Rio Favelas in Musical Comedy Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

Cinema Nacional E Ensino De Sociologia : Como Trechos De Filme E

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO CURITIBA 2016 ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Educação, no Curso de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Setor de Educação, Linha de Pesquisa Cultura, Escola e Ensino da Universidade Federal do Paraná-UFPR. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Dalla Costa CURITIBA 2016 Dedico este trabalho a todos os profissionais da educação que estiverem na praça Nossa Senhora de Salete (Curitiba) no dia 29 de abril de 2015. RESUMO Estudar o cinema na perspectiva da Sociologia passa, antes de tudo, por uma questão cultural, mas não se limita a isto. Pensar os desdobramentos que cercam a temática do cinema é, também, se deparar com questões de ordem social, política, econômica e ideológica das relações entre indivíduo e sociedade, levando-se em conta que as mesmas são estruturadas a partir das esferas da produção e do consumo. Este conjunto de relações constitui por si mesmo uma problemática das Ciências Sociais. Por isso, quando se trata da sala de aula, a projeção de um filme ou de um trecho de filme, não pode se restringir somente ao lazer ou ao entretenimento. Com a implantação da Lei n° 13.006 de junho de 2014, que torna obrigatória a exibição por 2 horas mensais de filmes nacionais nas escolas, a busca por maneiras de trabalhar o cinema nacional de forma significativa na sala de aula tornou-se premente.Foi a busca pela identificação de diferentes perspectivas de trabalho com cinema nacional no ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica que motivou esta pesquisa. -

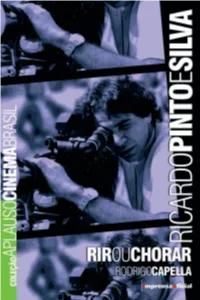

Ricardo Pinto E Silva

Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Ricardo miolo.indd 1 9/10/2007 17:34:34 Ricardo miolo.indd 2 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Rodrigo Capella São Paulo, 2007 Ricardo miolo.indd 3 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Governador José Serra Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Diretor Vice-presidente Paulo Moreira Leite Diretor Industrial Teiji Tomioka Diretor Financeiro Clodoaldo Pelissioni Diretora de Gestão Corporativa Lucia Maria Dal Medico Chefe de Gabinete Vera Lúcia Wey Coleção Aplauso Série Cinema Brasil Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho Coordenador Operacional e Pesquisa Iconográfica Marcelo Pestana Projeto Gráfico Carlos Cirne Editoração Aline Navarro Assistente Operacional Felipe Goulart Tratamento de Imagens José Carlos da Silva Revisão Amancio do Vale Dante Pascoal Corradini Sarvio Nogueira Holanda Ricardo miolo.indd 4 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Apresentação “O que lembro, tenho.” Guimarães Rosa A Coleção Aplauso, concebida pela Imprensa Oficial, tem como atributo principal reabilitar e resgatar a memória da cultura nacional, biogra- fando atores, atrizes e diretores que compõem a cena brasileira nas áreas do cinema, do teatro e da televisão. Essa importante historiografia cênica e audio- visual brasileiras vem sendo reconstituída de manei ra singular. O coordenador de nossa cole- ção, o crítico Rubens Ewald Filho, selecionou, criteriosamente, um conjunto de jornalistas especializados para rea lizar esse trabalho de apro ximação junto a nossos biografados. Em entre vistas e encontros sucessivos foi-se estrei- tan do o contato com todos. Preciosos arquivos de documentos e imagens foram aber tos e, na maioria dos casos, deu-se a conhecer o universo que compõe seus cotidianos. -

