Ncastellamento on the Po Plain: Cremona and Its Territory in the Tenth Century *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comune Di Corte De' Frati

COMUNE DI CORTE DE’ FRATI PROVINCIA DI CREMONA Deliberazione n° 28 Adunanza del 24/11/2014 VERBALE DI DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE Adunanza ordinaria di prima convocazione – seduta PUBBLICA OGGETTO: ACCORDO CONVENZIONALE PER L'ESERCIZIO ASSOCIATO DELLE FUNZIONI DI SEGRETARIO COMUNALE AI SENSI DELL'ART. 30 DEL D.LGS.267/2000 TRA I COMUNI DI CORTE DE' FRATI - OLMENETA - GRONTARDO - MALAGNINO E SCANDOLARA RIPA D'OGLIO L'anno duemilaquattordici, addì ventiquattro del mese di novembre alle ore 19:30, nella Sala Consiliare di via Cesare Battisti, 3, previa l’osservanza delle modalità e dei termini prescritti dalla Legge e dallo Statuto, sono stati convocati oggi a seduta i Consiglieri Comunali. All’appello risultano: . N. Cognome e Nome P A 1 AZZALI ROSOLINO SI 2 RUGGERI EMILIANO GIANNI SI 3 BRAGA SONIA SI 4 GAZZINA ALDO SI 5 CARLINO MASSIMO ARTURO SI 6 ROSSETTI GIUSEPPE SI 7 BUSANI LUCA SI 8 BEDANI ANDREA SI 9 BERTOLETTI LUIGI SI 10 BONAZZOLI PAOLO SI 11 CARLA' STEFANIA SI 12 GUINDANI LUIGI SI 13 ANSELMI EMANUELE SI Presenti 12 Assenti 1 Partecipa all’adunanza il Segretario Comunale Sig.ra Il Segretario Comunale Caporale Dott.ssa Mariateresa la quale provvede alla redazione del presente verbale. Accertata la validità dell’adunanza il Sig. Azzali Rosolino in qualità di SINDACO ne assume la presidenza, dichiarando aperta la seduta e invitando il Consiglio a deliberare in merito all’oggetto sopra indicato. 1 COMUNE DI CORTE DE’ FRATI PROVINCIA DI CREMONA OGGETTO: ACCORDO CONVENZIONALE PER L'ESERCIZIO ASSOCIATO DELLE FUNZIONI DI SEGRETARIO COMUNALE AI SENSI DELL'ART. 30 DEL D.LGS.267/2000 TRA I COMUNI DI CORTE DE' FRATI - OLMENETA - GRONTARDO - MALAGNINO E SCANDOLARA RIPA D'OGLIO IL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE PREMESSO che questo Comune, con propria deliberazione n. -

Filtea Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Tessili Abbigliamento

Archivio Storico Cgil Cremona fondo Filtea Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Tessili Abbigliamento 1961-2010 Inventario Serie: carteggio non classificato estremi cronologici Congresso 2° congresso - documenti provinciali e nazionali, relazione 1970 1971 4° congresso FILTEA, 9a congresso CGIL 1976 1977 verbali di assemblee congressuali 1977 2° congresso territoriale Filtea - verbali di assemblee, deleghe ecc. 1986 3° congresso territoriale Filtea - verbali di assemblee ecc. 1988 4° congresso regionale Filtea - Salice Terme, documenti, stampa, documenti del 1988 congresso nazionale Segreteria - miscellanea miscellanea CUZ 1970 1975 interventi e documenti direttivi unitari (provinciale, nazionale) 1971 s.d. elenchi e documenti CD nazionale 1971 1974 miscellanea CD provinciale FULTA 1974 1975 Comitato INCA 1974 1975 legge 405, legge reg. 44 - consultori 1976 1977 elenco e convocazione CD provinciale FILTEA 1977 richieste di incontro 1981 1987 miscellanea - comunicazioni a ditte, richieste assemblea, volantini, convocazioni 1982 1986 permessi sindacali 1983 1987 richieste assemblee 1984 1987 Amministrazione libri mastri 1967 bilanci 1967 1979 canalizzazione - misc. 1971 1981 miscellanea corrispondenza - amministrazione, canalizzazione 1978 1979 "copia lettere contributi regionali nazionali FILTEA e FULTA 1980 Bilancio Festa FULTA - Ostiano 1985 Organizzazione Conferenza di organizzazione; Cremona, 26.10.74 1974 1° convegno regionale FILTEA Lombardia 1976 Commissione femminile sindacale 1976 1979 sottoscrizione manifestazione di Roma, 26.5.78 -

Stato Delle Acque Superficiali Della Provincia Di Cremona

STATO DELLE ACQUE SUPERFICIALI DELLA PROVINCIA DI CREMONA RAPPORTO ANNUALE 2012 DIPARTIMENTO DI CREMONA Settembre, 2013 Stato delle acque superficiali della provincia di Cremona. Anno 2012 1 Il Rapporto annuale 2012 sullo stato delle acque superficiali è stato predisposto dall’Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente della Lombardia. Autori Dipartimento di Cremona ‐ U.O. Monitoraggi e Valutazioni Ambientali Alessandro Loda Elena Arnaud Le tematiche comuni a tutti i Dipartimenti sono state redatte da: Direzione Generale ‐ Settore Monitoraggi Ambientali ‐ U.O. Acque Nicoletta Dotti Pietro Genoni Massimo Paleari Laura Tremolada Direzione Generale ‐ Settore Monitoraggi Ambientali ‐ U.O. Risorse Naturali e biodiversità Rossella Azzoni PierFrancesca Rossi ARPA LOMBARDIA Dipartimento di Cremona Via Santa Maria in Betlem, 1 Direttore: Dott. Giampaolo Beati In copertina: Fiume Po, località Motta Baluffi (2012) ARPA Lombardia ‐ Dipartimento di Cremona Stato delle acque superficiali della provincia di Cremona. Anno 2012 2 Sommario 1 INTRODUZIONE ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2 IL QUADRO TERRITORIALE DI RIFERIMENTO ..................................................................................................... 4 3 IL QUADRO NORMATIVO DI RIFERIMENTO....................................................................................................... 7 3.1 OBIETTIVI DI QUALITÀ ............................................................................................................................................. -

Raccolte Differenziate 2019

CASALASCA SERVIZI SPA - RACCOLTE DIFFERENZIATE NEI COMUNI SOCI - ANNO 2019 (dati espressi in kg) Descrizione rifiuto altre imballaggi di imballaggi di imballaggi in imballaggi in imballaggi in imballaggi imballaggi assorbenti, pneumatici filtri dell`olio componenti gas in gas in rifiuti emulsioni carta e plastica legno materiali vetro e contenenti metallici materiali fuori uso rimossi da contenitori a contenitori a contenenti cartone misti lattine residui di contenenti filtranti apparecchia pressione pressione, olio provenienti sostanze matrici (inclusi filtri ture fuori (compresi gli diversi da da racc. diff. pericolose o solide dell`olio non uso, diversi halon), quelli di cui contaminati porose specificati da quelli di contenenti alla voce 16 da tali pericolose altrimenti), cui alla voce sostanze 05 04 sostanze (ad esempio stracci e 16 02 15 - pericolose codice CER 130802* 150101 150102 150103 150106 150106VETLAT150110* 150111* 150202* 160103 160107* 160216 160504* 160505 160708* COMUNE DI AZZANELLO 0 19.750 17.860 28.560 15 COMUNE DI BORDOLANO 14.780 16.620 19.640 32.640 12 COMUNE DI CALVATONE 76.920 43.030 43.600 66.840 COMUNE DI CASALBUTTANO ED UNITI 20 132.640 90.990 85.400 189.960 173 2.270 50 100 100 COMUNE DI CASALMAGGIORE 220 585.870 594.590 496.000 837.320 549 9.770 250 1.076 44 280 COMUNE DI CASTELDIDONE 0 18.340 3.840 26.770 COMUNE DI CASTELVERDE 173.030 154.640 155.120 291.700 230 2.580 85 250 COMUNE DI CICOGNOLO 12.790 28.120 43.140 75.480 30 COMUNE DI CINGIA DE` BOTTI 30.050 29.560 25.040 69.930 720 9 COMUNE DI CORTE DE` -

