Battle of Redmarley 1644

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gloucestershire Economic Needs Assessment

GL5078P Gloucestershire ENA For and on behalf of Cheltenham Borough Council Cotswold District Council Forest of Dean District Council Gloucester City Council Stroud District Council Tewkesbury Borough Council Gloucestershire Economic Needs Assessment Prepared by Strategic Planning Research Unit DLP Planning Ltd August 2020 1 08.19.GL5078PS.Gloucestershire ENA Final GL5078P Gloucestershire ENA Prepared by: Checked by: Approved by: Date: July 2020 Office: Bristol & Sheffield Strategic Planning Research Unit V1 Velocity Building Broad Quay House (6th Floor) 4 Abbey Court Ground Floor Prince Street Fraser Road Tenter Street Bristol Priory Business Park Sheffield BS1 4DJ Bedford S1 4BY MK44 3WH Tel: 01142 289190 Tel: 01179 058850 Tel: 01234 832740 DLP Consulting Group disclaims any responsibility to the client and others in respect of matters outside the scope of this report. This report has been prepared with reasonable skill, care and diligence. This report is confidential to the client and DLP Planning Ltd accepts no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report or any part thereof is made known. Any such party relies upon the report at their own risk. 2 08.19.GL5078PS.Gloucestershire ENA Final GL5078P Gloucestershire ENA CONTENTS PAGE 0.0 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 6 1.0 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 19 a) National -

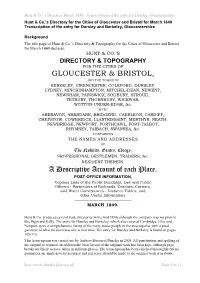

GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, a Descriptive Account of Each Place

Hunt & Co.’s Directory March 1849 - Transcription of the entry for Dursley, Gloucestershire Hunt & Co.’s Directory for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 Transcription of the entry for Dursley and Berkeley, Gloucestershire Background The title page of Hunt & Co.’s Directory & Topography for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 declares: HUNT & CO.'S DIRECTORY & TOPOGRAPHY FOR THE CITIES OF GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, AND THE TOWNS OF BERKELEY, CIRENCESTER, COLEFORD, DURSLEY, LYDNEY, MINCHINHAMPTON, MITCHEL-DEAN, NEWENT, NEWNHAM, PAINSWICK, SODBURY, STROUD, TETBURY, THORNBURY, WICKWAR, WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE, &c. W1TH ABERAVON, ABERDARE, BRIDGEND, CAERLEON, CARDIFF, CHEPSTOW, COWBRIDCE, LLANTRISSAINT, MERTHYR, NEATH, NEWBRIDGE, NEWPORT, PORTHCAWL, PORT-TALBOT, RHYMNEY, TAIBACH, SWANSEA, &c. CONTAINING THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF The Nobility, Gentry, Clergy, PROFESSIONAL GENTLEMEN, TRADERS, &c. RESlDENT THEREIN. A Descriptive Account of each Place, POST-OFFICE INFORMATION, Copious Lists of the Public Buildings, Law and Public Officers - Particulars of Railroads, Coaches, Carriers, and Water Conveyances - Distance Tables, and other Useful Information. __________________________________________ MARCH 1849. ___________________________________________ Hunt & Co. produced several trade directories in the mid 1850s although the company was not prolific like Pigot and Kelly. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley, which also covered Cambridge, Uley and Newport, gave a comprehensive listing of the many trades people in the area together with a good gazetteer of what the town was like at that time. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley is found on pages 105-116. This transcription was carried out by Andrew Barton of Dursley in 2005. All punctuation and spelling of the original is retained. In addition the basic layout of the original work has been kept, although page breaks are likely to have fallen in different places. -

