Nielsen Symphonies Nos 1–6 Sir Colin Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kleinbürgerin“ Und „Kleinbürger“ Im Drama Um Die Jahrhundertwende

„Kleinbürgerin“ und „Kleinbürger“ im Drama um die Jahrhundertwende. Studie zu den Dramen männlicher und weiblicher Autoren Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultäten der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität zu Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Shu-Mei Shieh aus Kaohsiung, Taiwan, R. O. C. Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Carl Pietzcker Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Irmgard Roebling Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses Des Gemeinsamen Ausschusses der Philosophischen Fakultäten I-IV: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Rebstock Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 21. Juni 2002 Danksagung Die Fertigstellung dieser Arbeit war ein langer Prozess. Auf diesem mühsamen Weg haben mich viele Menschen begleitet. Bedanken möchte ich mich bei Frau Professor Dr. Irmgard Roebling für ihre Anregung zu diesem Thema, für ihre Ratschläge und Begleitung. Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinem Doktorvater, Herrn Professor Dr. Carl Pietzcker, für seine wissenschaftliche Betreuung, seine Geduld und sein kritisches Interesse. Ohne seine fachliche und menschliche Unterstützung wäre die vorliegende Arbeit nie zustande gekommen. Wichtige Impulse gaben mir die anregenden Diskussionen im Graduiertenkolloquium mit Martina Groß, Youn Sin Kim, Kirstin Meier und Günter Thimm. Meinen Freundinnen Hsin Chou, Anna Kao, Hsin-Yi Lin, Eva Ottmer, Vera Schick, Dominique Schirmer und Su-Yun Yu möchte ich herzlich für ihre Ratschläge und ihr Engagement danken Abschließend möchte ich mich bei Chien-Tzung und meiner Familie sehr dafür be- danken, dass sie mir mit viel Fürsorge und -

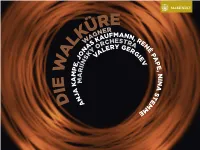

WAGNER / Рихард Вагнер DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (Conclusion) 1 Xii

lk a Waü GN r W , joNas k e e pe kY au r m iNs or f e ri C m i a a Val H k er e a m Y s N a t D j N G r N e , a r a r e G N i e é V p a p e , N i N a s t e e m m 2 Die Walküre Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (conclusion) 1 xii. Schwer wiegt mir der Waffen Wucht / My load of armour weighs heavy on me p18 2’28” DiE WAlkÜRE 2 xiii. Dritte Szene: Raste nun hier, gönne dir Ruh’! / Scene Three: Do stop here, and take a rest p18 8’56” (ThE VAlkyRiE / ВалькиРия) 3 xiv. Wo bist du, Siegmund? / Where are you, Siegmund? p19 3’49” 4 xv. Vierte Szene: Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! / Scene Four: Siegmund, look at me p19 10’55” Siegmund / Зигмунд...................................................................................................................................Jonas KAUFMANN / Йонас Кауфман 5 xvi. Du sahst der Walküre sehrenden Blick / you have seen the Valkyrie’s searing glance p20 4’27” hunding / Хундинг................................. ..............................................................................................Mikhail PETRENKO / михаил ПетренКо 6 xvii. So jung un schön erschimmerst du mir / So young and fair and dazzling you look p20 4’58” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René Pape / рене ПаПе 7 xviii. Funfte Szene: Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf / Scene Five: Deep as a spell sleep subdues p21 3’01” Sieglinde / Зиглинда........................................................................................................................................................Anja -