Comune Di Corte De' Frati

Piazza Roma 1 26010 Corte de’ Frati (CR) tel. 0372/93121 COMUNE DI CORTE DE’ FRATI fax 0372/93570 C.F. e P. IVA 00323930198 PROVINCIA DI CREMONA www.comune.cortedefrati.cr.it Email: [email protected] PEC: [email protected] PROCEDIMENTO DI VERIFICA DI ASSOGGETTABILITA’ A VAS DELLA PRIMA VARIANTE AL PGT VIGENTE DEL COMUNE DI CORTE DE’ FRATI CONFERENZA DI VERIFICA ai sensi dell’art. 4 della Legge Regionale n. 12/2005 e ss.mm.ii. VERBALE DELLA RIUNIONE DEL 6 MAGGIO 2015 Ai sensi e per gli effetti delle disposizioni contenute nella L.R. n. 12/2005 e ss.mm.ii. ed in attuazione degli “Indirizzi per la valutazione ambientale di piani e programmi” approvati dal Consiglio Regionale con deliberazione n.VIII/351 del 13/03/2007 e degli ulteriori adempimenti di disciplina approvati dalla Giunta Regionale con deliberazione n.VIII-6420/2007 e ss.mm.ii.; Richiamati: - la deliberazione della Giunta Comunale n.03 del 14/03/2014, con la quale è stata avviata la redazione della “Prima Variante al Piano di Governo del Territorio vigente” unitamente alla Verifica di assoggettabilità alla VAS; - il relativo avviso di avvio del procedimento pubblicato all’albo pretorio comunale on-line, sul sito informatico del Comune e sulla piattaforma regionale SIVAS; Ricordato che nella sopra citata deliberazione di Giunta Comunale n.03 del 14/03/2014 sono stati individuati: . l’autorità procedente: Responsabile Unico del Procedimento Arch. Luigi Agazzi; . l’autorità competente per la V.A.S.: Geom.Isa Sissa; . gli enti territorialmente interessati, -

GIUSEPPE AZZONI IL NOVERO DEI SOVVERSIVI Repertorio Dei

GIUSEPPE AZZONI IL NOVERO DEI SOVVERSIVI RepertorioRepertorio dei dei fascicoli fascicoli del del Casellario Casellario politico politico de lla dellaQuestura Questura di Cremonadi Cremona depositato depositato in’Archivio in Archivio di Statodi Stato Il novero dei sovversivi Se pure con fini ben diversi da quelli per i quali oggi li consultiamo e li studiamo, si sono prodotti, ordinati e conservati negli anni tanti documenti di storia e di memoria assai preziosi. Il casellario della Questura, al quale è complementare l’archivio della Prefettura – ambedue oggi presenti nel nostro Archivio di Stato – sono fonti ricchissime. Ne abbiamo tratto questo “repertorio” di tutti i fascicoli, con poche righe “distillate” dalle carte, anche numerose, relative ad ogni soggetto. Pare doveroso premettere alcune avvertenze, forse scontate ma non inutili. Fatti e giudizi riportati nelle sintesi riproducono sic et simpliciter , sia pure in estrema sintesi, quelli compilati dalla Questura, di ciò si tenga conto per una corretta comprensione ai nostri giorni. Quando leggiamo di un “sovversivo” antifascista che si iscrive al PNF e che si qualifica come “ravveduto” dobbiamo tenere ben presenti il come e il perché (cautele in merito sono qualche volta avanzate dagli stessi estensori). Quando leggiamo in un verbale di interrogatorio che un “clandestino” o un partigiano catturato rivela nomi e cose, i filtri per una odierna considerazione possono andare da una costrizione anche tremenda alla carota della contro- partita, dalla preoccupazione per i propri cari sotto minaccia a regole della clan- destinità che prevedevano cosa rivelare e cosa no... nulla va dato per scontato. La frequentissima presenza di “reati comuni” accanto a quelli politici non sempre ma quasi sempre si spiegano con condizioni di sopravvivenza che inducevano al furto di un ceppo (...l’albero degli zoccoli...), di legna, di foglie di gelso, di una gal- lina.. -