GLOUCESTERSHIRE January 2014 GLOUCESTERSHIRE

GLOUCESTERSHIRE January 2014 GLOUCESTERSHIRE 1. SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY SERVICE(s) Gloucestershire Care 0300 421 8937 www.glos-care.nhs.uk/our-services/childrens-specific-services/childrens-speech-and-language-therapy-service The Independent Living Centre, Village Road, Services NHS Trust Cheltenham, Gloucestershire GL51 0BY 2. GOUCHESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL 01452 425000 www.gloucestershire.gov.uk Shire Hall, Westgate Street, Gloucester GL1 2TG [email protected] • SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS SEN Support Team www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/sen Shire Hall, Westgate Street, Gloucester GL1 2TP [email protected] The Communication and Interaction Team C&I Team www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/schoolsnet/article/114037/Communication-and-Interaction-Team (Advisory Teaching Service) Cheltenham 01242 525456 [email protected] Forest of Dean 01594 823102 [email protected] Gloucester 01452 426955 [email protected] Stroud 01453 872430 [email protected] • EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY The Educational Psychology Service www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/article/108322/Educational-Psychology Principal Educational Psychologist: Dr Deborah Shepherd 01452 425455 Cheltenham 01452 328160 Cotswolds 01452 328101 Forest of Dean 01452 328048 Gloucester 01452 328004 Stroud 01452 328131 3. SCHOOLS with specialist Speech and Language provision The following primary schools have Communication & Interaction Centres: Christ Church C of E Primary School 01242 523392 www.christchurchschool-chelt.co.uk -

Tewkesbury Borough Council Guide 2015 Tewkesbury.Gov.Uk

and Tewkesbury Borough Council Guide 2015 tewkesbury.gov.uk A ffreeree ccomprehensiveomprehensive gguideuide ttoo comcommunitymunity ssportsports cclubs,lubs, physical activity classes and other sport and leisure services in Tewkesbury Borough. www.tewkesbury.gov.uk • www.facebook.com/tewkesburyboroughsports For Mo re in forma on Pl ease contact th e sports centre 0168 4 29395 3 spo rts ce ntre@tewk esbu rys chool .or g Facili es av ailable fo r hi re - 4 Court Sports Hall - Badminton Courts - 20 m Swi mming Poo l - Fully equipped Fitness Studio - Me e ng rooms - Dance Studio - Gymnasium Bi rthday Par es - 1 hou r of - Drama Hall ac on packed spo r ng fun from - Tennis Courts football, bas ke tball, dodgeball, - Expressive arts rooms swimming or use of the sports - All Weather Pitch ce ntres own Bouncy Castle . - Large Fi eld Are a Pr ices from £24 per hour Onl y £26 per ho ur to pl ay on the All Wea ther Pit ch Swimming Lessons ar e fo r swimmers age d 4 yrs+ Classes ar e limited in size to enhance quality MONDAY AND THURSDAY NI GHT FOOTBALL LEAGUES Fully affiliated to the FA, qualifi ed referee s PRIZES fo r Di visio n Champions 0168 4 293953 sportsc entre@tewkesbur yschool.o rg 2 Sport and Physical Activity Guide Tewkesbu ry Borough 2015 Welcome to Tewkesbury Borough Council’s Sport and Physical Activity Guide for 2015. There are 10,000 copies of this free brochure distributed to schools, libr ar ie s, community centres, businesses and private homes in January each ye ar . -

Pathology Van Route Information

Cotswold Early Location Location Depart Comments Start CGH 1000 Depart 1030 Depart 1040 if not (1005) going to Witney Windrush Health Centre Witney 1100 Lechlade Surgery 1125 Hilary Cottage Surgery, Fairford 1137 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1205 Moore Health Centre BOW 1218 George Moore Clinic BOW 1223 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1237 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1247 White House Surgery MIM 1252 Mann Cottage MIM 1255 Chipping Campden Surgery 1315 Barn Close MP Broadway 1330 Arrive CGH 1405 Finish 1415 Cotswold Late Location Location Depart Comments Start Time 1345 Depart CGH 1400 Abbey Medical Practice Evesham 1440 Merstow Green 1445 Riverside Surgery 1455 CGH 1530-1540 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1620 Moore Health Centre BOW 1635 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1655 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1705 White House Surgery M-in-M 1710 Mann Cottage MIM 1715 Chipping Campden Surgery 1735 Barn Close MP Broadway 1750 Winchcombe MP 1805 Cleeve Hill Nursing Home Winchcombe 1815 Arrive CGH 1830 Finish 1845 CONTROLLED DOCUMENT PHOTOCOPYING PROHIBITED Visor Route Information- GS DR 2016 Version: 3.30 Issued: 20th February 2019 Cirencester Early Location Location Depart Comments Start 1015 CGH – Pathology Reception 1030 Cirencester Hospital 1100-1115 Collect post & sort for GPs Tetbury Hospital 1145 Tetbury Surgery (Romney House) 1155 Cirencester Hospital 1220 Phoenix Surgery 1230 1,The Avenue, Cirencester 1240 1,St Peter's Rd., Cirencester 1250 The Park Surgery 1300 Rendcomb Surgery 1315 Sixways Surgery 1335 Arrive CGH 1345 Finish 1400 Cirencester Late Location -

