Zully Rodriguez Wikipedia Diccionari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

Filmkatalog IAI Stand Februar 2015 Alph.Indd

KATALOG DER FILMSAMMLUNG Erwerbungen 2006 - 2014 CATÁLOGO DE LA COLECCIÓN DE CINE Adquisiciones 2006 - 2014 Inhalt Argentinien............................................................................. 4 Bolivien....................................................................................18 Brasilien...................................................................................18 Chile.........................................................................................31 Costa Rica................................................................................36 Cuba.........................................................................................36 Ecuador....................................................................................43 Guatemala...............................................................................46 Haiti.........................................................................................46 Kolumbien...............................................................................47 Mexiko.....................................................................................50 Nicaragua.................................................................................61 Peru.........................................................................................61 Spanien....................................................................................62 Uruguay...................................................................................63 Venezuela................................................................................69 -

FAMECOS Mídia, Cultura E Tecnologia Metodologias

Revista FAMECOS mídia, cultura e tecnologia Metodologias A legião dos rejeitados: notas sobre exclusão e hegemonias no cinema brasileiro dos anos 20001 The legion of rejected: notes on exclusion and hegemonies in the years 2000 Brazilian cinema JOÃO GUILHERME BARONE REIS E SILVA Professor do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação Social (PPGCOM-PUCRS) – Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. <[email protected]> RESUMO ABSTRACT Este artigo retoma questões relacionadas ao desempenho dos This paper reworks on questions related with the performance filmes de longa metragem nacionais lançados no mercado of the Brazilian feature film released in the theatrical market, de salas, entre os anos 2000-2009, os quais não atingiram a in the years 2000-2009, whose box office did not reach the marca de 50 mil espectadores, propondo algumas reflexões mark of 50 thousand spectators, in order to propose some sobre a ocorrência de processos hegemônicos e de exclusão reflections about a process of hegemonies and exclusion que parecem ter se estabelecido no cinema brasileiro that seems to be settled in the contemporary Brazilian contemporâneo. cinema. Palavras-chaves: Cinema brasileiro; Distribuição; Indústria Keywords: Brazilian cinema; Distribuition; Film industry. cinematográfica. Porto Alegre, v. 20, n. 3, pp. 776-819, setembro/dezembro 2013 Baronea, J. G. – A legião dos rejeitados Metodologias a identificação de hegemonias e assimetrias DDurante o projeto de pesquisa Comunicação, tecnologia e mercado. Assimetrias, desempenho e crises no cinema brasileiro contemporâneo, iniciado em 2009, uma das principais constatações foi o estabelecimento de um cenário de assimetrias profundas entre os lançamentos nacionais que chegavam ao mercado de salas, no período compreendido entre os anos 2000-2009. -

Cinema Nacional E Ensino De Sociologia : Como Trechos De Filme E

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO CURITIBA 2016 ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Educação, no Curso de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Setor de Educação, Linha de Pesquisa Cultura, Escola e Ensino da Universidade Federal do Paraná-UFPR. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Dalla Costa CURITIBA 2016 Dedico este trabalho a todos os profissionais da educação que estiverem na praça Nossa Senhora de Salete (Curitiba) no dia 29 de abril de 2015. RESUMO Estudar o cinema na perspectiva da Sociologia passa, antes de tudo, por uma questão cultural, mas não se limita a isto. Pensar os desdobramentos que cercam a temática do cinema é, também, se deparar com questões de ordem social, política, econômica e ideológica das relações entre indivíduo e sociedade, levando-se em conta que as mesmas são estruturadas a partir das esferas da produção e do consumo. Este conjunto de relações constitui por si mesmo uma problemática das Ciências Sociais. Por isso, quando se trata da sala de aula, a projeção de um filme ou de um trecho de filme, não pode se restringir somente ao lazer ou ao entretenimento. Com a implantação da Lei n° 13.006 de junho de 2014, que torna obrigatória a exibição por 2 horas mensais de filmes nacionais nas escolas, a busca por maneiras de trabalhar o cinema nacional de forma significativa na sala de aula tornou-se premente.Foi a busca pela identificação de diferentes perspectivas de trabalho com cinema nacional no ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica que motivou esta pesquisa. -

ISA Library Feature Films

Institute for the Study of the Americas 17/12/2012 Title Year Format ISA Library Feature Films Abrazo partido, El (DVD) Daniel Burman 2004 Adventures of Juan Quin Quin (Cuban Masterworks Collection-DVD) Julio García Espinosa 1967 Aguirre, wrath of God Werner Herzog 1995 Albañiles, Los Jorge Fons 1976 Alias La Gringa Alberto Durant 1991 All the President’s men Pakula, Alan J. 2006 Alla lejos y hace tiempo Manuel Antin 1974 Aller simple Alsino y el Condor (2 copies available) Miguel Littin 1982 Amada (Cuban Masterworks Collection-DVD) Humberto Solás 1981 Amiga, La Jeanine Meerapfel 1988 Amnesia Gonzálo Justiniano 1994 Amores perros Alejandro González Iñarritu 2001 Amreeka Cherien Dabis 2009 Angel de fuego Dana Rotberg 1999 Antonio des Mortes 1994 Apocalypto Mel Gibson 2007 Argie Jorge Blanco 1983 Aunt Julia and the scriptwriter Jon Amiel Bandida, La Batimam e Robim Ivo Branco Before Night Falls Bella del Alhambra, La Enrique Pineda Barnet 1990 Betun y sangre / Man of one note 1994 Black God, white Devil Glauber Rocha 1964 Blood of the condor Jorge Sanjines 1969 *see note* **supposed to be 2 copies but only one found; but copy no.1918079339 is faulty ** Boca del lobo, La Francisco J Lombardi 1988 Boda secreta Alejandro Agresti 1988 Bombón (DVD) Carlos Sorin 2004 Bonaerense, El Pablo Trapero 2004 Bossa Nova Bruno Barreto 2000 Break of dawn Isaac Artenstein 1990 ISA Feature Film List 1 Institute for the Study of the Americas 17/12/2012 Title Year Format Buena Vista Social Club Wim Wenders 1999 Buena Vista Social Club (DVD) Wim Wenders 1999 -

Half Title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS in CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN

<half title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS</half title> i Traditions in World Cinema General Editors Linda Badley (Middle Tennessee State University) R. Barton Palmer (Clemson University) Founding Editor Steven Jay Schneider (New York University) Titles in the series include: Traditions in World Cinema Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Jay Schneider (eds) Japanese Horror Cinema Jay McRoy (ed.) New Punk Cinema Nicholas Rombes (ed.) African Filmmaking Roy Armes Palestinian Cinema Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi Czech and Slovak Cinema Peter Hames The New Neapolitan Cinema Alex Marlow-Mann American Smart Cinema Claire Perkins The International Film Musical Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad (eds) Italian Neorealist Cinema Torunn Haaland Magic Realist Cinema in East Central Europe Aga Skrodzka Italian Post-Neorealist Cinema Luca Barattoni Spanish Horror Film Antonio Lázaro-Reboll Post-beur Cinema ii Will Higbee New Taiwanese Cinema in Focus Flannery Wilson International Noir Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer (eds) Films on Ice Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport (eds) Nordic Genre Film Tommy Gustafsson and Pietari Kääpä (eds) Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-Bi Adam Bingham Chinese Martial Arts Cinema (2nd edition) Stephen Teo Slow Cinema Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge Expressionism in Cinema Olaf Brill and Gary D. Rhodes (eds) French Language Road Cinema: Borders,Diasporas, Migration and ‘NewEurope’ Michael Gott Transnational Film Remakes Iain Robert Smith and Constantine Verevis Coming-of-age Cinema in New Zealand Alistair Fox New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas Dolores Tierney www.euppublishing.com/series/tiwc iii <title page>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS Dolores Tierney <EUP title page logo> </title page> iv <imprint page> Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. -

Jurado Ópera Prima

INFORMACIÓN 1. Punto de Información SOIFF. HOTELES ESPACIOS DEL CERTAMEN Módulo Tómate un corto. 23. Parador de Turismo de Soria. Plaza Herradores Parque del Castillo, Fortún López, s/n. INFORMACIÓN 2. Centro Cívico Bécquer: Sede 24. Hotel Alda Ciudad de Soria. oficial y oficina de producción. Zaragoza, s/n PRÁCTICA Infantes de Lara, 1. Tel. 975 233 069 25. Art Spa Soria. Navas de Tolosa, 23 OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN en MÓDULO TÓMATE UN CORTO -Ext.2 26. Hotel Leonor. Mirón, s/n. (Plaza Herradores) del 17 al 30 de noviembre. 27. Hotel Apolonia. Puertas de Pro, 5 HORARIO: De 12.00 a 14.00 y de 17.00 a 21.00 horas. SEDES 28. Hotel Castilla. Claustrilla, 5 3. Palacio de la Audiencia. Plaza 29. Hostal Alvi. Alberca, 2 VENTA DE ENTRADAS Mayor, 9 30. Hostal Centro. Plaza Mariano · Para las sesiones en el Palacio de la Audiencia en taquilla una 4. Cines Mercado. Plaza Bernardo Granados, 2 hora antes del inicio de cada sesión. Robles 31. Hostal Solar de Tejada. · Para las sesiones en Cines Mercado en taquilla una hora antes 5. Espacio Alameda. Parque Alameda Claustrilla, 1 del inicio de cada sesión. de Cervantes [La Dehesa] 32. Hostal Viena. García Solier, 1 · Para resto de sesiones y actividades en Oficina de Información 6. Casino Amistad Numancia. 33. Hostal Vitorina. Paseo Florida, 35 del Festival (Plaza Herradores en Módulo Tómate un corto), Collado, 23 hasta dos horas antes del inicio de cada sesión y en la taquilla 7. Conservatorio de Música a la entrada de cada espacio. Oreste Camarca. -

