Twitter: https://twitter.com/MHS_NSW Tom Lewis’ Atomic Salvation, review by Mark 38 Moore. Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-532012013 © All material appearing in Reconnaissance is copyright. President’s Message Vice President, Danesh Bamji and Frances Cairns on their election as Council Members and John Dear Members, Muscat on his election as Public Officer. -

Henry Stevens Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft258003k1 No online items Finding Aid for the Henry Stevens Papers, ca. 1819-1886 Processed by Saundra Taylor and Christine Chasey; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Henry Stevens 801 1 Papers, ca. 1819-1886 Finding Aid for the Henry Stevens Papers, ca. 1819-1886 Collection number: 801 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Saundra Taylor and Christine Chasey Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging by: Apex Data Services Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, May 2003 © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Henry Stevens Papers, Date (inclusive): ca. 1819-1886 Collection number: 801 Creator: Stevens, Henry, 1819-1886 Extent: 71 boxes (35.5 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Henry Stevens (1819-1886) was a London bookseller, bibliographer, publisher, and an expert on early editions of the English Bible and early voyages and travels to America. -

The Book of Burtoniana

The Book of Burtoniana Letters & Memoirs of Sir Richard Francis Burton Volume 2: 1865-1879 Edited by Gavan Tredoux i [DRAFT] 8/26/2016 4:36 PM © 2016, Gavan Tredoux. http://burtoniana.org. The Book of Burtoniana: Volume 1: 1841-1864 Volume 2: 1865-1879 Volume 3: 1880-1924 Volume 4: Register and Bibliography Contents. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................................................................................... VIII 1865-1869. ........................................................................................................... 1 1. 1865/—/—? RICHARD BURTON TO SAMUEL SHEPHEARD....................................... 1 2. 1865/01/01? ISABEL BURTON TO MONCKTON MILNES. ........................................ 1 3. 1865/01/03. KATHERINE LOUISA (STANLEY) RUSSELL............................................ 2 4. 1865/01/07. LORD JOHN RUSSELL..................................................................... 3 5. 1865/01/08. LORD JOHN RUSSELL..................................................................... 4 6. 1865/01/09. LORD JOHN RUSSELL..................................................................... 5 7. 1865/01/09. KATHERINE LOUISA (STANLEY) RUSSELL............................................ 5 8. 1865/02/09. ISABEL BURTON TO MONCKTON MILNES. ......................................... 5 9. 1865/04/22. RICHARD BURTON TO FRANK WILSON. ............................................ 6 10. 1865/05/02? RICHARD BURTON TO JAMES HUNT. ........................................... 7 11. 1865/06/02. FREDERICK HANKEY TO MONCKTON -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex MPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the aut hor, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details THE MEANING OF ICE Scientific scrutiny and the visual record obtained from the British Polar Expeditions between 1772 and 1854 Trevor David Oliver Ware M.Phil. University of Sussex September 2013 Part One of Two. Signed Declaration I hereby declare that this Thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the Award of any other degree. Signed Trevor David Oliver Ware. CONTENTS Summary………………………………………………………….p1. Abbreviations……………………………………………………..p3 Acknowledgements…………………………………………….. ..p4 List of Illustrations……………………………………………….. p5 INTRODUCTION………………………………………….……...p27 The Voyage of Captain James Cook. R.N.1772 – 1775..…………p30 The Voyage of Captain James Cook. R.N.1776 – 1780.…………p42 CHAPTER ONE. GREAT ABILITIES, PERSEVERANCE AND INTREPIDITY…………………………………………………….p54 Section 1 William Scoresby Junior and Bernard O’Reilly. Ice and the British Whaling fleet.………………………………………………………………p60 Section 2 Naval Expeditions in search for the North West passage.1818 – 1837...........……………………………………………………………..…….p 68 2.1 John Ross R.N. Expedition of 1818 – 1819…….….…………..p72 2.2 William Edward Parry. -

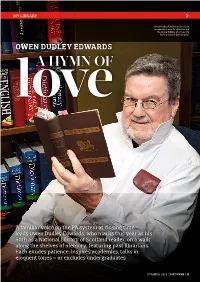

'Discover' Issue 41 Pages 11-25 (PDF)

