Appendix: What Happened to Jane Austen's Books?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Having Ado with Lancelot

Having Ado with Lancelot: A Chivalric Reassessment of Malory's Champion by Jesse Michael Brillinger Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (English) Acadia University Fall Convocation 2010 © Jesse Michael Brillinger 2010 This thesis by Jesse M. Brillinger was defended successfully in an oral examination on ___________. The examining committee for the thesis was: ________________________ Dr. Barb Anderson, Chair ________________________ Dr. Kathleen Cawsey, External Reader ________________________ Dr. Patricia Rigg, Internal Reader ________________________ Dr. K. S. Whetter, Supervisor _________________________ Dr. Herb Wyile, Acting Head This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (English). …………………………………………. ii I, Jesse M. Brillinger, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non‐profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. ______________________________ Jesse M. Brillinger ______________________________ K.S. Whetter, Supervisor ______________________________ Sep. 19, 2010 iii Table of Contents Introduction: Malory, Chivalry and Lancelot ............................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Medieval Chivalry in Literature and Life ............................................................ -

Play Guide Table of Contents

PLAY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 SONG LIST 3 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 MEET THE CREATORS: PAUL GORDON AND JANE AUSTEN 5 INTERVIEW WITH PAUL GORDON 7 THE NOVEL IN THE MUSIC 9 POLLOCK’S TOY THEATRES 11 LITERARY CATEGORIZATION OF AUSTEN 12 LITERARY TIMELINE 13 THE AUSTEN INDUSTRY 14 AUSTEN IN POPULAR CULTURE 15 FEMINISM IN EMMA 16 THE EMMA DEDICATION 18 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 18 HISTORICAL TIMELINE 22 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 23 Jane Austen’s Emma Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, Literary Assistant, and R Elisabeth Burton, Artistic Intern Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Associate Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation Arizona Commission on the Arts John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Bank of America Foundation National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Boeing PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City Of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William L and Ruth T Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company -

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London Christine Winter Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London Royal Holloway, University of London, 2012 2 Declaration I, Christine Winter, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 3 Abstract In the history of crime and punishment the prisons of medieval London have generally been overlooked. This may have been because none of the prison records have survived for this period, yet there is enough information in civic and royal documents, and through archaeological evidence, to allow a reassessment of London’s prisons in the later middle ages. This thesis begins with an analysis of the purpose of imprisonment, which was not merely custodial and was undoubtedly punitive in the medieval period. Having established that incarceration was employed for a variety of purposes the physicality of prison buildings and the conditions in which prisoners were kept are considered. This research suggests that the periodic complaints that London’s medieval prisons, particularly Newgate, were ‘foul’ with ‘noxious air’ were the result of external, rather than internal, factors. Using both civic and royal sources the management of prisons and the abuses inflicted by some keepers have been analysed. This has revealed that there were very few differences in the way civic and royal prisons were administered; however, there were distinct advantages to being either the keeper or a prisoner of the Fleet prison. Because incarceration was not the only penalty available in the enforcement of law and order, this thesis also considers the offences that constituted a misdemeanour and the various punishments employed by the authorities. -

JANE AUSTEN's OPEN SECRET: SAME-SEX LOVE in PRIDE and PREJUDICE, EMMA, and PERSUASION by JENNIFER ANNE LEEDS a Thesis Submitte