Gloucestershire. [Kelly's

432 BOO GLOUCESTERSHIRE. [KELLY'S BOOT & SHOE MAKER8-Continued. BOTTLE MANUFACTURERS- Carpenter & Co. Cainscross brewery, Trinder Alfred Harris, Campden S.O GLASS. Cainscross, Stroud TrinderW. Wit~ingtn.Andovrsfrd.R~. 0 Kilner Brothers, Great Northern Railway Cheltenha.m Orig~nal Brewery ~o. ~im. TruebodyW.Brldge Yate,Warmly.B1'lstl goods station KiuO"s cross London N (Arthur In. Shmner, managlllg dlrec- Tucker Alfred, Cinderford, Newnham 'b' tor; C. O. Webb, sec.), 160 High Turner E. & Co.Lim.7 Dyerst.Cirencstr BOTTLE BOX & CASE MKRS. street, Cheltenham Turner Ralph, 4 Gordon terrace, Sher- Kilner Brothers,Great Northern Railway Cirencester Brewery Lim. (T. Matthews, borne place, Cheltenham goods station, King's cross, London N sec.), Cricklade street, Cirencester Tyler George, 23 Middle street, Stroud Combe Benjamin, Grafton brewery, Tyler John, 161 Cricklade st.Cirencester BOTTLERS. Grafton road, Cheltenham Tyler William Henry,3 Nelson st.Strond See Ale & Porter Merchants & Agents. Combe GeorgeThomas, Brockhampton, Underhill Henry, Cinderford, Newnham Andoversford RS.O Underwood lsaac, Avening, Stroud BRASS FINISHERS. Cook ReginaldH. &Nathaniel &WaIter, Vick James, Barbican road, Gloucester Haines T. 2 Clare st. Bath I'd. Cheltnhm Hampton street, Tetbury Viner James, 2 Painswick parade, Thornton F. Oxford passage, Cheltnhm Coombe Valley Brewery, Coombe, Painswick road, Cheltenham Wynn E. 51 St. George's pI. Cheltenhm Wotton-under-Edge Virgo Joseph, Micheldean RS.O Wynn G. H. St. James' sq. Cheltenham Cordwell & Bigg, HamweIl Leaze Ward Mrs.A.Welford, Stratford-on-Avn brewery, Cainscross, Stroud Watkins :Fredk. Gloucester I'd. Coleford BRASS FOUNDERS. Davis Joseph, Portcullis hotel, Great ',:atkins J. Pi~lowell, Y?rkley, Lydney Gloucester Brass foundry (John Higgins, Badminton S.O . -

Gloucestershire

248 NEWENT. GLOUCESTERSHIRE. [KELLY'S son, escaping to one of the secret chambers in the house, Petty Sessions are held at the Sessions House every saved his life, and the place where he was concealed is alternate thursday, at 11.30 a.m. The following places 6till known as "Horton's Hole." Newent Court, the seat are included in the Petty Sessional Division :-Broms of Andrew Knowles esq. J.P. is a handsome residence, berrow, Corse, Dymock, Highleadon, Huntley, Kemp with colonnaded portico, standing on an eminence near ley, Newent, Oxenhall, Pauntley, Preston, Taynton, the church, in park-like grounds, finely timbered and Tibberton, Upleadon containing a beautiful lake. Stardens, the residence of F. A. Wilson esq. is 8 'finely built modern mansion of NEWENT RURAL DISTRICT OOUNCIL. stone, 8lianding in park-like grounds, about a. quarter of Meets at the Union every alternate thursday, no fixed a mile north. The Parks is the residence of Arthur time. William Montgomery-Campbell esq. Il.A. In 1558 one Clerk, Charles Tunnieliff, Culvert street Edward Horne was burnt at Old Court, formerly an Treasurer, Charles Nash, Capital &; Counties Bank, orchard connected with the Court House, for his religion: Broad street at Cugley, a. mile out of the town, there is a cavern in Medical Officer of Health, William Norris Marshall which Home is said to have concealed himself before his M.R.C.S.Eng. Church street capture. During the Civil war there was a garrison for Sanitary Inspector, Thomas Smith, Holts villa. the king at Newent, under the command of Colonel Meine, who was killed at Redmarley and buried at Gloucester. -

