South West Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

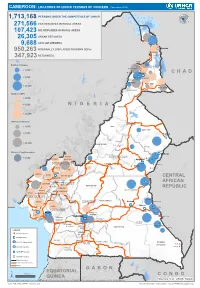

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights • From 25-27 April, Marie-Pierre Poirier, UNICEF Regional Director April 2018 for West and Central Africa Region visited projects in the Far North and East regions to evaluate the humanitarian situation 1,810,000 # of children in need of humanitarian and advocated for the priorities for children, including birth assistance registrations. 3,260,000 • UNHCR and UNICEF with support of WFP donated 30 tons of non- # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2018) food items including soaps to be distributed in Mamfe and Kumba sub-divisions in South West region for estimated 23,000 people Displacement affected by the Anglophone crisis. 241,000 • As part of the development of an exit strategy for Temporary #of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) Learning and Protective Spaces (TLPSs), a joint mission was 69,700 conducted to verify the situation of 87 TLPSs at six refugee sites # of Returnees and host community schools in East and Adamaoua regions. The (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) 93,100 challenge identified is how to accommodate 11,314 children who # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas are currently enrolled in the TLPSs into only 11 host community (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) 238,700 schools, with additional 7,325 children (both IDPs and host # of CAR Refugees in East, Adamaoua and community) expected to reach the school age in 2018. North regions in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) UNICEF’s Response with Partners UNICEF Appeal 2018 Sector UNICEF US$ 25.4 million Sector Total UNICEF Total Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH : People provided with 528,000 8,907 75,000 8,907 US$ 2.1 m access to appropriate sanitation Funds Education: School-aged children 4- received 17, including adolescents, accessing 411,000 11,314 280,000 11,314 US$ 1.8 m education in a safe and protective learning environment. -

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

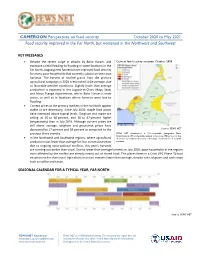

CAMEROON Perspectives on Food Security October 2020 to May 2021 Food Security Improved in the Far North, but Worsened in the Northwest and Southwest

CAMEROON Perspectives on food security October 2020 to May 2021 Food security improved in the Far North, but worsened in the Northwest and Southwest KEY MESSAGES • Despite the recent surge in attacks by Boko Haram, and Current food security situation, October 2020 excessive rainfall leading to flooding in some locations in the Far North, ongoing new harvests have improved food security for many poor households that currently subsist on their own harvests. The harvest of rainfed grains from the primary agricultural campaign in 2020 is estimated to be average, due to favorable weather conditions. Slightly lower than average production is expected in the Logone-et-Chari, Mayo Sava, and Mayo Tsanga departments, where Boko Haram is most active, as well as in locations where harvests were lost to flooding. • Current prices at the primary markets in the Far North appear stable or are decreasing. Since July 2020, staple food prices have increased above typical levels. Sorghum and maize are selling at 46 to 60 percent, and 30 to 47 percent higher (respectively) than in July 2019. Although current prices are still above average, sorghum and groundnut prices have decreased by 17 percent and 18 percent as compared to the Source: FEWS NET previous three months. FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible (Integrated Phase Classification). IPC-compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but • In the Northwest and Southwest regions, where agricultural does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national food security production was lower than average for four consecutive years partners. due to ongoing socio-political conflicts, this year's harvests are running out earlier than usual. -

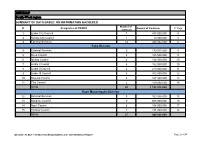

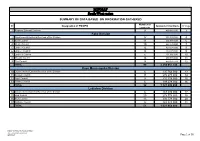

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

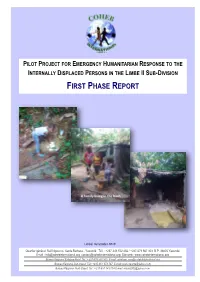

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST