(De)Constructing Jane: Converting Austen in Film Responses Karen Gevirtz, Seton Hall University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play Guide Table of Contents

PLAY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 SONG LIST 3 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 MEET THE CREATORS: PAUL GORDON AND JANE AUSTEN 5 INTERVIEW WITH PAUL GORDON 7 THE NOVEL IN THE MUSIC 9 POLLOCK’S TOY THEATRES 11 LITERARY CATEGORIZATION OF AUSTEN 12 LITERARY TIMELINE 13 THE AUSTEN INDUSTRY 14 AUSTEN IN POPULAR CULTURE 15 FEMINISM IN EMMA 16 THE EMMA DEDICATION 18 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 18 HISTORICAL TIMELINE 22 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 23 Jane Austen’s Emma Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, Literary Assistant, and R Elisabeth Burton, Artistic Intern Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Associate Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation Arizona Commission on the Arts John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Bank of America Foundation National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Boeing PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City Of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William L and Ruth T Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

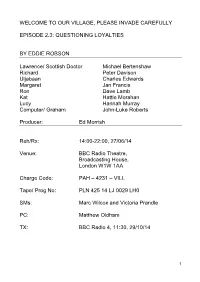

TV & Radio Script

WELCOME TO OUR VILLAGE, PLEASE INVADE CAREFULLY EPISODE 2.3: QUESTIONING LOYALTIES BY EDDIE ROBSON Lawrence/ Scottish Doctor Michael Bertenshaw Richard Peter Davison Uljabaan Charles Edwards Margaret Jan Francis Ron Dave Lamb Kat Hattie Morahan Lucy Hannah Murray Computer / Graham John-Luke Roberts Producer: Ed Morrish Reh/Rx: 14:00-22:00, 27/06/14 Venue: BBC Radio Theatre, Broadcasting House, London W1W 1AA Charge Code: PAH – 4231 – VILL Tape/ Prog No: PLN 425 14 LJ 0029 LH0 SMs: Marc Wilcox and Victoria Prandle PC: Matthew Oldham TX: BBC Radio 4, 11:30, 29/10/14 1 1 GRAMS SWARM OF EVIL (UNDER) 2 INTRO: Welcome To Our Village, Please Invade Carefully, by Eddie Robson. Episode three: Questioning Loyalties. 3 GRAMS OUT 2 SCENE 1 EXT. PARK 1 F/X: LAWRENCE, THE PARK KEEPER (40s), JANGLES HIS KEYS AS HE PREPARES TO UNLOCK A SHED. 2 KATRINA: Lawrence! Don’t open that shed! 3 LAWRENCE: Hello Katrina. How’s your mum and dad? 4 KATRINA: Normal. Just like everything else. Completely normal. 5 LAWRENCE: Must be a bit funny, living with them again, staying in your old bedroom, now you’re 34! 6 KATRINA: Yes, it’s hilarious. In fact it’s one of the most amusing things about being trapped in a village that’s been invaded by aliens and cut off from the outside world. 7 LAWRENCE: Isn’t it strange how life turns out. 8 KATRINA: It’s stranger than I expected, I’ll grant you that. 9 LAWRENCE: I need to get on and mow this grass, so if you could just let me get into the shed – 10 KATRINA: Don’t look in the shed! 11 LAWRENCE: Why not? 3 1 KATRINA: Take a break. -

JANE AUSTEN's OPEN SECRET: SAME-SEX LOVE in PRIDE and PREJUDICE, EMMA, and PERSUASION by JENNIFER ANNE LEEDS a Thesis Submitte

