In Southwest and Littoral Regions of Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infrastructure Causes of Road Accidents on the Yaounde – Douala Highway, Cameroon

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com International Journal of Development Research ISSN: 2230-9926 Vol. 10, Issue, 06, pp. 36260-36266, June, 2020 https://doi.org/10.37118/ijdr.18747.06.2020 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS INFRASTRUCTURE CAUSES OF ROAD ACCIDENTS ON THE YAOUNDE – DOUALA HIGHWAY, CAMEROON 1WOUNBA Jean François, 2NKENG George ELAMBO and *3MADOM DE TAMO Morrelle 1Department of Town Planning, National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon; 2Director of the National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon: 3Department of Civil Engineering, National Advanced School of Public Works Yaounde, Ministry of Public Works, P.O. Box 510, Yaounde, Cameroon ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT ArticleArticle History: History: The overall goal of this study was to determine the causes of road crashes related to road th ReceivedReceived 24xxxxxx, March, 2019 2020 infrastructure parameters on the National Road No. 3 (N3) and provide measures to improve the ReceivedReceived inin revisedrevised formform safety of all road users. To achieve this, 225 accident reports for the years 2017 and 2018 were th 19xxxxxxxx, April, 2020 2019 th collected from the State Defense Secretariat. This accident data was analyzed using the crash AcceptedAccepted 20xxxxxxxxx May, 2020, 20 19 frequency and the injury severity density criteria to obtain the accident-prone locations (7 critical Published online 25th June, 2020 Published online xxxxx, 2019 sections and 2 critical intersections) and a map presenting these locations produced with ArcGis Key Words: 10.4.1. A site visit of these locations was then performed to obtain the road infrastructure and environment data necessary to get which parameters are responsible for road crashes. -

Non-Timber Forest Products and Climate Change Adaptation Among Forest-Dependent Communities in Bamboko Forest Reserve, the Southwest Region of Cameroon

Non-timber forest products and climate change adaptation among forest-dependent communities in Bamboko forest reserve, the southwest region of Cameroon Tieminie Robinson Nghogekeh ( [email protected] ) TTRECED Cameroon Chia Eugene Loh GIZ Yaounde,Cameroon Tieguhong Julius Chupezi African Development Bank Nghobuoche Frankline Mayiadieh Universite de Yaounde I Piabuo Serge Mandiefe ICRAF-Cameroon Mamboh Rolland Tieguhong Universite de Yaounde II Research Keywords: NTFPs, Climate change, adaptation, BFR, South West Region, Cameroon Posted Date: November 19th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-61744/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on March 9th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-020-00215-z. Page 1/24 Abstract Background: Forests are naturally endowed to combat climate change by protecting people and livelihoods as well as creating a base for sustainable economic and social development. But this natural mechanism is often hampered by anthropogenic activities. It is therefore imperative to take measures that are environmentally sustainable not only for mitigation but also for its adaptation. This study was carried out to assess the role of Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) as a strategy to cope with the impacts of climate change among forest-dependent communities around the Bamkoko Forest Reserve in the South West Region of Cameroon. Methods: Datasets were collected through household questionnaires (20% of the population in each village that constitute the study site was a sample), participatory rural appraisal techniques, transect walks in the 4 corners of the Bamboko Forest Reserve with a square sample of 25 m2 x 25 m2 to identied and record NTFPs in the reserve, and direct eld observations. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights • From 25-27 April, Marie-Pierre Poirier, UNICEF Regional Director April 2018 for West and Central Africa Region visited projects in the Far North and East regions to evaluate the humanitarian situation 1,810,000 # of children in need of humanitarian and advocated for the priorities for children, including birth assistance registrations. 3,260,000 • UNHCR and UNICEF with support of WFP donated 30 tons of non- # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2018) food items including soaps to be distributed in Mamfe and Kumba sub-divisions in South West region for estimated 23,000 people Displacement affected by the Anglophone crisis. 241,000 • As part of the development of an exit strategy for Temporary #of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) Learning and Protective Spaces (TLPSs), a joint mission was 69,700 conducted to verify the situation of 87 TLPSs at six refugee sites # of Returnees and host community schools in East and Adamaoua regions. The (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) 93,100 challenge identified is how to accommodate 11,314 children who # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas are currently enrolled in the TLPSs into only 11 host community (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) 238,700 schools, with additional 7,325 children (both IDPs and host # of CAR Refugees in East, Adamaoua and community) expected to reach the school age in 2018. North regions in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) UNICEF’s Response with Partners UNICEF Appeal 2018 Sector UNICEF US$ 25.4 million Sector Total UNICEF Total Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH : People provided with 528,000 8,907 75,000 8,907 US$ 2.1 m access to appropriate sanitation Funds Education: School-aged children 4- received 17, including adolescents, accessing 411,000 11,314 280,000 11,314 US$ 1.8 m education in a safe and protective learning environment. -

Rapid Protection Assessments Summary Report

Rapid Protection Assessments Summary Report Danish Refugee Council Southwest Cameroon December 2020 Cameroon – RPA Report – December 2020 Table of Content 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Information on Key Informants (KIs) ............................................................................................ 5 2. Communities’ General Profile ..................................................................................... 6 2.1 Pre and post crisis population movements ................................................................................. 6 2.2 Vulnerability profile ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Displacement profile ................................................................................................................ 7 2.2.2 Vulnerability types .................................................................................................................... 7 3. Access to services ...................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Education ...................................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Health ........................................................................................................................................... -