MY LIBRARY Owen Dudley Edwards’s father said he owed his career to a librarian and the former Edinburgh University history lecturer gets his point OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS love A HYMN OF A familiar voice on the PA system at closing time leads Owen Dudley Edwards, who marks this year as his 50th as a National Library of Scotland reader, on a walk along the shelves of memory, featuring past librarians. Each exudes patience, inspires academics, talks in eloquent tones – or excludes undergraduates SUMMER 2019 | DISCOVER | 11 MY LIBRARY t is 6.40pm on Monday to Thursday, of authoritative Irish historiography or else 4.40pm on Friday or established in the academic journal Irish Saturday, and a voice is telling us to Historical Studies. Father was giving a draw our work to a conclusion. In 10 striking proof of what academics should minutes’ time it will tell us to finish know to be a truism, that behind every Iall work and hand in any of the property scholarly enterprise is one or more of the National Library of Scotland which librarians without whom it would have we may be using. been written on water. The Library is my home away from Richard Ellmann, master-biographer home, my best beloved public workplace of Joyce and Wilde, and David Krause, since I retired from lecturing in history at critic and editor of Sean O’Casey and his the University of Edinburgh 14 years ago, Letters, told me of their own debts to but cherished by me for a half-century. the National Library of Ireland. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments This is a book about books— books of travel and of exploration that sought to describe, examine, and explain different parts of the world, between the late eighteenth century and the mid- nineteenth century. Our focus is on the works of non- European exploration and travel published by the house of Murray, Britain’s leading publisher of travel accounts and exploration nar- ratives in this period, between their fi rst venture in this respect, the 1773 publication of Sydney Parkinson’s A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour, and Leopold McClintock’s The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas (1859), and with the activities of John Murray I (1737– 93), John Murray II (1778– 1843), and John Murray III (1808– 92) in turning authors’ words into print. This book is also about the world of bookmaking. Publishers such as Murray helped create interest in the world’s exploration and in travel writing by offering authors a route to social standing and sci- entifi c status— even, to a degree, literary celebrity. What is also true is that the several John Murrays and their editors, in working with their authors’ often hard- won words, commonly modifi ed the original accounts of explor- ers and travelers, partly for style, partly for content, partly to guard the reputation of author and of the publishing house, and always with an eye to the market. In a period in which European travelers and explorers turned their attention to the world beyond Europe and wrote works of lasting sig- nifi cance about their endeavors, what was printed and published was, of- ten, an altered and mediated version of the events of travel and exploration themselves. -

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005 Peter Daerden Maurits Wynants Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren Contents Foreword 7 List of abbrevations 10 P A R T O N E : H E N R Y M O R T O N S T A N L E Y 11 JOURNALS AND NOTEBOOKS 11 1. Early travels, 1867-70 11 2. The Search for Livingstone, 1871-2 12 3. The Anglo-American Expedition, 1874-7 13 3.1. Journals and Diaries 13 3.2. Surveying Notebooks 14 3.3. Copy-books 15 4. The Congo Free State, 1878-85 16 4.1. Journals 16 4.2. Letter-books 17 5. The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, 1886-90 19 5.1. Autograph journals 19 5.2. Letter book 20 5.3. Journals of Stanley’s Officers 21 6. Miscellaneous and Later Journals 22 CORRESPONDENCE 26 1. Relatives 26 1.1. Family 26 1.2. Schoolmates 27 1.3. “Claimants” 28 1 1.4. American acquaintances 29 2. Personal letters 30 2.1. Annie Ward 30 2.2. Virginia Ambella 30 2.3. Katie Roberts 30 2.4. Alice Pike 30 2.5. Dorothy Tennant 30 2.6. Relatives of Dorothy Tennant 49 2.6.1. Gertrude Tennant 49 2.6.2. Charles Coombe Tennant 50 2.6.3. Myers family 50 2.6.4. Other 52 3. Lewis Hulse Noe and William Harlow Cook 52 3.1. Lewis Hulse Noe 52 3.2. William Harlow Cook 52 4. David Livingstone and his family 53 4.1. David Livingstone 53 4.2. -

Bedfordshire People Past and Present

Bedfordshire People Past and Present 1 Bedfordshire People Past and Present This is just a selection of some of the notable people associated with Bedfordshire. Bedfordshire Borough and Central Bedfordshire libraries offer a wealth of resources, for more detailed information see the Virtual Library: www.bedford.gov.uk or www.centralbedfordshire.gov.uk Click on Libraries Click on Local and Family History Click on People The Local Studies section at Bedford Central Library also holds an archive of newspaper cuttings, biography files, an obituary index, local periodicals and books, including A Bedfordshire Bibliography by L.R. Conisbee, which has a large biography section. 2 Bedfordshire People Past Offa (? -796 BC) King Offa, regarded as one of the most powerful kings in early Anglo-Saxon England, ruled for 39 years from 757 to his death in 796. It is traditionally believed that he was buried in Bedford, somewhere near Batts Ford. Falkes De Breaute (1180-1225) A French soldier and adventurer, Falkes's loyalty to King John was rewarded with a number of titles. The king also gave him Bedford Castle, which Falkes held until 1224 when it was besieged and demolished by King Henry III. Falkes escaped and fled to the continent but died on route from food poisoning. Queen Eleanor (1244-1290) The sad death of Queen Eleanor links her to Dunstable. She died in Lincolnshire and King Edward 1st – her husband – wanted her to be buried in Westminster, thus the body was taken back to London and passed through Dunstable. The king ordered memorial crosses to be erected at every place the funeral cortege stopped overnight.