Durch Deutschland Und Die Welt Reisen

Wortschatz • Reisen • Eine Reise buchen • Unterbringungsmöglichkeiten • Transportmittel • Reiseziele • Auf einer Reise • Strandurlaub • Sehenswürdigkeiten und Aktivitäten • Wie war dein Urlaub? • Ausgewählte trennbare Verben • Ausgewählte untrennbare Verben • Über das Wetter sprechen • Aussprache • Kapitel 6: Auslautverhärtung and a helpful guide to recognizing German/English Cognates Grammatik Focus • Cases: Der Dativ • Irregular Verbs: gefallen • Irregular Verbs: geben • Conversational Past of separable prefix verbs • Conversational Past of DURCH DEUTSCHLAND inseparable prefix verbs Recommended • Verbs: Das Perfekt – UND DIE WELT REISEN Einführung Von der Reiseplanung bis hin zum Reisebericht geht in diesem Kapitel alles ums Reisen und um das Reisewetter! Verhexte (magical) Schlösser in Heidelberg, Kneipen in Amsterdam, verlassene (abandoned) Schönheiten, bizarre Mitbringsel, Reiseberichte, leckere Schokoladentorten, Inselstädte und mehr erwarten Sie! Videos Nach dem Einführungsvideo geht es an die Materialien. Sprache im Kontext 6 • Kerstens Flitterwochen 1. Arbeiten Sie mit den Interviews der deutschen Muttersprachler und den • Christines letzte Reise Interviews der Amerikaner. • Mario in Skandinavien 2. Erweitern Sie Ihren Wortschatz. • Josh reist nach Amsterdam 3. Lernen Sie mit den Videos „Sprache im Kontext“ Vokabeln und Ausdrücke im • Ein Wochenende in kulturellen Kontext kennen. Schottland 4. Wenden Sie grammatische Strukturen aus Grimm Grammar besser an. 5. Trainieren Sie Ihre Aussprache. 6. Vervollständigen Sie WebQuests. -

FINDET STADT Lage AUF SEITE 2

Ökumenisches Magazin der evangelischen und katholischen Weihnachten Kirche für Bielefeld | 2020 aktuelle FINDET STADT Lage AUF SEITE 2 Liebe Leserin, lieber Leser, fest zu wurde anschaulich: Gottes Dechant Norbert Nacke (M.), Gegenwart macht unser Leben hell! Weihnachten findet statt! Seit nahezu Superintendent Christian Bald (l.) Mit jedem Tag, den wir uns auf Gottes 2000 Jahren feiern Menschen dieses und Volker Gravemeier liebevolle Gegenwart besinnen, wach- Fest. Auch in diesem schon sehr be- sen auch in uns Liebe und Menschen- auf dem Alten Markt. sonderen Jahr wird es Weihnachten freundlichkeit. werden. Auch bei uns in Bielefeld wird Auf unseren Adventskränzen bren- gelten: Weihnachten findet Stadt! nen heute nicht mehr 24 Kerzen. Wir Doch wie findet uns das Fest mit sei- haben uns auf die vier Kerzen für die ner Botschaft in diesem Jahr vor? Sonntage beschränkt. So aber hat die- Vor einigen Tagen waren wir auf se sehr schöne Tradition sich bis in un- dem Weg zum Titelfoto des Weih- sere Wohnzimmer hinein ausbreiten nachtsmagazins. Doch irgendwie können. Sie bewahrt uns den Sinn für fremd war unser Weg durch die Bie- diese besondere Zeit und macht uns lefelder Fußgängerzone. Vereinzelte mit einer Botschaft vertraut, die ganz Buden standen hier und dort und nur nüchtern betrachtet, doch eigentlich wenige Menschen, alle jedoch mit fremd und wunderbar zugleich ist: „… maskierten Gesichtern, kamen uns ent- Gott wird Mensch dir, Mensch, zugute!“ gegen. Keine Spur vom traditionellen Irgendwie fremd und dann doch Weihnachtsmarkt neben der Nicolai- ganz richtig war das Ende unseres Kirche, kaum ein Hauch von gebrann- Fototermins. Wir waren noch kurz im ten Mandeln und nur das Glockenspiel Gespräch über dieses Magazin, als uns vom Kirchturm spielte adventliche zwei Mitarbeiter des Ordnungsamtes Klänge. -