Spanish Videos Use the Find Function to Search This List

Spanish Videos Use the Find function to search this list Velázquez: The Nobleman of Painting 60 minutes, English. A compelling study of the Spanish artist and his relationship with King Philip IV, a patron of the arts who served as Velazquez’ sponsor. LLC Library – Call Number: SP 070 CALL NO. SP 070 Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness. LLC Library CALL NO. Look in German All About My Mother Director: Pedro Almodovar with Cecilia Roth, Penélope Cruz, Marisa Perdes, Candela Peña, Antonia San Juan. 1999, 102 minutes, Spanish with English subtitles. Pedro Almodovar delivers his finest film yet, a poignant masterpiece of unconditional love, survival and redemption. Manuela is the perfect mother. A hard-working nurse, she’s built a comfortable life for herself and her teenage son, an aspiring writer. But when tragedy strikes and her beloved only child is killed in a car accident, her world crumbles. The heartbroken woman learns her son’s final wish was to know of his father – the man she abandoned when she was pregnant 18 years earlier. Returning to Barcelona in search on him, Manuela overcomes her grief and becomes caregiver to a colorful extended family; a pregnant nun, a transvestite prostitute and two troubled actresses. With riveting performances, unforgettable characters and creative plot twists, this touching screwball melodrama is ‘an absolute stunner. -

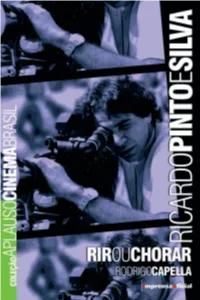

Ricardo Pinto E Silva

Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Ricardo miolo.indd 1 9/10/2007 17:34:34 Ricardo miolo.indd 2 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Rodrigo Capella São Paulo, 2007 Ricardo miolo.indd 3 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Governador José Serra Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Diretor Vice-presidente Paulo Moreira Leite Diretor Industrial Teiji Tomioka Diretor Financeiro Clodoaldo Pelissioni Diretora de Gestão Corporativa Lucia Maria Dal Medico Chefe de Gabinete Vera Lúcia Wey Coleção Aplauso Série Cinema Brasil Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho Coordenador Operacional e Pesquisa Iconográfica Marcelo Pestana Projeto Gráfico Carlos Cirne Editoração Aline Navarro Assistente Operacional Felipe Goulart Tratamento de Imagens José Carlos da Silva Revisão Amancio do Vale Dante Pascoal Corradini Sarvio Nogueira Holanda Ricardo miolo.indd 4 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Apresentação “O que lembro, tenho.” Guimarães Rosa A Coleção Aplauso, concebida pela Imprensa Oficial, tem como atributo principal reabilitar e resgatar a memória da cultura nacional, biogra- fando atores, atrizes e diretores que compõem a cena brasileira nas áreas do cinema, do teatro e da televisão. Essa importante historiografia cênica e audio- visual brasileiras vem sendo reconstituída de manei ra singular. O coordenador de nossa cole- ção, o crítico Rubens Ewald Filho, selecionou, criteriosamente, um conjunto de jornalistas especializados para rea lizar esse trabalho de apro ximação junto a nossos biografados. Em entre vistas e encontros sucessivos foi-se estrei- tan do o contato com todos. Preciosos arquivos de documentos e imagens foram aber tos e, na maioria dos casos, deu-se a conhecer o universo que compõe seus cotidianos. -

Cuban and Russian Film (1960-2000) Hillman, Anna

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Carnivals of Transition: Cuban and Russian Film (1960-2000) Hillman, Anna The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/9733 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] 1 Carnivals of Transition: Cuban and Russian Film (1960-2000) Anna M. Hillman Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Ph.D. degree. Queen Mary, University of London, School of Languages, Linguistics and Film. The candidate confirms that the thesis does not exceed the word limit prescribed by the University of London, and that work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given to research done by others. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on ‘carnivals of transition’, as it examines cinematic representations in relation to socio-political and cultural reforms, including globalization, from 1960 to 2000, in Cuban and Russian films. The comparative approach adopted in this study analyses films with similar aesthetics, paying particular attention to the historical periods and the directors chosen, namely Leonid Gaidai, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, El’dar Riazanov, Juan Carlos Tabío, Iurii Mamin, Daniel Díaz Torres and Fernando Pérez. -

