Making Amusement the Vehicle of Instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Van Ruisdael Gratis Epub, Ebook

JACOB VAN RUISDAEL GRATIS Auteur: P. Biesboer Aantal pagina's: 168 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2002-04-13 Uitgever: Waanders EAN: 9789040096044 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Dutch Painting April 8 - 14 works 95 0. January 20 - 7 works 60 0. Accept No, rather not. Add to my sets. Share it on Facebook. Share on Twitter. Pin it on Pinterest. Back to top. Similarly at this early stage of his career he absorbed some influence of contemporary landscape painters in Haarlem such as Jan van Goyen, Allart van Everdingen, Cornelis Vroom and Jacob van Mosscher. We intend to illustrate this with a selection of eight earlier works by these artists. However, there are already some remarkable differences to be found. Ruisdael developed a more dramatic effect in the rendering of the different textures of the trees, bushes and plants and the bold presentation of one large clump of oak trees leaning over with its gnarled and twisted trunks and branches highlighted against the dark cloudy sky. Strong lighting hits a sandy patch or a sandy road creating dramatic colour contrasts. These elements characterize his early works from till It is our intention to focus on the revolutionary development of Ruisdael as an artist inventing new heroic-dramatic schemes in composition, colour contrast and light effects. Our aim is to follow this deveopment with a selection of early signed and dated paintings which are key works and and show these different aspects in a a series of most splendid examples, f. Petersburg, Leipzig, München and Paris. Rubens en J. Brueghel I. Ruisdael painted once the landscape for a group portrait of De Keyser Giltaij in: Sutton et al. -

The Victorian Newsletter

The Victorian Newsletter INDEX FALL 2010 ANNOTATED INDEX 2002-2010 Compiled by Kimberly J. Reynolds Updated by Deborah Logan The Victorian Newsletter Index 2 The Victorian Newsletter Dr. Deborah A. Logan Kimberly J. Reynolds Editor Editorial Assistant Index Table of Contents Spring 2010 Page Preface 4 I. Biographical Material 5 II. Book and Film Reviews 5 III. Histories, Biographies, Autobiographies, Historical Documents 6 IV. Economics, Educational, Religious, Scientific, Social Environment 7 V. Fine Arts, Music, Photography, Architecture, City Planning, Performing Arts 10 VI. Literary History, Literary Forms, Literary Ideas 12 VII. Miscellaneous 16 VIII. Individual Authors 18 Index of Journal Authors 33 The Victorian Newsletter is sponsored for the Victorian Group of the Modern Language Association by Western Kentucky University and is published twice yearly. Editorial and business communications should be addressed to Dr. Deborah Logan, Editor, Department of English, Cherry Hall 106, Western Kentucky University, 1906 College Heights Blvd., Bowling Green, KY 42101. Manuscripts should follow MLA formatting and documentation. Manuscripts The Victorian Newsletter Index 3 cannot be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Subscription rates in the United States are $15.00 per year, and international rates, including Canada, are $17.00 USD per year. Please address checks to The Victorian Newsletter. The Victorian Newsletter Index 4 Preface In the spring of 2007, Dr. Deborah A. Logan became editor of The Victorian Newsletter after professor Ward Hellstrom‟s retirement. Since that transition, Logan preserves the tradition and integrity of the print edition whilst working tirelessly in making materials available online and modernizing the appearance and content of the academic journal. -