Istituti Comprensivi

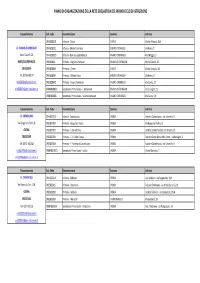

PIANO DI ORGANIZZAZIONE DELLA RETE SCOLASTICA DEL PRIMO CICLO DI ISTRUZIONE Tipo autonomia Cod. Sede Denominazione Comune Indirizzo CRAA82801B Infanzia - Chieve CHIEVE Via San Giorgio, 26/a I.C. BAGNOLO CREMASCO CRAA82802C Infanzia - Monte Cremasco MONTE CREMASCO Via Roma, 5 Vicolo Clavelli, 28 CRAA82803D Infanzia - Don Giuseppe Vanazzi VAIANO CREMASCO Via I Maggio, 2 BAGNOLO CREMASCO CREE82801L Primaria - Bagnolo Cremasco BAGNOLO CREMASCO Vicolo Clavelli, 28 CRIC82800E CREE82802N Primaria - Chieve CHIEVE Via San Giorgio, 28 Tel. 0373-648107 CREE82803P Primaria - Alfredo Gatti MONTE CREMASCO Via Roma, 17 [email protected] CREE82804Q Primaria - Vaiano Cremasco VAIANO CREMASCO Via Cavour, 27 [email protected] CRMM82801G Secondaria Primo Grado - L. Benvenuti BAGNOLO CREMASCO Via 2 Giugno, 19 CRMM82802L Secondaria Primo Grado - Vaiano Cremasco VAIANO CREMASCO Via Cavour, 26 Tipo autonomia Cod. Sede Denominazione Comune Indirizzo I.C. CREMA UNO CRAA82701G Infanzia - Castelnuovo CREMA Frazione Castelnuovo - via Valsecchi, 9 Via Borgo San Pietro, 8 CREE82701R Primaria - Borgo San Pietro CREMA Via Borgo San Pietro, 8 CREMA CREE82702T Primaria - S. Bernardino CREMA Località San Bernardino, Via Brescia, 23 CRIC82700P CREE82703V Primaria - C. A. Dalla Chiesa CREMA Frazione Santa Maria della Croce - via Battaglio, 5 Tel. 0373-256238 CREE82704X Primaria - F. Taverna di Castelnuovo CREMA Frazione Castelnuovo - via Valsecchi, 9 [email protected] CRMM82701Q Secondaria Primo Grado - Vailati CREMA Via del Ginnasio, 7 [email protected] Tipo autonomia Cod. Sede Denominazione Comune Indirizzo I.C. CREMA DUE CRAA82501X Infanzia - Sabbioni CREMA Loc. Sabbioni - via Cappuccini, 26/A Via Renzo da Ceri , 2/H CREE825015 Primaria - Benvenuti CREMA Frazione Ombriano - via Renzo Da Ceri, 2/H CREMA CREE825026 Primaria - Sabbioni CREMA Località Sabbioni - via Cappuccini, 26/A CRIC825003 CREE825037 Primaria - Morsenti CAPERGNANICA Via Garibaldi, 36 Tel. -

Comune Di Gadesco Pieve Delmona 1 a Cura Di Michele Cominetti

Pieve D desco elmo Ga na U n e picc un olo “grande” Com a cura di Michele Cominetti Comune di Gadesco Pieve Delmona 1 a cura di Michele Cominetti 2 Comune di Gadesco Pieve Delmona Gadesco Pieve Delmona Un piccolo “grande” Comune a cura di Michele Cominetti Comune di Gadesco Pieve Delmona In copertina: Acquerello di Doriana Grisi raffigurante il palazzo comunale Foto: Giada Delmiglio Layout: Michele Cominetti Stampa: Service Lito, Persico Dosimo (CR) ©2015 - Comune di Gadesco Pieve Delmona (CR) PREMESSAPREMESSA IlIl presentepresente opuscoloopuscolo haha lolo scoposcopo didi farfar conoscereconoscere llaa storiastoria ee lala realtàrealtà attualeattuale (cioè(cioè nelnel 2015)2015) deldel comunecomune didi GadescoGadesco PievePieve DelmonaDelmona situatosituato inin provinciaprovincia didi Cremona.Cremona. DopoDopo piùpiù didi trent’anni,trent’anni, aa frontefronte didi unun mutatomutato contecontestosto demografico,demografico, socialesociale eded economico,economico, l’Amministrazionel’Amministrazione ComunaleComunale ririproponepropone lala pubblicazionepubblicazione didi unun nuovonuovo opuscoloopuscolo riguardanteriguardante lala sstoria,toria, lala cultura,cultura, lele tradizionitradizioni deldel nostronostro paese,paese, auspicandoauspicando cheche quequestasta pubblicazionepubblicazione possapossa rappresentarerappresentare unun utileutile contributocontributo adad unauna miglmiglioreiore conoscenzaconoscenza deldel luogoluogo inin cuicui sisi vivevive .. RingraziamoRingraziamo tuttitutti colorocoloro cheche hannohanno collaboratocollaborato -