JANE AUSTEN’S OPEN SECRET: SAME-SEX LOVE IN PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, EMMA, AND PERSUASION By JENNIFER ANNE LEEDS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2011 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of JENNIFER ANNE LEEDS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Debbie Lee, Ph.D, Chair ___________________________________ Carol Siegel, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jon Hegglund, Ph.D. ii JANE AUSTEN’S OPEN SECRET: SAME-SEX LOVE IN PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, EMMA, AND PERSUASION Abstract by Jennifer Anne Leeds, M.A. Washington State University May 2011 Chair: Debbie Lee I argue that Austen’s famously heteronormative novels do not actually begin with compulsory heterosexuality: they arrive there gradually, contingently, and only by first carving out an authorized space in which queer relations may, or indeed must, take hold. Engaging intimacies between both men and women within Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, and Emma, I explore how Austen constructs a heteronormativity that is itself premised upon queer desire and the progressive implications this casts upon Austen as a female writer within Regency England. In each of my three chapters, I look at how same- sex intimacies are cultivated in the following social spheres: the realm of illness within Persuasion, the realm of Regency courtship within Pride and Prejudice, and the realm of domesticity within Emma. I argue that Austen conforms to patriarchal sanctions for female authorship while simultaneously undermining this sanction by depicting same-sex desire. -

By Kathryn Sutherland

JANE AUSTEN’S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM by kathryn sutherland Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. It works in two directions: it considers references to Austen in the papers of John Murray II, finding some previously overlooked details; and it uses the example of Austen to draw out some implications of searching amongst the diverse papers of a publishing house for evidence of a relatively unknown (at the time) author. Together, the two approaches argue for the value of archival work in providing a fuller context of analysis. After an overview of Austen’s relations with Egerton and Murray, the essay takes the form of two case studies. The first traces a chance connection in the Murray papers between Austen’s fortunes and those of her Swiss contemporary, Germaine de Stae¨l. The second re-examines Austen’s move from Egerton to Murray, and the part played in this by William Gifford, editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review and his regular reader for the press. Although Murray made his offer for Emma in autumn 1815, letters in the archive show Gifford advising him on one, possibly two, of Austen’s novels a year earlier, in 1814. Together, these studies track early testimony to authorial esteem. The essay also attempts to draw out some methodological implications of archival work, among which are the broad informational parameters we need to set for the recovery of evidence. -

Malory's Launcelot and Guinevere Abed Togydirs Betsy Taylor

Malory's Launcelot and Guinevere abed togydirs Betsy Taylor In Malory's account of the ambush of Launcelot in Guinevere's chamber he obliquely denies the authority of his sources: For, as the Freynshhe booke seyth, the quene and sir Launcelot were k>gydirs. And whether they were abed other at other maner of disportis, me lyste nat thereof make no mencion, for love that tyme was nat as love ys nowadayes.1 · Both his sources put Launcelot and Guinevere abed,2 but Malory says he prefers not to discuss the matter ('me lyste nat thereof make no mencion'); instead he links the lovers' activities here with the love he anatomizes, however cumbersomely, at the beginning of 'The Knight of the Cart' episode: But the olde love was nat so. For men and women coude love togydirs seven yerys, and no lycoures lustis was betwyxte them, and than was love trouthe and faythefulnes. And so in lyke wyse was used such love in kynge Arthurs dayes. (p. 1120, II. 2...{1) The benefit of Malory's reticence is twofold: he places (or attempts to place) the lovers beyond contemporary criticism, 'for love that tyme was nat as love ys nowadayes'; and he ensures that the image of Launcelot which dominates in this episode is that of the 'noble knyght' who 'toke hys swerde undir hys arme, and so he walked in hys mantell ... and put hymselff in grete jouparte' (p. 1165, 11. 5-7). In Malory's version of the episode we pass from this image to 'Madame,' seyde sir Launcelot, 'ys there here ony armour within you that myght cover my body wythall?' (p. -