Fabulous Original Freddy Artwork by Wiese 152

914.764.7410 Pg 22 Aleph-Bet Books - Catalogue 90 FABULOUS ORIGINAL FREDDY ARTWORK BY WIESE 152. (BROOKS,WALTER). FREDDY THE PIG ORIGINAL ART. Offered here is RARE BROWN TITLE an original pen and ink drawing by Wiese that appears on page 19 of Wiggins for AS GOLDEN MACDONALD President (later re-issued as Freddy the Politician). The image measures 8” wide 156. [BROWN,MARGARET WISE]. BIG x 12.5” high mounted on board and is signed. The caption is on the mount and DOG LITTLE DOG by Golden Macdonald. reads” Good morning , Sir, What can we do for you?” Depicted are John Quincy Garden City: Doub. Doran (1943). 4to Adam and Jinx along with the hatted horse and they are addressing a bearded (9 1/4” square), cloth, Fine in dust wrapper man in a hat. Original Freddy work is rare. $2400.00 with some closed edge tears. 1st ed.. The story of 2 Kerry Blue terriers, written by Brown using her Golden Macdonald pseudonym. Illustrated by Leonard Weisgard and printed in the Kerry Blue color of the real dogs. One of her rarest titles. $450.00 LEONARD WEISGARD ILLUSTRATIONS 157. BROWN,MARGARET WISE. GOLDEN BUNNY. NY: Simon & Schuster (1953). Folio, glazed pictorial. boards, cover rubbed else VG. 1st ed. The title story plus 17 other stories and poems by Brown, illustrated by LEONARD WEISGARD with fabulous rich, full page color illustrations covering every page. A Big Golden Book. $200.00 158. BROWN,PAUL. HI GUY THE CINDERELLA HORSE. NY: Scribner (1944 A). 4to, cloth, Fine in sl. worn dust wrapper. -

Towards a Poetics of Becoming: Samuel Taylor Coleridge's and John Keats's Aesthetics Between Idealism and Deconstruction

Towards a Poetics of Becoming: Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s and John Keats’s Aesthetics Between Idealism and Deconstruction Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV (Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften) der Universität Regensburg eingereicht von Charles NGIEWIH TEKE Alfons-Auer-Str. 4 93053 Regensburg Februar 2004 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer EMIG Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dieter A. BERGER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE DEDICATION .............................................................................................................. I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................... II ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................... VI English........................................................................................................................ VI German...................................................................................................................... VII French...................................................................................................................... VIII INTRODUCTION Aims of the Study......................................................................................................... 1 On the Relationship Between S. T. Coleridge and J. Keats.......................................... 5 Certain Critical Terms................................................................................................ -

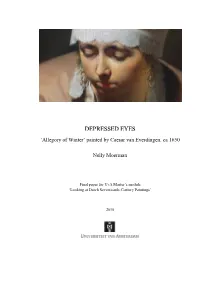

Depressed Eyes

D E P R E S S E D E Y E S ‘ Allegory of Winter’ painted by Caesar van Everdingen, c a 1 6 5 0 Nelly Moerman Final paper for UvA Master’s module ‘Looking at Dutch Seventeenth - Century Paintings’ 2010 D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 2 CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 3 2. ‘Allegory o f Winter’ by Caesar van Everdingen, c. 1650 3 3. ‘Principael’ or copy 5 4. Caesar van Everdingen (1616/17 - 1678), his life and work 7 5. Allegorical representations of winter 10 6. What is the meaning of the painting? 11 7. ‘Covering’ in a psychological se nse 12 8. Look - alike of Lady Winter 12 9. Arguments for the grief and sorrow theory 14 10. The Venus and Adonis paintings 15 11. Chronological order 16 12. Conclusion 17 13. Summary 17 Appendix I Bibliography 18 Appendix II List of illustrations 20 A ppen dix III Illustrations 22 Note: With thanks to the photographic services of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for supplying a digital reproduction. Professional translation assistance was given by Janey Tucker (Diesse, CH). ISBN/EAN: 978 - 90 - 805290 - 6 - 9 © Copyright N. Moerman 2010 Information: Nelly Moerman Doude van Troostwijkstraat 54 1391 ET Abcoude The Netherlands E - mail: [email protected] D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 3 1. Introduction When visiting the Rijksmuseum, it seems that all that tourists w ant to see is Rembrandt’s ‘ Night W atch ’. However, before arriving at the right spot, they pass a painting which makes nearly everybody stop and look. What attracts their attention is a beautiful but mysterious lady with her eyes cast down. -

COUNTRY GARDENS John Singer Sargent RA, Alfred Parsons RA, and Their Contemporaries