CONSULTAZIONE QUESITO ENTI LOCALI PD LOMBARDIA E TESSERAMENTO 2015 DOMENICA 1 MARZO - Provincia Di Cremona

CONSULTAZIONE QUESITO ENTI LOCALI PD LOMBARDIA e TESSERAMENTO 2015 DOMENICA 1 MARZO - Provincia di Cremona Comune sede di seggio Comuni accorpati Orario Seggio Indirizzo presidente seggio mail cellulare Cremona Gerre de Caprioli. Quartieri: Bagnara, Centro, Cascinetto, Giuseppina 09.00/12.00 - 14.30/18.00 Federazione PD via Ippocastani 2 Mariella Laudadio [email protected] 3488447478 Quartiere San Felice - San Savino 09.00/12.00 Centro Sociale San Felice via S.Felice 20 Eleonora Sessa [email protected] 3248727838 Quartieri: Borgo Loreto, Maristella,Magazzini Generali,San Bernardo,Zaist 09.00/12.00 Centro Sociale Pinoni (palazzo Duemiglia) via Brescia 94 Luigi Lipara [email protected] 3397478997 Quartiere Po 09.00/12.30 Gazebo viale Po - ang.via Oglio Carlo Duca [email protected] 3397785701 Quartieri:Boschetto,Cavatigozzi,Incrociatello,Itis,Migliaro,Picenengo,Sant'Ambrogio 09.00/12.00 Sede Circolo PD (c/o circolo Signorini) via Castelleone 7 Sergio Giazzi [email protected] 3290652241 Crema 09.00/12.00 - 14.30/18.00 Sede Coordinamento Cremasco via Bacchetta 2 Jacopo Bassi [email protected] 3290837735 Casalmaggiore 09.00/12.30 - 14.30 /17.00 Sede Circolo PD via Cavour 73 Edoardo Borghesi [email protected] 3479948493 Gussola Torricella del Pizzo 09.00/12.30 Sede Circolo PD piazza Comaschi Stefano Belli Franzini [email protected] 3281259304 Martignana 09.00/12.30 Saletta Comunale via Libertà Fabrizio Aroldi [email protected] 3460696493 Piadena Cà d'Andrea,Calvatone,Drizzona,Isola Dovarese,S.Giovanni in Croce, -

Padania Acque S.P.A. Presenta Il Piano Di Realizzazione Di Più Di 30 Nuove Case Dell’Acqua in Provincia Di Cremona

Padania Acque S.p.A. Via del Macello, 14 – 26100 Cremona Tel. 03724791 Fax. 0372479239 [email protected] www.padania-acque.it Padania Acque S.p.A. presenta il piano di realizzazione di più di 30 nuove case dell’acqua in provincia di Cremona Cremona, 29 marzo 2019 Padania Acque, di intesa con la Provincia di Cremona e l’ente d’Ambito ATO, ha presentato oggi pomeriggio, presso la sala del Consiglio del palazzo provinciale, il programma di realizzazione di più di trenta nuove case dell’acqua che si aggiungono alle trentasei già in funzione. Il Gestore unico dell’idrico cremonese ha avviato una gara pubblica per assegnare i lavori entro giugno in modo che nell’arco di un anno (estate 2020) più della metà dei Comuni del territorio provinciale potranno disporre di una casa dell’acqua cioè di un ulteriore punto di erogazione della stessa acqua di rete che arriva nelle case dei cittadini e che sgorga dai rubinetti e dalle fontanelle, ma disponibile anche refrigerata e frizzante. L’A.D. di Padania Acque, Alessandro Lanfranchi, ha commentato così l’importante intervento stanziato: «le case dell’acqua rappresentano un servizio pubblico molto apprezzato. Basti pensare che nel 2018 hanno distribuito 6 milioni 500 mila litri di acqua di cui, in media, circa il 60% naturale e il 40% gassata. Le prossime installazioni prevedono per la nostra società un rilevante investimento di circa un milione di euro. Un investimento in termini economici ma soprattutto in ottica di maggiore accessibilità all’acqua pubblica da parte dei cittadini. Un’azione che riguarderà l’intero territorio provinciale, incrementando significativamente la disponibilità della risorsa, secondo il principio fondamentale dell’”acqua per tutti”, tema della recente Giornata mondiale dell’acqua che abbiamo celebrato lo scorso 22 marzo». -