Programmheft

- INHALT LIEBE EDITORIAL 3 VORWORTE 4 TIMETABLE 6 LIEBE LAGEPLAN 8 INFORMATIONEN 9 “DER HEILIGE AUGENBLICK IST DEINE EINLA ALVIN LUCIER 10 ANGELICA SUMMER 11 LIEBE BENEDIKT TER BRAAK 12 BRIAN PARKS 13 1 BRUEDER SELKE (CEEYS) 14 CARLOS CIPA 15 LIEBE CHORENSEMBLE FIAT ARS 16 CLEMENS CHRISTIAN POETZSCH 17 DAVID GRANSTRÖM 18 ELISA KÜHNL 19 LIEBE ENSEMBLE [___] 20 FRANCESCO CAVALIERE 21 GRAND RIVER 22 GREGOR SCHWELLENBACH 23 LIEBE HARTUNG & TRENZ 24 HAUSCHKA 25 JOHN KAMEEL FARAH 26 KONSTANTIN DUPELIUS 27 LUBOMYR MELNYK 30 LIEBE MARCOS MEZA 31 MARCUS SCHMICKLER 32 MARTA ZAPPAROLI 33 OZAN TEKIN 34 LIEBE PHILLIP SCHULZE 35 RESINA 36 ROGER ENO 37 SARAH DAVACHI 38 LIEBE SVEN HELBIG 39 THE EVER PRESENT ORCHESTRA 40 THE EVER PRESENT SAXOPHONES/ STRING QUARTETT 41 LIEBE TOBIAS THOMAS 42 VIOLA KLEIN 43 „DER HEILIGE AUGENBLICK IST DEINE EINLADUNG AN DIE LIEBE“ WALTRAUD BLISCHKE 44 AMELIE NEUMANN 45 LIEBE A CONTEMPLATION TOWARDS 46 GLOCKENBUCH [21/1000APOSTELN] 47 1 VORTRÄGE & WORKSHOPS 48 REDNER*INNEN 50 LIEBE DANK & SPONSOR*INNEN 53 IMPRESSUM 54 LIEBE AN DIE LIEBE“ 3 LIEBE EDITORIAL In diesem Jahr feiert unser Ambient-Festival über vier Tage verteilt 1000 Jahre St. Aposteln. Für dieses „Once-in-a-lifetime“-Ereignis haben wir ein Festprogramm LIEBE zusammengestellt, das liebevoller, umfänglicher und avancierter ist denn je: mit über 30 international renommierten Künstler*innen aus der zeitgenössisch elektronischen wie klassischen Musikszene, darunter der Chor FIAT ARS und Alvin Luciers THE EVER PRESENT ORCHESTRA, das unser diesjähriges LIEBE Festival-Orchester stellt. Unser Motto lautet ANNUM PER ANNUM, das heißt (lat.) „Jahr für Jahr“. Damit möchten wir Sie und unsere Künstler*innen inspirieren, Zeitlosigkeit zu reflek- tieren – in der Musik wie im Raum mit Konzerten, Performances und Installatio- LIEBE nen. -

Schiller Zeitreise Mp3, Flac, Wma

Schiller Zeitreise mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Zeitreise Country: Germany Released: 2016 Style: Ambient, Downtempo, Synth-pop, Trance MP3 version RAR size: 1417 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1682 mb WMA version RAR size: 1153 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 353 Other Formats: VQF XM MPC AIFF WAV DMF DTS Tracklist Hide Credits CD1-01 –Schiller Zeitreise I 2:18 CD1-02 –Schiller Schwerelos 6:20 CD1-03 –Schiller The Future III 5:40 Ile Aye CD1-04 –Schiller Mit Stephenie Coker 4:12 Vocals [Uncredited] – Stephenie Coker CD1-05 –Schiller Tiefblau 5:09 Der Tag...Du Bist Erwacht CD1-06 –Schiller Mit Jette von Roth 4:18 Vocals [Uncredited] – Jette von Roth CD1-07 –Schiller Somerregen 3:43 Playing With Madness CD1-08 –Schiller Mit Mia Bergström 5:01 Vocals [Uncredited] – Mia Bergström Leben...I Feel You CD1-09 –Schiller Mit Heppner* 3:51 Vocals [Uncredited] – Peter Heppner In Der Weite CD1-10 –Schiller 5:32 Vocals [Uncredited] – Anna Maria Mühe CD1-11 –Schiller Ultramarin 4:47 CD1-12 –Schiller Berlin - Moskau 4:33 CD1-13 –Schiller Salton Sea 4:49 CD1-14 –Schiller Mitternacht 4:28 CD1-15 –Schiller Polastern 4:29 Once Upon A Time CD1-16 –Schiller Backing Vocals [Uncredited] – Carmel Echols, 3:49 Chaz Mason, Samantha Nelson Dream Of You CD1-17 –Schiller Mit Heppner* 3:57 Vocals [Uncredited] – Peter Heppner Denn Wer Liebt CD1-18 –Schiller Mit Anna Maria Mühe 4:20 Vocals [Uncredited] – Anna Maria Mühe CD2-01 –Schiller Zeitreise II 4:01 Leidenschaft CD2-02 –Schiller Mit Jaki Liebezeit 4:50 Drums [Uncredited] – Jaki Liebezeit Morgentau -