JANE AUSTEN’S OPEN SECRET: SAME-SEX LOVE IN PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, EMMA, AND PERSUASION By JENNIFER ANNE LEEDS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2011 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of JENNIFER ANNE LEEDS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Debbie Lee, Ph.D, Chair ___________________________________ Carol Siegel, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jon Hegglund, Ph.D. ii JANE AUSTEN’S OPEN SECRET: SAME-SEX LOVE IN PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, EMMA, AND PERSUASION Abstract by Jennifer Anne Leeds, M.A. Washington State University May 2011 Chair: Debbie Lee I argue that Austen’s famously heteronormative novels do not actually begin with compulsory heterosexuality: they arrive there gradually, contingently, and only by first carving out an authorized space in which queer relations may, or indeed must, take hold. Engaging intimacies between both men and women within Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion, and Emma, I explore how Austen constructs a heteronormativity that is itself premised upon queer desire and the progressive implications this casts upon Austen as a female writer within Regency England. In each of my three chapters, I look at how same- sex intimacies are cultivated in the following social spheres: the realm of illness within Persuasion, the realm of Regency courtship within Pride and Prejudice, and the realm of domesticity within Emma. I argue that Austen conforms to patriarchal sanctions for female authorship while simultaneously undermining this sanction by depicting same-sex desire. -

2014 Winter/Spring Season MAR 2014

2014 Winter/Spring Season MAR 2014 Bill Beckley, I’m Prancin, 2013, Cibachrome photograph, 72”x48” Published by: BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Sponsor: BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Season #ADOLLSHOUSE Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board A Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Doll’s Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer House By Henrik Ibsen English language version by Simon Stephens Young Vic Directed by Carrie Cracknell BAM Harvey Theater Feb 21 & 22, 25—28; Mar 1, 4—8, 11—15 at 7:30pm Feb 22; Mar 1, 8 & 15 at 2pm Feb 23; Mar 2, 9 & 16 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Set design by Ian MacNeil Costume design by Gabrielle Dalton Lighting design by Guy Hoare Music by Stuart Earl BAM 2014 Theater Sponsor Sound design by David McSeveney Leadership support for A Doll’s House provided by Choreography by Quinny Sacks Frederick Iseman Casting by Julia Horan CDG Associate director Sam Pritchard Leadership support for Scandinavian Hair, wigs, and make-up by Campbell Young programming provided by The Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation Literal translation by Charlotte Barslund Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Donald R. Mullen Jr. Presented in the West End by Young Vic, The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund The SHS Foundation Mark Rubinstein, Gavin Kalin, Neil Laidlaw The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

The Discrimination of Jane Austen in Miss Austen Regrets Film by Using Liberal Feminism

THE DISCRIMINATION OF JANE AUSTEN IN MISS AUSTEN REGRETS FILM BY USING LIBERAL FEMINISM Lala Nurbaiti Fadlah NIM: 204026002781 ENGLISH LETTER DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2010 THE DISCRIMINATION OF JANE AUSTEN IN MISS AUSTEN REGRETS FILM BY USING LIBERAL FEMINISM A Thesis Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Letters Scholar Lala Nurbaiti Fadlah NIM: 204026002781 ENGLISH LETTER DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2010 APPROVEMENT THE DISCRIMINATION OF JANE AUSTEN IN MISS AUSTEN REGRETS FILM BY USING LIBERAL FEMINISM A Thesis Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Letters Scholar Lala Nurbaiti Fadlah NIM. 204026002781 Approved by: Advisor Elve Oktafiyani M.Hum NIP 197810032001122002 ENGLISH LETTER DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2010 ABSTRACT Lala Nurbaiti Fadlah, the Discrimination of Jane Austen in Miss. Austen Regrets Film by Using Liberal Feminism. Skripsi. Jakarta: Adab and Humanities Faculty, UIN Syarif Hidayatullah, July 2010. The research discusses Jane Austen as the main character and tells about her life since she was a single until someone proposed her and became the writer. The research studied the discrimination of Jane Austen by using liberal feminism theory as the unit analysis. Moreover, the theory is feminism and liberal feminism at the theoretical framework of the research. The method of the research is descriptive qualitative, which tries to explain about the correlation between the discrimination Jane Austen and its influence to the literary work produced. -

