Proceedings of the 9Th Northumbria International Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loughborough University International Foundation Programmes

http://www.lborochina.org/ Loughborough University International Foundation Programmes A Leading University | A Successful College | One Single Campus 2 http://www.lborochina.org/ www.lboro.ac.uk Business or Science/Engineering An introduction Contents Loughborough University and Loughborough College Introduction/02 are delighted to announce the development of Entry Requirements/03 two new International Foundation Programmes in Business and Science/Engineering. Start Dates/04 Loughborough University and Loughborough College are located on a large, safe, Programme Structure/04 single site campus close to the town centre. Loughborough has a population of approximately, 57,000 with a large student population. The town and campus are Assessment/04 surrounded by beautiful, green countryside. Located in the Midlands with excellent transport links to all major cities in the UK. East Midlands Airport is just Progression/05 30 minutes away offering low cost flights to most major European capital cities. Loughborough University has won the Best Student Experience for the third year Teaching and Support/06 running in the Times 2008 awards and were winners of the Outstanding Support for Overseas Students in 2007. Her Majesty, The Queen, presented Loughborough Accommodation/07 with its sixth Queen’s Anniversary Prize for Higher and Further Education, an achievement matched only by the University of Oxford. Tuition Fees/08 During the last seven years, Loughborough has always been rated among the top Application Form/09 fifteen UK universities. In the 2008 National Student Survey the university was ranked fourth in the UK, with 91% of its students rating their overall satisfaction Local Area and Map/11 with their university. -

By Kathryn Sutherland

JANE AUSTEN’S DEALINGS WITH JOHN MURRAY AND HIS FIRM by kathryn sutherland Jane Austen had dealings with several publishers, eventually issuing her novels through two: Thomas Egerton and John Murray. For both, Austen may have been their first female novelist. This essay examines Austen-related materials in the John Murray Archive in the National Library of Scotland. It works in two directions: it considers references to Austen in the papers of John Murray II, finding some previously overlooked details; and it uses the example of Austen to draw out some implications of searching amongst the diverse papers of a publishing house for evidence of a relatively unknown (at the time) author. Together, the two approaches argue for the value of archival work in providing a fuller context of analysis. After an overview of Austen’s relations with Egerton and Murray, the essay takes the form of two case studies. The first traces a chance connection in the Murray papers between Austen’s fortunes and those of her Swiss contemporary, Germaine de Stae¨l. The second re-examines Austen’s move from Egerton to Murray, and the part played in this by William Gifford, editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review and his regular reader for the press. Although Murray made his offer for Emma in autumn 1815, letters in the archive show Gifford advising him on one, possibly two, of Austen’s novels a year earlier, in 1814. Together, these studies track early testimony to authorial esteem. The essay also attempts to draw out some methodological implications of archival work, among which are the broad informational parameters we need to set for the recovery of evidence. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

The University Library, 1 August 2005 - 31 July 2006: Report of the Librarian

LOUGHBOROUGH UNIVERSITY DIVISION OF INFORMATION SERVICES AND SYSTEMS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY The University Library, 1 August 2005 - 31 July 2006: report of the Librarian In a year in which current and former staff celebrated the Pilkington Library’s 25th anniversary at a well-attended party organised by the Admin Team, other highlights were service developments undreamed of in 1980. At the start of the academic year Library users colonised with enthusiasm the new 150-seat group learning area Open3; as it ended the Loughborough Institutional Repository moved from successful project to University-wide service, with a remarkable 1800 research papers deposited during its pilot phase. And during the year, wireless networking was installed throughout the Library. Planning To guide service development until 2010, the Library undertook one of its periodic major planning exercises. Cross-Library groups investigated areas identified at open meetings as key to medium-term planning, making many recommendations for service development. The groups’ agenda were set, and their recommendations finalised, at further open meetings. The convenors – Gary Brewerton, Elizabeth Gadd, Peter Lund and Stephanie McKeating - were congratulated on the work of their groups and the quality of their reports. Of the recommendations, some were implemented immediately; some will be included in future operational plans; and others shaped the new strategic plan,1 refined through discussion at yet more open meetings. The Library operational plan, 2005-2006 was formulated by the Management Group, and kept under review throughout the year. Operational plans produced by all Library teams and groups were similarly monitored through team meetings; half-year progress was reported to Management Group; and annual reports were written. -

