After the Fact the ART of HISTORICAL DETECTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greensboro Sit-Ins

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > Greensboro Sit-Ins Greensboro Sit-Ins [1] Share it now! Greensboro Sit-Ins by Alexander R. Stoesen, 2006 See also: Greensboro Four [2], Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [3]. Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Billy Smith and Clarence Henderson. Greensboro News and Record. The Greensboro [4] sit-ins of February 1960 launched the movement to integrate lunch counters and other eating establishments throughout North Carolina and the rest of the South. Sit-ins [5] had previously occurred in other places, but the Greensboro protests sparked widespread activism and media attention. The sit-ins began when four students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University [6]—Ezell A. Blair [7] (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin E. McCain [8], Joseph A. McNeil [9], and David L. Richmond [10]—sat at the lunch counter of the Woolworth Store on Elm Street in Greensboro late on the afternoon of 1 Feb. 1960. At the time, Woolworth's only served African Americans [11] at a stand-up counter. Instead of having the students arrested for trespassing, the manager closed the lunch counter, intending to leave them stranded at closing time. The Greensboro store, one of the most profitable in the region, had a large black clientele-hence the need for prudence. However, by not filing charges, the manager left an opening for further nonviolent action. The next day, the number of demonstrators grew rapidly, and in the days and weeks that followed, sit-ins spread to other eating places in Greensboro's central business district. Some managers closed their operations, but by the end of the summer an agreement had been reached to end segregation [12] in public eating places. -

Have a Seat to Be Heard: the Sit-In Movement of the 1960S

(South Bend, IN), Sept. 2, 1971. Have A Seat To Be Heard: Rodgers, Ibram H. The Black Campus Movement: Black Students The Sit-in Movement Of The 1960s and the Racial Reconstih,tion ofHigher Education, 1965- 1972. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. "The Second Great Migration." In Motion AAME. Accessed April 9, E1~Ai£-& 2017. http://www.inmotion.org/print. Sulak, Nancy J. "Student Input Depends on the Issue: Wolfson." The Preface (South Bend, IN), Oct. 28, 1971. "If you're white, you're all right; if you're black, stay back," this derogatory saying in an example of what the platform in which seg- Taylor, Orlando. Interdepartmental Communication to the Faculty regation thrived upon.' In the 1960s, all across America there was Council.Sept.9,1968. a movement in which civil rights demonstrations were spurred on by unrest that stemmed from the kind of injustice represented by United States Census Bureau."A Look at the 1940 Census." that saying. Occurrences in the 1960s such as the Civil Rights Move- United States Census Bureau. Last modified 2012. ment displayed a particular kind of umest that was centered around https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/194ocensus/ the matter of equality, especially in regards to African Americans. CSP AN_194oslides. pdf. More specifically, the Sit-in Movement was a division of the Civil Rights Movement. This movement, known as the Sit-in Movement, United States Census Bureau. "Indiana County-Level Census was highly influenced by the characteristics of the Civil Rights Move- Counts, 1900-2010." STATSINDIANA: Indiana's Public ment. Think of the Civil Rights Movement as a tree, the Sit-in Move- Data Utility, nd. -

Congressional Record—House H572

H572 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE January 28, 2020 regulated. Ninety-nine percent of The four young men—Ezell Blair, Jr.; ing Woolworth’s and other establish- Pennsylvania was swept under these David Richmond; Franklin McCain; ments to change their discriminatory overreaching WOTUS regulations. and Joseph McNeil—were students policies. On July 26, 1960, the Wool- In addition to taking away States’ from North Carolina A&T College, now worth’s lunch counter was finally inte- authority to manage water resources, known as North Carolina A&T State grated. Today, the former Woolworth’s the 2015 WOTUS rule expanded the University. I might add that A&T now houses the International Civil Clean Water Act far beyond the law’s State University is now the largest Rights Center and Museum, which fea- historical limits of navigable waters HBCU in the country. tures a restored version of the lunch and the long-held intent of Congress. Mr. Speaker, I would also mention counter where the Greensboro Four Instead of providing much-needed clar- that Congresswoman ALMA ADAMS is a sat. Part of the original counter is on ity to the Clean Water Act, WOTUS graduate of A&T State University and display at the Smithsonian National created even more confusion. served as a college professor across the Museum of American History here in Thankfully, the negative impact of street at Bennett College for more than Washington. WOTUS was brought to an end when 40 years. On Saturday of this week, February the Trump administration repealed it The Greensboro Four students were 1, the museum will commemorate the this past fall. -

