Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unique Opportunity for Sale Springvale Chapel 400 Springvale Road Sheffield

UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY FOR SALE SPRINGVALE CHAPEL 400 SPRINGVALE ROAD SHEFFIELD S10 1LP Former Congregational Church, 400 Springvale Road, Crookes, S10 1LP Combined size of 9,645 sq ft Description The subject property comprises the former Crookes Congregational Church, dating from 1906 and designed by the well renowned architect of the time, William John Hale. The property was converted to offices use in the early 1990’s and has been updated and refurbished over time to provide a stunning working environment, benefitting from large, open plan areas as well as excellent natural light. The refurbishment preserved many of the original features of this Grade II Listed property, including stained glass windows, original domed ceiling and mezzanine gallery area. The offices also benefit from: ▪ Fully glazed meeting room ▪ Male, female and disabled WC’s ▪ Lower ground archive/storage ▪ Fitted kitchen area ▪ Reception area ▪ Break out areas ▪ Private car park Former Congregational Church, 400 Springvale Road, Crookes, S10 1LP Combined size of 9,645 sq ft Location The property is located on Springavle Road, which links Crookes and Commonside within the popular western suburbs of Sheffield. Crookes is a well established suburban retail pitch, providing an abundance of close by local amenities. Sheffield City Centre is also within close proximity, being under 1 mile to the east. Broomhill is located 0.5miles to the south, also providing a wealth of amenities such as coffee shops, restaurants and bars. The University of Sheffield’s campus and the Teaching Hospital’s campus, including The Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield Children’s Hospital and the Charles Clifford Hospital, are situated close by. -

Making Amusement the Vehicle of Instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900

1 ‘Making amusement the vehicle of instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900 PhD Thesis submitted by Lesley Jane Delaney UCL Department of English Literature and Language 2012 SIGNED DECLARATION 2 I, Lesley Jane Delaney confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ABSTRACT 3 ABSTRACT During the course of the nineteenth century children’s early reading experience was radically transformed; late eighteenth-century children were expected to cut their teeth on morally improving texts, while Victorian children learned to read more playfully through colourful picturebooks. This thesis explores the reasons for this paradigm change through a study of the key developments in children’s publishing from 1783 to 1900. Successively examining an amateur author, a commercial publisher, an innovative editor, and a brilliant illustrator with a strong interest in progressive theories of education, the thesis is alive to the multiplicity of influences on children’s reading over the century. Chapter One outlines the scope of the study. Chapter Two focuses on Ellenor Fenn’s graded dialogues, Cobwebs to catch flies (1783), initially marketed as part of a reading scheme, which remained in print for more than 120 years. Fenn’s highly original method of teaching reading through real stories, with its emphasis on simple words, large type, and high-quality pictures, laid the foundations for modern nursery books. Chapter Three examines John Harris, who issued a ground- breaking series of colour-illustrated rhyming stories and educational books in the 1810s, marketed as ‘Harris’s Cabinet of Amusement and Instruction’. -

(25) Manor Park Sheffield He

Bus service(s) 24 25 Valid from: 18 July 2021 Areas served Places on the route Woodhouse Heeley Retail Park Stradbroke Richmond (25) Moor Market Manor Park SHU City Campus Sheffield Heeley Woodseats Meadowhead Lowedges Bradway What’s changed Service 24/25 (First) - Timetable changes. Service 25 (Stagecoach) - Timetable changes. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 24 and 25 26/05/2016# Catclie Ð Atterclie Rivelin Darnall Waverley Crookes Sheeld, Arundel Gate Treeton Ð Crosspool Park Hill Manor, Castlebeck Av/Prince of Wales Rd Ð Sheeld, Arundel Gate/ Broomhill Ð SHU City Campus Sandygate Manor, Castlebeck Av/Castlebeck Croft Sheeld, Fitzwilliam Gate/Moor Mkt Ð Manor Park, Manor Park Centre/ Ð Harborough Av 24 Nether Green Hunters Bar Sharrow Lowfield, Woodhouse, Queens Rd/ 25 Cross St/ Retail Park Tannery St Fulwood Greystones 24, 25 Nether Edge 24 25 High Storrs 25 Richmond, Heeley, Chesterfield Rd/Beeton Rd Hastilar Rd South/ 25 Richmond Rd Heeley, Chesterfield Rd/Heeley Retail Park Woodhouse, Woodhouse, Gleadless Stradbroke Rd/ Skelton Ln/ Ringinglow Sheeld Rd Skelton Grove Beighton Gleadless Valley Hackenthorpe Millhouses Norton Lees Birley Woodseats, Chesterfield Rd/Woodseats Library Herdings Charnock Owlthorpe Waterthorpe Woodseats, Chesterfield Rd/Bromwich Rd Abbeydale Beauchief High Lane Norton 24, 25 Westfield database right 2016 Dore 25 Abbeydale Park Mosborough and Greenhill Ridgeway yright p o c Halfway own 24, 25 r C Bradway, Prospect Rd/Everard Av data © 24 25 24 y e 24 v Sur e Lowedges, Lowedges Rd/The Grennel Mower c dnan Bradway, Longford Rd r O Totley Apperknowle Marsh Lane Eckington ontains C 6 = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Hail & ride Along part of the route you can stop the bus at any safe and convenient point - but please avoid parked vehicles and road junctions. -

Rotherham Sheffield

S T E A D L To Penistone AN S NE H E LA E L E F I RR F 67 N Rainborough Park N O A A C F T E L R To Barnsley and I H 61 E N G W A L A E W D Doncaster A L W N ELL E I HILL ROAD T E L S D A T E E M R N W A R Y E O 67 O G O 1 L E O A R A L D M B N U E A D N E E R O E O Y N TH L I A A C N E A Tankersley N L L W T G N A P E O F A L L A A LA E N LA AL 6 T R N H C 16 FI S 6 E R N K Swinton W KL D 1 E BER A E T King’s Wood O M O 3 D O C O A 5 A H I S 67 OA A W R Ath-Upon-Dearne Y R T T W N R S E E E RR E W M Golf Course T LANE A CA 61 D A 6 A O CR L R R B E O E D O S A N A A S A O M L B R D AN E E L GREA Tankersley Park A CH AN AN A V R B ES L S E E D D TER L LDS N S R L E R R A R Y I E R L Golf Course O N O IE O 6 F O E W O O E 61 T A A F A L A A N K R D H E S E N L G P A R HA U L L E WT F AN B HOR O I E O E Y N S Y O E A L L H A L D E D VE 6 S N H 1 I L B O H H A UE W 6 S A BR O T O E H Finkle Street OK R L C EE F T O LA AN H N F E E L I E A L E A L N H I L D E O F Westwood Y THE River Don D K A E U A6 D H B 16 X ROA ILL AR S Y MANCHES Country Park ARLE RO E TE H W MO R O L WO R A N R E RT RT R H LA N E O CO Swinton Common N W A 1 N Junction 35a D E R D R O E M O A L DR AD O 6 L N A CL AN IV A A IN AYFIELD E OOBE E A A L L H R D A D S 67 NE LANE VI L E S CT L V D T O I H A L R R A E H YW E E I O N R E Kilnhurst A W O LI B I T D L E G G LANE A H O R D F R N O 6 R A O E N I O 2 Y Harley A 9 O Hood Hill ROAD K N E D D H W O R RTH Stocksbridge L C A O O TW R N A Plantation L WE R B O N H E U Y Wentworth A H L D H L C E L W A R E G O R L N E N A -

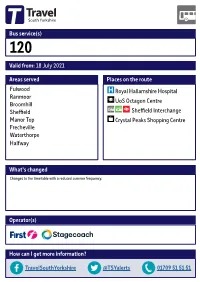

Valid From: 18 July 2021 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas Served Fulwood Ranmoor Broomhill Sheffield Manor Top Frecheville

Bus service(s) 120 Valid from: 18 July 2021 Areas served Places on the route Fulwood Royal Hallamshire Hospital Ranmoor UoS Octagon Centre Broomhill Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Manor Top Crystal Peaks Shopping Centre Frecheville Waterthorpe Halfway What’s changed Changes to the timetable with a reduced summer frequency. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 120 Walkley 17/09/2015 Sheeld, Tinsley Park Stannington Flat St Catclie Sheeld, Arundel Gate Sheeld, Interchange Darnall Waverley Treeton Broomhill,Crookes Glossop Rd/ 120 Rivelin Royal Hallamshire Hosp 120 Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/ 120 Wybourn Ranmoor Park Rd Littledale Fulwood, Barnclie Rd/ 120 Winchester Rd Western Bank, Manor Park Handsworth Glossop Road/ 120 120 Endclie UoS Octagon Centre Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/Riverdale Rd Norfolk Park Manor Fence Ô Ò Hunters Bar Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/ Fulwood Manor Top, City Rd/Eastern Av Hangingwater Rd Manor Top, City Rd/Elm Tree Nether Edge Heeley Woodhouse Arbourthorne Intake Bents Green Carter Knowle Ecclesall Gleadless Frecheville, Birley Moor Rd/ Heathfield Rd Ringinglow Waterthorpe, Gleadless Valley Birley, Birley Moor Rd/ Crystal Peaks Bus Stn Birley Moor Cl Millhouses Norton Lees Hackenthorpe 120 Birley Woodseats Herdings Whirlow Hemsworth Charnock Owlthorpe Sothall High Lane Abbeydale Beauchief Dore Moor Norton Westfield database right 2015 Dore Abbeydale Park Greenhill Mosborough and Ridgeway 120 yright p o c Halfway, Streetfields/Auckland Way own r C Totley Brook -

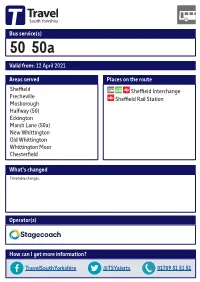

50 50A Valid From: 12 April 2021

Bus service(s) 50 50a Valid from: 12 April 2021 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Frecheville Sheffield Rail Station Mosborough Halfway (50) Eckington Marsh Lane (50a) New Whittington Old Whittington Whittington Moor Chesterfield What’s changed Timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 50 and 50a ! 05/02/2021 ! !! ! ! ! Atterclie Catclie ! Darnall! Sheeld, Interchange! ! Guilthwaite ! ! ! ! Treeton ! ! Ô ! Ô ! ! 50 50a ! 50 50a ! ! Aughton 50Ô, 50aÔ ! Handsworth ! Sharrow !! !! Manor Top, City Road/Elm Tree ! ! ! Swallownest Manor Top, City Road/Eastern Av ! Woodhouse Hurlfield ! Beighton Millhouses ! Norton Lees ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Hemsworth Charnock ! Beauchief ! Mosborough, High! Street/Cadman Street Greenhill Jordanthorpe Mosborough, High Street/Queen Street Halfway, Windmill Greenway/ Mosborough Hall Drive Lowedges 50, 50a Coal Aston Halfway, Windmill Greenway/ 50a Rotherham Road Eckington, Ravencar Road/Pasture Grove 50 50 50a Marsh Lane, Lightwood Road 50a Eckington, Pinfold Street/Bus Station Birk Hill, Fir Road Marsh Lane, Lightwood Road/Bramley Road Dronfield 50 Renishaw Unstone Hundall 50, 50a Unstone Green New Whittington, Highland Road Common Side New Whittington, High Street/The Wellington Old Whittington, High St/Bulls Head Woodthorpe Barlow Old Whittington, Burnbridge Road/Potters Close Old Whittington, Whittington Hill/Bulls Head Whittington Moor, Lidl Cutthorpe database right 2021 and yright p -