Annual Congregation for The

THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ANNUAL CONGREGATION FOR THE CONFERRING OF DEGREES WEDNESDAY, MAY TWENTY-NINTH NINETEEN HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FOUR BOARD OF GOVERNORS Ex-Officio: The Chancellor The President Elected by Senate: Charles J. Connaghan, B.A., M.A. Mrs. Frederick Field, B.A. Benjamin B. Trevino, LL.B. Appointed by the Lieutenant-Governor in Council: Richard M. Bibbs, B.A.Sc. The Honourable Thomas A. Dohm, Q.C. Clive B. Lytle, B.A. Mrs. John MacD. Lecky, B.A. Allan M. McGavin, C.D., LL.D., Chairman of the Board Paul S. Plant, B.A. 1 SENATE The Chancellor: Nathaniel T. Nemetz, B.A., LL.D. The President, Chairman: Walter Henry Gage, C.C., B.A., M.A., LL.D. The Registrar, Secretary: 3. B. A. Parnall, B.A., B.Ed., M.A. THE DEANS Dean of Agricultural Sciences: Michael Shaw, B.Sc., M.Sc., Ph.D., F.LS., F.R.S.C. Dean of Applied Science: W. D. barn Finn, B.E., M.Sc., Ph.D., M.AmSoc.C.E., M.A.S.EB. Dean of Arts: D. T. Kenny, B.A., MA., Ph.D. Acting Dean of Commerce and Business Administration, C. C. Gourlay, B.Com., M.Com. Dean of Dentistry: S. Wah Leung, D.D.S., B.Sc., Ph.D. Dean of Education: J. H. M. Andrews, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. Dean of Forestry: Joseph A. F. Gardner, B.A., M.A., Ph.D., F.C.I.C. Dean of Graduate Studies: Ian McTaggart-Cowan, O.C., B.A., Ph.D., LL.D., F.R.S.C. -

Alumni ANNIVERSARIES Reunion Weekend Aerial View Campus 1986

alumni ANNIVERSARIES reunion weekend Aerial view campus 1986 Martini Girls 1984 Computer Centre instudents lab 1973 University Challenge, 1974 CONNECT WITH OLD FRIENDS HOW TO BOOK SATURDAY 12 SEPTEMBER Why not check out your class lists by visiting the Reunion Weekend website, and Registration is on a first-come-first-served basis and we anticipate the event will we can help put you back in touch with former class, Hall and sport mates. be well attended. 09.00 Information desk opens 15.15 TOURS: Design / Engineering / Free time Payment by card: Visit the Reunion Weekend webpage to access the Online Store VENUE 10.00 Vice-Chancellor’s and Alumni President’s Welcome 16.15 Refreshments break This event will be taking place at the University’s four star hotel, Burleigh Court. Payment by cheque: Complete the enclosed booking form and return in the This £8 million complex, situated in the West Park on campus, has recently been pre-paid envelope provided along with your cheque. 11.00 Refreshments break 16.45 Free time awarded Gold in the Hotel of the Year category at the Leicester and Leicestershire Once we have received your booking we will confirm your place, by email or post, Excellence in Tourism Awards. within one week. Booking closes on Monday 24 August 2015. 11.30 TALKS: Loughborough Sport / A Day in the Life of a 18.30 Drinks reception Student: Then and Now /Engineering Talk DRESS CODE Cancellation Policy: Please note we are unable to offer any refunds after 19.30 Gala dinner and disco For most of the weekend, we suggest you wear casual clothing, bring an umbrella 24 August. -

Spatial Dev Plan Southern Dist Technical

Technical draft 1: SDP / EMF Southern District (H) - for comment and discussion only August 2009 1 Technical draft 1: SDP / EMF Southern District (H) - for comment and discussion only August 2009 2 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 LEGAL STATUS AND VALIDITY .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.3 KEY COMPONENTS OF THE DISTRICT SDP AND EMF ............................................................................................ 2 1.4 PROCESS ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.5 STUDY AREA ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. DIRECTIVES ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL PLANNING INFORMANTS ............................................................................................ 5 2.2 METROPOLITAN AND DISTRICT PLANNING INFORMANTS ..................................................................................... -

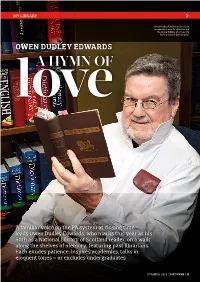

'Discover' Issue 41 Pages 11-25 (PDF)