Amácio Mazzaropi's Filmography

Amácio Mazzaropi’s Filmography Sai da Frente—Get Out of the Way São Paulo, 1952 Cast: Amácio Mazzaropi; Ludy Veloso Leila Parisi, Solange Rivera, Luiz Calderaro, Vicente Leporace, Luiz Linhares, Francisco Arisa, Xandó Batista, Bruno Barabani, Danilo de Oliveira, Renato Consorte, Príncipes da Melodia, Chico Sá, José Renato, o cão Duque (Coronel), Liana Duval, Joe Kantor, Milton Ribeiro, Jordano Martinelli, Izabel Santos, Maria Augusta Costa Leite, Carlo Guglielmi, Labiby Madi, Jaime Pernambuco, Gallileu Garcia, José Renato Pécora, Toni Rabatoni, Ayres Campos, Dalmo de Melo Bordezan, José Scatena, Vittorio Gobbis, Carmen Muller, Rosa Parisi, Annie Berrier, Ovídio ad Martins Melo—acrobats 80 minutes/black and white. Written by Abílio Pereira de Almeida and Tom Payne. Directed by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. Produced by Pio Piccinini/Companhia Cinematográfica Vera Cruz. Opening: 06/25/1952, Cine Marabá and 12 movie theaters. Awards: Prêmio Saci (1952) best supporting actress: Ludy Veloso. Nadando em dinheiro—Swimming in Money São Paulo, 1952 Cast: Amácio Mazzaropi; Ludy Veloso, A. C. Carvalho, Nieta Junqueira, Liana Duval, Carmen Muller, Simone de Moura, Vicente Leporace, Xandó Batista, Francisco Arisa, Jaime Pernambuco, Elísio de Albuquerque, Ayres Campos, Napoleão Sucupira, Domingos Pinho, Nélson Camargo, Bruno Barabani, Jordano Martinelli, o cão Duque (Coronel), Wanda Hamel, Joaquim Mosca, Albino Cordeiro, Labiby Madi, Maria Augusta Costa Leite, Pia Gavassi, Izabel Santos, Carlos Thiré, Annie Berrier, Oscar Rodrigues 152 ● Amácio Mazzaropi’s Filmography de Campos, Edson Borges, Vera Sampaio, Luciano Centofant, Maury F. Viveiros, Antônio Augusto Costa Leite, Francisco Tamura. 90 minutes/ black and white. Written by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. Directed by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. -

Embodying Citizenship in Brazilian Women's Film, Video, And

Embodying Citizenship in Brazilian Women’s Film, Video, and Literature, 1971 to 1988 by Leslie Louise Marsh A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Romance Languages and Literatures: Spanish) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Catherine L. Benamou, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Lawrence M. La Fountain-Stokes, Co-Chair Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield Associate Professor Maria E. Cotera Assistant Professor Paulina Laura Alberto A catfish laughs. It thinks of other catfishes In other ponds. ⎯ Koi Nagata © Leslie Louise Marsh 2008 To my parents Linda and Larry Marsh, with love. To all those who helped and supported me in Brazil and To Catherine Benamou, whose patience is only one of her many virtues, my eternal gratitude. ii Table of Contents Dedication ii Abstract iv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 2 The Body and Citizenship in Clarice Lispector’s A 21 Via Crucis do Corpo (1974) and Sonia Coutinho’s Nascimento de uma Mulher (1971) 3 Comparative Perspectives on Brazilian Women’s 90 Filmmaking and the State during the 1970s and 1980s 4 Contesting the Boundaries of Belonging in the Early 156 Films of Ana Carolina Teixeira Soares and Tizuka Yamasaki 5 Reformulating Civitas in Brazil, 1980 to 1989 225 6 Technologies of Citizenship: Brazilian Women’s 254 Independent and Alternative Film and Video, 1983 to 1988 7 Conclusion 342 Sources Consulted 348 iii Abstract Embodying Citizenship in Brazilian Women’s Film, Video, and Literature, 1971 to 1988 by Leslie Louise Marsh Co-Chairs: Catherine L. Benamou and Lawrence M. -

O I Festival Internacional De Cinema Do Brasil (1954)

O I Festival Internacional de Cinema do Brasil (1954) Rafael Morato Zanatto Escola de Comunicaça o e Artes, Universidade de Sa o Paulo (ECA/ USP – FAPESP) [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6623-4668 RESUMO O I Festival Internacional de Cinema do Brasil (1954) foi a tentativa brasileira de participar do circuito internacional dos festivais de cinema que ganhou fo lego na Europa apo s a II Guerra Mundial. Concebido como parte das comemoraço es do IV Centena rio da cidade de Sa o Paulo, o festival baseou-se no modelo dos festivais de Cannes, Veneza, Bruxelas (1947) e Knokke Le Zoute (1949). Aprofundando as liço es dos festivais europeus, o brasileiro harmonizou em sua programaça o mostras de enfoque comercial e retrospectivas culturais, mas com o fracasso das expectativas comerciais locais e com o sucesso das programaço es culturais, cristalizou-se a percepça o em parcela da crí tica e da cro nica que arte e mercado foram dispostas em polos opostos, no qual as mostras comerciais haviam sido preteridas em relaça o a s retrospectivas e atividades de cunho cultural. Analisando historicamente o caso do festival, veremos como seu fracasso comercial e sua u nica realizaça o resultam diretamente da crise econo mica que se abateu sobre o paí s e sobre a indu stria cinematogra fica local, demonstrando que oposiça o entre arte e come rcio reflete, na realidade, disputas entre as cinematografias estadunidense e europeia. Veremos ainda que a vitalidade das programaço es culturais sera fundamental para a boa repercussa o que o evento alcançara na crí tica estrangeira, evitando o fracasso completo da iniciativa. -