Hat Als Blubo Sich Verdachtig Gemacht, Langst Ehe Die Abkurzung Uber Das Abgekurzte Die Wahrheit Sagte

The VolksstUcke III. THE VOLKSSTtJCKE Das VolksstUck ( ••• ) hat als Blubo sich verdachtig gemacht, langst ehe die AbkUrzung Uber das AbgekUrzte die Wahrheit sagte. UnbekUmmert (.,,) gab die Gattung zu verstehen, kleinstadtisches, landliches Leben, die Reste des vorindustriellen Zustands, taugten mehr als die Stadt; der Dialekt sei warmer als die Hochsprache, die derben Fauste die rechte Antwort auf urbane Zivilisation, (Theodor Adorno) (1). The following examination of the Volksstilcke, hitherto the focal point of Horvath scholarship, has three main intentions, Firstly, the present state of knowledge about the Volksstilcke will be ascertained, Leading on from this, an attempt will be made to reconstruct the image of the VolksstUck that existed in the period Horvath was writing, Particular emphasis will be placed on the later development of the genre after 1850 as a rural VolksstUck. Horvath critics have all too frequently associated Horvath's VolksstUck with the tradition of the Viennese Popular Comedy of Raimund and Nestroy, It would seem more logical that his Volksstilck is in fact a reaction against a more contemporary development, still very much alive as a dramatic form. The second section will be devoted to an analysis of Die Bergbahn, Horvath's first VolksstUck, which has been neglected in favour of the four later works, For this reason the play will be analysed separately and examined in its context as a reaction against the conservative ideological component inherent in the rural VolksstUck by this time, Horvath himself described it later as a "skizzenhaften Versuch" (II,663) but it nevertheless reveals the seeds of the later mature VolksstUcke and carries out equally effectively the genre critique of the VolksstUck, The four works.Italienische Nacht, Geschichten aus dem Wiener Wald, Kasimir und Karoline and Glaube Liebe Hoffnung will~understood as formally and thematically closely related works. -

November 2014, 04.12

LetschinerLetschiner RundschauRundschau GEMEINDE GEMEINDEGEMEINDE LETSCHIN 9. Jahrgang Letschin, den 02.05.2014 05-2014 9. Jahrgang9. JAHRGANG Letschin,LETSCHIN, den 01.09.2014DEN 30.10.2014 09-201411-2014 Ortsteile Gieshof-Zelliner Loose, Groß Neuendorf, Kiehnwerder, Kienitz, Letschin, Neubarnim, Ortwig, Sietzing, Sophienthal und Steintoch Seite 2 / 30.10.2014 Informatives Letschiner Rundschau / 9. Jahrgang Kommunalpolitischer Erfahrungsaustausch in der Partnergemeinde Pszczew vom 19.-20.09.2014 Nach einer Fahrt von ca. zwei Stun- sollte, begann mit einer kleinen boten ihr Können. Es gab auch den sind wir mit 17 Teilnehmern Panne, denn in unserem VW-Bus Gespräche mit den Einwohnern. am Ziel angekommen. Hier wur- war zu wenig Öl. Der Bürger- Um 15 Uhr brachte uns der Bür- den wir sehr freundlich begrüßt meister von Pszczew Waldemar germeister zu einer Gaststätte, es und zu unseren Unterkünften ge- Górczyński half aber sehr schnell gab ein Abschiedsessen und es ging bracht. Diese befanden sich in ei- und unkompliziert. Im Einwei- nach Letschin zurück. ner Urlaubsanlage in der Gemeinde hungsgebäude wurde uns und den Die Ferieneinrichtungen in der Pszczew mit dem Namen „JEZI- anwesenden Einwohnern in einem Gemeinde kann ich mit guten ORAK“, wo die Zimmer hell und polnisch-deutschen Vortrag darge- Gewissen weiterempfehlen. Es freundlich eingerichtet sind. Nach stellt, was die Gemeinde geschafft hat sich nicht nur die Gemeinde dem Empfang der Zimmerschlüs- hat und wie sie es erreicht hat. Das Pszczew entwickelt sondern auch sel fuhren wir mit einem Schulbus folgende Kulturprogramm hat mich das Straßennetz. durch die Gemeinde. Wenn ich sehr an Zuhause erinnert, Kin- mich nicht verzählt habe, waren dergartenprogramm, Musikgrup- Harald Karaschewski es neun Ortsteile, die wir besucht pen und eine Kapelle aus dem Ort Mitglied Ortsbeirat Groß Neuendorf haben. -