MY LIBRARY Owen Dudley Edwards’s father said he owed his career to a librarian and the former Edinburgh University history lecturer gets his point OWEN DUDLEY EDWARDS love A HYMN OF A familiar voice on the PA system at closing time leads Owen Dudley Edwards, who marks this year as his 50th as a National Library of Scotland reader, on a walk along the shelves of memory, featuring past librarians. Each exudes patience, inspires academics, talks in eloquent tones – or excludes undergraduates SUMMER 2019 | DISCOVER | 11 MY LIBRARY t is 6.40pm on Monday to Thursday, of authoritative Irish historiography or else 4.40pm on Friday or established in the academic journal Irish Saturday, and a voice is telling us to Historical Studies. Father was giving a draw our work to a conclusion. In 10 striking proof of what academics should minutes’ time it will tell us to finish know to be a truism, that behind every Iall work and hand in any of the property scholarly enterprise is one or more of the National Library of Scotland which librarians without whom it would have we may be using. been written on water. The Library is my home away from Richard Ellmann, master-biographer home, my best beloved public workplace of Joyce and Wilde, and David Krause, since I retired from lecturing in history at critic and editor of Sean O’Casey and his the University of Edinburgh 14 years ago, Letters, told me of their own debts to but cherished by me for a half-century. the National Library of Ireland. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments This is a book about books— books of travel and of exploration that sought to describe, examine, and explain different parts of the world, between the late eighteenth century and the mid- nineteenth century. Our focus is on the works of non- European exploration and travel published by the house of Murray, Britain’s leading publisher of travel accounts and exploration nar- ratives in this period, between their fi rst venture in this respect, the 1773 publication of Sydney Parkinson’s A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas, in His Majesty’s Ship, the Endeavour, and Leopold McClintock’s The Voyage of the ‘Fox’ in the Arctic Seas (1859), and with the activities of John Murray I (1737– 93), John Murray II (1778– 1843), and John Murray III (1808– 92) in turning authors’ words into print. This book is also about the world of bookmaking. Publishers such as Murray helped create interest in the world’s exploration and in travel writing by offering authors a route to social standing and sci- entifi c status— even, to a degree, literary celebrity. What is also true is that the several John Murrays and their editors, in working with their authors’ often hard- won words, commonly modifi ed the original accounts of explor- ers and travelers, partly for style, partly for content, partly to guard the reputation of author and of the publishing house, and always with an eye to the market. In a period in which European travelers and explorers turned their attention to the world beyond Europe and wrote works of lasting sig- nifi cance about their endeavors, what was printed and published was, of- ten, an altered and mediated version of the events of travel and exploration themselves. -

UNWELCOME GUESTS Iran’S Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS UNWELCOME GUESTS Iran’s Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights WATCH Unwelcome Guests Iran’s Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0770 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0770 Unwelcome Guests Iran’s Violation of Afghan Refugee and Migrant Rights Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary/Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... -

MARC Codes for Organizations in the UK and Its Dependencies

MARC codes for organizations in the UK and its dependencies Last updated: 02 September 2019 Current MARC codes for organizations This table lists current MARC codes for organizations in the UK and its dependencies. It is arranged in alphabetical order by organization name. Active MARC Codes MARC code Normalised form Name Variant or Address Town/City Postcode previous name(s) UkLHu uklhu A. J. Hurley, Ltd. Hurley, Ltd. 119-121 Charlemont London SW17 Rd. UK-AbCCL ukabccl Aberdeen City Council Library Aberdeen City Central Library, Aberdeen AB25 1GW and Information Service Libraries; Rosemount Viaduct Aberdeen Library & Information Services StAbUL stabul Aberdeen University, Library University of Bedford Road Aberdeen AB24 3AA Aberdeen StOlALI stolali Aberdeenshire Libraries Aberdeenshire Meldrum Meg Way Oldmeldrum AB51 0GN Library and Information Service; ALIS WlAbUW wlabuw Aberystwyth University Prifysgol Hugh Owen Library, Aberystwyth SY23 3DZ Aberystwyth, AU; Penglais Campus University of Wales, Aberystwyth; Prifysgol Cymru, Aberystwyth UK-LoALL ukloall Academic Library Limited 20 Cambridge Dr. London SE12 8AJ UkAc ukac Accrington Public Library Accrington UkMbAM-D ukmbamd Adam Matthew Digital Ltd Pelham House, London Malborough SN8 2AA Road UkMbAM ukmbam Adam Matthew Publications Pelham House, London Malborough SN8 2AA Ltd Road StEdAL stedal Advocates Library Parliament House Edinburgh EH1 1RF UkLoJL uklojl Aga Khan Library IIS-ISMC Joint 10 Handyside Street London N1C 4DN Library; Library of the Institute of Ismaili Studies and the Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations (Aga Khan University) StEdALDL stedaldl Agency for the Legal Deposit ALDL 33, Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SL Libraries UkLiAHC ukliahc Alder Hey Children’s NHS FT Education Centre, Liverpool L12 2AP Eaton Road UkLAC uklac American College in London, 110 Marylebone High London W1M 3DB Library St. -

The First Anglo-Afghan War, 1839-42 44

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Reading between the lines, 1839-1939 : popular narratives of the Afghan frontier Thesis How to cite: Malhotra, Shane Gail (2013). Reading between the lines, 1839-1939 : popular narratives of the Afghan frontier. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000d5b1 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Title Page Name: Shane Gail Malhotra Affiliation: English Department, Faculty of Arts, The Open University Dissertation: 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier' Degree: PhD, English Disclaimer 1: I hereby declare that the following thesis titled 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier', is all my own work and no part of it has previously been submitted for a degree or other qualification to this or any other university or institution, nor has any material previously been published. Disclaimer 2: I hereby declare that the following thesis titled 'Reading Between the Lines, 1839-1939: Popular Narratives of the Afghan Frontier' is within the word limit for PhD theses as stipulated by the Research School and Arts Faculty, The Open University.