The Story of China

Q2 3 Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University June 2017 THETHETHETHE STORYSTORYSTORYSTORY OFOFOFOF CHINACHINACHINACHINA 1 When to watch from A to Z listings for 3-1 are on pages 18 & 19 Channel 3-2 – June 2017 New Fly Fisher – Wednesdays, 11:00 a.m. New Mexico True TV – Sundays, 6:30 p.m. (except 4th, 11th) American Woodshop – Saturdays, 6:30 a.m.; Thursdays, 11:00 a.m. Nightly Business Report – Weekdays, 5:30 p.m. America’s Heartland – Saturdays, 6:30 p.m. (except 10th) Nova – Wednesdays, 8:00 p.m.; Saturdays, 10:00 p.m.; America’s Test Kitchen – Saturdays, 7:30 a.m.; Mondays, 11:30 a.m. Sundays, 12:00 midnight Antiques Roadshow – Mondays, 7:00 p.m. (except 5th)/8:00 p.m. “Troubled Waters” – 3rd, 4th (except 5th, 26th)/11:00 p.m.; Sundays, 7:00 a.m. “Creatures of Light” – 10th, 11th Are You Being Served? Again! – “Why Sharks Attack” – 14th, 17th, 18th Saturdays, 8:00 p.m. (except 3rd, 10th) “Making North America: Origins” – 21st (9:00 p.m.), 24th, 25th Ask This Old House – Saturdays, 4:00 p.m. (except 10th) “Making North America: Life” – 28th (9:00 p.m.), July 1st, 2nd Austin City Limits – P. Allen Smith’s Garden Home – Saturdays, 10:00 a.m. (except 3rd) Saturdays, 9:00 p.m. (except 3rd, 10th)/12:00 midnight Paint This with Jerry Yarnell – Saturdays, 11:00 a.m. Barbecue University – Thursdays, 11:30 a.m. (ends 1st) PBS NewsHour – Weekdays, 6:00 p.m./12:00 midnight BBC World News – Weekdays, 6:30 a.m./4:30 p.m.; Fridays, 5:00 p.m. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 21 August 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Wootton, S. (2018) 'Revisiting Jane Austen as a romantic author in literary biopics.', Women's writing., 25 (4). pp. 536-548. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1080/09699082.2018.1510940 Publisher's copyright statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor Francis in Women's writing on 08 Oct 2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/09699082.2018.1510940. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Peer-reviewed article accepted for publication by Taylor & Francis for Women’s Writing, 25:4, in August 2018 Sarah Wootton Abstract: This essay seeks to establish whether portrayals of Jane Austen on screen serve to reaffirm a sense of the author’s neoconservative heritage, or whether an alternative and more challenging model of female authorship is visible. -

Pride and Prejudice

Curriculum Guide 2010 - 2011 Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Sunshine State Standards Language Arts Health Theatre • LA.7-12.1.7.2 • HE.7-12.C.1.2 • TH.A.1.7-12 • LA.7-12.1.7.3 • HE.7-12.C.2.2 • TH.D.1.7-12 • LA.7-12.2.1 • HE.7-12.C.2.3 • LA.7-12.3.1 • HE.7-12.C.2 Social Studies • LA.7-12.3.3 • SS.7-12.H.1.2 • LA.7-12.5 Historical Background and Lesson Plans used with permission by Actors’ Theatre of Louisville http://www.actorstheatre.org/StudyGuides 1 Table of Contents A Letter from the Director of Education p. 3 Pre-Performance - Educate Read the Plot Summary p. 4 Meet the Characters p. 4 Research the Historical Context p. 5 Love and Marriage p. 5 Time Period p. 5 Roles of Women p. 6 in Regency England p. 6 From Page to Stage p. 6 A Chronology of Pride and Prejudice p. 8 Speech - What’s the Big Deal? p. 8 Top Ten Ways to be Vulgar p. 9 Best and Worst Dressed p. 10 Dances p. 12 Performance - Excite Theater is a Team Sport (“Who Does What?”) p. 13 The Actor/Audience Relationship p. 14 Enjoying the Production p. 14 Post-Performance - Empower Talkback p. 15 Discussion p. 15 Bibliography p. 15 Lesson Plans & Sunshine State Standards p. 16 2 A Letter from the Director of Education “ All the world’s a stage,” William Shakespeare tells us ”and all the men and women merely players.” I invite you and your class to join us on the world of our stage, where we not only rehearse and perform, but research, learn, teach, compare, contrast, analyze, critique, experiment, solve problems and work as a team to expand our horizons. -