A) “William Shakespeare: La Dialettica D'amore

LETTERATURA INGLESE III^ Programma a.a. 2011- 12 (prof. Michele Goffredo) A) “William Shakespeare: la dialettica d’amore ” Testi: William Shakespeare, As You Like It (qualsiasi edizione inglese o con testo a fronte) William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet (qualsiasi edizione inglese o con testo a fronte) William Shakespeare, Sonnets (qualsiasi edizione inglese o con testo a fronte) William Shakespeare, Othello (qualsiasi edizione inglese o con testo a fronte) William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra (qualsiasi edizione inglese o con testo a fronte) Testi critici: La bibliografia critica sarà indicata in seguito. I testi critici verranno, in massima parte, raccolti in una dispensa a cura del docente. B) Storia della letteratura inglese: “Dalle origini alla chiusura dei teatri del 1642” 1) Testo consigliato: Paolo Bertinetti (a cura di), Storia della letteratura inglese, Vol I° (pp.3- 206), Einaudi 2) Franco Marenco, La parola in scena, La comunicazione teatrale nell’età di Shakespeare, UTET, Torino 2004 3) Sei testi a scelta dello studente tra i seguenti. Tra i testi di uno stesso autore ne va scelto solo uno. Beowulf Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Pearl William Langland, Piers Plowman Geoffrey Chaucer, Canterbury Tales Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur Everyman Thomas More, Utopia Philip Sidney, Astrophil and Stella (1591) Philip Sidney, Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia (Old Arcadia) Philip Sidney, New Arcadia Edmund Spenser, The Fairie Queene (1590-96) Thomas Nashe, The Unfortunate Traveller, or The Life of Jack Wilton (1594) Thomas Kyd, -

The Arthurian Legend in British Women's Writing, 1775–1845

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research @ Cardiff Avalon Recovered: The Arthurian Legend in British Women’s Writing, 1775–1845 Katie Louise Garner B.A. (Cardiff); M.A. (Cardiff) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University September 2012 Declaration This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… Acknowledgements First thanks are due to my supervisors, Jane Moore and Becky Munford, for their unceasing assistance, intellectual generosity, and support throughout my doctoral studies. -

(De)Constructing Jane: Converting Austen in Film Responses Karen Gevirtz, Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University From the SelectedWorks of Karen Bloom Gevirtz Winter 2010 (De)Constructing Jane: Converting Austen in Film Responses Karen Gevirtz, Seton Hall University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/karen_gevirtz/3/ Karen B. Gevirtz PERSUASIONS ON-LINE V.31, NO.1 (Winter 2010) (De)Constructing Jane: Converting “Austen” in Film Responses KAREN B. GEVIRTZ Karen B. Gevirtz (email: [email protected]) is an Assistant Professor of English at Seton Hall University. She is the author of Life After Death: Widows and the English Novel, Defoe to Austen (University of Delaware Press, 2005) and articles on eighteenth-century women novelists. YOU SORT OF FEEL LIKE YOU OWN HER,” Keira Knightley says of Jane Austen in an interview, adding, “And I’m sure everybody feels the same way” (“Jane Austen”). Certainly if the last two decades are any indication, just about “everybody” does feel a claim or connection not just to the works but to Austen herself. Suzanne R. Pucci and James Thompson describe an explosion of Austen-related materials in an impressive array of media, from traditional print to cyberspace, during the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century (1). Phases appear within this effusion, however, particularly in film responses to her work. In the 1990s, films were occupied with the novels themselves. Gradually, however, film responses have shifted their focus so that by the end of the first decade of the new millennium, a large number of Austen films present the novels not as the result of brilliant literary endeavor, but as the inevitably limited product of a historically-bound being, Austen the woman. -