Land Off Bradfords Lane Newent Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation

Land off Bradfords Lane Newent Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation for WYG Environment on behalf of Kodiak Ltd CA Project: 6560 CA Report: 18168 March 2018 Land off Bradfords Lane Newent Gloucestershire Archaeological Evaluation CA Project: 6560 CA Report: 18168 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved by revision A 20/03/2018 D Sausins C Bateman C Bateman This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Land off Bradfords Lane, Newent, Gloucestershire: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................2 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................3 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND................................................................3 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES...................................................................................5 4. METHODOLOGY...............................................................................................5 5. RESULTS (FIGS 2-4).........................................................................................6 6. THE FINDS ........................................................................................................6 -

NOTES and QUERIES 105 35 Chipping Sodbury

NOTES AND QUERIES 105 Secondly, this is ultimately a depressingly materialistic book. If our faith is to be defined by our abstinence, as this book would appear to argue, then it is a secular not a spiritual pursuit. This book reflects the spirit of current Quaker dilemmas. Some argue our task is to rediscover our faith. Others our action. But we live in our present and can only change our future. Maybe we need to discover that. Then we can live in faith, which is action in itself. Richard Murphy NOTES AND QUERIES Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Gloucestershire Record Series, Volume 13 Bishop Season's Survey of the Diocese of Gloucester 1735-1750 Edited by John Fendley.2000, pp.xx, 204 "The edited text presents the content of all the six manuscripts of Benson's survey that are known to have survived. Letters in bold-face indicate those manuscripts. A G.D.R. 2858(1), dating from 1735 B G.D.R. 285B(3), dating from 1735-8 C G.D.R. 397, dating from 1743 and later D G.D.R. 381A, dating from 1750 E Gloucester Cathedral Library MS.52, dating from 1751 F G.D.R. 393, dating from 1751. The edited text is based on D, and shows the significant variants in the other alternations made to them and to D/' • GLOUCESTERSHIRE MEETINGS 1735-50 This survey would have been from the reports of parish officers in response to questions from Thomas Benson (1689-1752) bishop of Gloucester from 1735. Friends' meetings seem to have been picked up in reports of the following parishes: p.26 Didmarton & Oldbury 32 Pucklechurch 35 Chipping Sodbury 49 Thornbury (and a school) 58 Horsley [this parish is about a mile south of Nailsworth] Minchinhampton 60 Painswick 67 Tetbury 106 NOTES AND QUERIES 90 Gloucester "A silent meeting" 94 Cheltenham 98 Tewkesbury 108 Stoke Orchard 113 Chipping Campden [I suppose Broad Campden, in Butler 1999] 142 Stow on the Wold 149 Cirencester There is a fair sprinkling of Friends in the other parishes' returns. -