![Stadtbroschüre Weiden [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6908/stadtbrosch%C3%BCre-weiden-pdf-2186908.webp)

Stadtbroschüre Weiden [PDF]

Weiden Eine Stadt zum Verlieben Tourismus und Freizeit Eine Stadt zum Verlieben i Info Siehe Naherholung u. Oberpfälzer Wald ab Seite 32 Impressum: Lage Herausgeber des Magazins Stadt Weiden in der Oberpfalz Tourist-Information Oberer Markt 1 Die kreisfreie bayerische Stadt Weiden liegt mitten in 92637 Weiden der Oberpfalz. Etwa 100 km östlich von Nürnberg und Verantwortlich im Sinne ca. 25 km westlich von Tschechien, ist sie umgeben des Presserechts vom satten Grün des Oberpfälzer Waldes. Mit vielen Stadt Weiden in der Oberpfalz Attraktionen, Erholungsoasen und pulsierendem Leben Redaktionelle Mitarbeit heißt Weiden ihre Bewohner und Touristen herzlich Stadt Weiden in der Oberpfalz Tourist-Information willkommen. Agentur KREATIVMALEINS Florian Schläger, Silvia Kaiser-Schläger Waldsassen Recht Alle Rechte beim Herausgeber. Alle Rechte Vorbehalten. Nachdruck, Aufnahme in Onlinedienste sowie Internet und Vervielfältigungen auf Daten- Tirschenreuth träger wie z.B. CD-ROM, USB Sticks etc. nur nach Erbendorf vorheriger schritlicher Zustimmung des Herausgebers Falkenberg und Urhebers. Trotz sorgfältiger Auswahl der Quellen kann für die Windischeschenbach Richtigkeit nicht gehaftet werden. Insbesondere für Speinshart die in den Texten enthaltenen Informationen seitens Pressath Neustadt a.d. Waldnaab Tschechische der Interviewten. Republik Flossenbürg Grafenwöhr Bildnachweis Tourist-Information Stadt Weiden i.d.OPf., Touris- Weiden i.d.OPf. muszentren Oberpfälzer Wald, Max-Reger-Halle Weiden, Bauscher, Seltmann, Witt Weiden, Softintell, Mantel Pleystein Freizeitzentrum Weiden, Claudia Köppel, Kneipp- Vohenstrauß Verein Weiden, Alois Schröpf, Helmut Schieder, Gertrud Wittmann, Otto Vorsatz, Philipp Koller Leuchtenberg Eslarn Stand Juli 2019 Wernberg- Gesamtauflage: 10.000 Stück Köblitz Für diese Veröffentlichung wurden Daten aus verschiedenen Quellen herangezogen. Der Amberg Nabburg Nürnberg Herausgeber übernimmt keine Garantie oder Haftung für die Vollständigkeit, Aktualität oder Richtigkeit der bereitgestellten Informationen. -

Die Zauberflöte Premiere 30 September 1791, Vienna (Freihaustheater Auf Der Wieden) Seite Synopsis

Die Zauberflöte Premiere 30 September 1791, Vienna (Freihaustheater auf der Wieden) Seite Synopsis:......................................................................................................2 ERSTER AKT ........................................................................................................................................ 2 ZWEITER AKT....................................................................................................................................... 2 Libretto: .......................................................................................................3 OUVERTÜRE......................................................................................................................................... 3 ERSTER AKT......................................................................................................................................... 3 ERSTER AUFTRITT ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 ZWEITER AUFTRITT............................................................................................................................................................... 5 DRITTER AUFTRITT ............................................................................................................................................................... 8 VIERTER AUFTRITT ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Hans Pleschinski Am Götterbaum