Delbert Mann (Director), H.R

FILMOGRAPHY Dates of available productions in bold print. Sense and Sensibility 1950: Delbert Mann (director), H.R. Hays (writer), NBC, live, 60 min. 1971: David Giles (director), Denis Constanduros (writer), BBC, miniseries, 4 parts, 200 min. 1981: Rodney Bennett (director), Alexander Baron and Denis Constanduros (writers), BBC, miniseries, 7 parts, 174 min. 1995: Ang Lee (director) Emma Thompson (writer), Columbia Pictures, feature film, 136 min. 2008: John Alexander (director), Andrew Davies (writer), BBC, miniseries, 3 parts, 180 min. Modern setting versions: 1990: Sensibility and Sense, David Hugh Jones (director), Richard Nelson (writer), American Playhouse, season 9 episode 1. 2000: Kandukondain Kandukondain (I have found it). Rajiv Menon (director and writer), Sujatha (writer). Sri Surya Films, Tamil with English subtitles, 151 min. 2011: From Prada to Nada, Angel Gracia (director), Fina Torres, Luis Alfaro, Craig Fernandez (writers), OddLot Entertainment, Spanish/English, 107 min. 2011: Scents and Sensibility, Brian Brough (director), Silver Peak Productions, 89 min. (Only available in America.) Pride and Prejudice 1938: Michael Barry (director/writer), BBC, 55 min. 1940: Robert Z. Leonard (director), Aldous Huxley and Jane Murfin (writers), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, feature film, 118 min. 1949: Fred Coe (director), Samuel Taylor (writer), NBC, live, 60 min. 1952: Campbell Logan (director), Cedric Wallis (writer), BBC, live, miniseries, 6 parts, 180 min. 1958: Barbara Burnham (director), Cedric Wallis (writer, same script as 1952), BBC, live, miniseries, 6 parts, 180 min. 38 Irony and Idyll 1967: Joan Craft (director), Nemone Lethbridge (writer), BBC, miniseries, 6 parts, 180 min. 1980: Cyril Coke (director), Fay Weldon (writer), BBC, miniseries, 5 parts, 259 min. -

Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility (1811)

Programme d’agrégation 2015-2016 Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility (1811) Bibliographie sélective proposée par Isabelle Bour, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3, (roman) et par Ariane Hudelet, Université de Paris-Diderot (version filmée) 1. Roman Ouvrages bibliographiques Roth, Barry. An Annotated Bibliography of Jane Austen Studies, 1984-1994. Athens : Ohio UP, 1996. Gilson, David. A Bibliography of Jane Austen. Oxford : Clarendon, 1982. Comptes rendus de la première édition Anon. The Critical Review 4th series. 1: 2 (Feb. 1812): 149-57. Anon. The British Critic 39 (May 1812): 527. Correspondance de Jane Austen Jones, Vivien, ed. Selected Letters. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford : Oxford UP, 2009. Le Faye, Deidre, ed. Jane Austen’s Letters. 4th ed. Oxford : Oxford UP, 2014. Biographie Austen-Leigh, J.E. A Memoir of Jane Austen and other Family Recollections. 1871. Ed. Kathryn Sutherland. Oxford : Oxford UP, 2002. Fergus, Jan. Jane Austen : A Literary Life. London : Macmillan, 1991. Kaplan, Deborah. Jane Austen among Women. Baltimore : Johns Hopkins UP, 1992. Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen : A Family Record. 1989. 2nd ed. Cambridge : Cambridge UP, 2004. Tomalin, Claire. Jane Austen : A Life. Harmondsworth : Viking, 1997. Editions de Sense and Sensibility Ed. R.W. Chapman. Oxford : Oxford UP, 1923. Ed. Tony Tanner. Harmondsworth : Penguin, 1969. 1 Ed. and intr. Ros Ballaster (with the 1969 introduction by Tony Tanner). London : Penguin Classics, 1995. Ed. James Kinsley, intr. and notes Margaret Anne Doody and Claire Lamont. Oxford World’s Classics.Oxford : Oxford UP, 2008. (Edition au programme) Ed. Edward Copeland. Cambridge : Cambridge UP, 2009. Ed. Patricia Meyer Spacks. Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap P, 2013.