Freedom Is Never Free!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acoa 0 0 0 0

AMERICAN COMMITrEE ON AFRICA - 198 Broadway * New York, N.Y. 10038 * (212) 962-1210 AMERICAN COMMITrEE ON AFRICA - 198 Broadway * New York, N.Y. 10038 * (212) 962-1210 A QUARTER CENTURY OF STRUGGLE By William Booth President, ACOA On July 1st, George M. Houser will retire from the American Committee on Africa, having served as executive director since 1955. Leadership will be handed on to his colleague of many years, research director Jennifer Davis. It gives me great pleasure to take this opportunity to recall George's achievements and to welcome Jennifer as the new director. George Houser arrived in Luanda this April the very day that the leaders of the Front Line States were meeting thereto discuss Namibia's future. He spent two hours with Angolan Foreign Minister Paulo Jorge the night before the Foreign Minister met with Chester Crocker, Assistant Secretary of Statedesignate for African Affairs. Being in the right place at the right time is something George Houser has been doing for more than twenty five years. He was in Addis Ababa in 1963 when the Organization of African Unity was founded, and in Ghana in 1954 and Zimbabwe in 1980 when important elections were held in those two countries. He attended the All African People's Conference in 1958, 1960, and 1961, meeting Patrice Lumumba, Tom Mboya, Kwame Nkrumah and many others. George met Nkrumah on his first trip to Africa in 1954, and ACOA helped sponsor a dinner in his honor in 1958 which was attended by 1100 people. Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere were among numerous other leaders who ACOA invited to the US to speak or assisted as they came to the UN to petition. -

Greensboro Sit-Ins

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > Greensboro Sit-Ins Greensboro Sit-Ins [1] Share it now! Greensboro Sit-Ins by Alexander R. Stoesen, 2006 See also: Greensboro Four [2], Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [3]. Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Billy Smith and Clarence Henderson. Greensboro News and Record. The Greensboro [4] sit-ins of February 1960 launched the movement to integrate lunch counters and other eating establishments throughout North Carolina and the rest of the South. Sit-ins [5] had previously occurred in other places, but the Greensboro protests sparked widespread activism and media attention. The sit-ins began when four students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University [6]—Ezell A. Blair [7] (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin E. McCain [8], Joseph A. McNeil [9], and David L. Richmond [10]—sat at the lunch counter of the Woolworth Store on Elm Street in Greensboro late on the afternoon of 1 Feb. 1960. At the time, Woolworth's only served African Americans [11] at a stand-up counter. Instead of having the students arrested for trespassing, the manager closed the lunch counter, intending to leave them stranded at closing time. The Greensboro store, one of the most profitable in the region, had a large black clientele-hence the need for prudence. However, by not filing charges, the manager left an opening for further nonviolent action. The next day, the number of demonstrators grew rapidly, and in the days and weeks that followed, sit-ins spread to other eating places in Greensboro's central business district. Some managers closed their operations, but by the end of the summer an agreement had been reached to end segregation [12] in public eating places. -

Have a Seat to Be Heard: the Sit-In Movement of the 1960S

(South Bend, IN), Sept. 2, 1971. Have A Seat To Be Heard: Rodgers, Ibram H. The Black Campus Movement: Black Students The Sit-in Movement Of The 1960s and the Racial Reconstih,tion ofHigher Education, 1965- 1972. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. "The Second Great Migration." In Motion AAME. Accessed April 9, E1~Ai£-& 2017. http://www.inmotion.org/print. Sulak, Nancy J. "Student Input Depends on the Issue: Wolfson." The Preface (South Bend, IN), Oct. 28, 1971. "If you're white, you're all right; if you're black, stay back," this derogatory saying in an example of what the platform in which seg- Taylor, Orlando. Interdepartmental Communication to the Faculty regation thrived upon.' In the 1960s, all across America there was Council.Sept.9,1968. a movement in which civil rights demonstrations were spurred on by unrest that stemmed from the kind of injustice represented by United States Census Bureau."A Look at the 1940 Census." that saying. Occurrences in the 1960s such as the Civil Rights Move- United States Census Bureau. Last modified 2012. ment displayed a particular kind of umest that was centered around https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/194ocensus/ the matter of equality, especially in regards to African Americans. CSP AN_194oslides. pdf. More specifically, the Sit-in Movement was a division of the Civil Rights Movement. This movement, known as the Sit-in Movement, United States Census Bureau. "Indiana County-Level Census was highly influenced by the characteristics of the Civil Rights Move- Counts, 1900-2010." STATSINDIANA: Indiana's Public ment. Think of the Civil Rights Movement as a tree, the Sit-in Move- Data Utility, nd. -

Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation

09-Mollin 12/2/03 3:26 PM Page 113 The Limits of Egalitarianism: Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation Marian Mollin In April 1947, a group of young men posed for a photograph outside of civil rights attorney Spottswood Robinson’s office in Richmond, Virginia. Dressed in suits and ties, their arms held overcoats and overnight bags while their faces carried an air of eager anticipation. They seemed, from the camera’s perspective, ready to embark on an exciting adventure. Certainly, in a nation still divided by race, this visibly interracial group of black and white men would have caused people to stop and take notice. But it was the less visible motivations behind this trip that most notably set these men apart. All of the group’s key organizers and most of its members came from the emerging radical pacifist movement. Opposed to violence in all forms, many had spent much of World War II behind prison walls as conscientious objectors and resisters to war. Committed to social justice, they saw the struggle for peace and the fight for racial equality as inextricably linked. Ardent egalitarians, they tried to live according to what they called the brotherhood principle of equality and mutual respect. As pacifists and as militant activists, they believed that nonviolent action offered the best hope for achieving fundamental social change. Now, in the wake of the Second World War, these men were prepared to embark on a new political jour- ney and to become, as they inscribed in the scrapbook that chronicled their traveling adventures, “courageous” makers of history.1 Radical History Review Issue 88 (winter 2004): 113–38 Copyright 2004 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963

SUTTELL, BRIAN WILLIAM, Ph.D. Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963. (2017) Directed by Dr. Charles C. Bolton. 296 pp. This work investigates civil rights activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, in the early 1960s, especially among students at Shaw University, Saint Augustine’s College (Saint Augustine’s University today), and North Carolina College at Durham (North Carolina Central University today). Their significance in challenging traditional practices in regard to race relations has been underrepresented in the historiography of the civil rights movement. Students from these three historically black schools played a crucial role in bringing about the end of segregation in public accommodations and the reduction of discriminatory hiring practices. While student activists often proceeded from campus to the lunch counters to participate in sit-in demonstrations, their actions also represented a counter to businesspersons and politicians who sought to preserve a segregationist view of Tar Heel hospitality. The research presented in this dissertation demonstrates the ways in which ideas of academic freedom gave additional ideological force to the civil rights movement and helped garner support from students and faculty from the “Research Triangle” schools comprised of North Carolina State College (North Carolina State University today), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Many students from both the “Protest Triangle” (my term for the activists at the three historically black schools) and “Research Triangle” schools viewed efforts by local and state politicians to thwart student participation in sit-ins and other forms of protest as a restriction of their academic freedom. -

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

Congressional Record—House H572

H572 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE January 28, 2020 regulated. Ninety-nine percent of The four young men—Ezell Blair, Jr.; ing Woolworth’s and other establish- Pennsylvania was swept under these David Richmond; Franklin McCain; ments to change their discriminatory overreaching WOTUS regulations. and Joseph McNeil—were students policies. On July 26, 1960, the Wool- In addition to taking away States’ from North Carolina A&T College, now worth’s lunch counter was finally inte- authority to manage water resources, known as North Carolina A&T State grated. Today, the former Woolworth’s the 2015 WOTUS rule expanded the University. I might add that A&T now houses the International Civil Clean Water Act far beyond the law’s State University is now the largest Rights Center and Museum, which fea- historical limits of navigable waters HBCU in the country. tures a restored version of the lunch and the long-held intent of Congress. Mr. Speaker, I would also mention counter where the Greensboro Four Instead of providing much-needed clar- that Congresswoman ALMA ADAMS is a sat. Part of the original counter is on ity to the Clean Water Act, WOTUS graduate of A&T State University and display at the Smithsonian National created even more confusion. served as a college professor across the Museum of American History here in Thankfully, the negative impact of street at Bennett College for more than Washington. WOTUS was brought to an end when 40 years. On Saturday of this week, February the Trump administration repealed it The Greensboro Four students were 1, the museum will commemorate the this past fall. -

NC A&T State University

NC A&T State University State A&T NC 15 WOMEN'S BASKETBALL NNCC A&T StateState UUniversityniversity Throughout the years North Carolina A&T State University’s elite academic programs have led to pioneers in the areas of politics, media, business, engineering, sports the Armed Services. Become an Aggie and watch your goals realized. Whether it is running for president, being an executive for a pro franchise or hosting a popular television show, N.C. A&T offers tremendous opportunities for its student population. N.C. A&T has a lot to offer beyond the typical classroom setting. The large variety of student organizations, intramural sports and leadership opportunities foster excellence and make for an unforgettable and rewarding college experience. Lasting friendships are created through participation in athletics, Greek life, the A&T student newspaper (A&T Register), WNAA 90.1 FM, Blue & Gold Marching Machine, ROTC and much, much more. Unlike other campuses, where students are randomly assigned to residence halls, at N.C. A&T you can choose from 13 different halls including traditional rooms, suites, and two or four bedroom apartments. Currently, more than 4,000 students take advantage of the convenience and community of campus life. INNOVATIVE, CREATIVE AND DEDICATED N.C. A&T is the nation’s No. 1 producer of minorities with degrees in science, mathematics, engineering and technology. Aggieland is the third largest producer of African-American engineers with master’s degrees and it is a leading producer of African-American engineers with doctorate degrees. Females comprise approximately 30 percent of the students in the College of Engineering, thus ranking the college sixth in the country in the percentage of degrees awarded to women. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

Teaching the March on Washington

Nearly a quarter-million people descended on the nation’s capital for the 1963 March on Washington. As the signs on the opposite page remind us, the march was not only for civil rights but also for jobs and freedom. Bottom left: Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the historic event, stands with marchers. Bottom right: A. Philip Randolph, the architect of the march, links arms with Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers and the most prominent white labor leader to endorse the march. Teaching the March on Washington O n August 28, 1963, the March on Washington captivated the nation’s attention. Nearly a quarter-million people—African Americans and whites, Christians and Jews, along with those of other races and creeds— gathered in the nation’s capital. They came from across the country to demand equal rights and civil rights, social justice and economic justice, and an end to exploitation and discrimination. After all, the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” was the march’s official name, though with the passage of time, “for Jobs and Freedom” has tended to fade. ; The march was the brainchild of longtime labor leader A. PhilipR andolph, and was organized by Bayard RINGER Rustin, a charismatic civil rights activist. Together, they orchestrated the largest nonviolent, mass protest T in American history. It was a day full of songs and speeches, the most famous of which Martin Luther King : AFP/S Jr. delivered in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. top 23, 23, GE Last month marked the 50th anniversary of the march. -

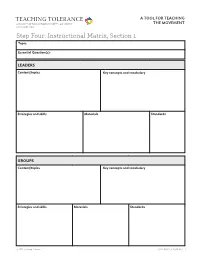

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Topic: Civil Rights History Grade level: Grades 4 – 6 Subject Area: Social Studies, ELA Time Required: 2 -3 class periods Goals/Rationale Bring history to life through reenacting a significant historical event. Raise awareness that the civil rights movement required the dedication of many leaders and organizations. Shed light on the power of words, both spoken and written, to inspire others and make progress toward social change. Essential Question How do leaders use written and spoken words to make change in their communities and government? Objectives Read, analyze and recite an excerpt from a speech delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Identify leaders of the Civil Rights Movement; use primary source material to gather information. Reenact the March on Washington to gain a deeper understanding of this historic demonstration. Connections to Curriculum Standards Common Core State Standards CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.1 Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.2 Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 5 topic or subject area. CCSS.ELA-Literacy SL.5.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. National History Standards for Historical Thinking Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources.