What Are the Similarities and Differences Among English Language, Foreign Language, and Heritage Language Education in the United States?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

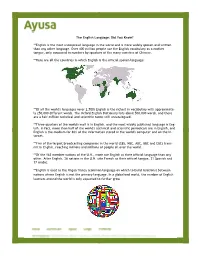

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Diversifying Language Educators and Learners by Uju Anya and L

Powerful Voices Diversifying Language Educators and Learners By Uju Anya and L. J. Randolph, Jr. EDITOR’S NOTE: Want to discuss this topic further? Log on and head over to The Language Educator Magazine In this issue we present articles on the Focus Topic group in the ACTFL Online Community “Diversifying Language Educators and Learners.” The (community.actfl.org). submissions for this issue were blind reviewed by three education experts, in addition to staff from The Language Educator and ACTFL. We thank Uju Anya, Assistant Professor of Second Language Learning and Research Affiliate with the Center for the Study of Higher Education at The Pennsylvania State University College of Education, University Park, PA, and L. J. Randolph Jr., Associate Chair of the Department of World Languages and Cultures Along with not limiting the definition of diversity to a single and Associate Professor of Spanish and Education at the meaning, we also resist defining it as the mere presence of University of North Carolina Wilmington, for writing an individuals with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and identi- introduction to this important topic. ties. Such an approach amounts to little more than tokenism, because it focuses on counting people from different social categories without much thought to their inclusion, impact, interactions, and contributions. Instead, we think of diversity he word “diversity” is both necessary and challenging. It is in terms of equitable, meaningful representation and participa- necessary, because to ignore diversity is to reinforce legacies tion. This notion of diversity, as described by Fosslien and West T of inequity and exclusion upon which our educational insti- Duffy (2019), is the difference between saying that everyone tutions were built. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Supporting Digital Learning Across Language Communities in Wales

Modern Languages and Mentoring: Supporting Digital Learning across Language Communities in Wales Authors: Claire Gorrara, Lucy Jenkins and Neil Mosley Image: Scarlet Design Limited Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project Open World Research Initiative (OWRI): Multilingualism: Empowering Individuals, Transforming Societies (MEITS) for their support and for funding this report. The authors would also like to thank the following for their support and expertise in aiding the development of the MFL Student Mentoring and the Digi-Languages projects: Sally Blake, Head Mentor Trainer Anna Vivian-Jones, ERW Consortia Lead for MFL Amy Walters-Bresner, CSC Consortia Lead for MFL Sioned Harold, EAS Consortia Lead for MFL Sylvie Gartau, GwE Consortia Lead for MFL Nicola Giles, Lead for Global Futures, Welsh Government Peter Thomas, Hwb, Welsh Government Cardiff University’s Centre of Education and Innovation (CEI) Tallulah Machin, Chief Student Mentor Emma Dawson-Varughese, Independent Consultant Elen Davies, WJEC Image: Scarlet Design Limited. Modern Languages and Mentoring: Supporting Digital Learning across Language Communities in Wales by Claire Gorrara, Lucy Jenkins and Neil Mosley All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication without prior written permission. The rights of Claire Gorrara, Lucy Jenkins and Neil Mosley to be identified as the authors of this report have been asserted with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by School of Modern Languages, Cardiff University. 1 Executive Summary This report considers the role that mentoring, and in particular online mentoring, can play in tackling the decline in modern foreign languages learning at GCSE level in Wales. -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

The Arabic Language in Israel: Official Language, Mother Tongue, Foreign Language

The Arabic Language in Israel: official language, mother tongue, foreign language. Teaching, dissemination and competence by Letizia Lombezzi INTRODUCTION: THE STATE OF ISRAEL, SOME DATA1 The analysis of the linguistic situation in the state of Israel cannot set aside a glance at the geography of the area, and the composition of the population. These data are presented here as such and without any interpretation. Analysis, opinion and commentary will instead be offered in the following sections and related to the Arabic language in Israel that is the focus of this article. 1 From “The World Factbook” by CIA, <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world- factbook/> (10 September 2016). The CIA original survey dates back to 2014; it has recently been updated with new data. In those cases, I indicated a different date in brackets. Saggi/Ensayos/Essais/Essays CONfini, CONtatti, CONfronti – 02/2018 248 Territory: Area: 20,770 km2. Borders with Egypt, 208 km; with the Gaza Strip, 59 km; with Jordan 307 km; with Lebanon 81 km; 83 km with Syria; with The West Bank 330 km. Coast: 273 km. Settlements in the occupied territories: 423, of which: 42 in the Golan Heights; 381 sites in the occupied Palestinian territories, among them: 212 settlements and 134 outposts in the West Bank; 35 settlements in East Jerusalem. Population: Population: 8,049,314 (data of July 2015). These include the population of the Golan, around 20,500 people and in East Jerusalem, about 640 people (data of 2014). Mean age 29.7 years (29.1 M, F 30.4, the 2016 data). -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