Birley Rise Road, Sheffield, S6 1HR Guide Price: £110,000

Birley Rise Road, Sheffield, S6 1HR THREE BEDROOMS | FREE HOLD | DETACHED GARAGE | SUMMER ROOM ENERGY PERFORMANCE RATING TO BE CONFIRMED Guide Price: £110,000 Birley Rise Road, Sheffield, S6 1HR FOR SALE VIA ONLINE AUCTION AUCTION * GUIDE PRICE £110,000 - £120,000 * FEES APPLY * BIDDING ENDS MONDAY 15TH JUNE 2020 AT 17:00 * FOR BIDDING AND LEGAL INFORMATION, PLEASE VISIT HUNTERS.COM/AUCTIONS * Three bedroom detached home with summer room extension and detached garage. The property briefly comprises; side entrance lobby with stairway access to the first floor, living room, dining room, rear kitchen and summer room. To the first floor is the landing, three bedrooms and bathroom. Outside there is gardens to the front and rear with stunning from to the rear ENERGY PERFORMANCE RATING «EpcGraph» The energy efficiency rating is a measure of the overall efficiency of a home. The higher the rating the more energy efficient the home is and the lower the fuel bills will be. OPENING HOURS Monday 9-5:30 Tuesday 9-5:30 Wednesday 9-5:30 Thursday 9-5:30 Friday 9-5:30 Saturday 9 - 1pm Sunday Closed THINKING OF SELLING? If you are thinking of selling your home or just curious to discover the value of your property, Hunters would be pleased to provide free, no obligation sales and marketing advice. Even if your home is outside the area covered by our local offices we can arrange a Market Appraisal through our national network of Hunters estate agents. Hunters 1 Middlewood Road, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, S6 4GU 0114 242 4260 [email protected] VAT Reg. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield Held in The

3 Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield held in the Council Chamber within the th Town Hall, Sheffield, on Wednesday, 5 May 2010 pursuant to notice duly given and Summonses duly served. PRESENT THE LORD MAYOR (Councillor Graham Oxley) THE DEPUTY LORD MAYOR (Councillor Alan Law) 1 Arbourthorne Ward 10 Dore & Totley Ward 19 Mosborough Ward Julie Dore Colin Ross David Barker John Robson Mike Davis Chris Tutt Tim Rippon Keith Hill 2 Beauchief /Greenhill Ward 11 East Ecclesfield Ward 20 Nether Edge Ward Louise McCann Colin Taylor Ali Qadar Simon Clement-Jones Vic Bowden Colin France Clive Skelton Pat White 3 Beighton Ward 12 Ecclesall Ward 21 Richmond Ward Chris Rosling-Josephs Sylvia Dunkley Lynn Rooney Helen Mirfin-Boukouris Mike Reynolds John Campbell Roger Davison Martin Lawton 4 Birley Ward 13 Firth Park Ward 22 Shiregreen & Brightside Ward Bryan Lodge Joan Barton Jane Bird Denise Fox Chris Weldon Peter Price Mike Pye Peter Rippon 5 Broomhill Ward 14 Fulwood Ward 23 Southey Ward Paul Scriven John Knight Tony Damms Shaffaq Mohammed Andrew Sangar Leigh Bramall Alan Whitehouse Janice Sidebottom Gill Furniss 6 Burngreave Ward 15 Gleadless Valley Ward 24 Stannington Ward Jackie Drayton Frank Taylor Arthur Dunworth Ibrar Hussain Denise Reaney Vickie Priestley Steve Jones Garry Weatherall David Baker 7 Central Ward 16 Graves Park Ward 25 Stocksbridge & Upper Don Ward Robert Murphy Peter Moore Jack Clarkson Jillian Creasy Ian Auckland Martin Brelsford Bernard Little Bob McCann Alison Brelsford 8 Crookes Ward 17 Hillsborough Ward 26 Walkley Ward Brian Holmes Joe Taylor Diane Leek John Hesketh Steve Ayris Penny Baker Sylvia Anginotti Janet Bragg Jonathan Harston 9 Darnall Ward 18 Manor Castle Ward 27 West Ecclesfield Ward Mary Lea Pat Midgley Kathleen Chadwick Harry Harpham Jenny Armstrong Alan Hooper Mazher Iqbal Jan Wilson Trevor Bagshaw 28 Woodhouse Ward Mick Rooney Ray Satur Council - 5th May 2010 2 1. -

Birley/Beighton/Broomhill and Sharrow Vale

State of Sheffield Sheffield of State State of Sheffield2018 —Sheffield City Partnership Board Beauchief and Greenhill/ 2018 Birley/Beighton/Broomhill and Sharrow Vale/Burngreave/ City/Crookes and Crosspool/ Darnall/Dore and Totley /East Ecclesfield/Firth Park/ Ecclesall/Fulwood/ Gleadless Valley/Graves Park/ Sheffield City Partnership Board Hillsborough/Manor Castle/ Mosborough/ Nether Edge and Sharrow/ Park and Arbourthorne/ Richmond/Shiregreen and Brightside/Southey/ Stannington/Stocksbridge and Upper Don/Walkley/ West Ecclesfield/Woodhouse State of Sheffield2018 —Sheffield City Partnership Board 03 Foreword Chapter 03 04 (#05–06) —Safety & Security (#49–64) Sheffield: Becoming an inclusive Chapter 04 Contents Contents & sustainable city —Social & Community (#07–08) Infrastructure (#65–78) Introduction (#09–12) Chapter 05 —Health & Wellbeing: Chapter 01 An economic perspective —Inclusive & (#79–90) Sustainable Economy (#13–28) Chapter 06 —Looking Forwards: Chapter 02 State of Sheffield 2018 The sustainability & —Involvement & inclusivity challenge Participation (#91–100) 2018 State of Sheffield (#29–48) 05 The Partnership Board have drawn down on both national 06 Foreword and international evidence, the engagement of those organisations and institutions who have the capacity to make a difference, and the role of both private and social enterprise. A very warm welcome to both new readers and to all those who have previously read the State of Sheffield report which From encouraging the further development of the ‘smart city’, is now entering -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

Cityview Snapshots

V May i202s0 Netwslea tter 515 North La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90036 / 323.938.2131 lic: 198603220 May 2020 Newsletter cityview.care A Message from Rosie Julinek, Executive Director CityView They always say that April showers bring May flowers, but this Snapshots year, it also brought us something absolutely unwelcome. It brought Covid-19 to all of us, alongside a quarantine life and a world-wide pandemic. But there is always hope, and it now (fingers crossed!) looks like the country has managed to flatten, if not drop the curve, entirely. The month of May also brings us the three holidays of Cinco de Mayo, Mother’s Day, and Memorial Day. Each is significant to us for different and special reasons. Cinco de Mayo, of course, is known for being a festive holiday, celebrating Mexican heritage and the significant role it plays in our own country. And since everyone has a mother, Mother’s Day is a truly meaningful holiday that has a special resonance for each of us. Whether you are celebrating the memory of your mother, or are a mother yourself, or are celebrating alongside your mother, it’s a holiday of deep emotional meaning. And finally, while Memorial Day can sometimes be a more somber holiday, it’s especially important to honor and remember those military members who have sacrificed and died Memory Care residents while serving our country. And let’s never forget that it is also a day to celebrate the life enjoying good books and we now live because of what these men and women did for us. -

Jane Taylor - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Jane Taylor - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Jane Taylor(23 September 1783 – 13 April 1824) Jane Taylor, was an English poet and novelist. She wrote the words for the song Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star in 1806 at age 23, while living in Shilling Street, Lavenham, Suffolk. The poem is now known worldwide, but its authorship is generally forgotten. It was first published under the title "The Star" in Rhymes for the Nursery, a collection of poems by Taylor and her older sister Ann (later Mrs. Gilbert). The sisters, and their authorship of various works, have often been confused, in part because their early works were published together. Ann Taylor's son, Josiah Gilbert, wrote in her biography, "two little poems–'My Mother,' and 'Twinkle, twinkle, little Star,' are perhaps, more frequently quoted than any; the first, a lyric of life, was by Ann, the second, of nature, by Jane; and they illustrate this difference between the sisters." <b>Early Life</b> Born in London, Jane Taylor and her family lived at Shilling Grange in Shilling Street Lavenham Suffolk where she wrote Twinkle Twinkle little star ,her house can still be seen, then later lived in Colchester, Essex, and Ongar. The Taylor sisters were part of an extensive literary family. Their father, Isaac Taylor of Ongar, was an engraver and later a dissenting minister. Their mother, Mrs. (Anne Martin) Taylor (1757–1830) wrote seven works of moral and religious advice, two of them fictionalized. <b>Works</b> The poem, Original Poems for Infant Minds by several young persons (i.e.