Box-Oldies Por Amor

nn BIEL BIENNE Nummer: Seite: Buntfarbe: Farbe: CyanGelbMagentaSchwarz Gratis in 103 598 Haushalte Distribué gratuitement dans107 000 regelmässige Leser DIE GRÖSSTE ZEITUNG DER 103 598 ménages 107 000 lecteurs fidèles LE PLUS GRAND JOURNAL REGION AUFLAGE: 103 598 DE LA RÉGION ERSCHEINT JEDEN TIRAGE: 103 598 MITTWOCH/DONNERSTAG PARAÎT CHAQUE MERCREDI/JEUDI IN ALLEN HAUSHALTEN BIELS UND DANS TOUS LES MÉNAGES GRENCHENS, DES SEELANDES UND DES DE LA RÉGION BIENNE-JURA BERNOIS- BERNER JURAS. SEELAND-GRANGES. HERAUSGEBER: CORTEPRESS BIEL ÉDITEUR: CORTEPRESS BIENNE 032 327 09 11 / FAX 032 327 09 12 032 327 09 11 / FAX 032 327 09 12 INSERATE: BURGGASSE 14 5. / 6. OKTOBER 2005 WOCHE 40 28. JAHRGANG / NUMMER 40 5 / 6 OCTOBRE 2005 SEMAINE 40 28e ANNÉE / NUMÉRO 40 ANNONCES: RUE DU BOURG 14 032 329 39 39 / FAX 032 329 39 38 032 329 39 39 / FAX 032 329 39 38 INTERNET: http://www.bielbienne.com KIOSKPREIS FR. 1.50 INTERNET: http://www.bielbienne.com Seit Jahren diskutiert und Seeufer: Weg ohne Zukunft? immer noch unsichtbar: der fehlende Seeuferweg entlang des Bielersees lässt die Serpent des rives Bevölkerung in der Innenstadt schmoren. Seite AKTUELL. Le chemin des rives dans la baie de Bienne est un serpent de mer: on en parle beaucoup, mais on ne voit rien venir. Le point avec le directeur des Travaux publics Hubert Box-Oldies Klopfenstein. Page ACTUEL. Die strammen (und harten?) En 1905, le Boxclub de Bienne Männer des Bieler Boxclubs voyait le jour. Il célèbre le cen- stehen im Gründungsjahr tenaire d’une histoire faites de 1905 artig in Reih und Glied succès et de défaites, sans und blicken möglichst düster perdre une once de combati- in die Kamera. -

Amácio Mazzaropi's Filmography

Amácio Mazzaropi’s Filmography Sai da Frente—Get Out of the Way São Paulo, 1952 Cast: Amácio Mazzaropi; Ludy Veloso Leila Parisi, Solange Rivera, Luiz Calderaro, Vicente Leporace, Luiz Linhares, Francisco Arisa, Xandó Batista, Bruno Barabani, Danilo de Oliveira, Renato Consorte, Príncipes da Melodia, Chico Sá, José Renato, o cão Duque (Coronel), Liana Duval, Joe Kantor, Milton Ribeiro, Jordano Martinelli, Izabel Santos, Maria Augusta Costa Leite, Carlo Guglielmi, Labiby Madi, Jaime Pernambuco, Gallileu Garcia, José Renato Pécora, Toni Rabatoni, Ayres Campos, Dalmo de Melo Bordezan, José Scatena, Vittorio Gobbis, Carmen Muller, Rosa Parisi, Annie Berrier, Ovídio ad Martins Melo—acrobats 80 minutes/black and white. Written by Abílio Pereira de Almeida and Tom Payne. Directed by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. Produced by Pio Piccinini/Companhia Cinematográfica Vera Cruz. Opening: 06/25/1952, Cine Marabá and 12 movie theaters. Awards: Prêmio Saci (1952) best supporting actress: Ludy Veloso. Nadando em dinheiro—Swimming in Money São Paulo, 1952 Cast: Amácio Mazzaropi; Ludy Veloso, A. C. Carvalho, Nieta Junqueira, Liana Duval, Carmen Muller, Simone de Moura, Vicente Leporace, Xandó Batista, Francisco Arisa, Jaime Pernambuco, Elísio de Albuquerque, Ayres Campos, Napoleão Sucupira, Domingos Pinho, Nélson Camargo, Bruno Barabani, Jordano Martinelli, o cão Duque (Coronel), Wanda Hamel, Joaquim Mosca, Albino Cordeiro, Labiby Madi, Maria Augusta Costa Leite, Pia Gavassi, Izabel Santos, Carlos Thiré, Annie Berrier, Oscar Rodrigues 152 ● Amácio Mazzaropi’s Filmography de Campos, Edson Borges, Vera Sampaio, Luciano Centofant, Maury F. Viveiros, Antônio Augusto Costa Leite, Francisco Tamura. 90 minutes/ black and white. Written by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. Directed by Abílio Pereira de Almeida.