COUNTRY GARDENS John Singer Sargent RA, Alfred Parsons RA, and their Contemporaries Broadway Arts Festival 2012 COUNTRY GARDENS John Singer Sargent RA, Alfred Parsons RA, and their Contemporaries CLARE A. P. WILLSDON Myles Birket Foster Ring a Ring a Roses COUNTRY GARDENS John Singer Sargent RA, Alfred Parsons RA, and their Contemporaries at the premises of Haynes Fine Art Broadway Arts Festival Picton House 9th -17th June 2012 High Street Broadway Worcestershire WR12 7DT 9 - 17th June 2012 Exhibition opened by Sir Roy Strong BroadwayArtsFestival2012 BroadwayArtsFestival2012 Catalogue published by the Broadway Arts Festival Trust All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may (Registered Charity Number 1137844), be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or 10 The Green, Broadway, WR12 7AA, United Kingdom, transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the for the exhibition: prior permission of the Broadway Arts Festival Trust and Dr. Clare A.P. Willsdon ‘Country Gardens: John Singer Sargent RA, Alfred Parsons RA, and their Contemporaries’, 9th-17th June 2012 ISBN: 978-0-9572725-0-7 Academic Curator and Adviser: Clare A.P. Willsdon, British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: CONTENTS PhD (Cantab), MA (Cantab), FRHistS, FRSA, FHEA, A catalogue record for the book is available from the Reader in History of Art, University of Glasgow British Library. Country Gardens: John Singer Sargent RA, Alfred Parsons RA, and their Contemporaries ......................................................1 © Broadway Arts Festival Trust 2012 Front cover: Alfred Parsons RA, Orange Lilies, c.1911, © Text Clare A.P. Willsdon 2012 oil on canvas, 92 x 66cm, ©Royal Academy of Arts, Notes ............................................................................................................... 20 London; photographer: J. -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite . -

July 20 Catalogue.Pub

Fantasy Mystery Historical Suspense Romantica Paranormal Contemporary Bargain Basement Online ordering and email orders 24/7 Telephone ordering: 61 2 6255 7652 Email: [email protected] July 2020 Web: www.intrigueromance.com.au INTRIGUE JULY 2020 CATALOGUE HISTORICAL an will go to any lengths to win Grace back...and make her his duchess. Reconciliation is the last thing Grace desires. Unable to forgive the past, she vows ABOUT A ROGUE BK#1 $15.95 to take her revenge. But revenge requires keeping CAROLINE LINDEN Ewan close, and soon her enemy seems to be some- Desperately Seeking a Duke series. It's no love thing else altogether--something she can't resist, match... Bianca Tate is horrified when her sister even as he threatens the world she's built, the life Cathy is obliged to accept an offer of marriage from she's claimed...and the heart she swore he'd never Maximilian St. James, notorious rake. Defiantly she steal again. helps Cathy elope with her true love, and takes her sister's place at the altar. It's not even the match that A DAUNTLESS MAN $15.95 was made... Perched on the lowest branch of his LEIGH GREENWOOD family tree, Max has relied on charm and cunning to All it takes is one DAUNTLESS man… Everyone survive. But an unexpected stroke of luck gives him knows the Randolph Boys are the roughest, wildest an outside chance at a dukedom--and which Tate bunch the frontier has to offer. Madison Randolph sister he weds hardly seems to matter. But could it considers himself lucky to have escaped their dry be the perfect match? Married or not, Bianca is deter- and dusty Texas town--and the dark secrets that mined to protect her family's prosperous ceramics haunted him like a second shadow. -

RECONNAISSANCE Autumn 2021 Final

Number 45 | Autumn 2021 RECONNAISSANCE The Magazine of the Military History Society of New South Wales Inc ISSN 2208-6234 BREAKER MORANT: The Case for A Pardon Battle of Isandlwana Women’s Wartime Service Reviews: Soviet Sniper, Villers-Bretonneux, Tragedy at Evian, Atom Bomb RECONNAISSANCE | AUTUMN 2021 RECONNAISSANCE Contents ISSN 2208-6234 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 Page The Magazine of the Military History Society of NSW Incorporated President’s Message 1 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 (June 2021) Notice of Next Lecture 3 PATRON: Major General the Honourable Military History Calendar 4 Justice Paul Brereton AM RFD PRESIDENT: Robert Muscat From the Editor 6 VICE PRESIDENT: Seumas Tan COVER FEATURE Breaker Morant: The Case for a Pardon 7 TREASURER: Robert Muscat By James Unkles COUNCIL MEMBERS: Danesh Bamji, RETROSPECTIVE Frances Cairns 16 The Battle of Isandlwana PUBLIC OFFICER/EDITOR: John Muscat By Steve Hart Cover image: Breaker Morant IN FOCUS Women’s Wartime Service Part 1: Military Address: PO Box 929, Rozelle NSW 2039 26 Service By Dr JK Haken Telephone: 0419 698 783 Email: [email protected] BOOK REVIEWS Yulia Zhukova’s Girl With A Sniper Rifle, review 28 Website: militaryhistorynsw.com.au by Joe Poprzeczny Peter Edgar’s Counter Attack: Villers- 31 Blog: militaryhistorysocietynsw.blogspot.com Bretonneux, review by John Muscat Facebook: fb.me/MHSNSW Tony Matthews’ Tragedy at Evian, review by 37 David Martin Twitter: https://twitter.com/MHS_NSW Tom Lewis’ Atomic Salvation, review by Mark 38 Moore. Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-532012013 © All material appearing in Reconnaissance is copyright. President’s Message Vice President, Danesh Bamji and Frances Cairns on their election as Council Members and John Dear Members, Muscat on his election as Public Officer. -

Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 Respectable Women, Ambitious Men: Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield Autumn Mayle [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Mayle, Autumn, "Respectable Women, Ambitious Men: Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7530. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7530 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Respectable Women, Ambitious Men: Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield Autumn Mayle Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University In partial fulfillment for the requirement for the degree of Doctorate in History Katherine Aaslestad, Ph. D., Chair Joseph Hodge, Ph. D. Matthew Vester, Ph. D. Marilyn Francus, Ph. -

Toy Inventor & Designer Guide

TOY INVENTOR & DESIGNER GUIDE THIRD EDITION 2014 Imagination is the beginning of creation. You imagine what you desire, you will what you imagine and at last you create what you will. George Bernard Shaw Irish dramatist (1856-1950) Toy Inventor and Designer Guide | Second Edition Published: June 2014 | © Toy Industry Association, Inc. Comments on this Guide may be submitted to [email protected] Contents Contents 3 Getting Started 4 Coming Up with a Good Idea 5 Is it a unique and marketable idea? 5 Will it sell? 6 Is it cost-effective? 7 Is it safe? 8 Are you legally protected? 9 Entering the Marketplace 10 Selling Your Idea/Invention to a Toy Manufacturer 10 Manufacture and Distribute the Item Yourself 11 Promoting Your Idea 13 Bringing Your Product to Market 13 What Will Promotion Cost? 13 Join the Toy Industry Association Error! Bookmark not defined. Resources 15 3 Toy Inventor and Designer Guide | Third Edition (2014) © Toy Industry Association, Inc. Getting Started New ideas are the backbone of the toy industry. The need for innovative product is constant. Independent inventors and designers are an important source for new product ideas, but it can be a challenge for them to break into the industry. An original idea ― one that is fully developed to a point where it is presentable in either complete drawings or prototype format ― can be seen and it can be sold. To get started as an inventor or designer of toys or games, it’s wise to make an honest evaluation of your personal circumstances, as well as your invention. -

Copyrighted Material

1 “The Times are Unexampled”: Literature in the Age of Machinery, 1830–1850 Constructing the Man of Letters “The whole world here is doing a Tarantula Dance of Political Reform, and has no ear left for literature.” So Carlyle complained to Goethe in August of 1831 (Carlyle 1970–2006: v.327). He was not alone: the great stir surrounding prospects for electoral reform seemed for the moment to crowd aside all other literary interests. The agitation, how- ever, helped to shape a model of critical reflection that gave new weight to literature. The sense of historical rupture announced on all sides was on this view fundamentally a crisis of belief – what a later generation would call an ideological crisis. Traditional forms of faith that under- girded both the English state and personal selfhood were giving way; the times required not merely new political arrangements, but new grounds of identity and belief. Of course, that very designation reflected a skeptical castCOPYRIGHTED of mind. New myths, it seemed, MATERIAL could no longer be found in sacred texts and revelations. They would be derived from sec- ular writings and experience – something that came to be called “litera- ture” in our modern sense of the term. And the best guide to that trove of possibility would be a figure known as “the man of letters.” The most resonant versions of this story were honed through an unlikely literary exchange. In 1831 Carlyle (1795–1881), struggling to eke out a living as an author in the remote Scottish hamlet of Craigenputtoch, came upon “The Spirit of the Age,” a series of articles 99780631220824_4_001.indd780631220824_4_001.indd 2277 112/29/20082/29/2008 33:15:55:15:55 PPMM 28 Literature in the Age of Machinery, 1830–1850 in the London Examiner by John Stuart Mill (1806–73).