Zully Rodriguez Wikipedia Diccionari

Zully rodriguez wikipedia diccionari Continue The cinema arrived in Latin America in 1896, a year after its first public screening in Paris. With him came film and projection equipment and specialists of the region, mainly Italian. In Argentina, in the early 20th century, the Frenchman Eugenio Pai made the first films, the Italian Atelio Lipizzi founded the film company Italate-Argentina, and the Austrian Max Gluxmann created a distribution system vital to the sound period. When the first exhibition halls appeared, another important pioneer, The Italian Mario Gallo, appeared, followed by his compatriots Edmundo Peruzzi and Federico Valle. Uruguayan Julio Raul Alsina, associated with distribution and exhibition, was the first to open a studio with a laboratory. Argentinian cinema has revealed other names, such as Edmo Cominetti, Nelo Kosimi, Jose Agustan Ferreira, Roberto Guidi, Julio Irigoyen and Leopoldo Torre Rios, who joined the board of directors of the silent period. The cinema was opened in Rio de Janeiro in the so-called beautiful era of Brazilian cinema, in the early 20th century, the Portuguese Antonio Leal, the Spanish Francisco Serrador, the Brazilian brothers Alberto and Paulino Bocheli and Marc Ferres and his son, Jalio (associated with Pate, from Paris) followed. German Eduardo Hirtz appeared in Porto Alegre. Around 1912, the regional features of silent cinema were laid out: in Pelotas, Portuguese Francisco Santos; in Belo Horizonte, Italians Igino Bonfioli; in Barbazen, Paulo Benedetti; in Sao Paulo, other Italians, Vittorio Capellaro, Gilberto Rossi and Arturo Carrari; in Campias, Felipe Ricci and E.K. Kerrigan of The United in Recife, Gentile Roise, Ari Sever, Jota Soares and Edson Chagas; in the Amazon region, two documentary filmmakers, The Portuguese Silvino Santos (Manaus) and the Spaniard Ramon de Banos (Belem). -

Crítica De Cinema Em O Tempo – 1953

CRÍTICA DE CINEMA EM O TEMPO – 1953 Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira Índice MESSALINA (“Messalina”) Itália Direção e Produção: Carmine Gallone. 8 CUIDADO COM AS LOURAS (André Hunbele)....................................... 10 ESCRAVO DE SI MESMO ......................................................................... 12 CASA-TE E VERÁS .................................................................................... 14 NOVA REVOLUÇÃO?................................................................................ 16 SCARAMOUCHE........................................................................................ 18 OS QUE NÃO DEVEM NASCER............................................................... 20 OS COVARDES NÃO VIVEM ................................................................... 22 SANHA SELVAGEM .................................................................................. 24 O ÍDOLO CAÍDO......................................................................................... 26 NOTICIÁRIO ............................................................................................... 28 SENHORA DE FATIMA............................................................................. 30 NOMENCLATURA EM CINEMA ............................................................. 32 O SEGREDO ................................................................................................ 34 CIDADE CATIVA ....................................................................................... 36 MISSÃO PERIGOSA EM TRIESTE.......................................................... -

Branding Latin America Film Festivals and the International Circulation of Latin American Films

Branding Latin America Film Festivals and the International Circulation of Latin American Films Laura Rodríguez Isaza Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Modern Languages and Cultures Centre for World Cinemas October, 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others . This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement . Except where otherwise noted, t his work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution -Non Commercial- Share Alike 2. 0 UK: England & Wales (CC BY -NC-SA 2.0). Full license conditions available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by -nc-sa/2.0/uk/ © 2012 The University of Leeds and Laura Rodríguez Isa za Acknowledgements I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement to go throughout the different stages of this research. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors at the Centre for World Cinemas of the University of Leeds without whose backing this research would not have been possible. I am especially indebted to Lúcia Nagib for her committed mentorship and encouragement to continue despite my frequent blockages. Her extensive knowledge and academic rigour enriched this research through a constant ex-change of ideas that helped me not only to express my arguments more clearly on paper but to develop further my thinking about the complexities of cinema as an object of study. -

