Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

Spring 2012 Course Guide TABLE of CONTENTS

WOMEN, GENDER, SEXUALITY STUDIES PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Spring 2012 Course Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS This catalog contains descriptions of all Women’s Studies courses for which information was available in our office by the publication deadline for pre-registration. Please note that some changes may have been made in time, and/or syllabus since our print deadline. Exact information on all courses may be obtained by calling the appropriate department or college. Please contact the Five-College Exchange Office (545-5352) for registration for the other schools listed. Listings are arranged in the following order: Options in Women's Studies .................................................................................................................. 1-3 Undergraduate and Graduate Programs explained in detail. Faculty in Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies .................................................................................. 4-5 Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies Core Courses ............................................................................ 6-9 Courses offered through the Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies program Women of Color Courses .................................................................................................................. 10-15 Courses that count towards the Woman of Color requirement for UMass Amherst Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies undergraduate majors and minors. Departmental Courses ..................................................................................................................... -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

Women in Progress and the Power of Patriarchy: a Transnational Comparison Of, Japan, Mexico, and Britain

Copyright By Alyson Lindsey Moss 2019 Women in Progress and the Power of Patriarchy: A Transnational Comparison of, Japan, Mexico, and Britain By Alyson Lindsey Moss A Thesis Submitted to the Department of California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 Committee Members: Dr. Marie Stango Dr. Cliona Murphy Dr. Christopher Tang Women in Progress and the Power of Patriarchy: A Transnational Comparison of Japan, Mexico, and Britain By Alyson Lindsey Moss This thesis has been accepted on behalf of the Department of History by their supervisory committee: C~;tshrist ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project - this tim e consuming, mentally arduous, and three country com parative project - would not have been possible without the support of many wonderful people. If I sound verbose, it is because I have much to say about all those who have helped me write, think, revise, and relax in moments of need. First, to my partner in life and in love, Jeffrey Newby - who read numerous drafts and revisions, and whose own st udying was interrupted with questions from me trying to make sense in my tim es of disorder: thank you, my love. To Dr. Marie Stango, who read each chapter as I finished, and set tim e aside to help me conceptualize terms, comparisons, and context: thank you so much for helping me each step of the way; I could not have continued without your guidance and encour agement. And thank you for challenging m e to do m ore – I have grown so much because of you. -

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema Ekky Imanjaya Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies December 2016 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract Classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced, distributed, and exhibited in the New Order’s Indonesia from 1979 to 1995) are commonly negligible in both national and transnational cinema contexts, in the discourses of film criticism, journalism, and studies. Nonetheless, in the 2000s, there has been a global interest in re-circulating and consuming this kind of films. The films are internationally considered as “cult movies” and celebrated by global fans. This thesis will focus on the cultural traffic of the films, from late 1970s to early 2010s, from Indonesia to other countries. By analyzing the global flows of the films I will argue that despite the marginal status of the films, classic Indonesian exploitation films become the center of a taste battle among a variety of interest groups and agencies. The process will include challenging the official history of Indonesian cinema by investigating the framework of cultural traffic as well as politics of taste, and highlighting the significance of exploitation and B-films, paving the way into some findings that recommend accommodating the movies in serious discourses on cinema, nationally and globally. -

Cine-Excess 13 Delegate Abstracts

Cine-Excess 13 Delegate Abstracts Alice Haylett Bryan From Inside to The Hills Have Eyes: French Horror Directors at Home and Abroad In an interview for the website The Digital Fix, French director Pascal Laugier notes the lack of interest in financing horror films in France. He states that after the international success of his second film Martyrs (2008) he received only one proposition from a French producer, but between 40 and 50 propositions from America: “Making a genre film in France is a kind of emotional roller-coaster” explains Laugier, “sometimes you feel very happy to be underground and trying to do something new and sometimes you feel totally desperate because you feel like you are fighting against everyone else.” This is a situation that many French horror directors have echoed. For all the talk of the new wave of French horror cinema, it is still very hard to find funding for genre films in the country, with the majority of French directors cutting their teeth using independent production companies in France, before moving over to helm mainstream, bigger-budget horrors and thrillers in the USA. This paper will provide a critical overview of the renewal in French horror cinema since the turn of the millennium with regard to this situation, tracing the national and international productions and co-productions of the cycle’s directors as they navigate the divide between indie horror and the mainstream. Drawing on a number of case studies including the success of Alexandre Aja, the infamous Hellraiser remake that never came into fruition, and the recent example of Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge, it will explore the narrative, stylistic and aesthetic choices of these directors across their French and American productions. -