Gloucestershire Folk Song

Glos.Broadsht.7_Layout 1 15/10/2010 14:35 Page 1 1 4 A R iver Avon A4104 A3 8 9 Randwick cheese rolling and Randwick Wap Dover’s Games and Scuttlebrook Wake, Chipping 2 A about!’ and they routed the 8 Chipping 4 A JANUARY 4 A 43 First Sunday and second Saturday in May Campden – Friday and Saturday after Spring Bank 1 4 Camden French in hand-to-hand 4 Blow well and bud well and bear well Randwick is one Holiday 5 0 fighting. For this feat the 1 8 God send you fare well A3 Gloucestershires were of the two places The ‘Cotswold Olimpicks’ or ‘Cotswold Games’ were A43 A 8 3 Every sprig and every spray in Gloucestershire instituted around 1612 by Robert Dover. They mixed 8 allowed to wear two hat or A bushel of apples to be that still practices traditional games such as backsword fighting and cap badges – the only 2 9 given away cheese-rolling. On shin-kicking with field sports and contests in music 4 10 MORETON- regiment to do so. The Back Dymock A 1 IN-MARSH On New Year’s day in the TEWKESBURY 4 Badge carries an image of the first Sunday in A n 3 Wo olstone 4 morning r 5 A the Sphinx and the word May cheeses are e 1 2 4 ev 4 4 M50 8 S ‘Egypt’. The Regiment is now From dawn on New Year’s Day, rolled three times r 3 Gotherington e A 5 A v i part of The Rifles. -

Post Reformation Catholic History in the Forest of Dean and West Gloucestershire

POST REFORMATION CATHOLIC HISTORY IN THE FOREST OF DEAN AND WEST GLOUCESTERSHIRE. Michael Bergin ( Gloucestershire Catholic History Society ) The area we are going to look at today is that part of Gloucestershire that lies between the rivers Severn and Wye. Up until 1541 it was in the Diocese of Hereford, and in that year it became part of the newly created Diocese of Gloucester. The north of the area is served by the present day Catholic parish of Newent and Blaisdon. The south of the area, the Forest of Dean, is served by the Catholic Churches in Cinderford, Coleford and Lydney. But in the whole area there are only two Parish Priests. In the north of the area there are 20 Anglican churches that are of pre-Reformation Catholic origin, and in the Forest area there 18 such churches. The latter are situated around the boundaries of the Forest, outside of what was the Royal Demesne land. This land was kept as a hunting area for the monarch and any potential building development was prohibited, so that until legislation changed during the 19th century the area was extra- parochial. In May 1927, the then Bishop of Clifton, Ambrose Burton, received a letter from Mr George Hare of Cinderford. In his letter, Mr Hare pleaded the case for the sending of a priest to reside and Minister in the Forest area. Mr Hare had come to live in the Forest in 1919 and in the ensuing 8 years had not seen a Catholic priest there. He was concerned about the lack of Mass, of opportunity to receive the Sacraments, about the upbringing of his children and those of a small number of other families, in the Catholic faith. -

ILP, Cluster and Practice Programme Framework

Appendix 3 ILP, Cluster and Practice Programme Framework Library image 1 1 Overview A full breakdown of plans and supporting evidence is attached at appendix 6 an the follow Gloucestershire section provides a summary for each ILP ICS Cheltenham Cotswolds Forest of Dean Gloucester Stroud Tewkesbury ILP* ILP* ILP* ILP* ILP* ILP* PCN PCN PCN PCN PCN PCN North Aspen Berkeley Vale St Paul's Cotswolds Stroud Forest of Dean HQR TWNS Central South Cotswold Inner City Peripheral Cotswolds Severn Health North South Gloucester (NSG) * Integrated Locality Partnerships (ILPs) are Gloucestershire’s localised version of NHS England’s ‘Place’ level; The ILPs will help to deliver ICS, Health & Wellbeing and local priorities; ILPs will also support PCNs to deliver; Each ILP will collectively develop an ILP plan for their place. 1.1 Cheltenham ILP 3 1.2i Cheltenham summary • Population projections - 175,000 patients PCN Practices by 2031 Corinthian Surgery • New Cleevelands Medical Centre Portland Practice completed and open St Paul's Royal Well Surgery St Catherine's Surgery • Stoke Road refurbished and extended St George's Surgery • Winchombe extended Berkeley Place Surgery • Delivery of Prestbury Road Primary Care Crescent Bakery Surgery Centre due to be open end of 2020 Overton Park Surgery Central Royal Crescent Surgery • Delivery and procurement approach for a Underwood Surgery surgery at North West Elms housing Yorkleigh Surgery development Cleevelands Medical • Condition of remaining estate relatively Centre The Leckhampton Surgery acceptable but