Pg2.015 Vc Portuguese Films

UW-Madison Learning Support Services May 7, 2019 Van Hise Hall - Room 274 SET CALL NUMBER: PG2.015 VC PORTUGUESE FILMS ON VIDEO (Various distributors, 1986-89) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Portuguese culture and civilization: feature film DESCRIPTION: Popular & classic films either produced in the Portuguese language, or about a Portuguese or Brazilian subject. Most have English subtitles. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours to preview them or show them in class. AUDIENCE: Any; Portuguese is needed for films not subtitled FORMAT: VHS; NTSC CONTENTS CALL NUMBER 5x Favela agora por nos mesmos PG2.015.123 Brazil. 2010. DVD. Color. In Portuguese w/English subtitles. 99 min. Drama. Directed by Carlos Diegues, Renata de Almeida Magalhaes. O Aleijadinho : paixão, glória e suplío PG2.015.107 Brazil. 2000. DVD, requires region free player. In Portuguese w/English subtitles. Directed by Geraldo Santos Pereira. 100 min. An historian’s search for the daughter-in-law of Antonio Francisco Lisboa opens this dramatization of the life of the Brazilian sculptor and architect known as Aleijadihno. All Nudity Shall be Punished PG2.015.079 Almost Brothers PG2.015.106 Brazil. 2004. DVD. 102 min. Color. In Portuguese w/English subtitles. Directed by Lucia Murat. Look at the class struggle in Brazil over a period of four decades is told through the closely linked yet fatally divided lives of Miguel, a middle-class white rebel, and Jorge, his black childhood friend. Amores (Loves) PG2.015.058 Brazil. 1998. DVD. 95 min. Color. -

Cinema Comparat/Ive Cinema

CINEMA COMPARAT/IVE CINEMA VOLUME IV · No.9 · 2016 Editors: Gonzalo de Lucas (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) and Albert Elduque (University of Reading). Associate Editors: Núria Bou (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) and Xavier Pérez (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Advisory Board: Dudley Andrew (Yale University, United States), Jordi Balló (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain), Raymond Bellour (Université Sorbonne-Paris III, France), Francisco Javier Benavente (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Nicole Brenez (Université Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne, France), Maeve Connolly (Dun Laoghaire Institut of Art, Design and Technology, Irleland), Thomas Elsaesser (University of Amsterdam, Netherlands), Gino Frezza (Università de Salerno, Italy), Chris Fujiwara (Edinburgh International Film Festival, United Kingdom), Jane Gaines (Columbia University, United States), Haden Guest (Harvard University, United States), Tom Gunning (University of Chicago, United States), John MacKay (Yale University, United States), Adrian Martin (Monash University, Australia), Cezar Migliorin (Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil), Alejandro Montiel (Universitat de València), Meaghan Morris (University of Sidney, Australia and Lignan University, Hong Kong), Raffaelle Pinto (Universitat de Barcelona), Ivan Pintor (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Àngel Quintana (Universitat de Girona, Spain), Joan Ramon Resina (Stanford University, United States), Eduardo A.Russo (Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina), Glòria Salvadó (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Yuri Tsivian (University of Chicago, United States), -

12.0.812.888.Pdf

Anselmo Duarte capa.indd 1 18/6/2009 13:47:13 Anselmo Duarte O Homem da Palma de Ouro miolo Anselmo Duarte opçao 2.indd 1 17/6/2009 16:36:59 miolo Anselmo Duarte opçao 2.indd 2 17/6/2009 16:36:59 Anselmo Duarte O Homem da Palma de Ouro Luiz Carlos Merten miolo Anselmo Duarte opçao 2.indd 3 17/6/2009 16:36:59 Governador José Serra Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Coleção Aplauso Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho miolo Anselmo Duarte opçao 2.indd 4 17/6/2009 16:36:59 Apresentação Segundo o catalão Gaudí, Não se deve erguer monumentos aos artistas porque eles já o fize- ram com suas obras. De fato, muitos artistas são imortalizados e reverenciados diariamente por meio de suas obras eternas. Mas como reconhecer o trabalho de artistas ge niais de outrora, que para exercer seu ofício muniram-se simplesmente de suas próprias emo- ções, de seu próprio corpo? Como manter vivo o nome daqueles que se dedicaram a mais volátil das artes, escrevendo dirigindo e interpretando obras primas, que têm a efêmera duração de um ato? Mesmo artistas da TV pós-videoteipe seguem esquecidos, quando os registros de seu trabalho ou se perderam ou são muitas vezes inacessíveis ao grande público. A Coleção Aplauso, de iniciativa da Imprensa Oficial, pretende resgatar um pouco da memória de figuras do Teatro, TV e Cinema que tiveram participação na história recente do País, tanto dentro quanto fora de cena. Ao contar suas histórias pessoais, esses artistas dão-nos a conhecer o meio em que vivia toda uma classe que representa a consciência crítica da sociedade.