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

MINMAP South-West Region

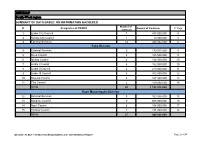

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

Report of Fact-Finding Mission to Cameroon

Report of fact-finding mission to Cameroon Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office United Kingdom 17 – 25 January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preface 1.1 2. Background 2.1 3. Opposition Political Parties / Separatist 3.1. Movements Social Democratic Front (SDF) 3.2 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 3.6 Ambazonian Restoration Movement (ARM) 3.16 Southern Cameroons Youth League (SCYL) 3.17 4. Human Rights Groups and their Activities 4.1 The National Commission for Human Rights and Freedoms 4.5 (NCHRF) Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) 4.10 Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture ………… Nouveaux Droits de l’Homme (NDH) 4.12 Human Rights Defence Group (HRDG) 4.16 Collectif National Contre l’Impunite (CNI) 4.20 5. Bepanda 9 5.1 6. Prison Conditions 6.1 Bamenda Central Prison 6.17 New Bell Prison, Douala 6.27 7. People in Authority 7.1 Security Forces and the Police 7.1 Operational Command 7.8 Government Officials / Public Servants 7.9 Human Rights Training 7.10 8. Freedom of Expression and the Media 8.1 Journalists 8.4 Television and Radio 8.10 9. Women’s Issues 9.1 Education and Development 9.3 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 9.9 Prostitution / Commercial Sex Workers 9.13 Forced Marriages 9.16 Domestic Violence 9.17 10. Children’s Rights 10.1 Health 10.3 Education 10.7 Child Protection 10.11 11. People Trafficking 11.1 12. Homosexuals 12.1 13. Tribes and Chiefdoms 13.1 14. -

Report on the IDB2014 Celebrations in Cameroon

CAMEROON CELEBRATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL DAY FOR BIODIVERSITY Yaounde, Cameroon 14 May 2014 THEME: ISLAND BIODIVERSITY REPORT A cross-section of the exhibition ground including school children and the media Yaounde, 15 May 2014 1 CITATION This document will be cited as MINEPDED 2014. Report on the Celebration of the 2014 International Day for Biodiversity in Cameroon ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The organisation of the 2014 Day for Biodiversity was carried out under the supervision of the Minister of Environment, Protection of Nature and Sustainable Development Mr HELE Pierre and the Minister Delegate Mr. NANA Aboubacar DJALLOH. The contributions of the Organising Committee were highly invaluable for the success of the celebration of the 2014 International Day for Biodiversity. Members were: AKWA Patrick- Secretary General of MINEPDED- Representative of the Minister at the celebration; GALEGA Prudence- National Focal Point for the Convention on Biological Diversity- coordinator of the celebration; WADOU Angele- Sub-Director of Biodiversity and Biosafety, MINEPDED; WAYANG Raphael- Chief of Service for Biodiversity, MINEPDED NFOR Lilian- Environmental Lawyer at the Service of the Technical Adviser No1 of MINEPDED; SHEI Wilson- Project Assistant, ABS; NDIFOR Roland -Representative of IUCN- Cameroon; BANSEKA Hycinth- Representative of Global Water Partnership- Cameroon MBE TAWE Alex- Representative of World Fish Centre- Cameroon 2 TABLE of CONTENT Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………....4 Preparatory activities………………………………………………………………………..5 Media activities………………………………………………………………………………….5 Commemoration of activities…………………………………………………………….6 Exhibition………………………………………………………………………………………....7 Presentation of stands……………………………………………………………………….7 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………12 Photo gallery…………………………………………………………………………………….13 3 INTRODUCTION Cameroon as a member of the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity joined the international community to celebrate the International Day for Biodiversity 2014 under the theme ‘Island Biodiversity”. -

MINMAP Région Du Littoral

MINMAP Région du Littoral SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine d'Edéa 6 1 747 550 008 3 2 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 10 534 821 000 4 TOTAL 16 2 282 371 008 Département du Wouri 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 246 700 000 5 4 Commune de Douala 1 9 370 778 000 5 5 Commune de Douala 2 9 752 778 000 6 6 Commune de Douala 3 12 273 778 000 8 7 Commune de Douala 4 10 278 778 000 9 8 Commune de Douala 5 10 204 605 268 10 9 Commune de Douala 6 10 243 778 000 11 TOTAL 66 2 371 195 268 Département du Moungo 10 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 159 560 000 12 11 Commune de Bare Bakem 9 234 893 804 13 12 Commune de Bonalea 11 274 397 840 14 13 Commune de Dibombari 11 267 278 000 15 14 Commune de Loum 12 228 397 903 16 15 Commune de Manjo 8 160 940 286 18 16 Commune de Mbanga 10 228 455 858 19 17 Commune de Melong 17 291 778 000 20 18 Commune de Njombe Penja 17 427 728 000 21 19 Commune d'Ebone 10 190 778 000 23 20 Commune de Mombo 9 163 878 000 24 21 Commune de Nkongsamba I 7 161 000 000 25 22 Commune de Nkongsamba II 6 172 768 640 25 23 Commune de Nkongsamba III 9 195 278 000 26 TOTAL 146 3 157 132 331 Département de la Sanaga Maritime 24 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 214 167 000 27 25 Commune de Dibamba 14 358 471 384 28 26 Commune de Dizangue 13 252 678 000 29 27 Commune de Massock 16 319 090 512 30 28 Commune de Mouanko 9 251 001 000 31 29 Commune de Ndom 17 340 778 000 31 30 Commune de Ngambe 9 235