Forest Community Integration and Collective Agency in Korup National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

MINMAP South-West Region

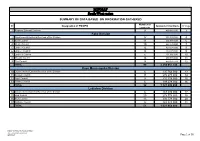

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

Mundemba Communal Development Plan

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN --------- ------------ Peace – Work – Fatherland Paix – Travail – Patrie ---------- ----------- MINISTRY OF ECONOMY, PLANNING AND MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DE LA PLANIFICATION REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT ET DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE ---------- ------------- GENERAL SECRETARY SECRETARIAT GENERAL ---------- ------------ NATIONAL COMMUNITY DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME NATIONAL DE DEVELOPPEMENT PROGRAM PARTICIPATIF ---------- ------------ SOUTHWEST REGIONAL COORDINATION UNIT CELLULE REGIONALE DE COORDINATION DE SUD ------------ OUEST ------------ MUNDEMBA COMMUNAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN June 2011 i Table of Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF ABBREVIATION ................................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................................................. viii LIST OF FIGURE .................................................................................................................................................... ix LIST OF MAPS ........................................................................................................................................................ ix LIST OF ANNEXES ............................................................................................................................................... -

SSA Infographic

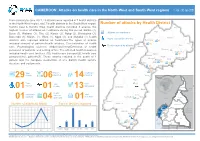

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

Programming of Public Contracts Awards and Execution for the 2020

PROGRAMMING OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS AWARDS AND EXECUTION FOR THE 2020 FINANCIAL YEAR CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING LOGBOOK OF DEVOLVED SERVICES AND OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES SOUTH-WEST REGION 2021 FINANCIAL YEAR SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 6 219 193 000 3 2 Kumba City Council 1 100 000 000 4 Fako Division 3 Divisional External Services 6 261 261 000 5 4 Buea Council 10 215 928 000 5 5 Idenau Council 10 360 000 000 6 6 Limbe I Council 12 329 000 000 7 7 Limbe II Council 9 225 499 192 8 8 Limbe III Council 13 300 180 000 9 9 Muyuka Council 10 303 131 384 10 10 Tiko Council 8 297 100 000 11 TOTAL 78 2 292 099 576 Kupe Manenguba Division 11 Divisional External Services 2 47 500 000 12 12 Bangem Council 9 267 710 000 12 13 Nguti Council 8 224 000 000 13 14 Tombel Council 10 328 050 000 13 TOTAL 29 867 260 000 Lebialem Division 15 Divisional External Services 1 32 000 000 15 16 Alou Council 13 253 000 000 15 17 Menji Council 4 235 000 000 16 18 Wabane Council 10 331 710 000 17 TOTAL 28 851 710 000 Manyu Division 19 Divisional External Services 1 22 000 000 18 20 Akwaya Council 7 339 760 000 18 21 Eyumojock Council 8 228 000 000 18 22 Mamfe Council 10 230 000 000 19 23 Tinto Council 9 301 760 000 20 TOTAL 35 1 121 520 000 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 30 SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Meme Division 24 -

Dekadal Climate Alerts and Probable Impacts for the Period 21St to 30Th October 2020

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ----------- ----------- OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR NATIONAL OBSERVATORY LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES ON CLIMATE CHANGE ----------------- ----------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECTORATE GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- ONACC www.onacc.cm; [email protected]; Tel : (+237) 693 370 504 / 654 392 529 BULLETIN N° 60 Dekadal climate alerts and probable impacts for the period 21st to 30th October 2020 st 21 October 2020 © NOCC October 2020, all rights reserved Supervision Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). Production Team (NOCC) Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, PhD student and Technical staff, NOCC. ZOUH TEM Isabella, M.Sc. in GIS-Environment and Technical staff, NOCC. NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. MEYONG René Ramsès, M.Sc. in Physical Geography (Climatology/Biogeography). ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, NOCC. ELONG Julien Aymar, M.Sc. in Business and Environmental law. I. Introduction This dekadal -

Gender in the Arts Le Genre Dans Les Arts

DOCUMENTATION AND INFORMATION CENTRE CENTRE DE DOCUMENTATION ET D’INFORMATION Gender in the Arts Le genre dans les arts Bibliography - Bibliographie CODICE June/Juin, 2006 Gender in the Arts – Le genre dans les arts Introduction Introduction The topic of the 2006 session of the Gender La session 2006 de l’institut du genre porte sur Institute is “Gender in the arts”. The arts have « le Genre dans les arts ». been defined according to the Larousse dictionary Les arts, définis d’après le Larousse comme étant as being “All specific human activities, based on « l’ensemble des activités humaines spécifiques, sensory, aesthetic and intellectual faculties”. In faisant appel à certaines facultés sensorielles, other words, arts relate to: music, painting, esthétiques et intellectuelles ». En d’autres theatre, dance, cinematography, literature, termes, les arts se confondent à tout ce qui se orature, fashion, advertisement etc. rapporte à : la musique, la peinture, le théâtre, la danse, le cinéma, la littérature, l’oralité, la mode, This bibliography produced by the CODESRIA la publicité etc. Documentation and Information Centre (CODICE) within the framework of this institute lists Cette bibliographie produite par le Centre de documents covering all the concepts on arts. It is documentation et d’information du CODESRIA divided into four parts: (CODICE) dans le cadre de cet institut recense - References compiled from CODICE Bibliographic des documents en prenant en considération tous data base; les concepts liés aux arts. Elle est divisée en - New documents ordered for this institute; quatre parties : - Specialized journals on the topic of gender and - Les références tirées de la base de arts; données du CODICE. -

In Southwest and Littoral Regions of Cameroon

UNIVERSITY OF BUEA FACULTY OF SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES MARKETS AND MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS FOR ERU (Gnetum spp.) IN SOUTH WEST AND LITTORAL REGIONS OF CAMEROON BY Ndumbe Njie Louis BSc. (Hons) Environmental Science A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Science of the University of Buea in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Natural Resources and Environmental Management July 2010 ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Almighty God who gave me the ability to carryout this project. To my late father Njie Mojemba Maximillian I and my beloved little son Njie Mojemba Maximillian II. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people: Dr A. F. Nkwatoh, of the University of Buea, for his supervision and guidance; Verina Ingram, of CIFOR, for her immense technical guidance, supervision and support; Abdon Awono, of CIFOR, for guidance and comments; Jolien Schure, of CIFOR, for her comments and field collaboration. I also wish to thank the following organisations: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the Commission des Forets d‟Afrique Centrale (COMIFAC) for the opportunity to work within their framework and for the team spirit and support. I am also very grateful to the following collaborators: Ewane Marcus of University of Buea; Ghislaine Bongers of Wageningen University, The Netherlands and Georges Nlend of University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland for their collaboration in the field. Thanks also to Agbor Demian of Mamfe.