New Zealand Ways of Speaking English Edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77n0788f Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 2(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Locker, Rachel Publication Date 1991-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L421005133 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REVIEWS New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Reviewed by Rachel Locker University of California, Los Angeles Coming to America has resulted in an interesting encounter with my linguistic identity, my New Zealand accent regularly provoking at least two distinct reactions: either "Please say something, I love the way you talk!" (which causes me some amusement but mainly disbelief), or "Your English is very good- what's your native language?" It is difficult to review a book like New Zealand Ways of Speaking English without relating such experiences, because as a nation New Zealanders at home and abroad have long suffered from a lurking sense of inferiority about the way they speak English, especially compared with those in the colonial "homeland," i.e., England. That dialectal differences create attitudes about what is better and worse is no news to scholars of language use, but this collection of studies on New Zealand English (NZE) not only reveals some interesting peculiarities of that particular dialect and its speakers from "down- under"; it also makes accessible the significant contributions of New Zealand linguists to broader theoretical concerns in sociolinguistics and applied linguistics. -

Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF Latl'er-Qt.Y SAINTS

GENEALOGICAL WORD LIST ~ Afrikaans FAMILY HISTORY LIBRARY" SALTLAKECITY, UTAH TMECHURCHOF JESUS CHRISTOF LATl'ER-Qt.y SAINTS This list contains Afrikaans words with their English these compound words are included in this list. You translations. The words included here are those that will need to look up each part of the word separately. you are likely to find in genealogical sources. If the For example, Geboortedag is a combination of two word you are looking for is not on this list, please words, Geboorte (birth) and Dag (day). consult a Afrikaans-English dictionary. (See the "Additional Resources" section below.) Alphabetical Order Afrikaans is a Germanic language derived from Written Afrikaans uses a basic English alphabet several European languages, primarily Dutch. Many order. Most Afrikaans dictionaries and indexes as of the words resemble Dutch, Flemish, and German well as the Family History Library Catalog..... use the words. Consequently, the German Genealogical following alphabetical order: Word List (34067) and Dutch Genealogical Word List (31030) may also be useful to you. Some a b c* d e f g h i j k l m n Afrikaans records contain Latin words. See the opqrstuvwxyz Latin Genealogical Word List (34077). *The letter c was used in place-names and personal Afrikaans is spoken in South Africa and Namibia and names but not in general Afrikaans words until 1985. by many families who live in other countries in eastern and southern Africa, especially in Zimbabwe. Most The letters e, e, and 0 are also used in some early South African records are written in Dutch, while Afrikaans words. -

Introduction to the History of the English Language

INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE Written by László Kristó 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 NOTES ON PHONETIC SYMBOLS USED IN THIS BOOK ................................................. 5 1 Language change and historical linguistics ............................................................................. 6 1.1 Language history and its study ......................................................................................... 6 1.2 Internal and external history ............................................................................................. 6 1.3 The periodization of the history of languages .................................................................. 7 1.4 The chief types of linguistic change at various levels ...................................................... 8 1.4.1 Lexical change ........................................................................................................... 9 1.4.2 Semantic change ...................................................................................................... 11 1.4.3 Morphological change ............................................................................................. 11 1.4.4 Syntactic change ...................................................................................................... 12 1.4.5 Phonological change .............................................................................................. -

Of Languages

INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION RESEARCH FOUNDATION ® Index of Languages Français Türkçe 日本語 English Pусский Nederlands Português中文Español Af-Soomaali Deutsch Tiếng Việt Bahasa Melayu Ελληνικά Kiswahili INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION RESEARCH FOUNDATION ® P.O. Box 3665 Culver City, CA 90231-3665 Phone: 310.258.9451 Fax: 310.342.7086 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ierf.org 1969-2017 © 2017 International Education Research Foundation (IERF) Celebrating 48 years of service Index of Languages IERF is pleased to present the Index of Languages as the newest addition to The New Country Index series. as established as a not-for-profit, public-benefit agency This helpful guide provides the primary languages of instruction for over 200 countries and territories around but also in the world. Inez Sepmeyer and the world. It highlights not only the medium of instruction at the secondary and postsecondary levels, but also , respectively, identifies the official language(s) of these regions. This resource, compiled by IERF evaluators, was developed recognized the need for assistance in the placement of international students and professionals. In 1969, IERF as a response to the requests that we receive from many of our institutional users. These include admissions officers, registrars and counselors. A bonus section has also been added to highlight the examinations available to help assess English language proficiency. Using ation of individuals educated I would like to acknowledge and thank those IERF evaluators who contributed to this publication. My sincere . gratitude also goes to the editors for their hard work, energy and enthusiasm that have guided this project. Editors: Emily Tse Alice Tang profiles of 70 countries around the Contributors: Volume I.