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Hans Pleschinski Am Götterbaum 2021. 280 S., mit 2 Abbildungen ISBN 978-3-406-76631-2 Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier: https://www.chbeck.de/31824636 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München Diese Leseprobe ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Sie können gerne darauf verlinken. Hans Pleschinski Am Götterbaum Roman C.H.Beck © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München 2021 www.chbeck.de Zur Textgestaltung: Passagen, in denen Paul Heyse aus dem eigenen Werk zitiert, sind nicht kursiv hervorgehoben. Umschlaggestaltung: Kunst oder Reklame, München Umschlagabbildung: Münchner Innenstadt mit der Frauenkirche, iStock/Getty Images, © Melanie Maya Satz: Fotosatz Amann, Memmingen Druck und Bindung: Druckerei C.H.Beck, Nördlingen Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff) Printed in Germany ISBN 978 3 406 76631 2 klimaneutral produziert www.chbeck.de/nachhaltig Im Tor Der Wind frischte auf. Pappbecher rollten über das Pflaster. Das Gold der Mariensäule leuchtete im Abendschein. Aus den Passantenscharen blitzten Lichter der Smartphones. Chinesische und japanische Touristen konnte ein Einheimischer kaum unterscheiden. Gewiss waren auch Koreaner darunter. Selfie stangen drohten sich zu verhaken. Das neugotische Rathaus hielten offenbar viele Angereiste für mittelalterlich und knipsten den Trug bau von früh bis in die Nacht. Was erzählten sie in Shanghai oder in Sapporo zu ihren Schnappschüssen? Nein, das ist nicht Versailles, das war, glaube ich, in Kopenhagen. Aber welche Freunde und Ver wandten in Fernost wollten sich überhaupt Dutzende, Hunderte von abgelichteten Bauten Europas anschauen? Vielleicht nur die Groß mutter, bis sie auf der Reismatte einschliefe. Von vornherein Bildmüll. Zeitalter des Mülls. Überall, bis in die Bergwerksschächte und in die Tiefsee. -

WEBER Schreibt! Vorwort Weber Schreibt! Weber Schreibt! Vorwort

WEBER schreibt. Ein Projekt von Stipendiatinnen & Stipendiaten des Max Weber-Programms Bayern WEBER schreibt! Vorwort Weber schreibt! Weber schreibt! Vorwort Ob in Passau, München, Kempten oder Hof – die Stipendiatinnen und Stipendiaten des Max Weber-Programms studieren an unter- schiedlichen Hochschulen im Freistaat Bayern, und gerne auch im Ausland. Auch die Fächervielfalt reicht von A wie Agrarwissenschaften bis Z wie Zahnheilkunde. So breit und vielfältig wie ihre Studienfächer sind auch die außerfachlichen Interessen und Aktivitäten unserer Ge- förderten – vom Sport bis zum Erlernen neuer Sprachen, von der Musik- kapelle bis zur Geflüchtetenhilfe. Was sie eint, sind ihre Begabung, ihr Engagement, ihre Begeisterungsfähigkeit sowie ihre Neugierde und Offenheit für Neues. Mit der vorliegenden Anthologie Weber schreibt! begibt sich auch das Max Weber-Programm wieder auf neues Terrain: Wir freuen uns sehr, unsere erste literarische Veröffentlichung vorstellen zu dürfen, die, passend zum Max Weber-Programm, die Perspektive Bayern in den Mittelpunkt rückt. Schreibend lassen unsere Stipendiatinnen und Stipendiaten ihren Blick nach innen, nach außen und zurück schwei- fen. In Form von Lyrik, Essays, Kurzgeschichten, Fotografien und Das Max Weber-Programm ist ein 2005 eingerichtetes Aquarellmalerei umkreisen und nähern sie sich so der Frage nach der Programm des Freistaates Bayern zur Förderung oder den eigenen Identität(en). begabter junger Studierender. Es ist Teil des Elitenetzwerks Bayern und wird von der Studienstiftung des Der Ursprung dieser Sammlung geht auf einen Stammtisch in München deutschen Volkes e.V. mit Sitz in Bonn durchgeführt. zurück, bei dem sich einige unserer Stipendiatinnen und Stipendiaten, Aktuell werden rund 1.700 Stipendiatinnen und die am kreativen Schreiben interessiert sind, seit ein paar Jahren treffen.