Pride and Prejudice

Curriculum Guide 2010 - 2011 Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Sunshine State Standards Language Arts Health Theatre • LA.7-12.1.7.2 • HE.7-12.C.1.2 • TH.A.1.7-12 • LA.7-12.1.7.3 • HE.7-12.C.2.2 • TH.D.1.7-12 • LA.7-12.2.1 • HE.7-12.C.2.3 • LA.7-12.3.1 • HE.7-12.C.2 Social Studies • LA.7-12.3.3 • SS.7-12.H.1.2 • LA.7-12.5 Historical Background and Lesson Plans used with permission by Actors’ Theatre of Louisville http://www.actorstheatre.org/StudyGuides 1 Table of Contents A Letter from the Director of Education p. 3 Pre-Performance - Educate Read the Plot Summary p. 4 Meet the Characters p. 4 Research the Historical Context p. 5 Love and Marriage p. 5 Time Period p. 5 Roles of Women p. 6 in Regency England p. 6 From Page to Stage p. 6 A Chronology of Pride and Prejudice p. 8 Speech - What’s the Big Deal? p. 8 Top Ten Ways to be Vulgar p. 9 Best and Worst Dressed p. 10 Dances p. 12 Performance - Excite Theater is a Team Sport (“Who Does What?”) p. 13 The Actor/Audience Relationship p. 14 Enjoying the Production p. 14 Post-Performance - Empower Talkback p. 15 Discussion p. 15 Bibliography p. 15 Lesson Plans & Sunshine State Standards p. 16 2 A Letter from the Director of Education “ All the world’s a stage,” William Shakespeare tells us ”and all the men and women merely players.” I invite you and your class to join us on the world of our stage, where we not only rehearse and perform, but research, learn, teach, compare, contrast, analyze, critique, experiment, solve problems and work as a team to expand our horizons. -

'Discover' Issue 41 Pages 11-25 (PDF)

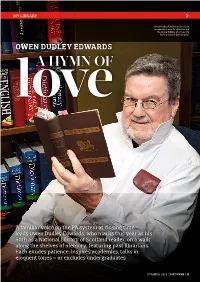

MY LIBRARY Owen Dudley Edwards’s father said he owed his career to a librarian and the former Edinburgh University history lecturer gets his point OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS love A HYMN OF A familiar voice on the PA system at closing time leads Owen Dudley Edwards, who marks this year as his 50th as a National Library of Scotland reader, on a walk along the shelves of memory, featuring past librarians. Each exudes patience, inspires academics, talks in eloquent tones – or excludes undergraduates SUMMER 2019 | DISCOVER | 11 MY LIBRARY t is 6.40pm on Monday to Thursday, of authoritative Irish historiography or else 4.40pm on Friday or established in the academic journal Irish Saturday, and a voice is telling us to Historical Studies. Father was giving a draw our work to a conclusion. In 10 striking proof of what academics should minutes’ time it will tell us to finish know to be a truism, that behind every Iall work and hand in any of the property scholarly enterprise is one or more of the National Library of Scotland which librarians without whom it would have we may be using. been written on water. The Library is my home away from Richard Ellmann, master-biographer home, my best beloved public workplace of Joyce and Wilde, and David Krause, since I retired from lecturing in history at critic and editor of Sean O’Casey and his the University of Edinburgh 14 years ago, Letters, told me of their own debts to but cherished by me for a half-century. the National Library of Ireland. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments This is a book about books— books of travel and of exploration that sought to describe, examine, and explain different parts of the world, between the late eighteenth century and the mid- nineteenth century. Our focus is on the works of non- European exploration and travel published by the house of Murray, Britain’s leading publisher of travel accounts and exploration nar- ratives in this period, between their fi rst venture in this respect, the 1773 publication of Sydney Parkinson’s A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour, and Leopold McClintock’s The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas (1859), and with the activities of John Murray I (1737– 93), John Murray II (1778– 1843), and John Murray III (1808– 92) in turning authors’ words into print. This book is also about the world of bookmaking. Publishers such as Murray helped create interest in the world’s exploration and in travel writing by offering authors a route to social standing and sci- entifi c status— even, to a degree, literary celebrity. What is also true is that the several John Murrays and their editors, in working with their authors’ often hard- won words, commonly modifi ed the original accounts of explor- ers and travelers, partly for style, partly for content, partly to guard the reputation of author and of the publishing house, and always with an eye to the market. In a period in which European travelers and explorers turned their attention to the world beyond Europe and wrote works of lasting sig- nifi cance about their endeavors, what was printed and published was, of- ten, an altered and mediated version of the events of travel and exploration themselves.