Curriculum Vitae Di Ivan Scaratti

CURRICULUM VITAE DI IVAN SCARATTI Il sottoscritto Ivan Scaratti, residente a Grontardo (CR) in via Garibaldi n. 26, C.F.: SCRVNI73S01D150I, consapevole delle sanzioni penali previste dall’art. 76 del D.P.R. 28 dicembre 2000, n. 445 per le ipotesi di falsità in atti e dichiarazioni mendaci, dichiara sotto la propria responsabilità, ai sensi dell’art. 46 e 47 dello stesso decreto 445/2000, il presente curriculum vitae: F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome IVAN SCARATTI Indirizzo VIA GARIBALDI N. 26, 26044 GRONTARDO (CR) Telefono 335/5346439 Fax E-mail [email protected] Nazionalità ITALIANA Data di nascita NATO A CREMONA IL 01/11/1973 ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date (da – a) DAL 16/12/2002 AD OGGI: DA I.P.A.B. OSPEDALE CIVILE OSTIANO AD A.S.P. BRUNO PARI OSTIANO • Nome e indirizzo del datore di FINO ALLA TRASFORMAZIONE IN A.S.P. (decreto della Direzione Generale Famiglia lavoro e Solidarietà Sociale della Giunta Regionale n. 16155 del 01.10.2003) I.P.A.B. OSPEDALE CIVILE OSTIANO Ho svolto le funzioni ed i compiti di SEGRETARIO DIRETTORE AMMINISTRATIVO (requisito previsto dal R.R. 11/2003) A.S.P. BRUNO PARI DI OSTIANO • Tipo di impiego DIRETTORE AMMINISTRATIVO (requisito previsto dal R.R. 11/2003) • Principali mansioni e -RESPONSABILE AMMINISTRATIVO DELL’AZIENDA E DEL SERVIZIO responsabilità AMMINISTRATIVO. SEGRETARIO DEL C.D.A.. RESPONSABILE AMMINISTRATIVO E GESTIONALE DEI SETTORI ECONOMATO E APPROVVIGIONAMENTI COMPRESO I SERVIZI LAVANDERIA, CUCINA, MANUTENZIONE, E SICUREZZA. RESPONSABILE DI PROCEDIMENTO PER GARE E ASTE PUBBLICHE. RESPONSABILE DI PROCEDIMENTO PROCEDURE PER LOCAZIONE IMMOBILI E ALIENAZIONI PATRIMONIALI. -

Proposta X Chiacchiere Teatro Itinerante

Cremona, 23 luglio 2015 Alla cortese attenzione Settore Politiche Sociali Comune di Cremona P.zza del Comune, 8 26100 Cremona Oggetto: Manifestazione CHIACCHIERE IN CORTILE 2015 - proposta di collaborazione La società Teatro Itinerante, in considerazione della proficua collaborazione attivatasi nell'ambito delle tre precedenti edizioni della manifestazione in oggetto sia con l'amministrazione comunale sia con la rete dei soggetti aderenti alla stessa, si rende disponibile a rinnovare tale collaborazione sulla base delle richieste pervenute in tal senso sia da parte delle realtà territoriali già convolte sia dall'Ente Pubblico titolare dell'iniziativa. Le modalità di tale collaborazione sono da intendersi in continuazione con le funzioni di progettazione, di programmazione, di cura della rete, di organizzazione già svolte dagli operatori di Teatro Itinerante in occasione di passate manifestazioni promosse e sostenute dall'Amministrazione in indirizzo. Si segnala che Teatro Itinerante esercita da tempo le mansioni sopra indicate in collaborazione con differenti realtà sia pubbliche sia private come: Istituti Scolastici di ogni ordine e grado, Pubbliche Amministrazioni, Associazionismo ed Enti del Terzo Settore. In relazione alla natura e alla modalità della collaborazione nell'ambito della manifestazione CHIACCHIERE IN CORTILE, si segnalano alcune significative esperienze che la società ha al suo attivo in ambito di: - promozione del libro e della lettura (iniziative di formazione per docenti e cittadinanza adulta, formazione studenti, incotri di promozione della lettura per bambini, adolescenti, adulti) • Provincia di Cremona – progetto ministeriale “Una valigia di libri che viaggia per te”; • Castello di Belgioioso (PV) - “Amico Libro”; • Bologna - “Fiera Internazionale del Libro per Ragazzi”; • Comune di Cremona - “Fantasticalibro”, “Officina del libro/Cremona racconta/libri sottobanco”, “Un dicembre di fiabe”; • Comune di Crema - “Librolandia”; • Ist.