Cinema Nacional E Ensino De Sociologia : Como Trechos De Filme E

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO CURITIBA 2016 ELISANDRA ANGREWSKI CINEMA NACIONAL E ENSINO DE SOCIOLOGIA: COMO TRECHOS DE FILME E FILMES NA ÍNTEGRA PODEM CONTRIBUIR COM A FORMAÇÃO CRÍTICA DO SUJEITO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Educação, no Curso de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Setor de Educação, Linha de Pesquisa Cultura, Escola e Ensino da Universidade Federal do Paraná-UFPR. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Dalla Costa CURITIBA 2016 Dedico este trabalho a todos os profissionais da educação que estiverem na praça Nossa Senhora de Salete (Curitiba) no dia 29 de abril de 2015. RESUMO Estudar o cinema na perspectiva da Sociologia passa, antes de tudo, por uma questão cultural, mas não se limita a isto. Pensar os desdobramentos que cercam a temática do cinema é, também, se deparar com questões de ordem social, política, econômica e ideológica das relações entre indivíduo e sociedade, levando-se em conta que as mesmas são estruturadas a partir das esferas da produção e do consumo. Este conjunto de relações constitui por si mesmo uma problemática das Ciências Sociais. Por isso, quando se trata da sala de aula, a projeção de um filme ou de um trecho de filme, não pode se restringir somente ao lazer ou ao entretenimento. Com a implantação da Lei n° 13.006 de junho de 2014, que torna obrigatória a exibição por 2 horas mensais de filmes nacionais nas escolas, a busca por maneiras de trabalhar o cinema nacional de forma significativa na sala de aula tornou-se premente.Foi a busca pela identificação de diferentes perspectivas de trabalho com cinema nacional no ensino de Sociologia na Educação Básica que motivou esta pesquisa. -

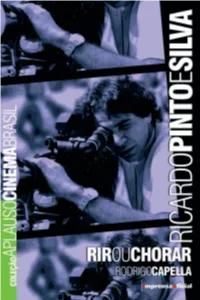

Ricardo Pinto E Silva

Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Ricardo miolo.indd 1 9/10/2007 17:34:34 Ricardo miolo.indd 2 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Ricardo Pinto e Silva Rir ou Chorar Rodrigo Capella São Paulo, 2007 Ricardo miolo.indd 3 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Governador José Serra Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo Diretor-presidente Hubert Alquéres Diretor Vice-presidente Paulo Moreira Leite Diretor Industrial Teiji Tomioka Diretor Financeiro Clodoaldo Pelissioni Diretora de Gestão Corporativa Lucia Maria Dal Medico Chefe de Gabinete Vera Lúcia Wey Coleção Aplauso Série Cinema Brasil Coordenador Geral Rubens Ewald Filho Coordenador Operacional e Pesquisa Iconográfica Marcelo Pestana Projeto Gráfico Carlos Cirne Editoração Aline Navarro Assistente Operacional Felipe Goulart Tratamento de Imagens José Carlos da Silva Revisão Amancio do Vale Dante Pascoal Corradini Sarvio Nogueira Holanda Ricardo miolo.indd 4 9/10/2007 17:34:36 Apresentação “O que lembro, tenho.” Guimarães Rosa A Coleção Aplauso, concebida pela Imprensa Oficial, tem como atributo principal reabilitar e resgatar a memória da cultura nacional, biogra- fando atores, atrizes e diretores que compõem a cena brasileira nas áreas do cinema, do teatro e da televisão. Essa importante historiografia cênica e audio- visual brasileiras vem sendo reconstituída de manei ra singular. O coordenador de nossa cole- ção, o crítico Rubens Ewald Filho, selecionou, criteriosamente, um conjunto de jornalistas especializados para rea lizar esse trabalho de apro ximação junto a nossos biografados. Em entre vistas e encontros sucessivos foi-se estrei- tan do o contato com todos. Preciosos arquivos de documentos e imagens foram aber tos e, na maioria dos casos, deu-se a conhecer o universo que compõe seus cotidianos. -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