NC A&T State University

NC A&T State University State A&T NC 15 WOMEN'S BASKETBALL NNCC A&T StateState UUniversityniversity Throughout the years North Carolina A&T State University’s elite academic programs have led to pioneers in the areas of politics, media, business, engineering, sports the Armed Services. Become an Aggie and watch your goals realized. Whether it is running for president, being an executive for a pro franchise or hosting a popular television show, N.C. A&T offers tremendous opportunities for its student population. N.C. A&T has a lot to offer beyond the typical classroom setting. The large variety of student organizations, intramural sports and leadership opportunities foster excellence and make for an unforgettable and rewarding college experience. Lasting friendships are created through participation in athletics, Greek life, the A&T student newspaper (A&T Register), WNAA 90.1 FM, Blue & Gold Marching Machine, ROTC and much, much more. Unlike other campuses, where students are randomly assigned to residence halls, at N.C. A&T you can choose from 13 different halls including traditional rooms, suites, and two or four bedroom apartments. Currently, more than 4,000 students take advantage of the convenience and community of campus life. INNOVATIVE, CREATIVE AND DEDICATED N.C. A&T is the nation’s No. 1 producer of minorities with degrees in science, mathematics, engineering and technology. Aggieland is the third largest producer of African-American engineers with master’s degrees and it is a leading producer of African-American engineers with doctorate degrees. Females comprise approximately 30 percent of the students in the College of Engineering, thus ranking the college sixth in the country in the percentage of degrees awarded to women. -

A&T Four Box 0002

Inventory of the A&T Four Collection, Box 002 Contact Information Archives and Special Collections F.D. Bluford Library North Carolina A&T State University Greensboro, NC 27411 Telephone: 336-285-4176 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ncat.edu/resources/archives Descriptive Summary Repository F. D. Bluford Library Archives and Special Collections Creator Franklin McCain Ezell Blair, Jr. (Jibreel Khazan) David Richmond, Sr. Joseph Mc Neil Title “A&T Four” Box #2 Language of Materials English Extent 1 archival boxes, 121 items, 1.75 linear feet Abstract The Collection consists Events programs and newspaper articles and editorials commemorating the 1960 sit-ins over the years from 1970s to 2000s. The articles cover how A&T, Greensboro and the nation honor the Four and the sit-in movement and its place in history. They also put it in context of racial relations contemporary with their publication. Administrative Information Restrictions to Access No Restrictions Acquisitions Information Please consult Archives Staff for additional information. Processing Information Processed by James R. Jarrell, April 2005; Edward Lee Love, Fall 2016. Preferred Citation [Identification of Item], in the A&T Four Box 2, Archives and Special Collections, Bluford Library, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Greensboro, NC. Copyright Notice North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College owns copyright to this collection. Individuals obtaining materials from Bluford Library are responsible for using the works in conformance with United State Copyright Law as well as any restriction accompanying the materials. Biographical Note On February 1, 1960, NC A&T SU freshmen Franklin McCain, David Richmond, Joseph McNeil, and Ezell Blair (Jibreel Khazan) sat down at the whites only lunch counter at the F.W. -

1960: the Greensboro Sit

1960: The Greensboro Sit Ins When Four students sat down at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., over 50 years ago, they helped re- ignite the Civil Rights Movement By Suzanne Bilyeu It was shortly after four in the afternoon when four college freshmen entered the Woolworth's store in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. They purchased a few small items—school supplies, toothpaste—and were careful to keep their receipts. Then they sat down at the store's lunch counter and ordered coffee. "I'm sorry," said the waitress. "We don't serve Negroes here." "I beg to differ," said one of the students. He pointed out that the store had just served them—and accepted their money—at a counter just a few feet away. They had the receipts to prove it. A black woman working at the lunch counter scolded the students for trying to stir up trouble, and the store manager asked them to leave. But the four young men sat quietly at the lunch counter until the store closed at 5:30. Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond, now known as the "Greensboro Four," were all students at North Carolina A&T (Agricultural and Technical) College, a black college in Greensboro. They were teenagers, barely out of high school. But on that Monday afternoon, Feb. 1, 1960, they started a movement that changed America. A Decade of Protest The Greensboro sit-in 50 years ago, and those that followed, ignited a decade of civil rights protests in the U.S. It was a departure from the approach of the N.A.A.C.P. -

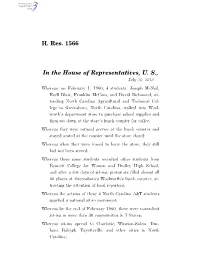

H. Res. 1566 in the House of Representatives, U

H. Res. 1566 In the House of Representatives, U. S., July 30, 2010. Whereas, on February 1, 1960, 4 students, Joseph McNeil, Ezell Blair, Franklin McCain, and David Richmond, at- tending North Carolina Agricultural and Technical Col- lege in Greensboro, North Carolina, walked into Wool- worth’s department store to purchase school supplies and then sat down at the store’s lunch counter for coffee; Whereas they were refused service at the lunch counter and stayed seated at the counter until the store closed; Whereas when they were forced to leave the store, they still had not been served; Whereas these same students recruited other students from Bennett College for Women and Dudley High School, and after a few days of sit-ins, protestors filled almost all 66 places at Greensboro’s Woolworth’s lunch counter, at- tracting the attention of local reporters; Whereas the actions of these 4 North Carolina A&T students sparked a national sit-in movement; Whereas by the end of February 1960, there were nonviolent sit-ins in more than 30 communities in 7 States; Whereas sit-ins spread to Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Dur- ham, Raleigh, Fayetteville, and other cities in North Carolina; 2 Whereas on February 9, students at Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina, instituted numerous sit-ins with Friendship Junior College students in Rock Hill, South Carolina; Whereas most Charlotte lunch counters and restaurants even- tually integrated their businesses; Whereas North and South Carolina students protested seg- regation in Rock Hill, South Carolina, -

February One

February One Documentary Film Study Guide By Rebecca Cerese & Diane Wright Available online at www.newsreel.org Film Synopsis Greensboro, North Carolina, was a fairly typical Southern city in the middle of the 20th Century. The city was certainly segregated, but city officials prided themselves on handling race relations with more civility than many other Southern cities. Ezell Blair, Jr. (who later changed his name to Jibreel Khazan) was the son of an early member of the NAACP, who introduced him to the idea of activism at an early age. Ezell attended segregated Dudley High School, where he befriended Franklin McCain. Franklin, raised in the more racially open city of Washington, DC, was angered by the segregation he encountered in Greensboro. Ezell and Franklin became fast friends with David Richmond, the most popular student at Dudley High. In 1958, Ezell and David heard Martin Luther King, Jr., speak at Bennett College in Greensboro. At the same time, the rapid spread of television was bringing images of oppression and conflict from around the world into their living rooms. Ezell was inspired by the non-violent movement for independence led by Mahatma Gandhi and chilled by the brutal murder of Emmett Till. In the fall of 1959, Ezell, Franklin, and David enrolled in Greensboro’s all-black college, North Carolina A&T State University. Ezell’s roommate was Joseph McNeil, an idealistic young man from New York City. Ezell, Franklin, David, and Joseph became a close-knit group and got together for nightly bull sessions in their dorm rooms. During this time they began to consider challenging the institution of segregation. -

Virginia Tech Conductor

March 3, 2006 Virginia Tech Conductor A GUIDE FOR OUR JOURNEY TOWARD EXCELLENCE, EQUITY AND EFFECTIVENESS A tribute to Dr. Giovanni hits NY Times best-seller list King, Jr. By Jean Elliott Hazel Rochman, of the American Library Association said in her by Takiyah Nur Amin © 2006 Rosa, written by Virginia Tech’s Nikki review, “The history comes clear in the astonishing combination of the “If I Can Help, Then Giovanni, rocketed to number three in the NY personal and the political.” My Living Will Times Children’s Book List in early February. Not Be In Vain…” Rosa, published by Henry Holt and Company Notes from Nikki… …and it’s like he never and vibrantly illustrated by Bryan Collier, tells In an early December interview with NPR’s Ed Gordon, Giovanni left us. the story of Rosa Parks, a seamstress from discussed how she wanted to portray Mrs. Parks, a woman she had Dreams become cliché Montgomery, Alabama, who refused to give up known personally for 24 years. “I wanted to share the woman that I had and deferred while her seat on a bus. This action sparked protests the privilege of knowing with younger people. Mrs. Parks was an icon, love eludes us and and ignited the civil rights movement. and when you’ve become iconic, you’re bigger than life. I wanted to freedom can’t be found A University Distinguished Professor in the Department of show that she was an ordinary woman who did an extraordinary thing,” But, English, Giovanni’s book has been universally well received by the said Giovanni. -

A Major Aspect of the 1960 Sit-In Movement Is That It Was Led by Young African Americans. This Generation Grew up Cl

Background: About the eLearning: A major aspect of the 1960 Sit-In Movement is that it was led by young African Americans. This generation grew up closely watching the gains made by their elders during the 1950s—like the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Brown v Board of Education—but were left perplexed and dismayed by how little had changed. African Americans were still subject to the daily grinding and dehumanizing effects of a discriminatory social structure. Schools in particular remained segregrated and unequal. Young African Americans Standing Up by Sitting Down is an interpretation navigated the same Jim Crow rules that of the exhibit by the same name at the National previous generations had endured. The new Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. The generation of 1960 had had enough and eLearning follows the movement sequentially and chose to risk everything to act against the highlights key personalities like the A&T Four, Diane status quo. Nash and Ella Baker. Screen elements elicit your students’ viewpoints along the way culminating in a The resulting student leaders would impact printable summary that can be used as a classroom virtually every aspect of the US Civil Rights assignment. movement from that point on. Civil Rights luminaries like Diane Nash, John Lewis, Incorporating the eLearning activity into a Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, David Lesson Plan: Richmond, Ezell Blair, Stokely Carmichael The eLearning can be assigned as homework or and many others were students in 1960 conducted as classroom activity using a projector. and would loom large in the sit-ins, SNCC (the Student Non-violient Coordinating Throughout the eLearning, students are asked to rate Committee), the Freedom Rides, and beyond. -

NA Boyer Ch 28.V1

CHAPTER 28 The Liberal Era, 1960–1968 n the afternoon of February 1, 1960, four students at North Carolina OAgricultural and Technical (A&T) College in Greensboro—Ezell Blair, Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond—entered the local Woolworth’s and sat down at the whites-only lunch counter. “We don’t serve colored here,” the waitress replied when the freshmen asked for coffee and doughnuts. The black students remained seated. They would not be moved. Middle class in aspirations, the children of urban civil servants and industrial workers, they believed that the Supreme Court’s Brown decision of 1954 should have ended the indignities of racial discrimination and segregation. But the promise of change had outrun reality. Massive resistance to racial equality still proved the rule throughout Dixie. In 1960 most southern blacks could neither vote nor attend integrated schools. They could not enjoy a cup of coffee alongside whites in a public restaurant. Impatient yet hopeful, the A&T students could not accept the inequality their parents had endured. They had been inspired by the Montgomery bus boy- CHAPTER OUTLINE cott led by Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as by successful African independence The Kennedy Presidency, 1960–1963 movements in the late 1950s. They vowed to sit in until the store closed and to repeat their request the next day and beyond, until they were served. Liberalism Ascendant. 1963–1968 On February 2 more than twenty A&T students joined them in their The Struggle for Black Equality, protest. The following day, over sixty sat in. -

International Civil Rights Center & Museum

★ Celebrate Greensboro art. Culture. Entertainment. By Tara TiTcomBe A movement that inspired the nation The International Civil Rights Center & Museum must-see vital piece of history stands and the following with more in the center of downtown Greensboro, than 300. By the end of that March, similar protests were welcoming and educating all who visit. taking place in more than The International Civil Rights Center 55 cities and 13 states. The & Museum tells the story of the non- non-violent sit-in movement was born, and the nation would tre violent civil rights movement that be- never be the same. A the gan 51 years ago in its very location. Today the International A rolin Civil Rights Center & A Museum, housed in the former the c M F AOn February 1, 1960, four African-American Woolworth store in downtown Greensboro, freshmen from Greensboro’s N.C. A&T State celebrates that moment in history and University sat down at the F.W. Woolworth remains devoted to the global struggle for enter & Museu c store’s “whites only” civil and human rights. ights r Visit, ExplorE , Learn lunch counter and The two-floor, 43,000-square-foot ivil c For more information on Greensboro’s ordered coffee. They museum opened on February 1, 2010 — l A International Civil Rights Center & were denied service, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the tion A Museum, stop by 134 South Elm St., call nd (right) Andy Ferrell/courtesy o 336 . 274.9199 or 800.748 .7 116, or check ignored, then asked to sit-ins.