The New Woman in Fiction and History: from Literature to Working Woman

Pittsburg State University Pittsburg State University Digital Commons Electronic Thesis Collection 5-2016 THE NEW WOMAN IN FICTION AND HISTORY: FROM LITERATURE TO WORKING WOMAN Vicente Edward Clemons Pittsburg State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Clemons, Vicente Edward, "THE NEW WOMAN IN FICTION AND HISTORY: FROM LITERATURE TO WORKING WOMAN" (2016). Electronic Thesis Collection. 76. https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd/76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW WOMAN IN FICTION AND HISTORY: FROM LITERATURE TOWORKING WOMAN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Vicente Edward Clemons Pittsburg State University Pittsburg, Kansas May, 2016 THE NEW WOMAN IN FICTION AND HISTORY: FROM LITERATURE TO WORKING WOMAN Vicente Edward Clemons APPROVED Thesis Advisor _____________________________________________________ Dr. Michael K. Thompson, History, Philosophy, and Social Sciences Committee Member ___________________________________________________ Dr. Kirstin L. Lawson, History, Philosophy, and Social Sciences Committee Member ___________________________________________________ Dr. Janet S. Zepernick, English and Modern Languages THE NEW WOMAN IN FICTION AND HISTORY: FROM LITERATURE TO WORKING WOMAN An Abstract of the Thesis by Vicente Edward Clemons The purpose of this study was to determine whothe New Woman was, a figure of British feminism at the end of the Victorian Era. The New Woman presented Victorian Britain with an alternative model of womanhood that differed greatly from the ideal Victorian Woman. -

Amácio Mazzaropi's Filmography

Amácio Mazzaropi’s Filmography Sai da Frente—Get Out of the Way São Paulo, 1952 Cast: Amácio Mazzaropi; Ludy Veloso Leila Parisi, Solange Rivera, Luiz Calderaro, Vicente Leporace, Luiz Linhares, Francisco Arisa, Xandó Batista, Bruno Barabani, Danilo de Oliveira, Renato Consorte, Príncipes da Melodia, Chico Sá, José Renato, o cão Duque (Coronel), Liana Duval, Joe Kantor, Milton Ribeiro, Jordano Martinelli, Izabel Santos, Maria Augusta Costa Leite, Carlo Guglielmi, Labiby Madi, Jaime Pernambuco, Gallileu Garcia, José Renato Pécora, Toni Rabatoni, Ayres Campos, Dalmo de Melo Bordezan, José Scatena, Vittorio Gobbis, Carmen Muller, Rosa Parisi, Annie Berrier, Ovídio ad Martins Melo—acrobats 80 minutes/black and white. Written by Abílio Pereira de Almeida and Tom Payne. Directed by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. Produced by Pio Piccinini/Companhia Cinematográfica Vera Cruz. Opening: 06/25/1952, Cine Marabá and 12 movie theaters. Awards: Prêmio Saci (1952) best supporting actress: Ludy Veloso. Nadando em dinheiro—Swimming in Money São Paulo, 1952 Cast: Amácio Mazzaropi; Ludy Veloso, A. C. Carvalho, Nieta Junqueira, Liana Duval, Carmen Muller, Simone de Moura, Vicente Leporace, Xandó Batista, Francisco Arisa, Jaime Pernambuco, Elísio de Albuquerque, Ayres Campos, Napoleão Sucupira, Domingos Pinho, Nélson Camargo, Bruno Barabani, Jordano Martinelli, o cão Duque (Coronel), Wanda Hamel, Joaquim Mosca, Albino Cordeiro, Labiby Madi, Maria Augusta Costa Leite, Pia Gavassi, Izabel Santos, Carlos Thiré, Annie Berrier, Oscar Rodrigues 152 ● Amácio Mazzaropi’s Filmography de Campos, Edson Borges, Vera Sampaio, Luciano Centofant, Maury F. Viveiros, Antônio Augusto Costa Leite, Francisco Tamura. 90 minutes/ black and white. Written by Abílio Pereira de Almeida. Directed by Abílio Pereira de Almeida.